1.

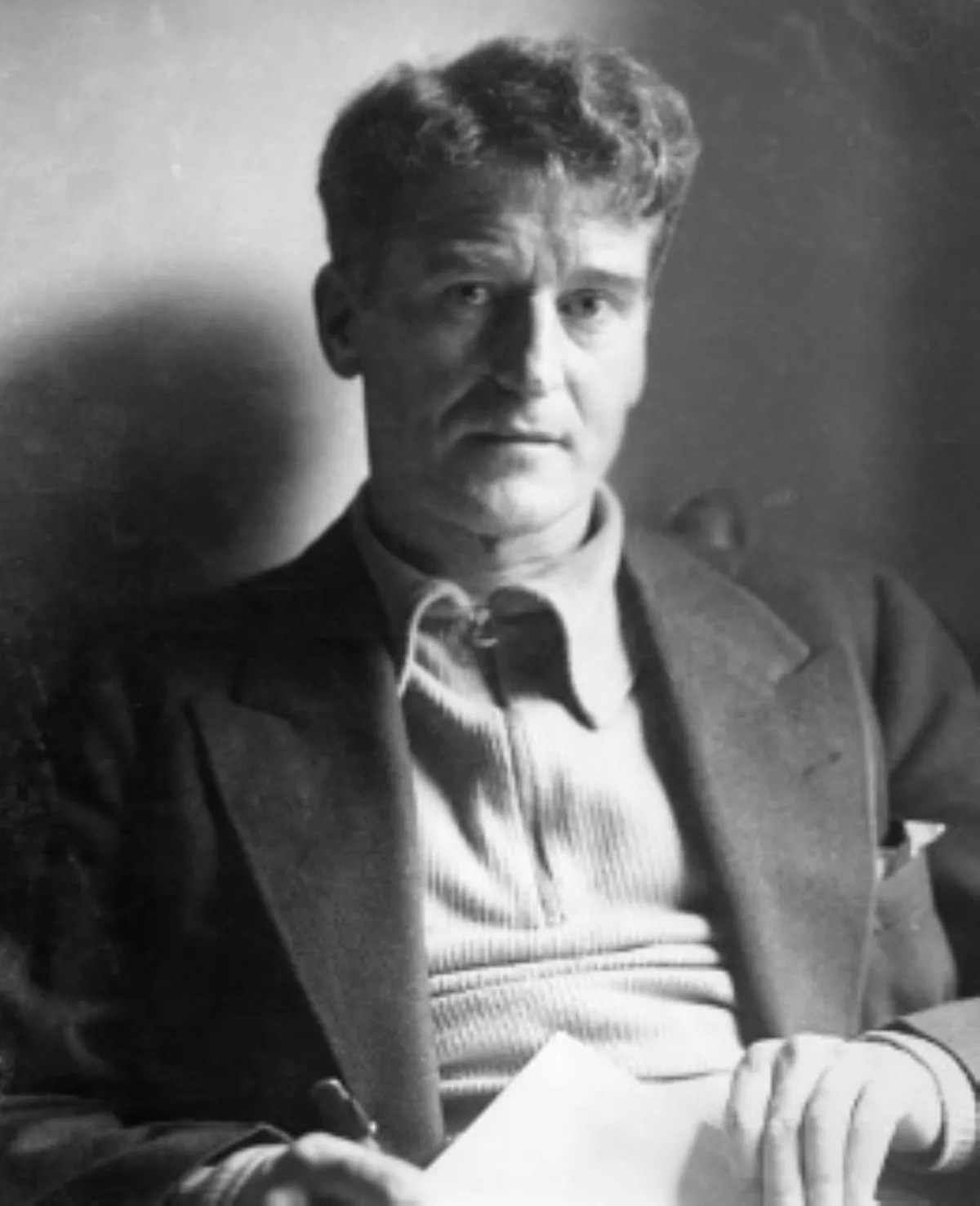

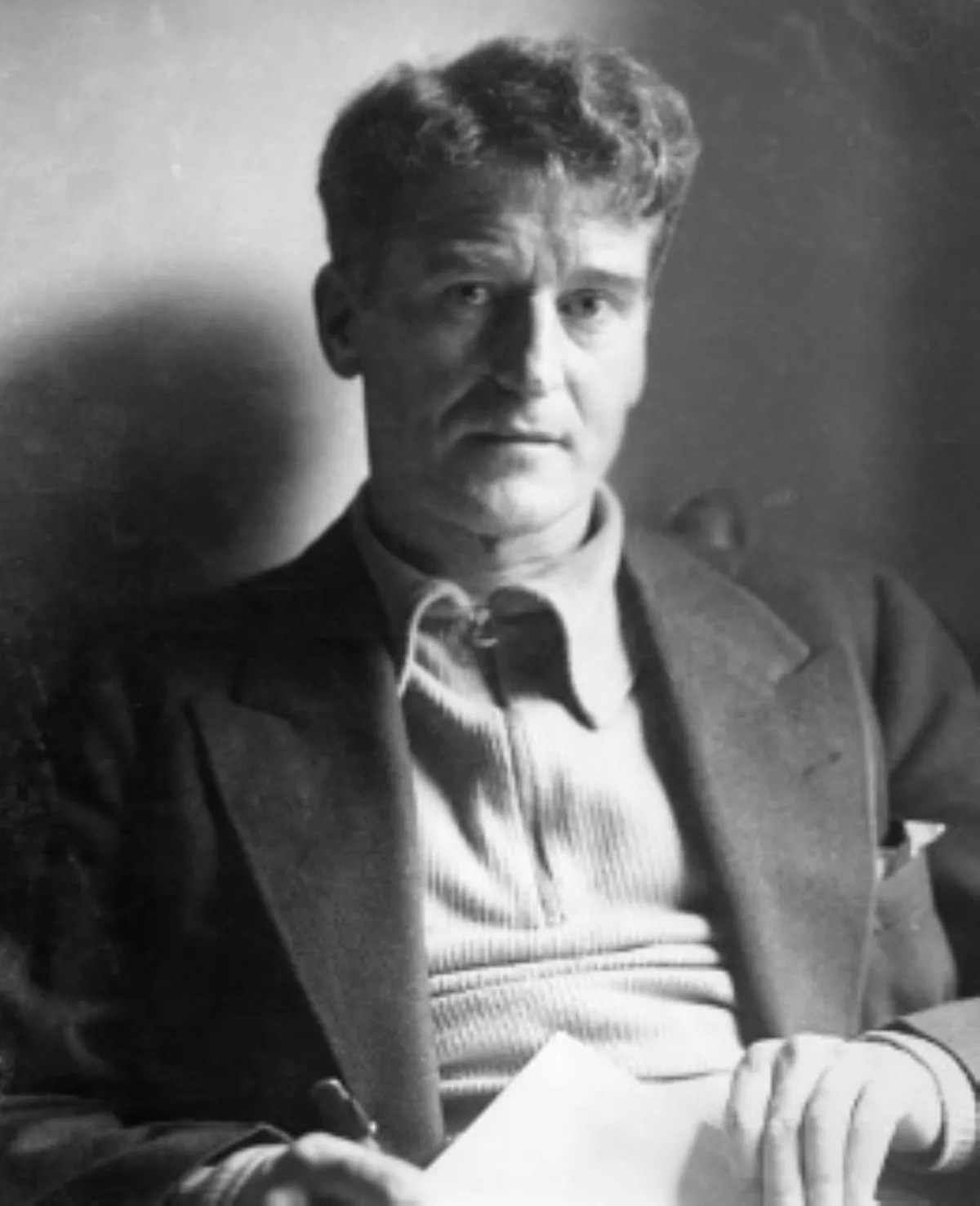

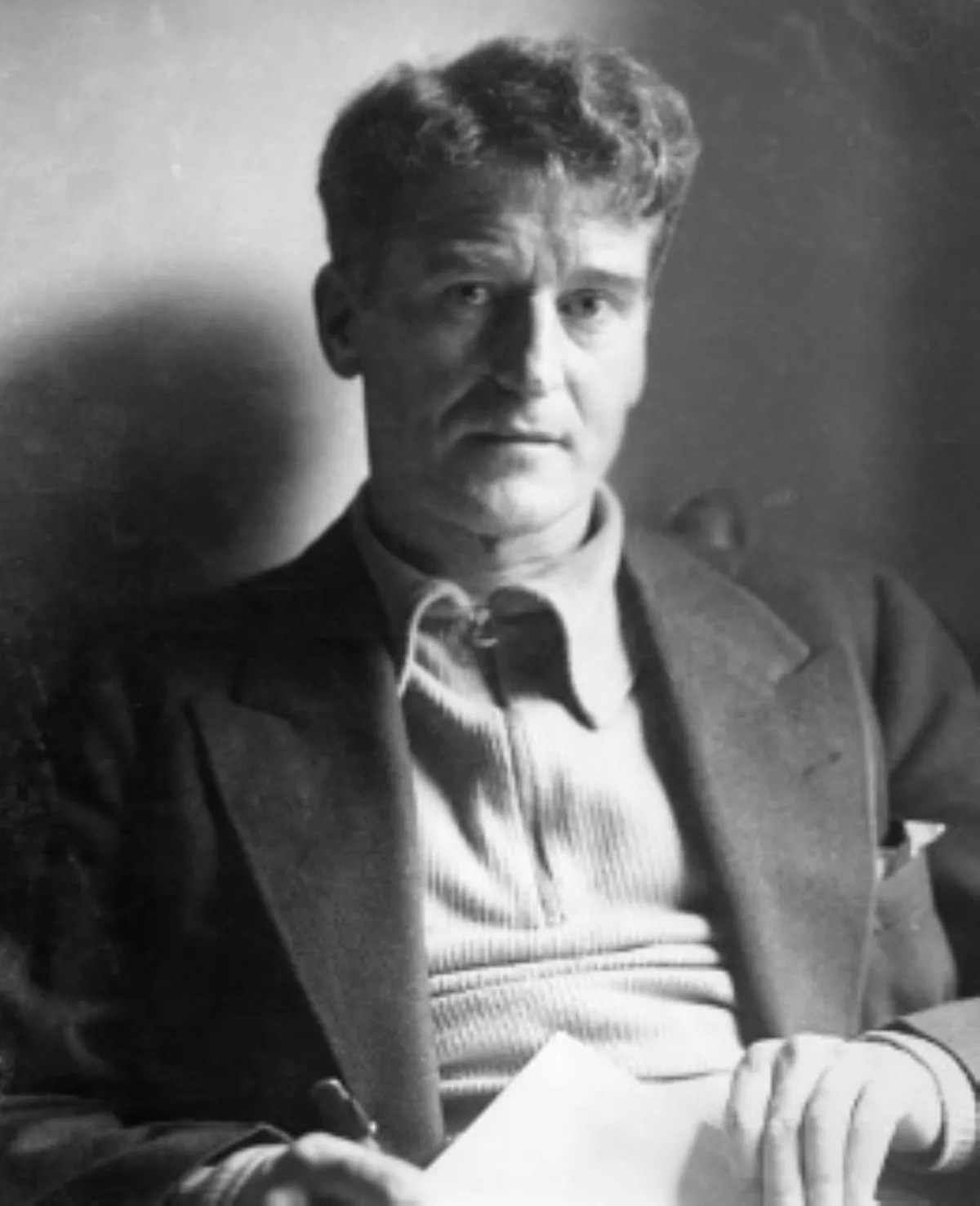

1. Ernie O'Malley endured forty-one days on hunger strike in late 1923 and was the very last republican to be released from internment by the Free State authorities in July 1924.

1.

1. Ernie O'Malley endured forty-one days on hunger strike in late 1923 and was the very last republican to be released from internment by the Free State authorities in July 1924.

Ernie O'Malley then spent two years in Europe and North Africa to improve his health before returning to Ireland.

