1.

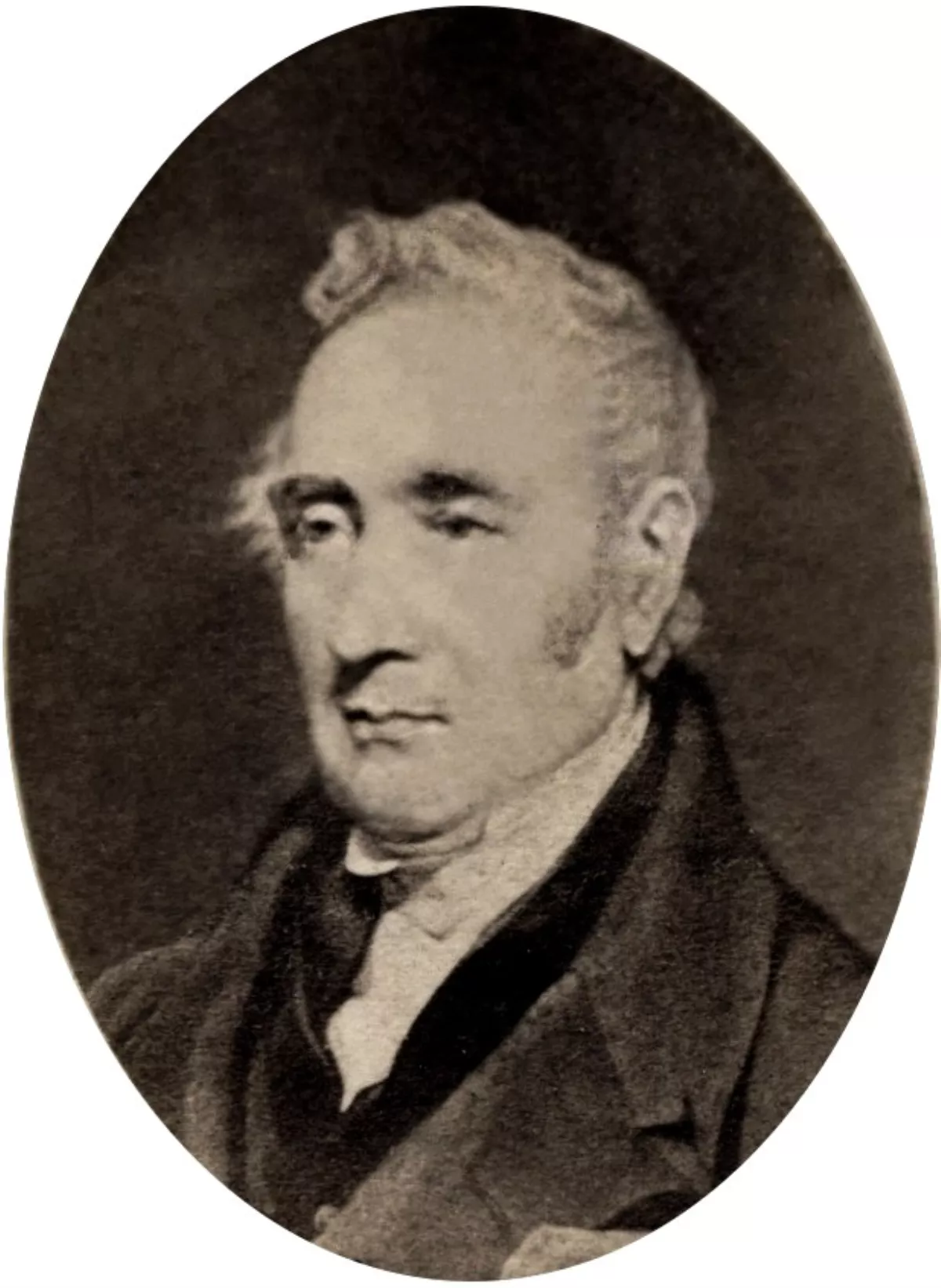

1. George Stephenson was an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer during the Industrial Revolution.

1.

