1.

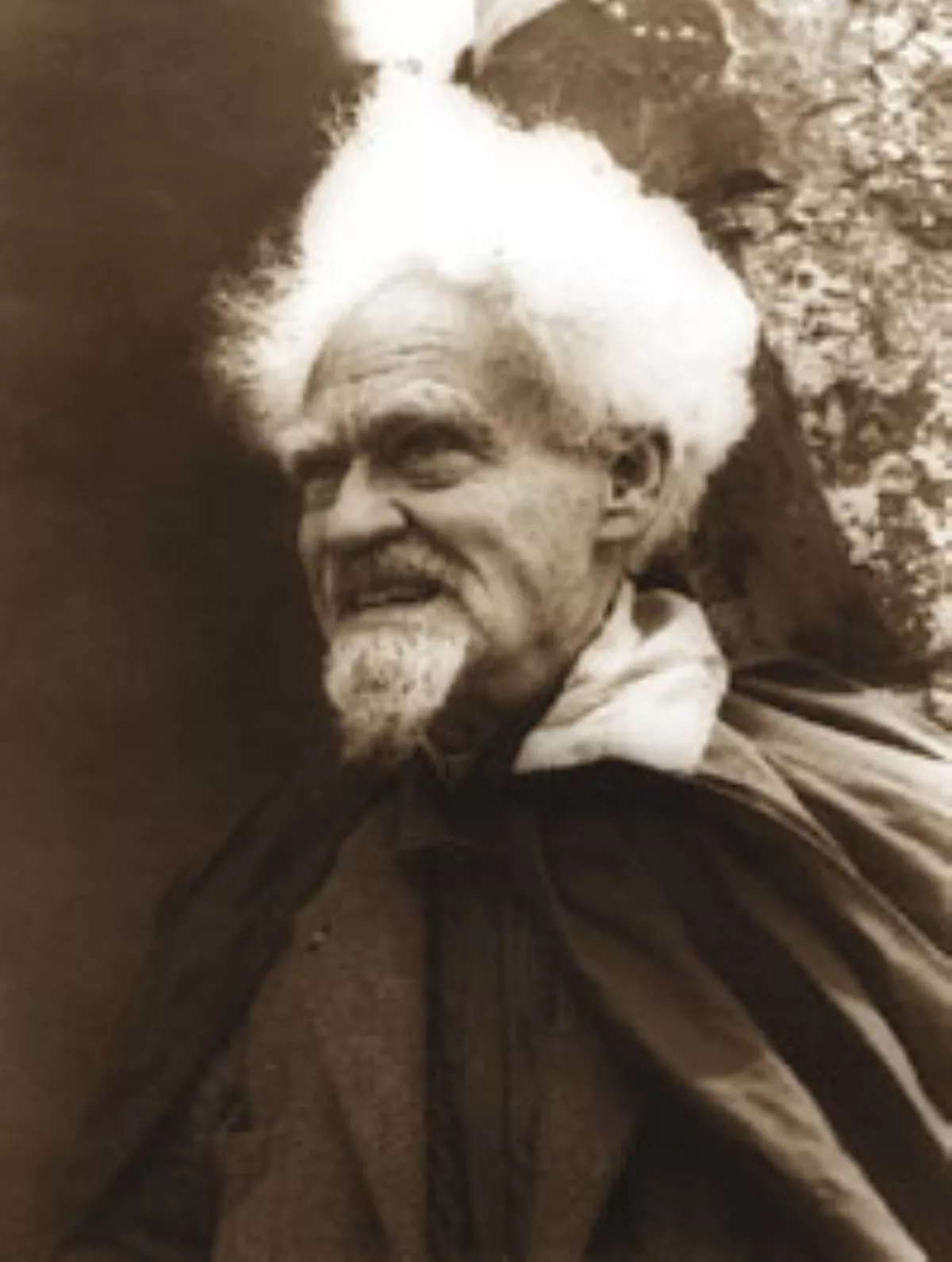

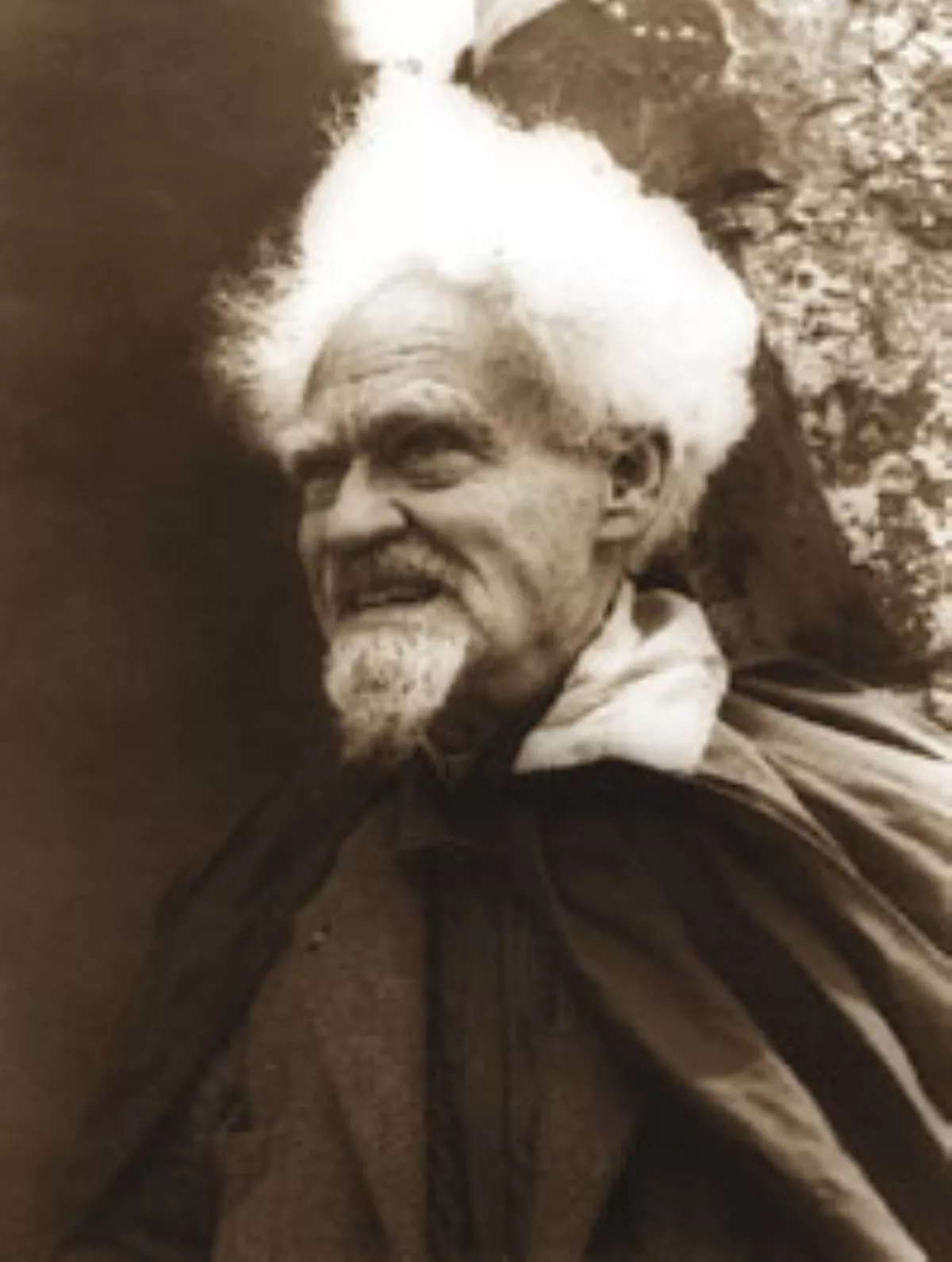

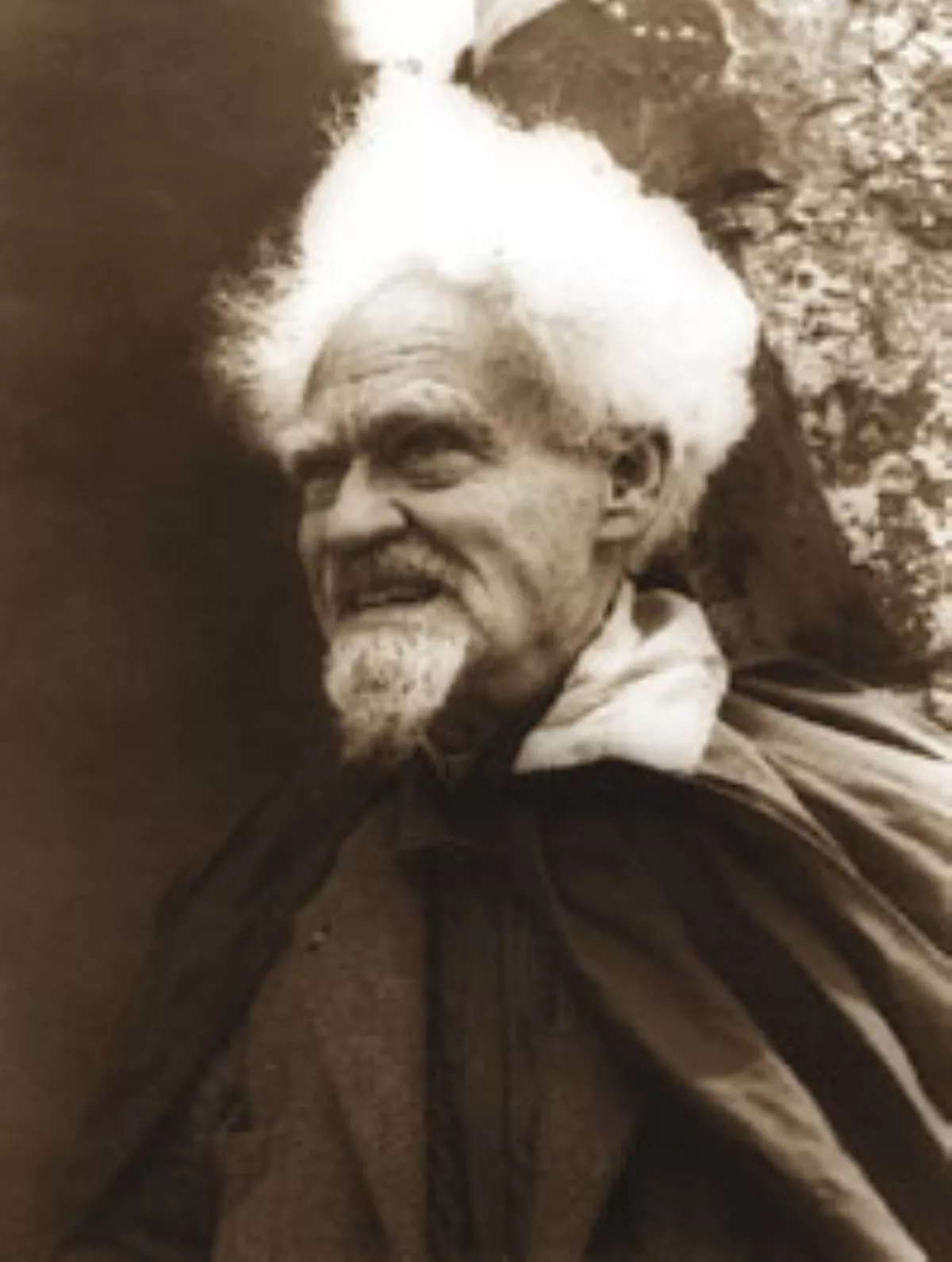

1. Gerald Gardner was instrumental in bringing the modern pagan religion of Wicca to public attention, writing some of its definitive religious texts and founding the tradition of Gardnerian Wicca.

1.

1. Gerald Gardner was instrumental in bringing the modern pagan religion of Wicca to public attention, writing some of its definitive religious texts and founding the tradition of Gardnerian Wicca.

Gerald Gardner supplemented the coven's rituals with ideas borrowed from Freemasonry, ceremonial magic, and the writings of Aleister Crowley to form the Gardnerian tradition of Wicca.

In 1876 the family moved into one of the neighbouring houses, Ingle Lodge, and it was here that the couple's third son, Gerald Brosseau Gardner, was born on Friday 13 June 1884.

Gerald Gardner suffered with asthma from a young age, having particular difficulty in the cold Lancashire winters.

