1.

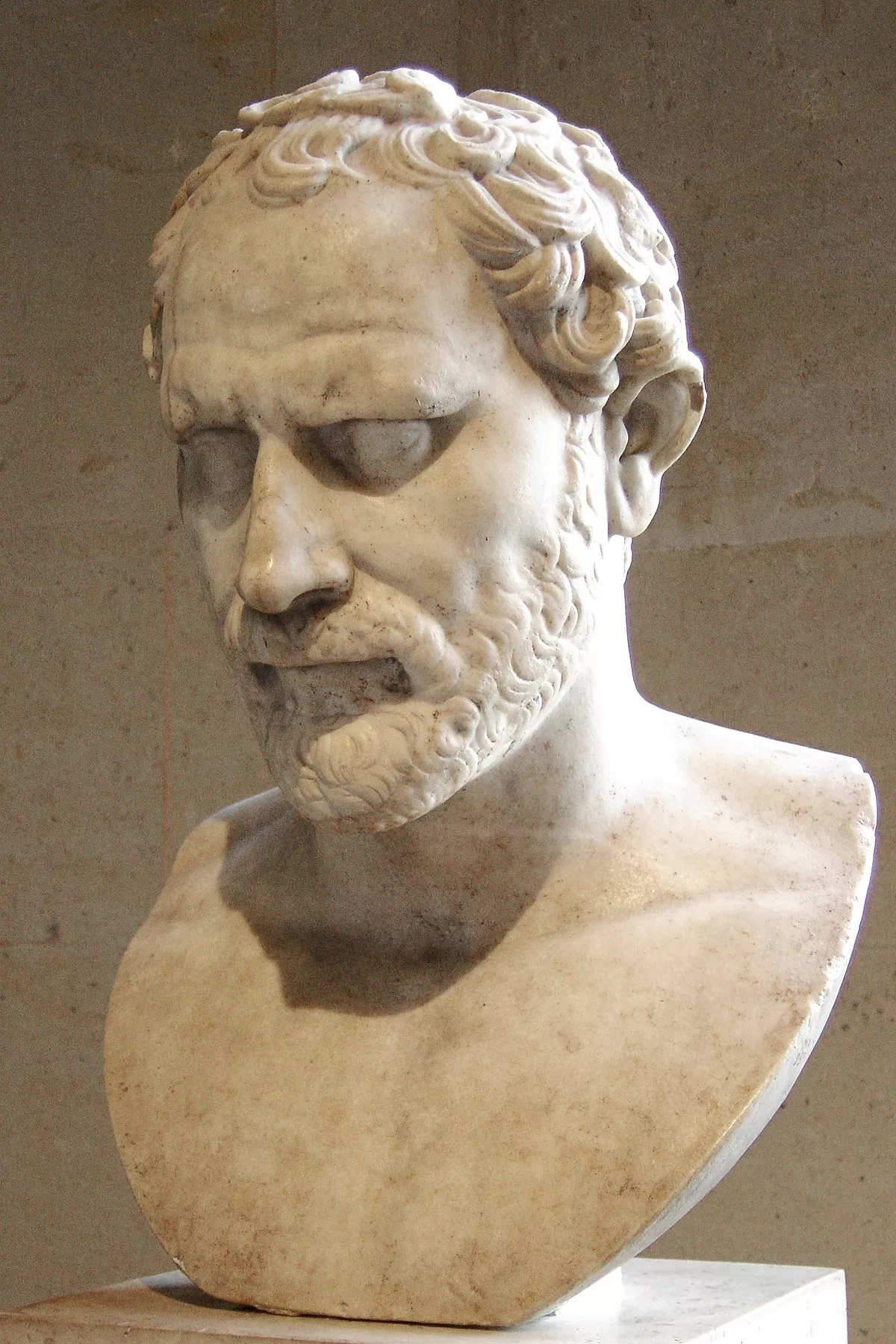

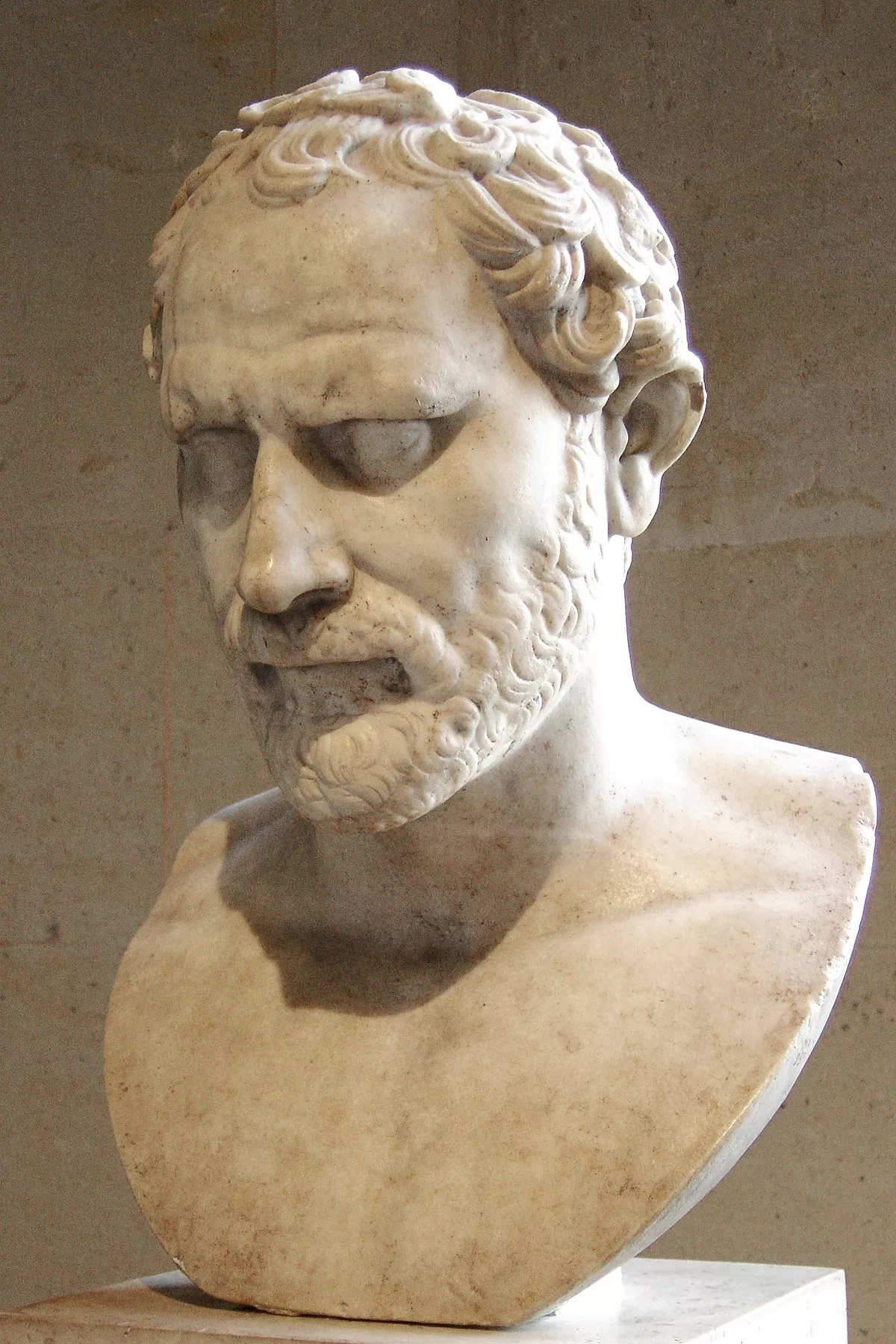

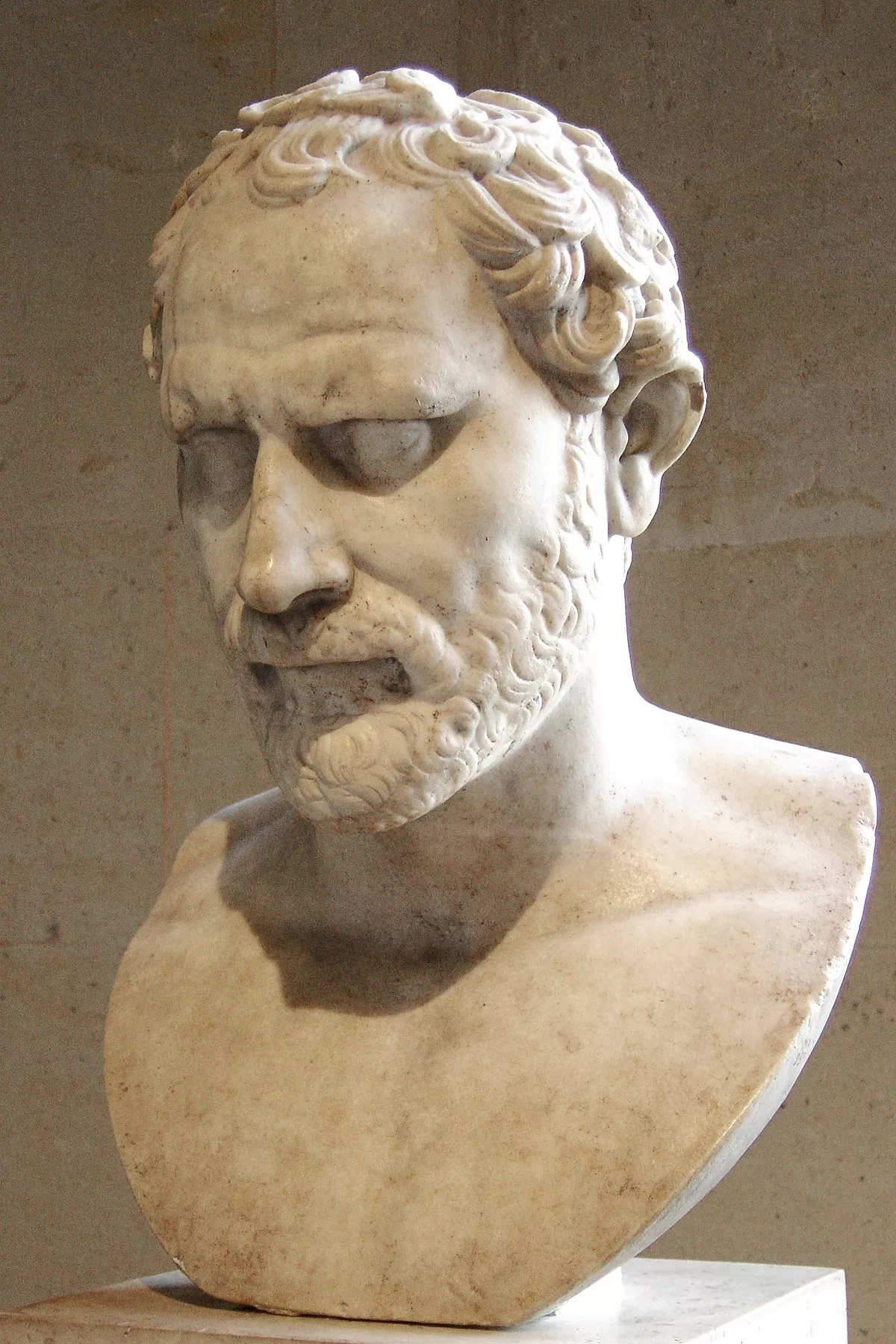

1. Demosthenes learned rhetoric by studying the speeches of previous great orators.

1.

1. Demosthenes learned rhetoric by studying the speeches of previous great orators.

Demosthenes delivered his first judicial speeches at the age of 20, in which he successfully argued that he should gain from his guardians what was left of his inheritance.

Demosthenes went on to devote his most productive years to opposing Macedon's expansion.

Demosthenes sought to preserve his city's freedom and to establish an alliance against Macedon, in an unsuccessful attempt to impede Philip's plans to expand his influence southward, conquering the Greek states.

Demosthenes killed himself to avoid being arrested by Archias of Thurii, Antipater's confidant.

Demosthenes started to learn rhetoric because he wished to take his guardians to court and because he was of "delicate physique" and could not receive gymnastic education, which was customary.

In Parallel Lives, Plutarch states that Demosthenes built an underground study where he practised speaking and shaving one half of his head so that he could not go out in public.