1. George Stephenson was an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer during the Industrial Revolution.

George Stephenson's chosen rail gauge, sometimes called "Stephenson gauge", was the basis for the.

George Stephenson built the first public inter-city railway line in the world to use locomotives, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, which opened in 1830.

George Stephenson was the second child of Robert and Mabel Stephenson, neither of whom could read or write.

At 17, George Stephenson became an engineman at Water Row Pit in Newburn nearby.

George Stephenson made shoes and mended clocks to supplement his income.

George Stephenson was buried in the same churchyard as their daughter on 16 May 1806, though the location of the grave is lost.

George Stephenson decided to find work in Scotland and left Robert with a local woman while he went to work in Montrose.

George Stephenson moved back into a cottage at West Moor and his unmarried sister Eleanor moved in to look after Robert.

In 1811 the pumping engine at High Pit, Killingworth was not working properly and George Stephenson offered to improve it.

George Stephenson did so with such success that he was promoted to enginewright for the collieries at Killingworth, responsible for maintaining and repairing all the colliery engines.

In 1815, aware of the explosions often caused in mines by naked flames, George Stephenson began to experiment with a safety lamp that would burn in a gaseous atmosphere without causing an explosion.

George Stephenson, having come from the North-East, spoke with a broad Northumberland accent and not the 'Language of Parliament,' which made him seem lowly.

In 1833 a House of Commons committee found that George Stephenson had equal claim to having invented the safety lamp.

Davy went to his grave believing that George Stephenson had stolen his idea.

The George Stephenson lamp was used almost exclusively in North East England, whereas the Davy lamp was used everywhere else.

George Stephenson made reference to an incident at Oaks Colliery in Barnsley where both lamps were in use.

George Stephenson designed his first locomotive in 1814, a travelling engine designed for hauling coal on the Killingworth wagonway named Blucher after the Prussian general Gebhard Leberecht von Blucher.

Blucher was modelled on Matthew Murray's locomotive Willington, which George studied at Kenton and Coxlodge colliery on Tyneside, and was constructed in the colliery workshop behind Stephenson's home, Dial Cottage, on Great Lime Road.

Altogether, George Stephenson is said to have produced 16 locomotives at Killingworth, although it has not proved possible to produce a convincing list of all 16.

Together with William Losh, George Stephenson improved the design of cast-iron edge rails to reduce breakage; rails were briefly made by Losh, Wilson and Bell at their Walker ironworks.

George Stephenson experimented with a steam spring, but soon followed the practice of 'distributing' weight by using a number of wheels or bogies.

George Stephenson was hired to build the eight-mile Hetton colliery railway in 1820.

George Stephenson used a combination of gravity on downward inclines and locomotives for level and upward stretches.

The original plan was to use horses to draw coal carts on metal rails, but after company director Edward Pease met George Stephenson, he agreed to change the plans.

George Stephenson surveyed the line in 1821, and assisted by his 18-year-old son Robert, construction began the same year.

Pease and George Stephenson had jointly established a company in Newcastle to manufacture locomotives.

George Stephenson had ascertained by experiments at Killingworth that half the power of the locomotive was consumed by a gradient as little as 1 in 260.

George Stephenson concluded that railways should be kept as level as possible.

George Stephenson used this knowledge while working on the Bolton and Leigh Railway, and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, executing a series of difficult cuttings, embankments and stone viaducts to level their routes.

The revised alignment presented the problem of crossing Chat Moss, an apparently bottomless peat bog, which George Stephenson overcame by unusual means, effectively floating the line across it.

George Stephenson's entry was Rocket, and its performance in winning the contest made it famous.

The parade was led by Northumbrian driven by George Stephenson, and included Phoenix driven by his son Robert, North Star driven by his brother Robert and Rocket driven by assistant engineer Joseph Locke.

George Stephenson evacuated the injured Huskisson to Eccles with a train, but he died from his injuries.

George Stephenson became famous, and was offered the position of chief engineer for a wide variety of other railways.

