1.

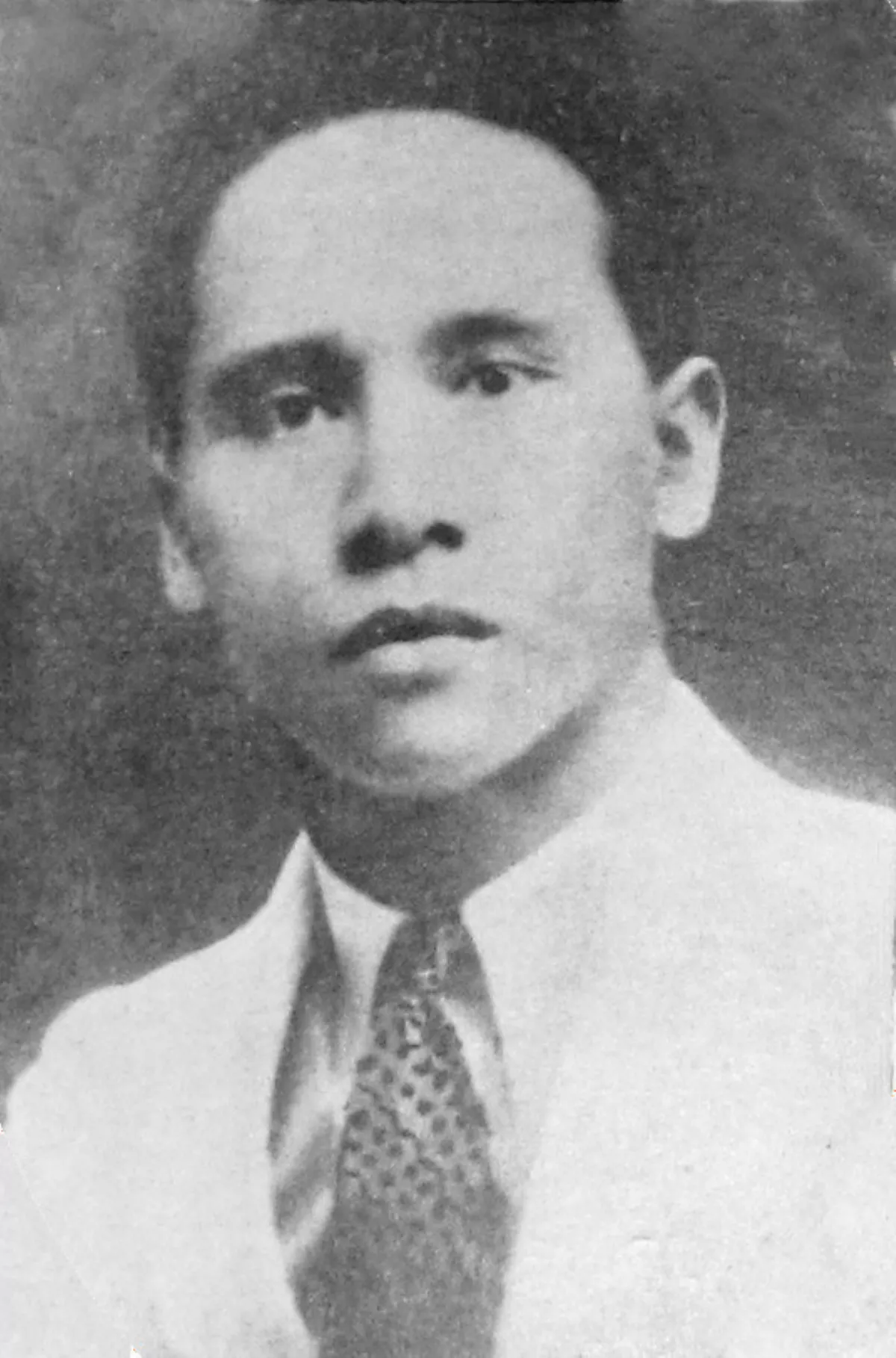

1. Tengku Amir Hamzah was an Indonesian poet and National Hero of Indonesia.

1.

1. Tengku Amir Hamzah was an Indonesian poet and National Hero of Indonesia.

Amir Hamzah began writing poetry while still a teenager: though his works are undated, the earliest are thought to have been written when he first travelled to Java.

Amir Hamzah's diction, using both Malay and Javanese words and expanding on traditional structures, was influenced by the need for rhythm and metre, as well as symbolism related to particular terms.

Amir Hamzah has been called the "King of the Poedjangga Baroe-era Poets" and the only international-class Indonesian poet from before the Indonesian National Revolution.

The date officially recognised by the Indonesian government is 28 February 1911, a date Amir Hamzah used throughout his life.

Amir Hamzah was schooled in Islamic principles such as Qu'ran reading, fiqh, and tawhid, and studied at the Azizi Mosque in Tanjung Pura from a young age.

At the Dutch-language elementary school where Amir Hamzah first studied, he began writing and received good marks; in her biography of him, Nh.

Dini writes that Amir Hamzah was nicknamed "older brother" by his classmates as he was much taller than them.

In 1924 or 1925, Amir Hamzah graduated from the school in Langkat and moved to Medan to study at the Meer Uitgebreid Lager Onderwijs there.

Alone aboard the Plancus, Amir Hamzah made the three-day boat trip to Java.

Also in Batavia, Amir Hamzah became involved with the social organisation Jong Sumatera.

Amir Hamzah would meet with fellow Sumatrans and discuss the social plight of the Malay archipelago's populace under Dutch colonial rule.

