1.

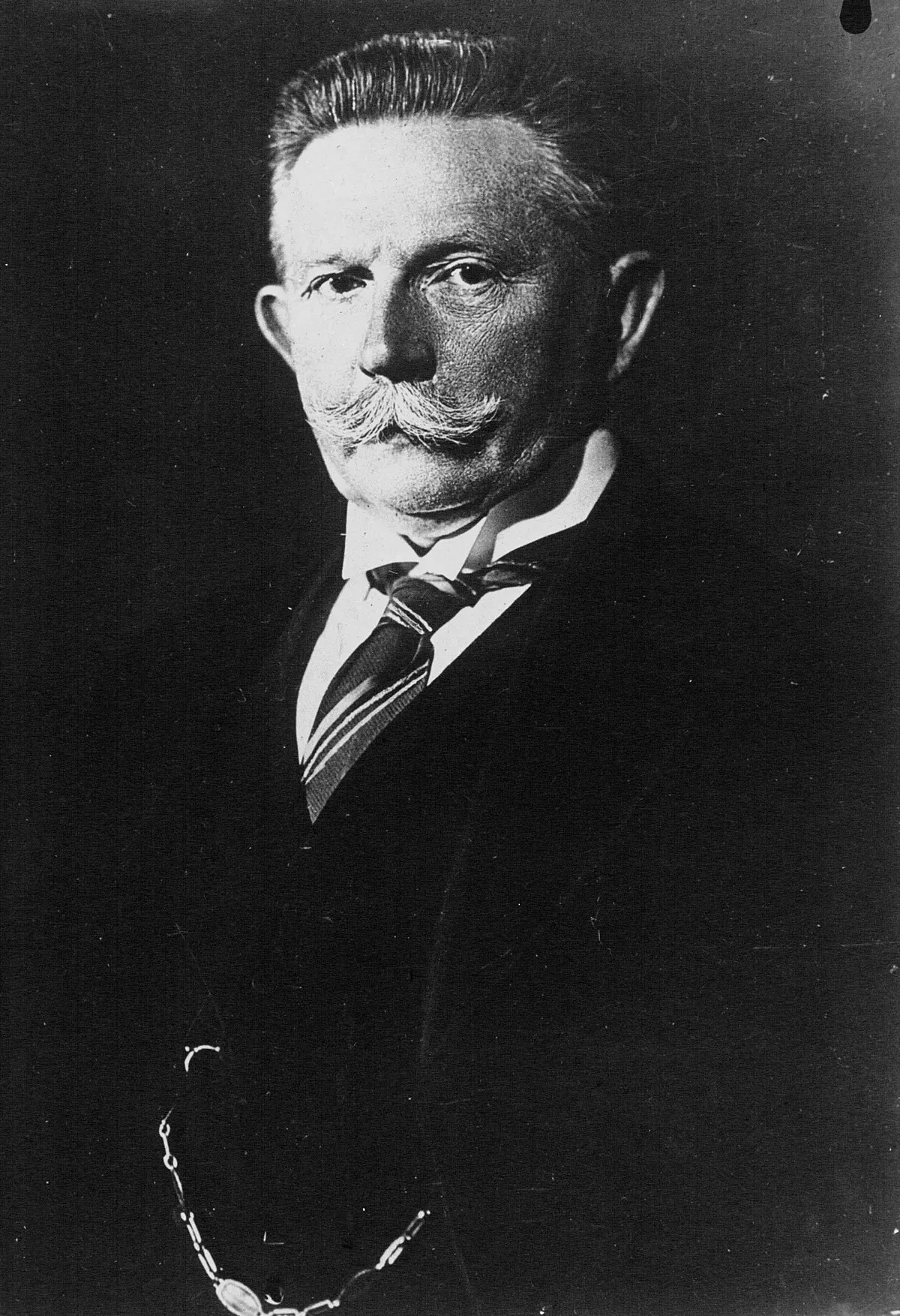

1. Alfred Ernst Christian Alexander Hugenberg was an influential German businessman and politician.

1.