George Stephenson moved to the parish of Alton Grange in Leicestershire in 1830, originally to consult on the Leicester and Swannington Railway, a line primarily proposed to take coal from the western coal fields of the county to Leicester.

George Stephenson realising the financial potential of the site, given its proximity to the proposed rail link and the fact that the manufacturing town of Leicester was then being supplied coal by canal from Derbyshire, bought the estate.

George Stephenson remained at Alton Grange until 1838 before moving to Tapton House in Derbyshire.

For example, rather than the West Coast Main Line taking the direct route favoured by Joseph Locke over Shap between Lancaster and Carlisle, George Stephenson was in favour of a longer sea-level route via Ulverston and Whitehaven.

George Stephenson tended to be more casual in estimating costs and paperwork in general.

George Stephenson worked with Joseph Locke on the Grand Junction Railway with half of the line allocated to each man.

George Stephenson's estimates and organising ability proved inferior to those of Locke and the board's dissatisfaction led to George Stephenson's resignation causing a rift between them which was never healed.

George Stephenson worked on the North Midland line from Derby to Leeds, the York and North Midland line from Normanton to York, the Manchester and Leeds, the Birmingham and Derby, the Sheffield and Rotherham among many others.

George Stephenson became a reassuring name rather than a cutting-edge technical adviser.

George Stephenson was the first president of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers on its formation in 1847.

George Stephenson first courted Elizabeth Hindmarsh, a farmer's daughter from Black Callerton, whom he met secretly in her orchard.

George Stephenson's father refused marriage because of Stephenson's lowly status as a miner.

George Stephenson next paid attention to Anne Henderson where he lodged with her family, but she rejected him and he transferred his attentions to her sister Frances, who was nine years his senior.

On 29 March 1820, George Stephenson married Betty Hindmarsh at Newburn.

On 11 January 1848, at St Chad's Church in Shrewsbury, Shropshire, George Stephenson married for the third time, to Ellen Gregory, another farmer's daughter originally from Bakewell in Derbyshire, who had been his housekeeper.

Seven months after his wedding, George Stephenson contracted pleurisy and died, aged 67, at noon on Saturday 12 August 1848 at Tapton House in Chesterfield, Derbyshire.

George Stephenson was buried at Holy Trinity Church, Chesterfield, alongside his second wife.

George Stephenson was a keen gardener throughout his life; during his last years at Tapton House, he built hothouses in the estate gardens, growing exotic fruits and vegetables in a 'not too friendly' rivalry with Joseph Paxton, head gardener at nearby Chatsworth House, twice beating the master of the craft.

George Stephenson's son Robert was born on 16 October 1803.

Robert George Stephenson expanded on the work of his father and became a major railway engineer himself.

George Stephenson's daughter was born in 1805 but died within weeks of her birth.

Descendants of the wider George Stephenson family continue to live in Wylam today.

George Stephenson was farsighted in realising that the individual lines being built would eventually be joined, and would need to have the same gauge.

The Band of Hope were selling biographies of George Stephenson in 1859 at a penny a sheet, and at one point there was a suggestion to move George Stephenson's body to Westminster Abbey.

The centenary of George Stephenson's birth was celebrated in 1881 at Crystal Palace by 15,000 people, and it was George Stephenson who was featured on the reverse of the Series E five pound note issued by the Bank of England between 1990 and 2003.

George Stephenson's Birthplace is an 18th-century historic house museum in the village of Wylam, and is operated by the National Trust.

Chesterfield Museum in Chesterfield, Derbyshire, has a gallery of George Stephenson memorabilia, including straight thick glass tubes he invented for growing straight cucumbers.

George Stephenson College, founded in 2001 on the Durham University's Queen's Campus in Stockton-on-Tees, is named after him.

George Stephenson's face is shown alongside an engraving of the Rocket steam engine and the Skerne Bridge on the Stockton to Darlington Railway.

George Stephenson's profile is carved in the facade of Lisbon's Victorian railway station.

George Stephenson was portrayed by actor Gawn Grainger on television in the 1985 Doctor Who serial The Mark of the Rani.