Ernie O'Malley became well known in the arts and had a deep interest in folklore.

Ernie O'Malley wrote two memoirs, On Another Man's Wound and The Singing Flame, and two histories, Raids and Rallies and Rising-Out: Sean Connolly of Longford, covering his early life, the war of independence and the civil war period.

Ernie O'Malley interviewed 450 people who participated in the war of independence and the civil war.

Ernie O'Malley was born in Castlebar, County Mayo, on 26 May 1897.

Ernie O'Malley's was a middle class Catholic family in which he was the second of eleven children born to local man Luke Malley and his wife Marion from Castlereagh, County Roscommon.

Ernie O'Malley noted the importance of the police and that officers would nod in courtesy when his father walked by.

Ernie O'Malley remembered RIC men dressed in suits leaving the town to keep peace at Orange parades in the North.

Ernie O'Malley's father was a solicitor's clerk with conservative Irish nationalist politics: he supported the Irish Parliamentary Party.

The family spent the summer at Clew Bay, where Ernie O'Malley developed a lifelong love of the sea.

Ernie O'Malley recounts meeting an old woman who, prophetically, spoke of fighting and trouble in store for him.

The Malleys moved to Dublin in 1906 when Ernie O'Malley was still a boy.

Ernie O'Malley's father obtained a post with the Congested Districts Board and later became a senior civil servant.

Ernie O'Malley considered that he received a reasonably good education at the O'Connell Christian Brothers School in North Richmond St, where he "rubbed shoulders with all classes and conditions".

Ernie O'Malley was later to win a scholarship to study medicine at University College Dublin.

Ernie O'Malley witnessed heavy violence by the police and was in favour of the strikers' cause.

Ernie O'Malley heard of the Howth gun-running incident that occurred in July 1914 and that three people had been killed in the aftermath.

Ernie O'Malley was initially indifferent to the Irish Citizen Army and the Irish Volunteers, whom he had observed drilling in the mountains.

At that time, Ernie O'Malley was planning to join the British Army, like his friends and brothers.

Ernie O'Malley was in his first year of studying medicine at University College Dublin when the Easter Rising, which was to leave an "indelible mark" on him, convulsed the city in April 1916.

Ernie O'Malley recalls that, on Easter Monday, he saw a new flag of green, white and orange on top of the General Post Office in Sackville Street and later read the Proclamation of the Republic at the base of Nelson's Pillar.

Ernie O'Malley was almost persuaded by some anti-rising friends to join them in defending Trinity College against the rebels should they attempt to take it.

Ernie O'Malley writes that he was offered the use of a rifle if he would return later and assist them.

On his way home, he encountered an acquaintance who observed that Ernie O'Malley would be shooting fellow Irishmen, for whom he had no hatred, if he took that rifle.

However, Ernie O'Malley recalls that his main feeling was one of mere annoyance at the inconvenience the fighting was causing.

Ernie O'Malley kept a diary of what he saw during the rising, including looting.

Ernie O'Malley was unable to come and go freely from the family home, to which he was not given a key.

Ernie O'Malley was finding it increasingly difficult to hide his activities from his parents, who queried the motives of the Irish Volunteers.

Ernie O'Malley was appointed second lieutenant in charge of the Coalisland district.

In May 1918, Collins sent Ernie O'Malley, who had "less than two years of informal training with the Irish Volunteers" to County Offaly.

Ernie O'Malley was instructed "to hold brigade officer elections and develop a fighting unit in an area seventy-five miles south-west of Dublin".

Ernie O'Malley arguably escaped capture or death when stopped by an RIC patrol in Philipstown, in the same county, and narrowly avoided having to draw a concealed pistol.

Ernie O'Malley crossed again to Roscommon and went to ground in the mountains.

Ernie O'Malley took responsibility for organising over a dozen areas of the country from 1918 to 1921, even the remote Galway island of Inisheer.

In visiting many parts of Ireland, both by bicycle and on foot, Ernie O'Malley carried much of what he owned, some 60 lb.

