1.

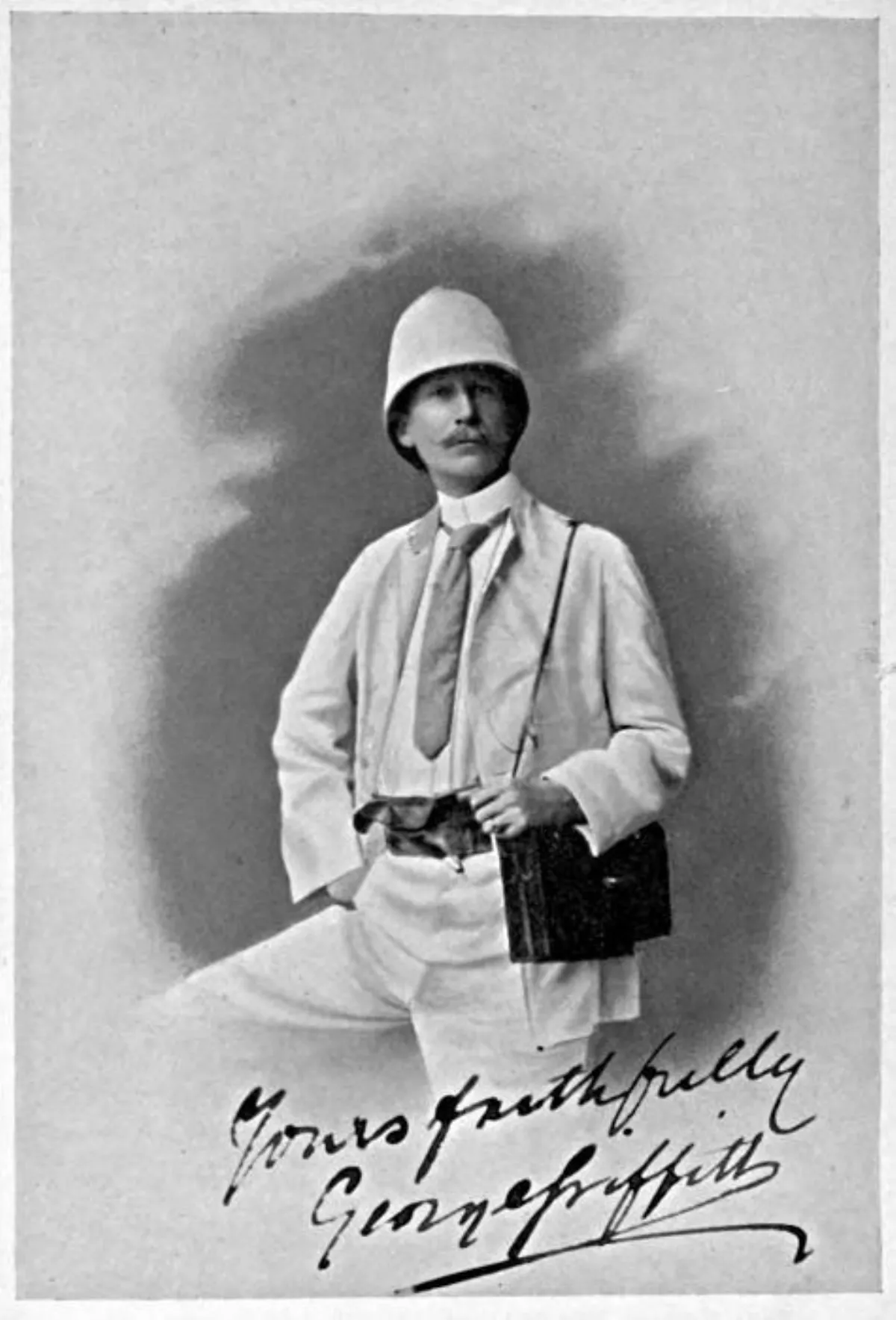

1. George Griffith then worked as a teacher for ten years before pursuing a career in writing.

1.

1. George Griffith then worked as a teacher for ten years before pursuing a career in writing.

George Griffith made his literary breakthrough with his debut novel The Angel of the Revolution, which was serialized in Pearson's Weekly before being published in book format.

George Griffith signed a contract of exclusivity with Pearson and followed it up with the likewise successful sequel Olga Romanoff.