Gerald Gardner's nursemaid offered to take him to warmer climates abroad at his father's expense in the hope that this condition would not be so badly affected.

Gerald Gardner taught himself to read by looking at copies of The Strand Magazine but his writing betrayed his lack of formal schooling with eccentric spelling and grammar.

At his father's expense, Gerald Gardner trained as a "creeper", or trainee planter, learning all about the growing of tea; although he disliked the "dreary endlessness" of the work, he enjoyed being outdoors and near to the forests.

Gerald Gardner lived with the Elkingtons until 1904, when he moved into his own bungalow and began earning a living working on the Non Pareil tea estate below the Horton Plains.

Gerald Gardner spent much of his spare time hunting deer and trekking through the local forests, becoming acquainted with the Singhalese natives and taking a great interest in their Buddhist beliefs.

In December 1904, his parents and younger brother visited, with his father asking him to invest in a pioneering rubber plantation which Gerald Gardner was to manage; located near the village of Belihuloya, it was known as the Atlanta Estate, but allowed him a great deal of leisure time.

In 1907 Gerald Gardner returned to Britain for several months' leave, spending time with his family and joining the Legion of Frontiersmen, a militia founded to repel the threat of German invasion.

Gerald Gardner returned to Ceylon in late 1907 and settled down to the routine of managing the rubber plantation.

Gerald Gardner placed great importance on this new activity; In order to attend masonic meetings, he had to arrange a weekend's leave, walk 15 miles to the nearest railway station in Haputale, and then catch a train to the city.

Gerald Gardner entered into the second and third degrees of Freemasonry within the next month, but this enthusiasm seems to have waned, and he resigned the next year, probably because he intended to leave Ceylon.

That year, Gerald Gardner moved to British North Borneo, gaining employment as a rubber planter at the Mawo Estate at Membuket.

An amateur anthropologist, Gerald Gardner was fascinated by the indigenous way of life, particularly the local forms of weaponry such as the sumpitan.

Gerald Gardner was intrigued by the tattoos of the Dayaks and pictures of him in later life show large snake or dragon tattoos on his forearms, presumably obtained at this time.

Gerald Gardner was unhappy with the working conditions and the racist attitudes of his colleagues, and when he developed malaria he felt that this was the last straw; he left Borneo and moved to Singapore, in what was then known as the Straits Settlements, part of British Malaya.

Cornwall invited Gerald Gardner to make the Shahada, the Muslim confession of faith, which he did; it allowed him to gain the trust of locals, although he would never become a practising Muslim.

Cornwall was however an unorthodox Muslim, and his interest in local peoples included their magical and spiritual beliefs, to which he introduced Gerald Gardner, who took a particular interest in the kris, a ritual knife with magical uses.

In 1915, Gerald Gardner again joined a local volunteer militia, the Malay States Volunteer Rifles.

Gerald Gardner was keen to do more towards the war effort and in 1916 returned to Britain.

Gerald Gardner attempted to join the Royal Navy but was turned down due to ill health.

Gerald Gardner was working in the VAD when casualties came back from the Battle of the Somme and he was engaged in looking after patients and assisting in changing wound dressings.

Gerald Gardner soon had to give this up when his malaria returned, and so decided to return to Malaya in October 1916 because of the warmer climate.

Gerald Gardner continued to manage the rubber plantation but after the end of the war, commodity prices dropped and by 1921 it was difficult to make a profit.

Gerald Gardner returned again to Britain, in what later biographer Philip Heselton speculated might have been an unsuccessful attempt to ask his father for money.

In 1926 he was placed in charge of monitoring shops selling opium, noting regular irregularities and a thriving illegal trade in the controlled substance; believing opium to be essentially harmless, there is evidence indicating that Gerald Gardner probably took many bribes in this position, earning himself a small fortune.

Gerald Gardner's mother had died in 1920, but he had not returned to Britain on that occasion.

However, in 1927 his father became very ill with dementia, and Gerald Gardner decided to visit him.

On his return to Britain, Gerald Gardner began to investigate spiritualism and mediumship.

Gerald Gardner soon had several encounters which he attributed to spirits of deceased family members.

Gerald Gardner's first biographer Jack Bracelin reports that this was a watershed in Gardner's life, and that a previous academic interest in spiritualism and life after death thereafter became a matter of firm personal belief for him.

