1.

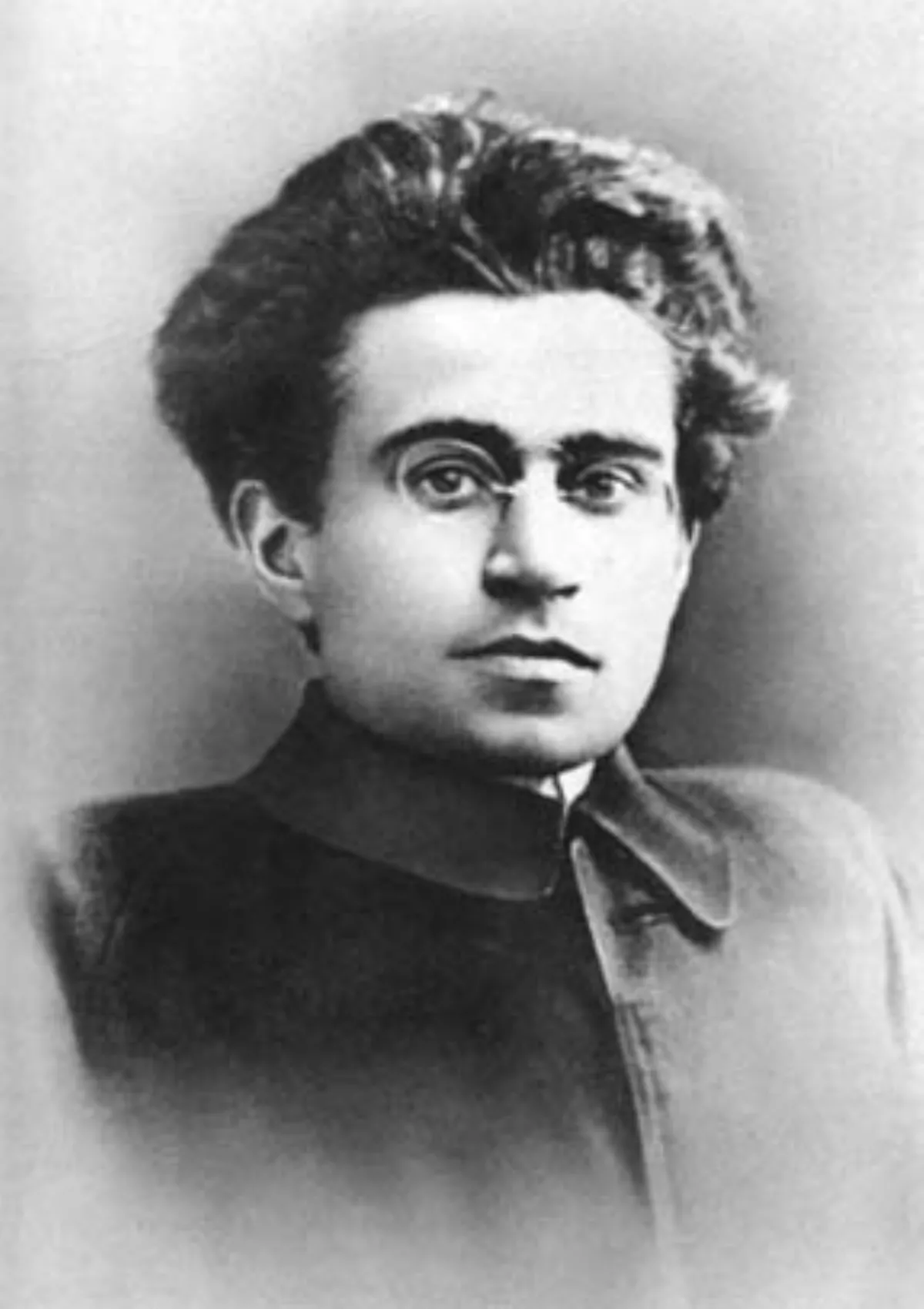

1. Antonio Francesco Gramsci was an Italian Marxist philosopher, linguist, journalist, writer, and politician.

1.