In mid-1919, Ernie O'Malley found himself in trouble with Collins for administering the new oath of allegiance to the Irish Republic to a company of IRA men in Santry, County Dublin.

In February 1920, Eoin O'Duffy and Ernie O'Malley led an IRA attack on the RIC barracks in Ballytrain, County Monaghan.

Ernie O'Malley participated actively in attacks on three RIC barracks: Hollyford, Drangan and Rearcross.

Ernie O'Malley had his hands burnt by a paraffin fire on the roof of Hollyford barracks; had the wind not changed direction at the very last second at Drangan, he would likely have been burnt alive; and he was wounded by shots fired upwards towards the roof by the policemen inside Rearcross barracks.

Ernie O'Malley was taken prisoner by Auxiliaries in the home of local IRA commandant James O'Hanrahan at Inistioge, County Kilkenny, on the morning of 9 December 1920.

Ernie O'Malley had been planning an attack on the Auxiliary barracks at Woodstock House, an important base in the south-east of the county that he knew to be well guarded.

Ernie O'Malley had been given an automatic Webley revolver; however, he was still unfamiliar with this new weapon and could not draw it in time.

Ernie O'Malley had displayed an uncharacteristic lack of care regarding O'Hanrahan's house being a likely British raiding target.

Much to Ernie O'Malley's disgust, seized were notebooks containing the names of members of the 7th West Kilkenny Brigade, all of whom were subsequently detained.

Ernie O'Malley endured a mixture of good treatment and violence from his various captors.

Ernie O'Malley was held under the name of "Stuart", as recorded by the British.

That flat had been used by Michael Collins, some of whose papers were captured, while Ernie O'Malley had documents in a separate room.

The seizure of Ernie O'Malley's papers led to a new name of interest to the British.

The IRA leadership feared Ernie O'Malley could be executed, for he was one of a number of men regarded as "notorious murderers".

In spring 1921 Ernie O'Malley chaired a stormy meeting near Mallow at which he advised senior Cork figures that GHQ had ordered the formation of the First Southern Division, in Munster.

Ernie O'Malley was summoned to a meeting in Dublin with the President of the Irish Republic Eamon de Valera, Collins and Mulcahy, where he was placed in command of the IRA's Second Southern Division, in Munster, ahead of more senior commanders in that province.

Ernie O'Malley felt that while the British had control of the cities and towns, the IRA had free rein over the countryside.

Ernie O'Malley was suspicious of the truce, but he used this time to work and strengthen his division, which saw visits from senior GHQ staff.

All in all, Ernie O'Malley felt that the IRA was still preparing for war.

Ernie O'Malley opposed the Anglo-Irish Treaty on the grounds that any settlement falling short of an independent Irish Republic, particularly a settlement backed up by British threats of restarting hostilities, was unacceptable.

Ernie O'Malley offered his resignation as officer commanding the Second Southern Division.

Ernie O'Malley is described as acting at that period as one of a number of "virtual warlords in their own areas".

Around this time Ernie O'Malley, who had refused to attend staff meetings at GHQ, ignored an order to attend a court martial in Dublin.

Ernie O'Malley was party to early meetings of what became known as the republican "acting military council".

Ernie O'Malley repudiated any efforts at compromise with the pro-treaty side, made by some opponents of the treaty.

Ernie O'Malley considered these as an attempt to create a wedge between the Four Courts garrison and the majority of republicans led by Lynch.

On 10 July 1922, Ernie O'Malley was made acting assistant chief of staff and was later appointed to the IRA army council.

Ernie O'Malley was appointed as head of the Eastern and Northern Command, covering the provinces of Ulster and Leinster.

Ernie O'Malley was disenchanted with being placed over areas he did not know well, instead of going to the west or south where his fighting experience would be put to much better use.

In September 1922, Ernie O'Malley pressed Lynch to implement Liam Mellows' proposed 10-Point Programme for the IRA, which would have seen it adopt communist policies in an attempt to secure support from left-wing elements in Ireland.

However, even if Ernie O'Malley thought highly of Mellows, there is nothing in his civil war-focused writings to indicate that he supported the Communist thrust of Mellows' programme.

