1.

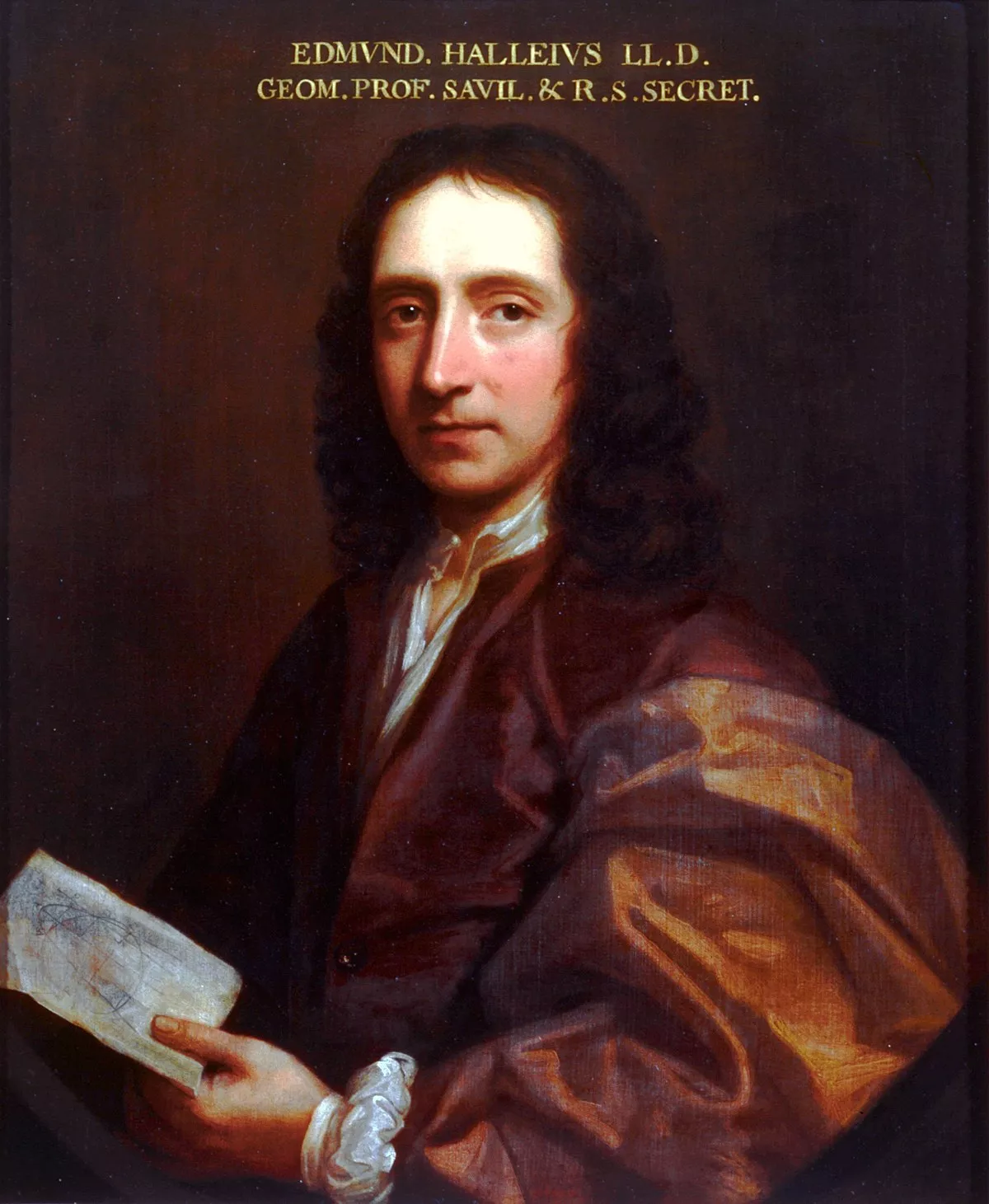

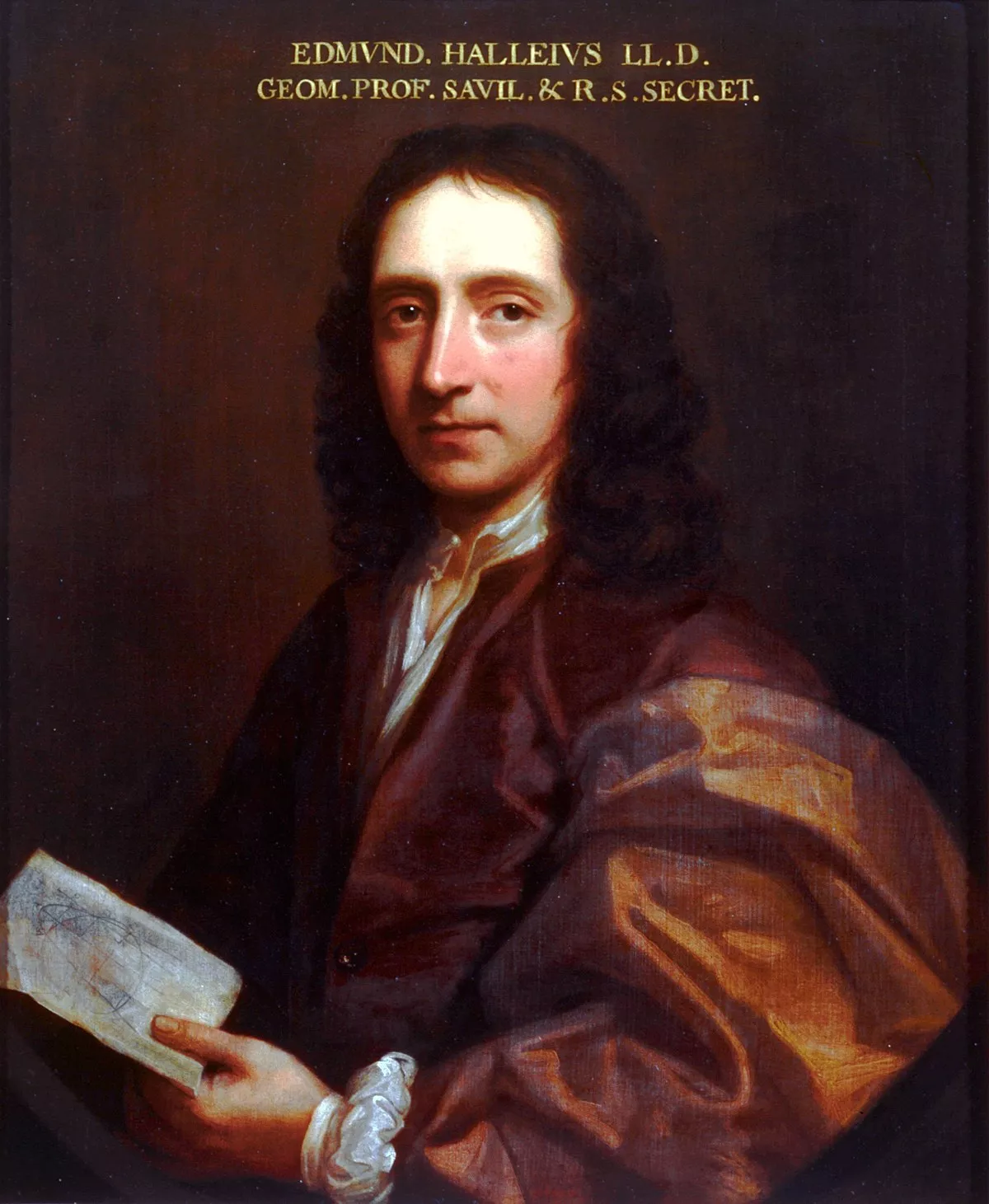

1. Edmond Halley was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

Edmond Halley realised that a similar transit of Venus could be used to determine the distances between Earth, Venus, and the Sun.

Edmond Halley studied at St Paul's School, where he developed his initial interest in astronomy, and was elected captain of the school in 1671.

Edmond Halley took a twenty-four-foot long telescope with him, apparently paid for by his father.

In 1676, Flamsteed helped Edmond Halley publish his first paper, titled "A Direct and Geometrical Method of Finding the Aphelia, Eccentricities, and Proportions of the Primary Planets, Without Supposing Equality in Angular Motion", about planetary orbits, in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

Edmond Halley chose the south Atlantic island of Saint Helena, from which he would be able to observe not only the southern stars, but some of the northern stars with which to cross-reference them.

Just a few days before, Edmond Halley had been elected as a fellow of the Royal Society, at the age of 22.