The very same evening after Gerald Gardner had met this medium, he met the woman he was to marry; Dorothea Frances Rosedale, known as Donna, a relation of his sister-in-law Edith.

Gerald Gardner asked her to marry him the next day and she agreed.

Gerald Gardner returned to his old interests in the anthropology of Malaya, witnessing the magical practices performed by the locals, and he readily accepted a belief in magic.

Gerald Gardner was not only interested in the anthropology of Malaya, but in its archaeology.

Gerald Gardner began excavations at the city of Johore Lama, alone and in secret, as the local Sultan considered archaeologists little better than grave-robbers.

Gerald Gardner went on to begin further excavations at the royal cemetery of Kota Tinggi, and the jungle city of Syong Penang.

Gerald Gardner's finds were displayed as an exhibit on the "Early History of Johore" at the National Museum of Singapore, and several beads that he had discovered suggested that trade went on between the Roman Empire and the Malays, presumably, Gardner thought, via India.

Gerald Gardner found gold coins originating from Johore and he published academic papers on both the beads and the coins.

Gerald Gardner was encouraged in this by the director of the Raffles Museum and by his election to Fellowship of the Royal Anthropological Institute in 1936.

En route back to London in 1932 Gerald Gardner stopped off in Egypt and, armed with a letter of introduction, joined Sir Flinders Petrie who was excavating the site of Tall al-Ajjul in Palestine.

Gerald Gardner befriended the archaeologist and practising Pagan Alexander Keiller, known for his excavations at Avebury, who would encourage Gardner to join in with the excavations at Hembury Hill in Devon, attended by Aileen Fox and Mary Leakey.

Gerald Gardner then took a train to Hangzhou in China, before continuing onto Shanghai; because of the ongoing Chinese Civil War, the train did not stop throughout the entire journey, something that annoyed the passengers.

In 1935, Gerald Gardner attended the Second Congress for Prehistoric Research in the Far East in Manila, Philippines, acquainting himself with several experts in the field.

Gerald Gardner wanted to stay in Malaya, but he conceded to his wife Donna, who insisted that they return to England.

Gerald Gardner proceeded straight to London, renting them a flat at 26 Charing Cross Road.

From Palestine, Gerald Gardner went to Turkey, Greece, Hungary, and Germany.

Gerald Gardner eventually reached England, but soon went on a visit to Denmark to attend a conference on weaponry at the Christiansborg Palace, Copenhagen, during which he gave a talk on the kris.

Hesitant at first, Gerald Gardner first attended an indoor nudist club, the Lotus League in Finchley, North London, where he made several new friends and felt that the nudity cured his ailment.

Back in London, in September 1937, Gerald Gardner applied for and received a Doctorate of Philosophy from the Meta Collegiate Extension of the National Electronic Institute, an organisation based in Nevada that was widely recognised by academic institutions as offering invalid academic degrees via post for a fee.

In Highcliffe, Gerald Gardner came across a building describing itself as the "First Rosicrucian Theatre in England".

Unperturbed and hoping to learn more of Rosicrucianism, Gerald Gardner joined the group in charge of running the theatre, the Rosicrucian Order Crotona Fellowship, and began attending meetings held in their local ashram.

Gerald Gardner facetiously asked if he was the Wandering Jew, much to the annoyance of Sullivan himself.

In 1939, Gerald Gardner joined the Folk-Lore Society; his first contribution to its journal Folk-Lore, appeared in the June 1939 issue and described a box of witchcraft relics that he believed had belonged to the 17th century "Witch-Finder General", Matthew Hopkins.

Gerald Gardner would join the Historical Association, being elected co-president of its Bournemouth and Christchurch branch in June 1944, following which he became a vocal supporter for the construction of a local museum for the Christchurch borough.

Gerald Gardner involved himself in preparations for the impending war, joining the Air Raid Precautions as a warden, where he soon rose to a position of local seniority, with his own house being assigned as the ARP post.

Gerald Gardner managed to circumvent this restriction by joining his local Home Guard in the capacity as armourer, which was officially classified as technical staff.

Gerald Gardner took a strong interest in the Home Guard, helping to arm his fellows from his own personal weaponry collection and personally manufacturing molotov cocktails.