1. Antonio Francesco Gramsci was an Italian Marxist philosopher, linguist, journalist, writer, and politician.

Antonio Gramsci wrote on philosophy, political theory, sociology, history, and linguistics.

Antonio Gramsci was a founding member and one-time leader of the Italian Communist Party.

Antonio Gramsci attempted to break from the economic determinism of orthodox Marxist thought, and so is sometimes described as a neo-Marxist.

Antonio Gramsci held a humanistic understanding of Marxism, seeing it as a philosophy of praxis and an absolute historicism that transcends traditional materialism and traditional idealism.

Antonio Gramsci was born in Ales, in the province of Oristano, on the island of Sardinia, the fourth of seven sons of Francesco Antonio Gramsci and Giuseppina Marcias.

Francesco Antonio Gramsci was born in the small town of Gaeta, in the province of Latina, Lazio, to a well-off family from the southern Italian regions of Campania and Calabria and of Arbereshe descent.

Antonio Gramsci himself believed that his father's family had left Albania as recently as 1821.

Antonio Gramsci's mother belonged to a Sardinian landowning family from Sorgono, in the province of Nuoro.

Francesco Antonio Gramsci worked as a low-level official, and his financial difficulties and troubles with the police forced the family to move about through several villages in Sardinia until they finally settled in Ghilarza.

In 1898, Antonio Gramsci's father was convicted of embezzlement and imprisoned, reducing his family to destitution.

The young Antonio Gramsci had to abandon schooling and work at various casual jobs until his father's release in 1904.

Antonio Gramsci was plagued by various internal disorders throughout his life.

Antonio Gramsci started secondary school in Santu Lussurgiu and completed it in Cagliari, where he lodged with his elder brother Gennaro, a former soldier whose time on the mainland had made him a militant socialist.

At the time, Antonio Gramsci's sympathies did not yet lie with socialism but rather with Sardinian autonomism, as well as the grievances of impoverished Sardinian peasants and miners, whose mistreatment by the mainlanders would later deeply contribute to his intellectual growth.

In 1911, Antonio Gramsci won a scholarship to study at the University of Turin, sitting the exam at the same time as Palmiro Togliatti.

Antonio Gramsci was in Turin while it was going through industrialization, with the Fiat and Lancia factories recruiting workers from poorer regions.

Antonio Gramsci frequented socialist circles as well as associating with Sardinian emigrants on the Italian mainland.

Antonio Gramsci joined the Italian Socialist Party in late 1913, where he would later occupy a key position and observe from Turin the Russian Revolution.

An articulate and prolific writer of political theory, Antonio Gramsci proved a formidable commentator, writing on all aspects of Turin's social and political events.

Antonio Gramsci was at this time involved in the education and organisation of Turin workers; he spoke in public for the first time in 1916 and gave talks on topics such as Romain Rolland, the French Revolution, the Paris Commune, and the emancipation of women.

In opposition to Bordiga, Antonio Gramsci supported the Arditi del Popolo, a militant anti-fascist group which struggled against the Blackshirts.

Antonio Gramsci would be a leader of the party from its inception but was subordinate to Bordiga, whose emphasis on discipline, centralism and purity of principles dominated the party's programme until the latter lost the leadership in 1924.

In 1922, Antonio Gramsci travelled to Russia as a representative of the new party.

The Russian mission coincided with the advent of fascism in Italy, and Antonio Gramsci returned with instructions to foster, against the wishes of the PCd'I leadership, a united front of leftist parties against fascism.

In 1924, Antonio Gramsci, now recognised as head of the PCd'I, gained election as a deputy for the Veneto.

Antonio Gramsci started organizing the launch of the official newspaper of the party, called, living in Rome while his family stayed in Moscow.

At its Lyon Congress in January 1926, Antonio Gramsci's theses calling for a united front to restore democracy to Italy were adopted by the party.

In 1926, Joseph Stalin's manoeuvres inside the Bolshevik party moved Antonio Gramsci to write a letter to the Comintern in which he deplored the opposition led by Leon Trotsky but underlined some presumed faults of the leader.