George Griffith was highly active as a writer throughout the 1890s, producing numerous serials and short stories for Pearson's various publications.

George Griffith wrote non-fiction for Pearson and went on various travel assignments.

George Griffith's last outright success was A Honeymoon in Space, and he parted ways with Pearson shortly thereafter.

George Griffith was both successful and influential as a writer at the peak of his career, but he has since descended into obscurity.

George Griffith regularly incorporated his personal viewpoints into his fiction, and anti-American sentiments expressed in this way ensured that he never established a readership in the United States as publishers there would not print his works.

George Griffith was irreligious and in his youth advocated fiercely for secularism.

Politically, George Griffith was early an outspoken socialist, though he is believed to have gradually shifted towards more right-leaning sympathies later in his life.

George Griffith's parents were the clergyman George Alfred Jones and Jeanette Henry Capinster Jones.

George Griffith spent considerable time exploring his father's extensive library, which was filled with the works of authors who would later serve as Griffith's literary influences, including Walter Scott and Jules Verne.

George Griffith deserted his ship in Melbourne after 11 weeks at sea, having found the experience highly instructive but the corporal punishment in particular gruelling.

George Griffith started working as a schoolmaster in 1877, six months after his return to England, teaching English at the preparatory school Worthing College in Sussex.

George Griffith left Worthing to study at a university in Germany, returning a year later to teach at Brighton.

George Griffith continued to study at nights to get the necessary teaching diplomas for a career in education.

George Griffith started his writing career while at Brighton, writing for local papers among others.

George Griffith then took a job teaching at Bolton Grammar School in 1883, and while there published his first two books: the poetry collections Poems and The Dying Faith, both published under his pen name Lara.

George Griffith passed the College of Preceptors exam the same year, thus completing his formal education in teaching, and promptly left that line of work in favour of pursuing a career in writing.

George Griffith worked his way up to become the magazine's editor, and eventually took over as owner.

At the time, George Griffith was highly politically active, advocating for socialism and secularism.

George Griffith decided against hiring a lawyer, opting instead to represent himself, and ended up losing the case which led to the paper going out of business.

George Griffith was thus unemployed, and while he continued to pen political and religious pamphlets for a while as a freelancer, it was not enough to provide a living.

George Griffith got a job at the newly founded Pearson's Weekly in 1890, initially tasked by the editor Peter Keary with writing addresses on envelopes for the magazine's competitions.

George Griffith made a good impression on Keary through his skill as a conversationalist, largely owing to his background travelling the world, and was promoted to columnist.

George Griffith carried on in this capacity for the rest of the decade.

George Griffith brought in a synopsis the following day, and got the assignment.

The book version was likewise a success, receiving rave reviews and becoming a best-seller; it was printed in six editions within a year and at least eleven editions in total, and a review in The Pelican declared George Griffith to be "a second Jules Verne".

Pearson responded by signing a contract of exclusivity with George Griffith and providing him with a secretary for dictation.

George Griffith was then the most popular and commercially successful science fiction author in the country.

None of George Griffith's books were published in the US until more than half a century after his death, and it would not be until 1902 that the first and only serial of his was published in a US magazine.

Parallel to the serialization of The Syren of the Skies, George Griffith carried out a publicity stunt on behalf of Pearson by travelling around the world in as little time as possible, emulating the fictional journey in Verne's Around the World in Eighty Days.

George Griffith accomplished the feat in 65 days, starting on 12 March 1894 and finishing on 16 May The tale of his journey was told in Pearson's Weekly in 14 parts between 2 June and 1 September 1894, bearing the title "How I Broke the Record Round the World".

Pearson tasked George Griffith with writing a new future-war serial to boost sales of Short Stories, a magazine he had acquired in mid-1893.

Large portions of the South American continent were undergoing political turmoil at the time, and George Griffith covered the various revolutionary factions in harshly critical terms, viewing them as aspiring oppressors.

George Griffith later claimed to have found the source of the Amazon River; Moskowitz speculates that this could have happened during this assignment.

George Griffith launched a new all-serial magazine called Pearson's Story Teller on 9 October 1895, for which Griffith wrote the historical adventure story The Knights of the White Rose.

In 1896, George Griffith went on another travel assignment for Pearson, this time to Southern Africa.