1. Alfred Ernst Christian Alexander Hugenberg was an influential German businessman and politician.

An important figure in nationalist politics in Germany during the first three decades of the twentieth century, Hugenberg became the country's leading media proprietor during the 1920s.

The plan failed, and by the end of 1933 Alfred Hugenberg had been pushed to the sidelines.

Alfred Hugenberg believed in social Darwinism, despised communism, socialism and trade unions, and was in general skeptical of big business and finance.

Alfred Hugenberg worked in the Prussian civil service and in private business before joining the Krupp steel works where he was chairman of the board of directors from 1909 until 1918.

Alfred Hugenberg blamed Germany's defeat on Jews and socialists who had supposedly stabbed the German army in the back.

Alfred Hugenberg became chairman of the DNVP after the party's substantial losses in the 1928 Reichstag elections.

Alfred Hugenberg obtained "dictatorial" leadership powers and tried to transform the party into a "Hugenberg movement".

Alfred Hugenberg shifted emphasis to the extra-parliamentary sphere with the aim of forcing the replacement of parliamentary government by an authoritarian regime.

Alfred Hugenberg's radicalism caused the DNVP to split, with many key industrialists leaving the party.

Alfred Hugenberg nevertheless became minister of Economics and of Food and Agriculture in the Hitler cabinet.

Alfred Hugenberg became increasingly isolated in the cabinet and failed in his attempt to become "economic dictator".

Alfred Hugenberg was forced out of the cabinet after five months, on the same day that the DNVP voted to disband.

In 1891, Alfred Hugenberg was awarded a PhD at Strassburg for his dissertation Internal Colonization in Northwest Germany, in which he set out three ideas that guided his political thought for the rest of his life:.

Later in 1891, Alfred Hugenberg co-founded, along with Karl Peters, the ultra-nationalist General German League, and in 1894 its successor movement, the Pan-German League.

From 1894 to 1899, Alfred Hugenberg worked as a Prussian civil servant in Posen.

The son of an upper-middle-class family, Alfred Hugenberg initially resented the, but over time he came to accept the idea of "feudal-industrial control of Germany", believing in an alliance of and industrialists.

Alongside these beliefs, Alfred Hugenberg maintained an ardent belief in imperialism and opposition to democracy and socialism.

Alfred Hugenberg was strongly anti-Polish, and criticized the Prussian government for its "inadequate" Polish policies, favoring a more vigorous policy of Germanization.

Alfred Hugenberg initially took a role organizing agricultural societies before entering the civil service in the Prussian Ministry of Finance in 1903.

Alfred Hugenberg came into conflict with his superiors, who opposed his plans to confiscate all the non-productive estates of the in order to settle hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans who would become his idealized farmer-small businessmen and "Germanize" the East.

Alfred Hugenberg subsequently left the public sector to pursue a career in business, and in 1909 he was appointed chairman of the supervisory board of Krupp Steel where he built up a close personal and political relationship with Baron Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, the CEO of Krupp AG.

Alfred Hugenberg killed himself or died from illness shortly after the Social Democratic newspaper Vorwarts published love letters he had written to his Italian male lovers.

Alfred Hugenberg did not approve of either union and instead sponsored a "yellow" union representing the management, making his tenure a time of endless disputes with the workers.

Alfred Hugenberg's strong social Darwinist views led him to argue that the problem of poverty was a genetic problem, with the poor inheriting bad genes that made them unsuccessful in life.

At the ceremony, Alfred Hugenberg praised the Emperor in his acceptance speech and went on to say that democracy would not improve the condition of the German working class, but only a "very much richer, very much greater and very much more powerful Germany" would solve its problems.

Alfred Hugenberg believed that center-right and right-wing parties such as the National Liberals and the Conservatives needed more newspapers to champion their views.

In 1914, Alfred Hugenberg welcomed the onset of the First World War and resumed his work with his close friend Heinrich Class of the Pan-German League.

In 1915, Alfred Hugenberg published a telegram to Class in the name of the united chambers of commerce of the Ruhr, demanding that Wilhelm II dismiss Bethmann Hollweg and if the emperor was unwilling, that the military should depose Bethmann Hollweg, stating that if the Reich failed to achieve the annexationist platform once the war was won, it would cause a revolution from the right that would end the monarchy.