In 1930 Amir Hamzah became head of the Surakartan branch of the Indonesia Muda, delivering a speech at the 1930 Youth Congress and serving as an editor of the organisation's magazine Garuda Merapi.

Amir Hamzah's mother died in 1931, and his father the year after, meaning that his education could no longer be funded.

In 1932 Amir Hamzah was able to return to Batavia and begin his legal studies, taking up a part-time job as a teacher.

Around September 1932 Armijn Pane, upon the urgings of Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana, editor of "Memadjoekan Sastera", invited Amir Hamzah to help them establish an independent literary magazine.

Amir Hamzah accepted, and was tasked with writing letters to solicit submissions; a total of fifty letters were sent to noted writers, including forty sent to contributors to "Memadjoekan Sastera".

The new magazine was left under the editorial control of Armijn and Alisjahbana, while Amir Hamzah published almost all of his subsequent writings there.

In mid-1933 Amir Hamzah was recalled to Langkat, where the Sultan informed him of two conditions which he had to fulfil to continue his studies: be a diligent student and abandon the independence movement.

Amir Hamzah continued to publish in Poedjangga Baroe, including a series of five articles on Eastern literatures from June to December 1934 and a translation of the Bhagavad Gita from 1933 to 1935.

Now a prince, Amir Hamzah was given the title Tengku Pangeran Indra Putera.

Amir Hamzah was held as a prisoner of war until 1943, when influence from the Sultan allowed him to be released.

In early 1946, rumours spread in Langkat that Amir Hamzah had been seen dining with representatives of the returning Dutch government, and there was growing unrest within the general populace.

On 7 March 1946, during a social revolution led by factions of the Communist Party of Indonesia, a group staunchly against feudalism and the nobility, Amir Hamzah's power was stripped from him and he was arrested; Kamiliah and Tahura escaped.

In 1948 the grave at Kuala Begumit was dug up and the remains identified by family members; Amir Hamzah's bones were identified owing to a missing false tooth.

Amir Hamzah was raised in a court setting, where he spoke Malay until it had "become his flesh and blood".

Amir Hamzah would listen to these when they were read in public ceremonies, and as an adult he kept a large collection of such texts, though these were destroyed during the communist revolution.

The literary critic Muhammad Balfas writes that, unlike his contemporaries, Amir Hamzah drew little influence from sonnets and the neo-romantic Dutch poets, the Tachtigers; Johns comes to the same conclusion.

The Australian literary scholar Keith Foulcher noting that the poet quoted Willem Kloos's "Lenteavond" in his article on pantuns, suggests that Amir Hamzah was very likely influenced by the Tachtigers.

Jassin and the poet Arief Bagus Prasetyo, among others, argue that Amir Hamzah was a purely orthodox Muslim and that it showed in his work.

Johns writes that, though he was not a mystic, Amir Hamzah was not a purely devotional writer, instead promoting a form of "Islamic Humanism".

Amir Hamzah writes that the concept of a jealous God is not found in Islam, but is in the Bible, citing Exodus 20:5 and Exodus 34:14.

Jassin writes that Amir Hamzah's poems were influenced by his love for one or more women, in Buah Rindu referred to as "Tedja" and "Sendari-Dewi"; he opines that the woman or women are never named as Amir Hamzah's love for them is the key.

Altogether Amir Hamzah wrote fifty poems, eighteen pieces of lyrical prose, twelve articles, four short stories, three poetry collections, and one original book.

Amir Hamzah translated forty-four poems, one piece of lyrical prose, and one book; these translations, Johns writes, generally reflected themes important in his original work.

The vast majority of Amir Hamzah's writings were published in Poedjangga Baroe, although some earlier ones were published in Timboel and Pandji Poestaka.

Johns writes that the poems in the collections appear to be arranged in chronological order; he points to the various degrees of maturity Amir Hamzah showed as his writing developed.

Jassin writes that Amir Hamzah maintained a Malay identity throughout his works, despite attending schools run by Europeans.

Mihardja notes that Amir Hamzah wrote his works at a time when all of their classmates, and many poets elsewhere, were "pouring their hearts or thoughts" in Dutch, or, if "able to free themselves from the shackles of Dutch", in a local language.

Teeuw summarises that Amir Hamzah recognises that he would not exist if God did not.

Johns suggests that ultimately Amir Hamzah finds little solace in God, as he "did not possess the transcendent faith which can make a great sacrifice, and resolutely accept the consequences"; instead, he seems to regret his choice to go to Sumatra and then revolts against God.

Amir Hamzah's diction was influenced by the need for rhythm and metre, as well as symbolism related to particular terms.

Amir Hamzah borrows heavily from other Indonesian languages, particularly Javanese and Sundanese; the influences are more predominant in Nyanyi Sunyi.

Amir Hamzah has received extensive recognition from the Indonesian government, beginning with recognition from the government of North Sumatra soon after his death.

Several streets are named after Amir Hamzah, including in Medan, Mataram, and Surabaya.

Anwar wrote that the poet was the "summit of the Pudjangga Baru movement", considering Nyanyi Sunyi to have been a "bright light he [Amir Hamzah] shone on the new language"; however, Anwar disliked Buah Rindu, considering it too classical.

Amir Hamzah was not a leader with a loud voice driving the people, either in his poems or his prose.

Amir Hamzah was a man of emotion, a man of awe, his soul easily shaken by the beauty of nature, sadness and joy alternating freely.

Amir Hamzah longed unendingly, in the most dark of days, for joy, for 'life with a definite purpose'.