1.

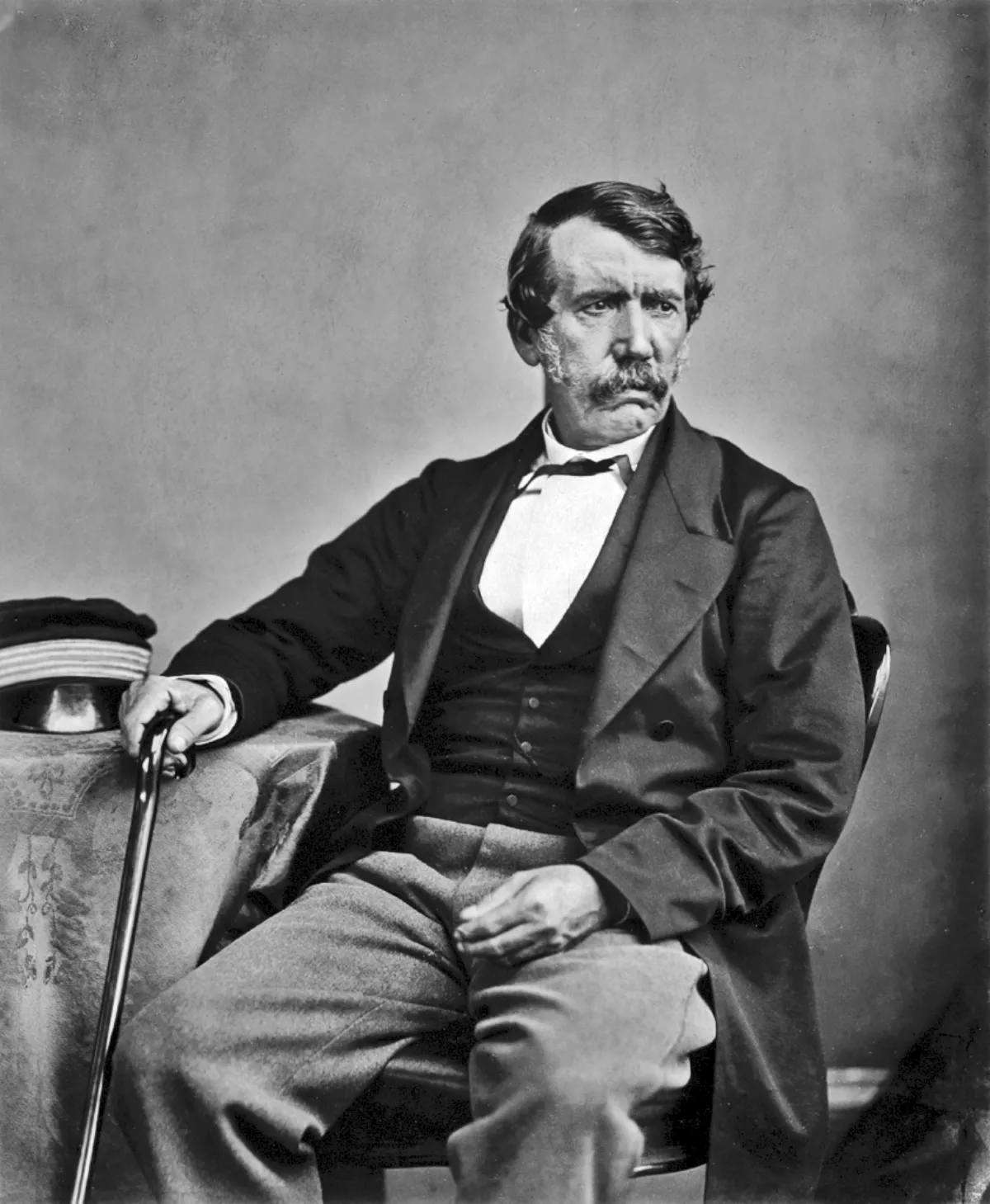

1. David Livingstone came to have a mythic status as a Protestant missionary martyr, working-class "rags-to-riches" inspirational story, scientific investigator and explorer, imperial reformer, anti-slavery crusader, and advocate of British commercial and colonial expansion.