Ernie O'Malley joined Frank Aiken and Padraig O Cuinn for a planned assault on Free State positions in Dundalk.

Ernie O'Malley was forced to live a clandestine existence in Dublin city, where he had to build up a new headquarters command staff.

Todd Andrews recorded that Ernie O'Malley hated being shut up in Dublin and would have excelled as a field commander.

Ernie O'Malley believed that Lynch's strategy of holding a defensive line in the south and locating GHQ in County Cork made no sense: a concerted attack on Dublin should have been an early priority.

Ernie O'Malley expressed the view that, to win the war, guerrilla tactics were insufficient.

Ernie O'Malley told Lynch that the destruction of communications, unless part of an immediate military operation, was folly, as it discouraged a fighting spirit.

On 4 November 1922, Ernie O'Malley was captured after a shoot-out with Free State soldiers at the family home of Nell O'Rahilly Humphreys, 36 Ailesbury Road, in the Donnybrook area of Dublin, which had been his headquarters for six weeks.

Ernie O'Malley was severely wounded in the incident, being hit over nine times.

Ernie O'Malley was kept in Portobello military hospital, where Free State army chief of staff Sean MacMahon visited him in a private capacity.

Ernie O'Malley was too ill to recognise the enemy general but learnt later that MacMahon had expressed a hope that Ernie O'Malley would not die.

Still severely affected by his wounds, Ernie O'Malley was transferred from Portobello to Mountjoy Prison hospital on 23 December 1922.

Ernie O'Malley believed that the authorities were waiting for him to recover sufficiently for an "elaborate trial" to take place, a scenario in which he would refuse to recognise the court.

Ernie O'Malley even wrote what he thought would be his final letter to Lynch.

Ernie O'Malley's most important external contact from prison was his friend the American-born Irish nationalist Molly Childers, wife of Erskine who was executed soon after Ernie O'Malley's arrest.

Ernie O'Malley was transferred to St Bricin's military hospital, thence to Mountjoy Prison where at first he spent some time in the hospital wing.

Ernie O'Malley left the Curragh, along with Sean Russell, on 17 July 1924, well over a year after the end of hostilities.

Ernie O'Malley was one of a sub-committee of five appointed to act as an army council to the executive.

Ernie O'Malley proposed a motion, passed unanimously, that IRA members must refuse to recognise courts in the Free State or Six Counties for charges relating to actions committed during the war or to political activities since then.

Ernie O'Malley stayed with Sinn Fein and did not join Fianna Fail in 1926, nor did he contest the June 1927 general election.

Ernie O'Malley left Ireland in February 1925 and spent 18 months travelling in Europe and Morocco to improve his health.

Ernie O'Malley used the alias 'Cecil Edward Smyth-Howard' and secured a British passport in that name.

Sean MacBride, then living in Paris, was made aware that Ernie O'Malley was known to French intelligence as a "chief military adviser to Colonel Macia", who was then in exile in Paris.

Ernie O'Malley likewise appears to have liaised with Basque nationalists around this same period, as they were planning a rebellion in tandem with that of the Catalans.

Ernie O'Malley was one of two Irish republicans, the other being Ambrose Victor Martin, to have cooperated with the Basque and Catalan nationalists resident in Paris, then exiled from the Spanish dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera.

Peadar O'Donnell stated that the IRA Army Council had given the go-ahead for Ernie O'Malley to speak to the Catalan separatists.

Ernie O'Malley returned to University College Dublin to continue his medical studies in October 1926, but these did not progress well.

Ernie O'Malley was heavily involved in the university hill-walking club and its literary and historical societies; along with literary friends, he founded the college Dramatic Society in spring 1928.

Ernie O'Malley left Ireland again in October 1928 without graduating.

Ernie O'Malley considered a newspaper that would articulate the anti-treaty position an important development.

Ernie O'Malley spent the next few years based in New Mexico, Mexico and New York.

Ernie O'Malley lived among the literary and artistic community there and close to the Native American pueblo of Taos.

