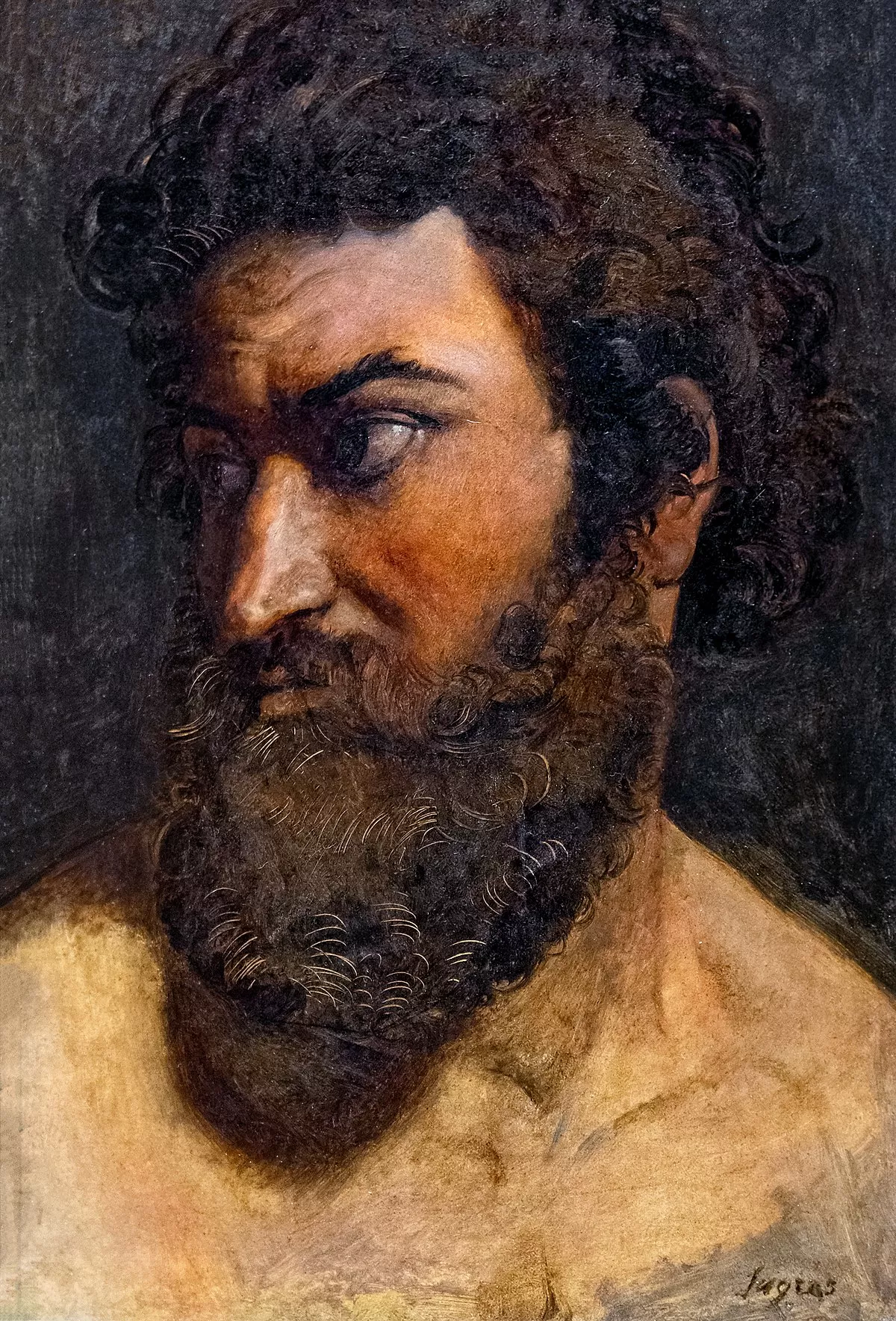

1.

1. Erasistratus was a Greek anatomist and royal physician under Seleucus I Nicator of Syria.

1.

1. Erasistratus was a Greek anatomist and royal physician under Seleucus I Nicator of Syria.

Erasistratus is credited for his description of the valves of the heart, and he concluded that the heart was not the center of sensations, but that it instead functioned as a pump.

Erasistratus was among the first to distinguish between veins and arteries, believing that the arteries were full of air and that they carried the "animal spirit".

Erasistratus considered atoms to be the essential body element, and he believed they were vitalized by the pneuma that circulated through the nerves.

Erasistratus thought that the nerves moved a nervous spirit from the brain.