Alfred Hugenberg was secretly assisted by the state in his efforts to build a media empire, all the more so as the state distrusted the liberal newspapers owned by the Ullstein brothers and by Rudolf Mosse, all of whom were Jewish, leading the state to request that a circle of "patriotic" businessmen lend Alfred Hugenberg the necessary funds to buy up newspapers.

In buying the Scherl corporation, Alfred Hugenberg acquired the Berlin newspaper, which became the flagship paper of his media empire.

Alfred Hugenberg exploited the corporate law, which he knew so well, and used his own financial acumen, which had been so finely developed, to secure his empire.

Alfred Hugenberg knew the rules of the game and manipulated them to full advantage.

Alfred Hugenberg remained at Krupp until 1918, when he set out to build his own business, and during the Great Depression he was able to buy up dozens of local newspapers.

Alfred Hugenberg's increasing involvement in Pan-German and annexationist causes together with his interest in building a media empire caused him to depart from Krupp, which he found to be a distraction from what really interested him.

Alfred Hugenberg was always convinced that Germany would recover from the defeat of 1918, all the more so as he believed the German military had not actually been defeated in 1918.

Alfred Hugenberg was one of a number of Pan-Germans to become involved in the National Liberal Party in the runup to the First World War.

In 1919 Alfred Hugenberg followed most of the Fatherland Party into the German National People's Party, which he represented in the Weimar National Assembly, which wrote the 1919 Constitution of the Weimar Republic.

Unable to find positive goals that were capable of holding the DNVP together, let alone of creating the sort of national unity that he wanted, Alfred Hugenberg came to define his in negative terms by seeking to find "enemies" to provide a unity in hatred.

In 1920, Alfred Hugenberg founded a populist tabloid, the, which became his most profitable newspaper, having a daily circulation of 216,000 by 1929.

Alfred Hugenberg had founded the TU to compete with the Telegraph Bureau following complaints from German conservatives of "liberal bias" at the Wolff-owned Telegraph Bureau.

Alfred Hugenberg founded a thinktank, the to promote his ideas, while he lived a pseudo-aristocratic lifestyle at his estate at Rohbraken.

In 1922, together with the industrialist Emil Kirdorf, Alfred Hugenberg created an investment fund known as that served to subsidize groups "very effective politically, but not commercially profitable".

Alfred Hugenberg emerged as one of the leaders of the latter faction that wanted to reject the Dawes Plan, writing bitterly at the time that "two-thirds of the German people including those behind the German National People's Party are internally prepared to let the freedom, honor and future of their land be sold in exchange for a few pieces of silver".

In January 1926, Alfred Hugenberg was involved in a plan for a putsch organized by his good friend, Henrich Class, calling for President Hindenburg to appoint as chancellor someone who was unacceptable for the, which would lead to a motion of no confidence.

Class planned to have Alfred Hugenberg serve as minister of finance in the new government.

The fact that Alfred Hugenberg rarely spoke in public during this period aided their efforts, giving him an aura of mystery.

In March 1927, Alfred Hugenberg purchased UFA, Europe's largest film studio, which brought him further attention.

Alfred Hugenberg presented the purchase of UFA as a political move instead of a business move.

Alfred Hugenberg moved the party in a far more radical direction than it had taken under its previous leader, Kuno Graf von Westarp.

Alfred Hugenberg was the leader of the DNVP monarchist purists for whom no changes in the party's platform were acceptable, and he started to press for the DNVP to expel Lambach as a way of bringing down Westarp, who only agreed to censure Lambach for his article.

However, the Lambach case had galvanized the DNVP's membership against Westarp and for Alfred Hugenberg, who knew that the DNVP would be calling a party congress later that year that would have the power to elect a new leader, and that the Lambach affair was a godsend.

The fact that the members of the Pan-German League were overrepresented at the party congress further favored Alfred Hugenberg, who was elected the DNVP's new leader on 21 October 1928.