In mid-1679, Edmond Halley went to Danzig on behalf of the Society to help resolve a dispute: because astronomer Johannes Hevelius' observing instruments were not equipped with telescopic sights, Flamsteed and Hooke had questioned the accuracy of his observations; Edmond Halley stayed with Hevelius and checked his observations, finding that they were quite precise.

In early 1686, Edmond Halley was elected to the Royal Society's new position of secretary, requiring him to give up his fellowship and manage correspondence and meetings, as well as edit the Philosophical Transactions.

Also in 1686, Edmond Halley published the second part of the results from his Helenian expedition, being a paper and chart on trade winds and monsoons.

Edmond Halley established the relationship between barometric pressure and height above sea level.

Edmond Halley's charts were an important contribution to the emerging field of information visualisation.

Edmond Halley spent most of his time on lunar observations, but was interested in the problems of gravity.

Edmond Halley asked to see the calculations and was told by Newton that he could not find them, but promised to redo them and send them on later, which he eventually did, in a short treatise titled On the motion of bodies in an orbit.

In 1691, Edmond Halley built a diving bell, a device in which the atmosphere was replenished by way of weighted barrels of air sent down from the surface.

Edmond Halley's bell was of little use for practical salvage work, as it was very heavy, but he made improvements to it over time, later extending his underwater exposure time to over 4 hours.

Edmond Halley suffered one of the earliest recorded cases of middle ear barotrauma.

That same year, at a meeting of the Royal Society, Edmond Halley introduced a rudimentary working model of a magnetic compass using a liquid-filled housing to damp the swing and wobble of the magnetised needle.

In 1691, Edmond Halley sought the post of Savilian Professor of Astronomy at Oxford.

Edmond Halley's candidacy was opposed by both the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Tillotson, and Bishop Stillingfleet, and the post went instead to David Gregory, who had Newton's support.

In 1692, Edmond Halley put forth the idea of a hollow Earth consisting of a shell about 500 miles thick, two inner concentric shells and an innermost core.

Edmond Halley suggested that atmospheres separated these shells, and that each shell had its own magnetic poles, with each sphere rotating at a different speed.

Edmond Halley envisaged each inner region as having an atmosphere and being luminous, and speculated that escaping gas caused the aurora borealis.

In 1693 Edmond Halley published an article on life annuities, which featured an analysis of age-at-death on the basis of the Breslau statistics Caspar Neumann had been able to provide.

The Royal Society censured Edmond Halley for suggesting in 1694 that the story of Noah's flood might be an account of a cometary impact.

In 1698, at the behest of King William III, Edmond Halley was given command of the Paramour, a 52 feet pink, so that he could carry out investigations in the South Atlantic into the laws governing the variation of the compass, as well as to refine the coordinates of the English colonies in the Americas.

The result was a mild rebuke for his men, and dissatisfaction for Edmond Halley, who felt the court had been too lenient.

In 1701, Edmond Halley made a third and final voyage on the Paramour to study the tides of the English Channel.

The preface to Awnsham and John Churchill's collection of voyages and travels, supposedly written by John Locke or by Edmond Halley, valourised expeditions such as these as part of a grand expansion of European knowledge of the world:.

Edmond Halley did not live to witness the comet's return, but when it did, the comet became generally known as Edmond Halley's Comet.

Edmond Halley completed a new translation of the first four books from the original Greek that had been started by the late David Gregory.

Edmond Halley published these along with his own reconstruction of Book VIII in the first complete Latin edition in 1710.

In 1716, Edmond Halley suggested a high-precision measurement of the distance between the Earth and the Sun by timing the transit of Venus.

In 1720, together with his friend the antiquarian William Stukeley, Edmond Halley participated in the first attempt to scientifically date Stonehenge.

Edmond Halley succeeded John Flamsteed in 1720 as Astronomer Royal, a position Edmond Halley held until his death in 1742 at the age of 85.

Edmond Halley was buried in the graveyard of the old church of St Margaret's, Lee, at Lee Terrace, Blackheath.

Edmond Halley was interred in the same vault as the Astronomer Royal John Pond; the unmarked grave of the Astronomer Royal Nathaniel Bliss is nearby.

Edmond Halley's marked grave can be seen at St Margaret's Church, Lee Terrace.

Edmond Halley married Mary Tooke in 1682 and settled in Islington.