Gerald Gardner only ever described one of their rituals in depth, and this was an event that he termed "Operation Cone of Power".

However, following the war, Gerald Gardner decided to return to London, moving into 47 Ridgemount Gardens, Bloomsbury in late 1944 or early 1945.

Gerald Gardner made a deal with Ward exchanging the cottage for Gerald Gardner's piece of land near to Famagusta in Cyprus.

Gerald Gardner took an interest in Druidry, joining the Ancient Druid Order and attending its annual Midsummer rituals at Stonehenge.

Gerald Gardner joined the Folk-Lore Society, being elected to their council in 1946, and that same year giving a talk on "Art Magic and Talismans".

Gerald Gardner met Crowley's successor, Karl Germer, in New York though Gardner would soon lose interest in leading the OT.

Gerald Gardner hoped to spread Wicca and described some of its practices in a fictional form as High Magic's Aid.

Gerald Gardner gained some of his first initiates, Barbara and Gilbert Vickers, who were initiated at some point between autumn 1949 and autumn 1950.

Gerald Gardner came into contact with Cecil Williamson, who was intent on opening his own museum devoted to witchcraft; the result would be the Folk-lore Centre of Superstition and Witchcraft, opened in Castletown on the Isle of Man in 1951.

In 1954, Gerald Gardner bought the museum from Williamson, who returned to England to form the rival Museum of Witchcraft, eventually settling it in Boscastle, Cornwall.

Gerald Gardner renamed his exhibition the Museum of Magic and Witchcraft and continued running it up until his death.

Gerald Gardner acquired a flat at 145 Holland Road, near Shepherd's Bush in West London, but nevertheless fled to warmer climates during the winter, where his asthma would not be so badly affected, for instance spending time in France, Italy, and the Gold Coast.

In 1952, Gerald Gardner had begun to correspond with a young woman named Doreen Valiente.

Gerald Gardner eventually requested initiation into the Craft, and though Gardner was hesitant at first, he agreed that they could meet during the winter at the home of Edith Woodford-Grimes.

Gerald Gardner soon rose to become the High Priestess of the coven and helped Gardner to revise his Book of Shadows, and attempting to cut out most of Crowley's influence.

In 1954, Gerald Gardner published a non-fiction book, Witchcraft Today, containing a preface by Margaret Murray, who had published her discredited theory of 'witchcraft' being a surviving pagan religion in her 1921 book, The Witch-Cult in Western Europe.

Alongside this book, Gerald Gardner began to increasingly court publicity, going so far as to invite the press to write articles about the religion.

Gerald Gardner continued courting publicity, despite the negative articles that many tabloids were producing, and believed that only through publicity could more people become interested in witchcraft, so preventing the "Old Religion", as he called it, from dying out.

In 1960, Gardner's official biography, entitled Gerald Gardner: Witch, was published.

In 1963, Gerald Gardner decided to go to Lebanon over the winter.

Gerald Gardner was buried in Tunisia, the ship's next port of call, and his funeral was attended only by the ship's captain.

Gerald Gardner had left parts of his inheritance to Patricia Crowther, Doreen Valiente, Lois Bourne and Jack Bracelin, the latter inheriting the Fiveacres Nudist Club and taking over as full-time High Priest of the Bricket Wood coven.

Gerald Gardner discovered that the cemetery he was interred in was to be redeveloped, and so she raised enough money for his body to be moved to another cemetery in Tunis, where it currently remains.

Gerald Gardner only married once, to Donna, and several who knew him have said that he was devoted to her.

The author Philip Heselton, who largely researched Wicca's origins, came to the conclusion that Gerald Gardner had held a long-term affair with Dafo, a theory expanded upon by Adrian Bott.

Gerald Gardner had several tattoos on his body, depicting magical symbols such as a snake, dragon, anchor and dagger.

Lamond thought that Gerald Gardner was "surprisingly lacking in charisma" for someone at the forefront of a religious movement.

Gerald Gardner was a supporter of the centre-right Conservative Party, and for several years had been a member of the Highcliffe Conservative Association, as well as being an avid reader of the pro-Conservative newspaper, The Daily Telegraph.

Valiente reports that Gerald Gardner responded with a set of Wiccan laws of his own, which he claimed were original, but others suspected he had made up on the spot.