Alfred Hugenberg gave the impression that the DNVP would not need any more donations from big business as he was so wealthy that he would fund the DNVP entirely out of his own pocket.

Alfred Hugenberg sought to eliminate internal party democracy and instill a within the DNVP, leading to some members breaking away to establish the Conservative People's Party in late 1929.

Alfred Hugenberg's unwillingness to have the DNVP enter the Bruning cabinet greatly embittered the industrialists, who complained that the DNVP under his leadership was a perpetual opposition party, and as a result the largest contributor to the DNVP by 1931 had become Alfred Hugenberg himself, which had the effect of cementing his control.

Alfred Hugenberg believed in the politics of polarization under which German politics were to be divided into two blocs, the right-wing "national" bloc whose leader he envisioned as himself and the Marxist left consisting of the Social Democrats and the Communists.

Alfred Hugenberg initially intended as his wedge issue the subject of constitutional reform, but he dropped it in the spring of 1929 as "too abstract" for most people in favor of opposing the Young Plan for reparations.

At the time, Alfred Hugenberg's critics pointed out that if the Young Plan was rejected, then the French occupation of the Rhineland would continue until the summer of 1935, an aspect of Alfred Hugenberg's rejectionist strategy that he never dwelled on.

Alfred Hugenberg was vehemently opposed to the Young Plan, and he set up a "Reich Committee for the German People's Petition" to oppose it, featuring the likes of Franz Seldte, Heinrich Class, Theodor Duesterberg and Fritz Thyssen.

On 9 July 1929, Alfred Hugenberg founded the Reich Committee on the German Initiative to campaign against the Young Plan, which the Alfred Hugenberg newspapers hailed as the most important political development.

Alfred Hugenberg saw the referendum as the beginning of the counterrevolution, writing at the time that thanks to him "a front has arisen that knows only one goal: how the revolution [of 1918] can be overcome and a nation of free men can again be made from Germans".

Adolf Hitler was the only realistic candidate, and Alfred Hugenberg decided that he would use the Nazi Party leader to get his way.

The Alfred Hugenberg newspapers went all-out in support of the "Freedom Law", running glaring headlines in support, but when the referendum was held, only 5,538,000 Germans voted yes for the "Freedom Law", which was insufficient to for the law to pass.

Hitler was able to use Alfred Hugenberg to push himself into the political mainstream, and once the Young Plan was passed by the Reichstag, Hitler promptly ended his links with Alfred Hugenberg.

On 6 January 1930, Alfred Hugenberg was summoned to meet President Paul von Hindenburg, who told him that now the Young Plan had been passed, he had no more need for Muller, and he was planning to bring in a new presidential government very soon that would be "anti-parliamentary and anti-Marxist".

Much to Hindenburg's vexation, Alfred Hugenberg refused to take part, maintaining that he would not be a cabinet minister in a government that paid reparations.

The promise of more aid to farmers was popular in rural areas, and several DNVP representatives led by Westarp wanted the party to vote for the bill, which Alfred Hugenberg was opposed to on the grounds that some of the tax revenue raised would go to France in the form of reparations.

That Alfred Hugenberg was incapable of controlling his own delegation led Hitler to openly mock him as a weak leader.

Alfred Hugenberg came across as awkward, arrogant and above all very dull.

On 10 February 1931 Alfred Hugenberg joined the Nazi Party in walking with the DNVP out of the Reichstag altogether as a protest against the Bruning government.

However, Alfred Hugenberg's hubristic arrogance enraged Hindenburg, who complained that he was a, a field marshal and the president while Alfred Hugenberg treated him "like a schoolboy".

The fact that DNVP members did not have to pay dues, as NSDAP members did, proved to be a weakness, as the requirement to pay monthly dues inspired Nazi Party members with far more devotion to their cause than the DNVP members, who blithely assumed that Alfred Hugenberg's fortune was more than enough to handle the party's financial needs.

On 9 July 1931, Alfred Hugenberg released a joint statement with Hitler guaranteeing that the pair would cooperate for the overthrow of the Weimar "system".