George Griffith had been asked to assess the political situation and write about possible future developments, and was given free rein to travel the region to that end.

George Griffith thus travelled to the British colonies of Cape Colony and Natal, the British Bechuanaland Protectorate, the Boer republics of Transvaal and the Orange Free State, and Portuguese Mozambique.

George Griffith interviewed among others Transvaal President Paul Kruger, and came to the conclusion that a war between the British and the Boers was on the horizon.

George Griffith nevertheless continued his prolific writing, with his serial The Gold Magnet appearing in Short Stories starting on 16 October 1897 and the short story "The Great Crellin Comet" appearing in the special Christmas issue of Pearson's Weekly the same year.

George Griffith next wrote The Virgin of the Sun, a fictionalized but non-fantastical account of Francisco Pizarro's conquest of Peru in the 1530s, inspired by his South American journey a few years prior.

George Griffith travelled abroad in late 1899, this time to Australia, and unusually at his own expense rather than as part of an assignment.

George Griffith's last piece of fiction writing published by Pearson was "The Raid of Le Vengeur" in Pearson's Magazine in February 1901 and his last non-fiction was an essay in Pearson's Magazine in November 1902.

George Griffith nevertheless continued writing prolifically, though he did not meet with much success.

The twilight years of George Griffith's career were marked by a return to the future war genre, a great quantity of such stories being produced towards the end of his life.

Virtually to his dying gasp, George Griffith continued to dictate war after war, each to end all wars.

George Griffith continued to write in spite of his worsening condition.

George Griffith died at his home in Port Erin on 4 June 1906, at the age of 48.

Moskowitz notes that malaria can have a similar clinical presentation; George Griffith had contracted malaria in Hong Kong, and the literary biographer Peter Berresford Ellis writes that it at least contributed to his deteriorating condition.

Stableford, who similarly concludes that George Griffith likely started consuming alcohol excessively no later than the mid-1890s, additionally points to what he describes as "a seemingly alcoholic quality about the garrulous fluency of his later works".

Bleiler, in the 1990 reference work Science-Fiction: The Early Years, comments that George Griffith may be considered the first professional English-language science fiction author.

George Griffith danced to the beat of the nearest drummer.

George Griffith is noted for predicting technologies that had not yet been invented; among these are heavier-than-air aircraft, radar, sonar, and air-to-surface missiles.

George Griffith is similarly credited with anticipating developments in warfare, in particular the coming importance of aerial warfare, but in terms of military tactics including the use of poison gas.

George Griffith is recognized as having correctly predicted the outbreak of the Boer War, though Moskowitz comments that this did not require particularly keen foresight.

Ellis writes that while George Griffith's repeated motif of a war between Britain and the US never came to pass, it has since been revealed that both countries did in fact plan for such an eventuality up until the lead-up to World War II.

McNabb similarly opines that "what George Griffith lacked in literary style, he made up for in imaginative and exuberant story telling", comparing him in this regard to Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Moskowitz and Ellis both commend George Griffith for portraying women as equals to men, commenting that he was ahead of his contemporaries on that point.

Barbara Arnett Melchiori, by contrast, finds George Griffith to portray women as little more than the private property of men.

Scholars on Wells, by contrast, usually do not consider George Griffith to have been an important influence.

George Griffith was irreligious, and in his youth he wrote for the freethinker magazine Secular Review.

Stableford comments that being a freethinker whose father was a clergyman was a background George Griffith shared with many other scientific romance authors.

Moskowitz further writes that George Griffith appears to have taken up an interest in the occult in the later years of his life.

George Griffith incorporated his political views into his fiction, and much has been written about what can be gleaned from his writings about his viewpoints.

Melchiori writes that there are a number of inconsistencies in his debut novel The Angel of the Revolution which indicate to her that George Griffith "had by no means fully absorbed the doctrine that he was preaching".

Stableford writes that George Griffith's works reveal a successive shift to increasingly right-leaning sympathies, with anarchists being portrayed positively alongside socialists in his very earliest stories but quickly rejected afterwards, and the socialists in turn being displaced by capitalists in the later works.

Wood writes that "George Griffith's fiction celebrates social conservatism and British global predominance, preaching the maintenance of this status quo".

George Griffith writes that Griffith's works reinforced then-common beliefs among his readers about their own inherent superiority.