1.

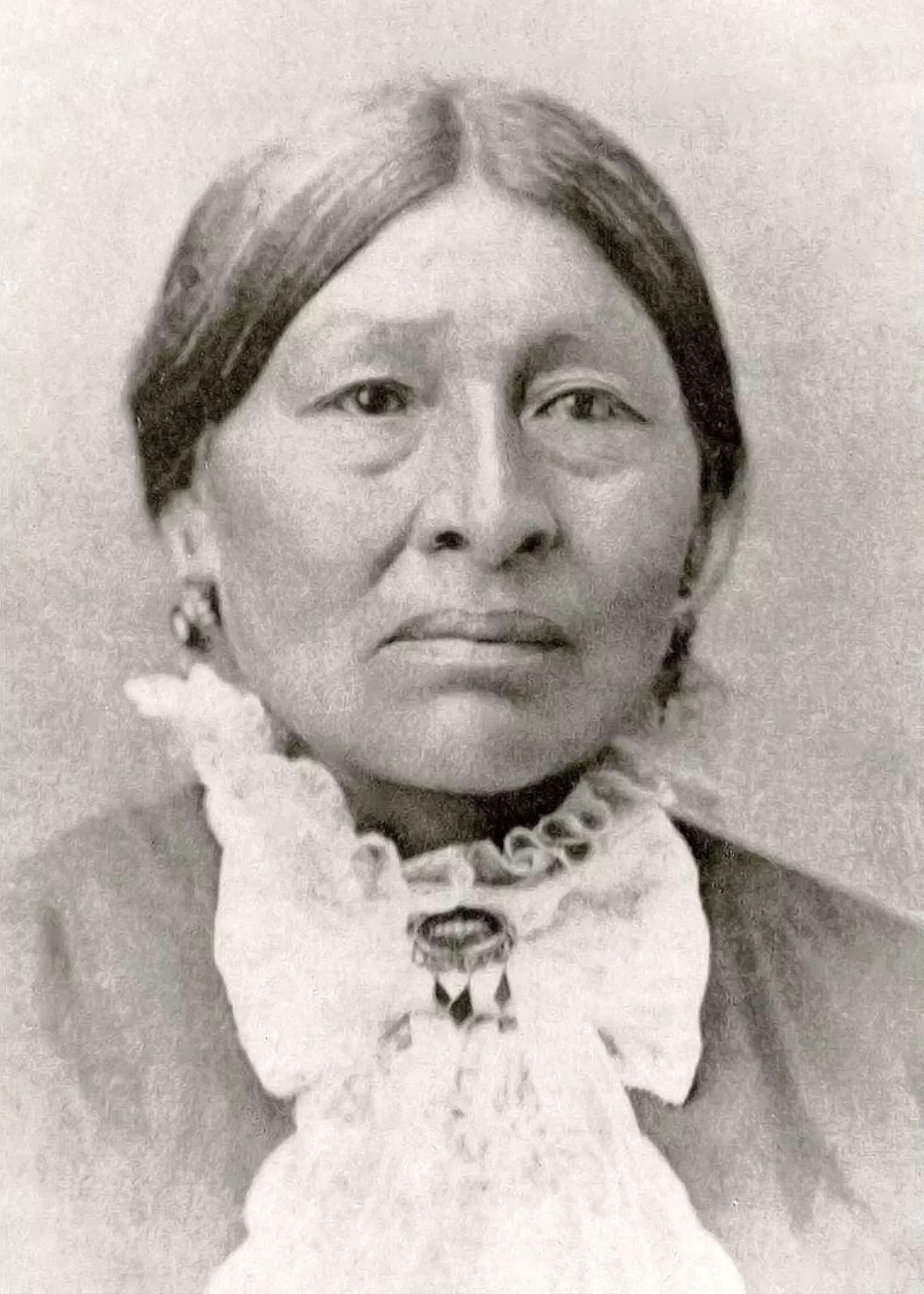

1. Eagle Woman That All Look At was a Lakota activist, diplomat, trader, and translator, who was known for her efforts mediating the conflicts between white settlers, the United States government, and the Sioux.

1.