Alfred Hugenberg wanted to announce the creation of his front in Bad Harzburg in Braunschweig, a governed by a DNVP-NSDAP coalition, to symbolize unity on the right.

Hitler was wary of the plans, leading Alfred Hugenberg to complain in private of his "megalomania, but of uncontrollability, imprudence and lack of judgement".

At the party congress, Alfred Hugenberg blamed the Great Depression on the Treaty of Versailles, the gold standard and a misplaced belief in "international capital".

Ultimately, Alfred Hugenberg argued that the solution to the Great Depression was imperialism as he argued that Germans were a "", which he felt was the fundamental problem with the German economy.

Indeed, the rift between the two opened further when Alfred Hugenberg, fearing that Hitler might win the presidency, persuaded Theodor Duesterberg to run as a Junker candidate after Prince Oskar of Prussia declined to run as the DNVP candidate.

In desperation, Alfred Hugenberg tried to get Crown Prince Wilhelm to run as the DNVP's candidate, only for the exiled emperor to issue a statement saying it was "absolute idiocy" for his son to run for president.

Alfred Hugenberg's speeches were intensely boring, and his attempt to create a Hitler-style personality cult around himself failed.

Alfred Hugenberg's rotund build and short stature together with his handlebar mustache, brush-cut hairstyle and the Wilhelmine way of dressing with a high collar made him resemble a hamster, giving him a nickname that he hated; more broadly, the nickname suggested that he was not being taken as seriously as he would have liked.

Together with the German People's Party, the DNVP was the only party in the that supported the new government led by Franz von Papen, and though three ministers in the new cabinet were DNVP members, Alfred Hugenberg himself was excluded.

The possibility of an alliance between the Nazis and the Centre without the DNVP, which was openly discussed, led Alfred Hugenberg to condemn Hitler for using parliamentary methods.

At Papen's request, Hindenburg dissolved the for new elections rather than allowing another government to be formed, and in the ensuing election campaign, Alfred Hugenberg took a strongly anti-Nazi line, portraying Hitler as irresponsible and dangerous.

Alfred Hugenberg's party had experienced a growth in support in the November 1932 election at the expense of the Nazis.

Alfred Hugenberg hoped to harness the Nazis for his own ends , and as such he dropped his attacks on them for the campaign for the March 1933 election.

When Schleicher refused to exclude Stegerwald from his plans, Alfred Hugenberg broke off negotiations.

Hitler did agree in principle to allow Schleicher to serve under him as Defense minister, although Alfred Hugenberg warned the Nazi leader that as long as Paul von Hindenburg was president, Hitler would never be chancellor.

On 27 January 1933, Alfred Hugenberg met with Hitler when he was informed Papen was now supporting a cabinet with Hitler as chancellor and Papen as vice-chancellor.

Papen's assurances that Hitler would be "boxed in" since the majority of the cabinet would not be Nazis, coupled with the chance to be "economic dictator" led Alfred Hugenberg to accept Hitler as chancellor and join the new government.

Alfred Hugenberg agreed to join the Hitler government with the understanding that there would be no new elections, and upon waiting to be sworn in by President Hindenburg, he first learned that Hitler was planning to call new elections, precipitating a lengthy shouting match with Hitler.

Alfred Hugenberg, who served jointly as the and Prussian ministers of economics and agriculture, and boasted of his plans to be "economic dictator", was widely seen as the dominant minister in the new government.

Alfred Hugenberg named Paul Bang, the economic expert of the Pan-German League, as the state secretary in the Economics ministry.

The man whom Alfred Hugenberg named as state secretary in the Agriculture ministry, Hans-Joachim von Rohr, proved more interested in his portfolio, but in common with many other people found Alfred Hugenberg a difficult man to work with.

Alfred Hugenberg made no effort to stop Hitler's ambition of becoming a dictator; he himself was authoritarian by inclination.

Alfred Hugenberg used his control of UFA in the election, having UFA cinemas show newsreels that emphasized his role in the new government.

Alfred Hugenberg was quietly concerned what Hitler might do if the passed the Enabling Act, and tried to include some amendments intended to limit Hitler's power, only to be undercut by Hindenburg and by calls from within his own party to merge with the Nazi party.