Demosthenes asserted his guardians had left nothing "except the house, and fourteen slaves and thirty silver ".

Demosthenes had a daughter, "the only one who ever called him father", according to Aeschines in a trenchant remark.

Demosthenes's daughter died young and unmarried a few days before Philip II's death.

The slander that Demosthenes' wife slept with the boy suggests that the relationship was contemporary with his marriage.

Aeschines claims that Demosthenes made money out of young rich men, such as Aristarchus, the son of Moschus, whom he allegedly deceived with the pretence that he could make him a great orator.

Demosthenes's crime, according to Aeschines, was to have betrayed his by pillaging his estate, allegedly pretending to be in love with the youth so as to get his hands on the boy's inheritance.

Konstantinos Tsatsos, a Greek professor and academician, believes that Isaeus helped Demosthenes edit his initial judicial orations against his guardians.

Demosthenes undertook a disciplined programme to overcome his weaknesses and improve his delivery, including diction, voice and gestures.

Demosthenes seems to have been able to manage any kind of case, adapting his skills to almost any client, including wealthy and powerful men.

Since Athenian politicians were often indicted by their opponents, there was not always a clear distinction between "private" and "public" cases, and thus a career as a logographer opened the way for Demosthenes to embark on his political career.

Plutarch much later supported this accusation, stating that Demosthenes "was thought to have acted dishonourably" and he accused Demosthenes of writing speeches for both sides.

Contrary to Eubulus' policy, Demosthenes called for an alliance with Megalopolis against Sparta or Thebes, and for supporting the democratic faction of the Rhodians in their internal strife.

Demosthenes's arguments revealed his desire to articulate Athens' needs and interests through a more activist foreign policy, wherever opportunity might provide.

Demosthenes thus laid the foundations for his future political successes and for becoming the leader of his own "party".

Demosthenes thus provided for the first time a plan and specific recommendations for the strategy to be adopted against Philip in the north.

Demosthenes decided to prosecute his wealthy opponent and wrote the judicial oration Against Meidias.

Demosthenes stated that a democratic state perishes if the rule of law is undermined by wealthy and unscrupulous men, and that the citizens acquire power and authority in all state affairs due "to the strength of the laws".

Demosthenes expected that he would hold safely any Athenian possessions that he might seize before the ratification.

Demosthenes accused the other envoys of venality and of facilitating Philip's plans with their stance.

Demosthenes was among those who adopted a pragmatic approach, and recommended this stance in his oration On the Peace.

Demosthenes negotiated with the Athenians an amendment to the Peace of Philocrates.

Demosthenes delivered On the Chersonese and convinced the Athenians not to recall Diopeithes.

Demosthenes told them that it would be "better to die a thousand times than pay court to Philip".

Demosthenes now dominated Athenian politics and was able to considerably weaken the pro-Macedonian faction of Aeschines.

Demosthenes then turned south-east down the Cephissus valley, seized Elateia, and restored the fortifications of the city.

Such was Philip's hatred for Demosthenes that, according to Diodorus Siculus, the King after his victory sneered at the misfortunes of the Athenian statesman.

Demosthenes encouraged the fortification of Athens and was chosen by the ekklesia to deliver the Funeral Oration.

Demosthenes celebrated Philip's assassination and played a leading part in his city's uprising.

Demosthenes did not attack Athens, but demanded the exile of all anti-Macedonian politicians, Demosthenes first of all.

Demosthenes was unrepentant about his past actions and policies and insisted that, when in power, the constant aim of his policies was the honour and the ascendancy of his country; and on every occasion and in all business he preserved his loyalty to Athens.

Demosthenes finally defeated Aeschines, although his enemy's objections, though politically-motivated, to the crowning were arguably valid from a legal point of view.

Unable to pay this huge amount, Demosthenes escaped and only returned to Athens nine months later, after the death of Alexander.

Mogens Hansen notes that many Athenian leaders, Demosthenes included, made fortunes out of their political activism, especially by taking bribes from fellow citizens and such foreign states as Macedonia and Persia.

Demosthenes received vast sums for the many decrees and laws he proposed.

Demosthenes escaped to a sanctuary on the island of Kalaureia, where he was later discovered by Archias, a confidant of Antipater.