Ernie O'Malley began work on his account of his military experiences that would later become On Another Man's Wound.

From late 1931 to June 1932, Ernie O'Malley worked in Taos as a tutor to the children of Helen Golden, widow of leading New York Irish nationalist Peter Golden; when she was hospitalised in early 1932, Ernie O'Malley looked after the children.

Hooker and Ernie O'Malley devoted themselves to the arts: she was involved in sculpture, photography and theatre, while he pursued a career in history and the arts as a writer.

Not long after his return to Ireland Ernie O'Malley became a member of the Royal Society of Antiquities of Ireland to further his interest in folklore.

Ernie O'Malley got to know the members of his family again, many of whom had distinguished careers during and after the war.

In summer 1945, Helen Ernie O'Malley went to America for six months to see her family and thereafter began to spend more time away from her husband and children.

Ernie O'Malley flew them to the States to live with her.

Ernie O'Malley's work was mostly complete, in notebook form, by autumn 1950, though it continued on and off until early 1954.

In 1951, Ernie O'Malley acted as a special adviser to John Ford on the set of The Quiet Man and the two became firm friends.

Ernie O'Malley's main weakness was a heart condition that started in childhood.

Ernie O'Malley died at 9.20 am on Monday 25 March 1957 at his sister Kaye's home in Howth.

Ernie O'Malley was fortunate, Ireland was fortunate in his being born into a period of Irish history where his special gifts, his soldierly qualities could be used to the greatest effect.

Ernie O'Malley remains an important figure in a "fractious period" of 20th-century Irish history.

Roy Foster observed: "What remains striking about Ernie O'Malley's legacy is not only his creation of one of the most remarkable memoirs in Irish literary history, but the story of the journey of a deeply original and powerful intelligence, coping with the fallout of an extraordinary youth and a saddened middle age".

Ernie O'Malley firmly believed that Ireland, having been dominated by an occupying power for so long, deserved to rule itself.

Ernie O'Malley contributed significantly to making IRA volunteers, often poorly armed, into a formidable guerrilla force.

Tom Barry, who was passed over for the divisional command given to Ernie O'Malley, felt that the latter paid too much heed to the military manual.

Todd Andrews stated that Ernie O'Malley had "taken part in more attacks on British soldiers, Black and Tans and RIC than any other IRA men in Ireland"; yet while admired, he was not generally liked.

Ernie O'Malley was uncomfortable with being addressed as "General" once he ceased being a soldier.

One author claims that Ernie O'Malley, in writing in The Singing Flame about nationalist defeats of old, the failure to defeat the Free State feeling as raw to republicans as any previous reverse and a fondness amongst his fellow captives for old ballads, was likening the departure of republicans from Ireland to the Flight of the Wild Geese; however, Ernie O'Malley did not use that specific term.

Ernie O'Malley's work filled a gap the historiography of the Irish revolutionary period that mostly overlooked the activities of local leaders and their men.

Ernie O'Malley's memoirs are the main inspiration behind the Ken Loach 2006 film The Wind that Shakes the Barley and the character of Damien Donovan is based loosely on O'Malley.

In 1928, in a letter to fellow republican Sheila Humphreys, Ernie O'Malley explained his attitude to writing:.

Ernie O'Malley's most celebrated writings are On Another Man's Wound, a memoir of the Irish War of Independence, and its sequel, The Singing Flame, a continuing memoir of his involvement in the Irish Civil War.

In 2012, a series entitled The Men Will Talk to Me: Ernie O'Malley's Interviews was initiated and has the interviews he made in Kerry, Galway, Mayo, Clare, Cork and with the Northern Divisions.

Ernie O'Malley wrote and published some poetry in Poetry magazine in 1935 and 1936, and in the Dubliner Magazine in 1935.

In late 1946, Ernie O'Malley explained the recent revolutionary conflict in Ireland and the context of Irish neutrality during WWII for a French audience.

Ernie O'Malley wrote many as yet unpublished works of poetry, sketches, essays and his 1926 experiences in the Pyrenees.