Erasistratus then differentiated between the function of the sensory and motor nerves, and linked them to the brain.

Erasistratus is credited with one of the first in-depth descriptions of the cerebrum and cerebellum.

Erasistratus is regarded by some as the founder of physiology.

Erasistratus is generally supposed to have been born at Ioulis on the island of Ceos, though Stephanus of Byzantium refers to him as a native of Cos; Galen, as a native of Chios; and the emperor Julian, as a native of Samos.

Erasistratus was a pupil of Chrysippus of Cnidos, Metrodorus, and apparently Theophrastus.

Erasistratus lived for some time at the court of Seleucus I Nicator, where he acquired great reputation by discovering the disease of Antiochus I Soter, the king's eldest son, probably 294 BC.

Erasistratus confirmed his conjecture when he observed that the skin of Antiochus grew hotter, his colour deeper, and his pulse quicker whenever Stratonice came near him, while none of these symptoms occurred on any other occasion.

The king protested that he would most gladly; upon which Erasistratus told him that it was indeed his own wife who had inspired his passion, and that he chose rather to die than to disclose his secret.

Erasistratus appears to have died in Asia Minor, as the Suda mentions that he was buried by mount Mycale in Ionia.

Erasistratus had numerous pupils and followers, and a medical school bearing his name continued to exist at Smyrna in Ionia nearly till the time of Strabo, about the beginning of the 1st century.

Erasistratus wrote many works on anatomy, practical medicine and pharmacy, of which only the titles remain, together with a great number of short fragments preserved by Galen, Caelius Aurelianus, and other ancient writers.

Erasistratus appears to have been very near the discovery of the circulation of the blood, for in a passage preserved by Galen he says:.

Erasistratus had a theory that if an artery was traumatized then it would be possible however to find blood at that point, not due to blood being present within the artery itself, but rather because of the body functioning like a vacuum.

Erasistratus made observations on the morphology of the heart, describing the pulmonary artery and the aorta to have a sigmoid shape, a name which is still used presently.

Erasistratus appears to have paid particular attention to the anatomy of the brain, and in a passage from his works preserved by Galen he speaks as if he had himself dissected a human brain.

Galen says that before Erasistratus had more closely examined into the origin of the nerves, he imagined that they arose from the dura mater and not from the substance of the brain; and that it was not until he was advanced in life that he satisfied himself by actual inspection that such was not the case.

Erasistratus asserted that the spleen, the bile, and several other parts of the body, were entirely useless to animals.

Erasistratus believed that fluids, when drunk, passed through the esophagus into the stomach.

Erasistratus is supposed to have been the first person who added to the word arteria, which had hitherto designated the canal leading from the mouth to the lungs, the epithet tracheia, to distinguish it from the arteries, and hence to have been the originator of the modern name trachea.

Erasistratus attributed the sensation of hunger to emptiness of the stomach, and said that the Scythians were accustomed to tie a belt tightly round their middle, to enable them to abstain from food for a longer time without suffering inconvenience.

Erasistratus accounted for diseases in the same way, and supposed that as long as the pneuma continued to fill the arteries and the blood was confined to the veins, the individual was in good health; but that when the blood from some cause or other got forced into the arteries, inflammation and fever was the consequence.

Erasistratus was against bloodletting likely due to his theory of plethora.

Much to the disagreement that Galen had towards Erasistratus's views regarding phlebotomy, the Alexandrian physician was said by Galen in his work entitled, Bloodletting, against the Erasistrateans at Rome, to have disregarded the importance of the practice and rather suggested alternative methods.

Notably, Erasistratus suggests the bandaging of a patient's armpits and groin to achieve the desired results associated with phlebotomy.

Galen continues in his work to highly criticize this viewpoint that the Alexandrian physician had regarding the medical practice, and points out that Erasistratus did not give enough evidence to support the avoidance of phlebotomy for other treatments.

Erasistratus is frequently mentioned in historical documents with other significant figures of both his time period of the 3rd and 4th century BC and afterwards thanks to his accomplishments and advancements in the field of medicine.

Herophilus believed that the arteries carried a mixture of pneuma and blood, while Erasistratus believed that they solely carried pneuma.

Erasistratus is said to have natural philosophical views as compared to others during the time, paving the way for the teaching of methodologists in the field of medicine.

Erasistratus believed that pneuma received the air it needed from the lungs.

Galen frequently notes the past ideas that had become prevalent from the work of Erasistratus when comparing it to that of his work and ideas.