Nevertheless, Alfred Hugenberg was Minister of the Economy in the new government and was appointed Minister of Agriculture in the Nazi cabinet, largely due to the support his party enjoyed amongst the north German landowners.

Alfred Hugenberg fancied himself the "economic dictator", but at cabinet meetings the other conservative ministers such as Papen, Foreign Minister Baron Konstantin von Neurath and Defense Minister General Werner von Blomberg all objected to Alfred Hugenberg's plans for an autarkic economy as unworkable and likely to isolate Germany internationally.

On 17 May 1933, Alfred Hugenberg met with Hindenburg to complain that the Nazis forced some civil servants who were DNVP members out of their jobs or alternatively forced them to join the NSDAP.

Hindenburg conceded that some of the Nazis were acting illegally, but told Alfred Hugenberg that he would take no action because this was a "critical time" and one must remember "what a national upsurge the new movement has brought us".

Meanwhile, in June 1933, Hitler was forced to disavow the plan Alfred Hugenberg proposed while attending the London World Economic Conference, that a program of German colonial expansion in both Africa and Eastern Europe was the best way of ending the Great Depression, which created a major storm abroad.

Alfred Hugenberg argued in a speech given in London on 16 June 1933 that Germany needed the return of all its former colonies in Africa in order to "open up for a areas which could provide space for the settlement of its vigorous race and construct great works of peace".

Rather than accept the rebuke, Alfred Hugenberg chose to issue a statement claiming he was speaking on behalf of the German government, an action that made the German delegation appear to be "ridiculous", as Neurath complained at a subsequent cabinet meeting.

Neurath told the cabinet that "a single member cannot simply overlook the objections of the others" and that Alfred Hugenberg "either did not understand these objections, which were naturally clothed in polite form, or he did not want to understand them".

The fact that Alfred Hugenberg chose to engage in a vendetta with Neurath over the conflicting press releases issued in London instead of dropping the matter as Neurath had urged him to do, made him appear very petty and spiteful and cost him whatever sympathy he might had enjoyed from the other conservative cabinet ministers.

Alfred Hugenberg's fate was sealed when the Prussian State Secretary Fritz Reinhardt, ostensibly a subordinate to Alfred Hugenberg as Minister of Economy, presented a work-creation plan to the cabinet.

An increasingly isolated figure, Alfred Hugenberg was finally forced to resign from the cabinet after a whisper campaign against him to remove him from power.

Alfred Hugenberg announced his formal resignation on 29 June 1933, and he was replaced by others who were loyal to the Nazi Party, Kurt Schmitt in the Economics Ministry and Richard Walther Darre in the Agriculture Ministry.

Alfred Hugenberg signed a written agreement to dissolve the DNF in return for which Hitler promised that civil servants who were DNF members would be recognized as "full and legally equal co-fighters" and to release those party members in jail.

However, his stock with the Nazis had fallen so much that in December 1933 the Telegraph Union, the news agency owned by Alfred Hugenberg, was de facto taken over by the Propaganda Ministry and merged into a new German News Office.

Alfred Hugenberg was allowed to remain in the Reichstag until 1945 as one of 22 so-called "guest" members who were officially designated as non-party representatives.

Alfred Hugenberg did not let them go cheaply as he negotiated a large portfolio of shares in the Rhenish-Westphalian industries in return for his cooperation.

Alfred Hugenberg last saw Hitler in February 1935, when he presented a plan to replace rental housing with condominiums, which went nowhere.

Alfred Hugenberg's son was killed in action on the Eastern Front; characteristically he refused to express any grief in public lest he be accused of weakness.

Alfred Hugenberg was arrested by British military police on 28 September 1946, and his remaining assets were frozen.

Alfred Hugenberg was initially detained after the war, but in 1949 a Denazification court at Detmold adjudged him a "Mitlaufer" rather than a Nazi, meaning that he was allowed to keep his property and business interests.

Alfred Hugenberg died in Kukenbruch near Detmold on 12 March 1951, having only the company of a nurse, as he wished his family not to see him in his death throes.