1. Eagle Woman That All Look At was a Lakota activist, diplomat, trader, and translator, who was known for her efforts mediating the conflicts between white settlers, the United States government, and the Sioux.

Eagle Woman is credited with being the only woman recognized as a chief among the Sioux.

Eagle Woman materially supported the Sioux when the US government forced tribes to sustain themselves on barren reservation lands.

Eagle Woman was in part responsible for the party of leaders sent to sign the Second Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, though she opposed the Standing Rock treaty of 1876, and became the first woman to sign a treaty with the United States government in 1882.

Eagle Woman won a local trade war, when government official attempted to shut down her trading post to establish a monopoly on the reservation, and continued to serve as a mediator and community leader throughout white encroachment on native lands during the Black Hills Gold Rush, including being selected by the US government as part of a delegation to Washington, DC in 1872.

Eagle Woman continued aiding the tribes in adjusting to reservation life until her death in 1888.

Eagle Woman was born in a Sioux lodge near the Missouri River, around 45 miles south of modern-day Pierre, South Dakota, to a distinguished leader of the "peace-seeking" Two Kettles Tribe, Chief Two Lance, and Rosy Light of Dawn, a Hunkpapa.

Eagle Woman was the youngest of eight children, and her later leadership would be influenced by the example set by her father.

Eagle Woman spent her childhood in what would become western South Dakota and had little contact with white culture or government.

Eagle Woman was 13 when her father died in 1833, to be buried by the Cheyenne River, and in 1837, her mother died of smallpox after the tribes fled the rivers to escape the disease.

Eagle Woman, while living at the fort, adopted the settlers' lifestyle, but as Picotte often spent long periods of time away, she would return to her tribe.

Eagle Woman had two daughters with Picotte, who in 1848 retired and moved back to live with his white wife in St Louis.

In 1850, Eagle Woman married Picotte's protege at the company, Charles Galpin, with whom she had two more daughters and three sons, all of whom were given a European education.

Eagle Woman "frequently spoke out against cruelty of any kind, whether committed by whites or by Indians," and she found opportunity to do so throughout her life.

En route, the couple was surrounded by Santee Sioux who had recently led the Lake Shetek massacre; however, one of the warriors recognized Eagle Woman and allowed them passage after she informed them that she had gifts for the local lodge and was transporting one of her sons for burial.

Eagle Woman later recounted that she had to persuade Sitting Bull's people not to kill De Smet, after his delegation's arrival was met with a band of hostile warriors.

Formerly an advocate for peace, Eagle Woman found a new purpose in helping her people adapt to their new conditions, now that peace had been achieved, albeit temporarily.

Eagle Woman continued her activism for peace by defusing conflicts in person and alone, and by refusing to trade in firearms or ammunition.

One of the white men Eagle Woman saved on that day was probably Lieutenant William Harmon, who later married her daughter Lulu.

In 1873, the agency at Grand River was moved to Standing Rock on account of flooding, and Eagle Woman followed, setting up her new trading post there.

Eagle Woman herself helped to mediate this dispute that had delayed the shuttering of her own store, and Harmon wrote on her behalf to congressman John T Averill.

The meeting accomplished nothing, and negotiations broke down on the verge of violence, which Eagle Woman helped to mediate and avoid.

Eagle Woman did not support the "Sell or Starve" policies and the Act of 1877, which resolved to cut off all government rations to the Sioux until they agreed to peacefully cede the Black Hills.

Eagle Woman spent her final years at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation with friends, her daughters, and grandchildren.

Eagle Woman met briefly with Sitting Bull in 1881 after his surrender, as he passed through Fort Yates on his way to internment as a prisoner of war at Fort Randall.

Eagle Woman wrote to her stepson, Charles Picotte, at Yankton Agency to look after Sitting Bull.

On December 18,1888, Eagle Woman died at her daughter Alma's home, the Cannonball Ranch in modern-day Morton County, North Dakota.

Eagle Woman was buried next to Galpin at the Fort Yates cemetery.

Eagle Woman was inducted into the South Dakota Hall of Fame as a Champion of Excellence in 2010, for her "attempts at peaceful compromise" between "Native American Indian and white societies".