Antonio Gramsci was due for release on 21 April 1937 and planned to retire to Sardinia for convalescence, but a combination of arteriosclerosis, pulmonary tuberculosis, high blood pressure, angina, gout, and acute gastric disorders meant that he was too ill to move.

Antonio Gramsci's ashes are buried in the Cimitero Acattolico in Rome.

Antonio Gramsci was one of the most influential Marxist thinkers of the 20th century, and a particularly key thinker in the development of Western Marxism.

Antonio Gramsci wrote more than 30 notebooks and 3,000 pages of history and analysis during his imprisonment.

Antonio Gramsci calls this union of social forces a historic bloc, taking a term from Georges Sorel.

Antonio Gramsci stated that bourgeois cultural values were tied to folklore, popular culture and religion, and therefore much of his analysis of hegemonic culture is aimed at these.

Antonio Gramsci was impressed by the influence that the Catholic Church had and the care it had taken to prevent an excessive gap from developing between the religion of the learned and that of the less educated.

Antonio Gramsci saw Marxism as a marriage of the purely intellectual critique of religion found in Renaissance humanism and the elements of the Reformation that had appealed to the masses.

Antonio Gramsci gave much thought to the role of intellectuals in society.

Antonio Gramsci stated that all men are intellectuals, in that all have intellectual and rational faculties, but not all men have the social function of intellectuals.

Antonio Gramsci saw modern intellectuals not as talkers but as practical-minded directors and organisers who produced hegemony through ideological apparatuses such as education and the media.

Antonio Gramsci argued that the reason this had not needed to happen in Russia was because the Russian ruling class did not have genuine cultural hegemony.

Antonio Gramsci believed that a final war of manoeuvre was only possible, in the developed and advanced capitalist societies, when the war of position had been won by the organic intellectuals and the working class building a counter-hegemony.

The need to create a working-class culture and a counter-hegemony relates to Antonio Gramsci's call for a kind of education that could develop working-class intellectuals, whose task was not to introduce Marxist ideology into the consciousness of the proletariat as a set of foreign notions but to renovate the existing intellectual activity of the masses and make it natively critical of the status quo.

Antonio Gramsci stresses that the division is purely conceptual and that the two often overlap in reality.

Antonio Gramsci posits that the capitalist state rules through force plus consent: political society is the realm of force and civil society is the realm of consent.

Antonio Gramsci argues that under modern capitalism the bourgeoisie can maintain its economic control by allowing certain demands made by trade unions and mass political parties within civil society to be met by the political sphere.

Antonio Gramsci posits that movements such as reformism and fascism, as well as the scientific management and assembly line methods of Frederick Winslow Taylor and Henry Ford respectively, are examples of this.

Antonio Gramsci believes the proletariat's historical task is to create a regulated society, where political society is diminished and civil society is expanded.

Antonio Gramsci defines the withering away of the state as the full development of civil society's ability to regulate itself.

In contrast, Antonio Gramsci believed Marxism was true in a socially pragmatic sense: by articulating the class consciousness of the proletariat, Marxism expressed the truth of its times better than any other theory.

Antonio Gramsci believed that many trade unionists had settled for a reformist, gradualist approach in that they had refused to struggle on the political front in addition to the economic front.

Antonio Gramsci referred to the views of these trade unionists as vulgar economism, which he equated to covert reformism and liberalism.

Antonio Gramsci defined objectivity in terms of a universal intersubjectivity to be established in a future communist society.

Antonio Gramsci's thought emanates from the organised political left but has become an important figure in current academic discussions within cultural studies and critical theory.

Antonio Gramsci's influence is particularly strong in contemporary political science, such as neo-Gramscianism.

One issue for Antonio Gramsci related to his speaking on topics of violence and when it might be justified or not.

The murder produced a crisis for the Italian fascist regime that Antonio Gramsci could have exploited.

On 16 December 1988, the PCI's newspaper l'Unita published an article on the front page titled "Antonio Gramsci Was Rooting for Juve".