Demosthenes died by suicide before his capture by taking poison out of a reed, pretending he wanted to write a letter to his family.

The historian maintains that Demosthenes measured everything by the interests of his own city, imagining that all the Greeks ought to have their eyes fixed upon Athens.

Therefore, Demosthenes is accused of misjudging events, opponents and opportunities and of being unable to foresee Philip's inevitable triumph.

Demosthenes is criticised for having overrated Athens's capacity to revive and challenge Macedon.

Demosthenes's city had lost most of its Aegean allies, whereas Philip had consolidated his hold over Macedonia and was master of enormous mineral wealth.

Chris Carey, a professor of Greek in UCL, concludes that Demosthenes was a better orator and political operator than strategist.

Athens was asked by Philip to sacrifice its freedom and its democracy, while Demosthenes longed for the city's brilliance.

Demosthenes endeavoured to revive its imperilled values and, thus, he became an "educator of the people".

The fact that Demosthenes fought at the battle of Chaeronea as a hoplite indicates that he lacked any military skills.

Demosthenes dealt in policies and ideas, and war was not his business.

Demosthenes is, therefore, regarded as a consummate orator, adept in the techniques of oratory, which are brought together in his work.

Demosthenes had no wit, no humour, no vivacity, in our acceptance of these terms.

Demosthenes was apt at combining abruptness with the extended period, brevity with breadth.

Demosthenes's language is simple and natural, never far-fetched or artificial.

The main criticism of Demosthenes' art seems to have rested chiefly on his known reluctance to speak ; he often declined to comment on subjects he had not studied beforehand.

Demosthenes relied heavily on the different aspects of ethos, especially phronesis.

One tactic that Demosthenes used during his philippics was foresight.

Demosthenes pleaded with his audience to predict the potential of being defeated, and to prepare.

Demosthenes appealed to pathos through patriotism and introducing the atrocities that would befall Athens if it was taken over by Philip.

Demosthenes was a master at "self-fashioning" by referring to his previous accomplishments, and renewing his credibility.

Demosthenes took pride in not relying on attractive words but rather simple, effective prose.

Demosthenes was mindful of his arrangement, he used clauses to create patterns that would make seemingly complex sentences easy for the hearer to follow.

Demosthenes is widely considered one of the greatest orators of all time, and his fame has continued down the ages.

Demosthenes was read more than any other ancient orator; only Cicero offered any real competition.

For Thomas Wilson, who first published translation of his speeches into English, Demosthenes was not only an eloquent orator, but, mainly, an authoritative statesman, "a source of wisdom".

French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau was among those who idealised Demosthenes and wrote a book about him.

Irrespective of their status, the speeches attributed to Demosthenes are often grouped in three genres first defined by Aristotle:.

Tsatsos and the philologist Henri Weil believe that there is no indication that Demosthenes was a pupil of Plato or Isocrates.

Peck believes that Demosthenes continued to study under Isaeus for the space of four years after he had reached his majority.

Aeschines maintained that Demosthenes was bribed to drop his charges against Meidias in return for a payment of thirty mnai.

Plutarch argued that Demosthenes accepted the bribe out of fear of Meidias's power.

Weil agreed that Demosthenes never delivered Against Meidias, but believed that he dropped the charges for political reasons.

In 1956, Hartmut Erbse partly challenged Bockh's conclusions, when he argued that Against Meidias was a finished speech that could have been delivered in court, but Erbse then sided with George Grote, by accepting that, after Demosthenes secured a judgment in his favour, he reached some kind of settlement with Meidias.

Kenneth Dover endorsed Aeschines's account, and argued that, although the speech was never delivered in court, Demosthenes put into circulation an attack on Meidias.

Aeschines reproached Demosthenes for being silent as to the seventy talents of the king's gold which he allegedly seized and embezzled.

Aeschines and Dinarchus maintained that when the Arcadians offered their services for ten talents, Demosthenes refused to furnish the money to the Thebans, who were conducting the negotiations, and so the Arcadians sold out to the Macedonians.

Demosthenes narrates the following story: Shortly after Harpalus ran away from Athens, he was put to death by the servants who were attending him, though some assert that he was assassinated.