1.

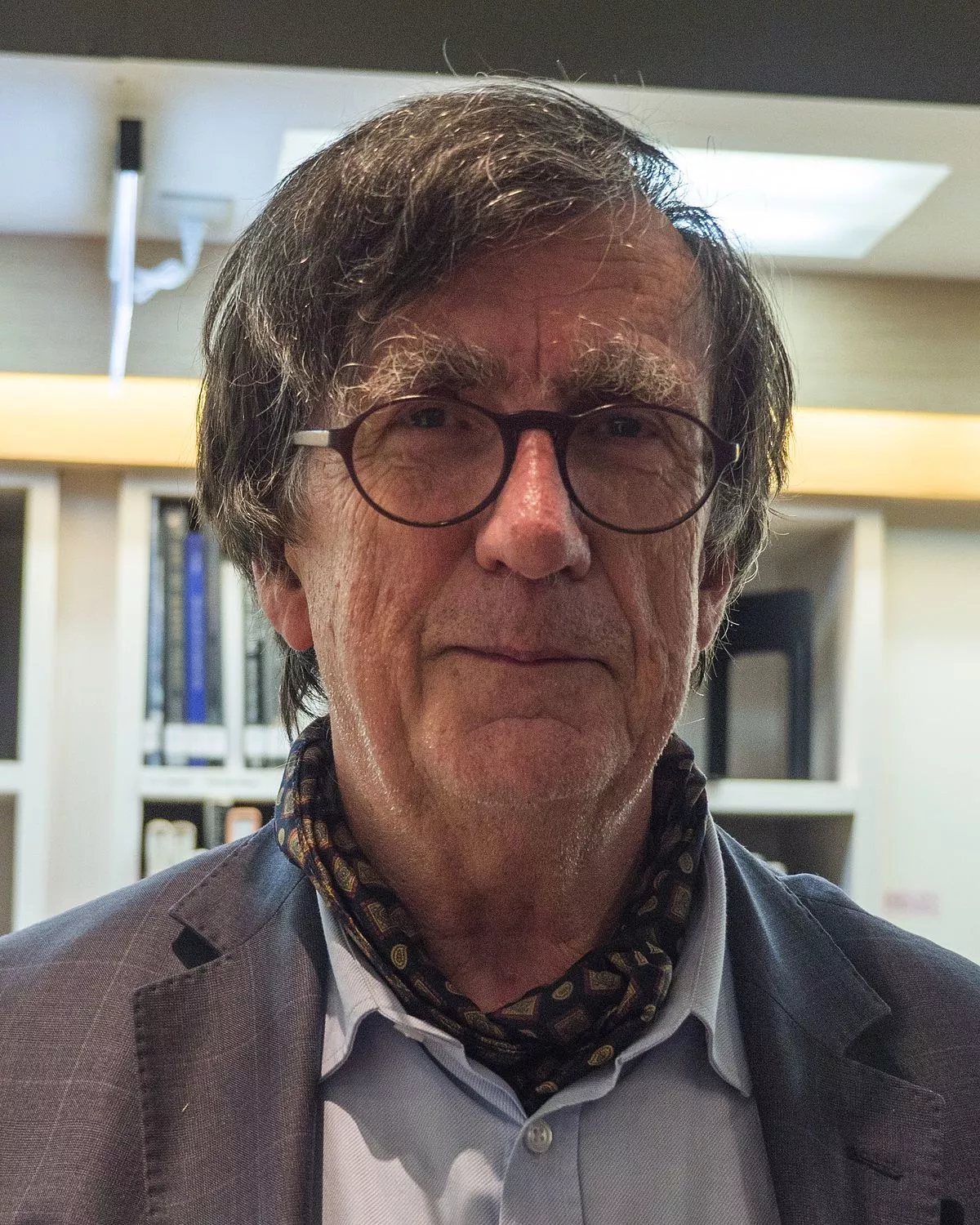

1. Bruno Latour was especially known for his work in the field of science and technology studies.

1.

1. Bruno Latour was especially known for his work in the field of science and technology studies.

Bruno Latour was a Centennial Professor at the London School of Economics.

Bruno Latour said in 2017 that he is interested in helping to rebuild trust in science and that some of the authority of science needs to be regained.

Bruno Latour went on to earn his PhD degree in philosophical theology at the University of Tours in 1975.

Bruno Latour developed an interest in anthropology, and undertook fieldwork in Ivory Coast, on behalf of ORSTOM, which resulted in a brief monograph on decolonization, race, and industrial relations.

Bruno Latour died from pancreatic cancer on 9 October 2022, at the age of 75.

Bruno Latour's papers were contributed to the French National Archives and the Municipal Archives of Beaune.

On 22 May 2008, Latour was awarded an honorary doctorate by the Universite de Montreal on the occasion of an organizational communication conference held in honor of the work of James R Taylor, on whom Latour has had an important influence.

Bruno Latour held several other honorary doctorates, as well as France's Legion d'Honneur.

Bruno Latour rose in importance following the 1979 publication of Laboratory Life: the Social Construction of Scientific Facts with co-author Steve Woolgar.

Bruno Latour argues that the technology failed not because any particular actor killed it, but because the actors failed to sustain it through negotiation and adaptation to a changing social situation.

Bruno Latour encouraged the reader of this anthropology of science to re-think and re-evaluate our mental landscape.

Bruno Latour evaluated the work of scientists and contemplated the contribution of the scientific method to knowledge and work, blurring the distinction across various fields and disciplines.

Bruno Latour argued that society has never really been modern and promoted nonmodernism over postmodernism, modernism, or antimodernism.

Bruno Latour's stance was that we have never been modern and minor divisions alone separate Westerners now from other collectives.

Bruno Latour viewed modernism as an era that believed it had annulled the entire past in its wake.

Bruno Latour presented the antimodern reaction as defending such entities as spirit, rationality, liberty, society, God, or even the past.

Postmoderns, according to Bruno Latour, accepted the modernistic abstractions as if they were real.

Bruno Latour referred to the impossibility of returning to premodernism because it precluded the large scale experimentation which was a benefit of modernism.

Bruno Latour refused the concept of "out there" versus "in here".

Bruno Latour considered nonmoderns to be playing on a different field, one vastly different to that of post-moderns.

Bruno Latour referred to it as much broader and much less polemical, a creation of an unknown territory, which he playfully referred to as the Middle Kingdom.

Pandora's Hope marks a return to the themes Bruno Latour explored in Science in Action and We Have Never Been Modern.

Bruno Latour uses a narrative, anecdotal approach in a number of the essays, describing his work with pedologists in the Amazon rainforest, the development of the pasteurization process, and the research of French atomic scientists at the outbreak of the Second World War.

Some authors have criticized Bruno Latour's methodology, including Katherine Pandora, a history of science professor at the University of Oklahoma.

Bruno Latour suggests that critique, as currently practiced, is bordering on irrelevancy.

Bruno Latour's article has been highly influential within the field of postcritique, an intellectual movement within literary criticism and cultural studies that seeks to find new forms of reading and interpretation that go beyond the methods of critique, critical theory, and ideological criticism.

In Reassembling the Social, Bruno Latour continues a reappraisal of his work, developing what he calls a "practical metaphysics", which calls "real" anything that an actor claims as a source of motivation for action.

Reality, for Bruno Latour, is neither something we have to believe in nor do we have lost access to it in the first place.

Bruno Latour has emphatically problematized the rise of anti-scientific thinking and so-called "alternative facts".

Bruno Latour states that the recent attacks against climate sciences and other disciplines demonstrate that there is a real war on science going on requiring a more intimate cooperation between science and science studies.