1.

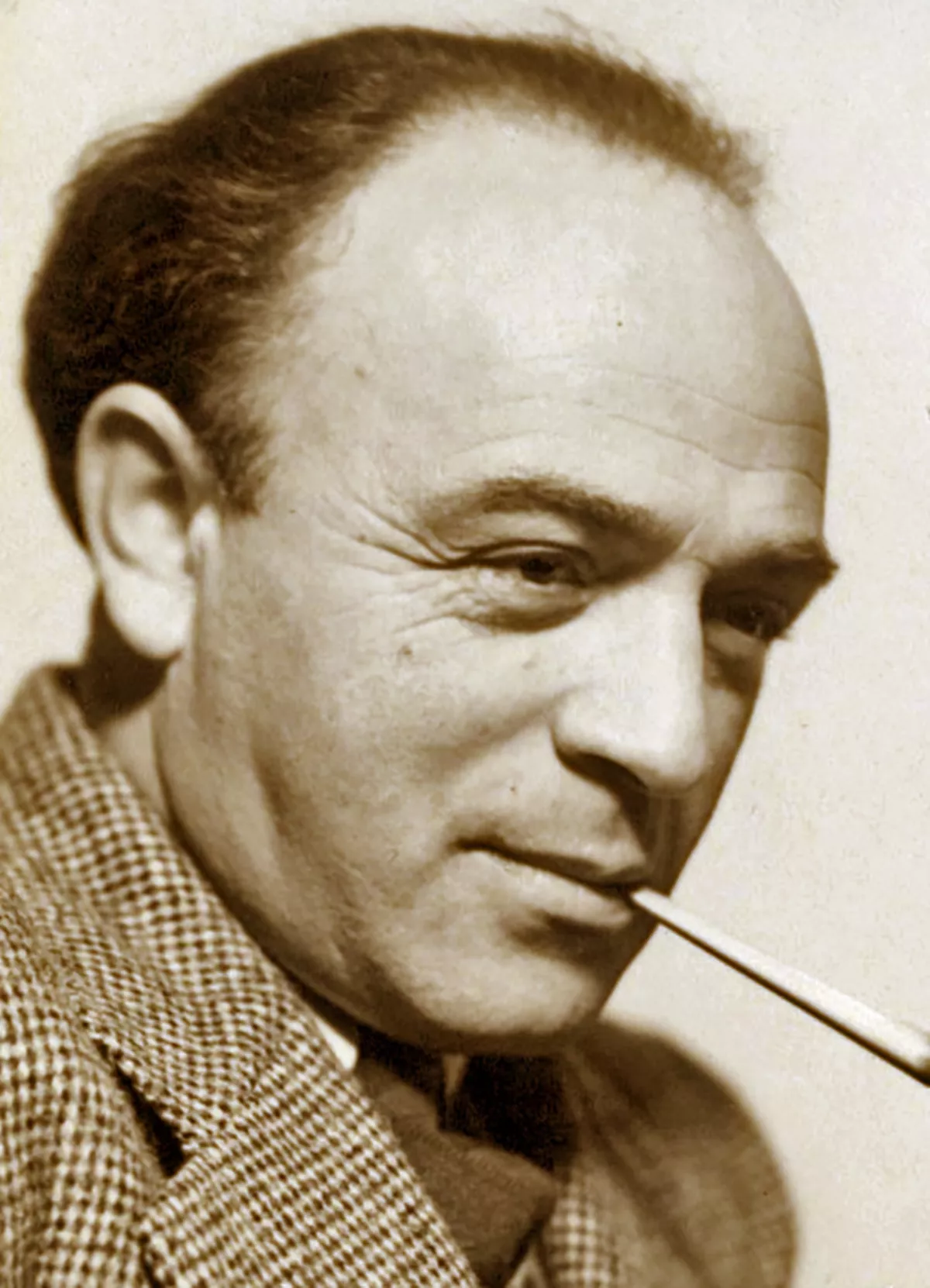

1. Gershon Agron then joined the Zionist Commission as a press officer and helped expand the Jewish Telegraphic Agency upon his return to the United States, of which he served as editor.

1.

1. Gershon Agron then joined the Zionist Commission as a press officer and helped expand the Jewish Telegraphic Agency upon his return to the United States, of which he served as editor.

Gershon Agron lobbied for the creation of Mandatory Palestine and immigrated there permanently in 1924, heading the Zionist Executive press office.

Gershon Agron continued to serve as press officer, promoting Zionism, in the new government, and became mayor of West Jerusalem in 1955.

Gershon Agron's maternal grandfather was a rabbi, and his parents had hoped he would be one, too.

Gershon Agron received an education as a child based in traditional Eastern European Jewry and Judaism in general, before he immigrated with his family to the United States in 1906.

Gershon Agron grew up in Philadelphia, where he attended Mishkan Israel Talmudic School and Brown Preparatory School, and became friends with Israel Goldstein.

The family later lived in New York, where Gershon Agron worked pushing a handcart in the Garment District.

Gershon Agron attended several universities, all in Philadelphia: Temple University, Gratz College, Dropsie College, and the University of Pennsylvania.

Gershon Agron was a firm Labor Zionist, which influenced his choice to attend Temple University in 1914; by 1917, he was a strong critic of Labor Zionism and was a General Zionist.

In 1915, Gershon Agron began working as a journalist in the United States for Jewish newspapers in English and Yiddish: his first newspaper job was writing obituaries and then editorials for The Jewish World in 1915, for which he gave up his rabbinical training, and he became editor of WZO paper Das Judische Volk in 1917, for which he moved to New York.

In March 1918, Gershon Agron was a registered annual member of the Jewish Publication Society, and was living at 731 Jackson Street in Philadelphia.

Gershon Agron joined the Jewish Legion in April 1918, becoming a corporal and then sergeant during training in Windsor and Plymouth.

Gershon Agron was "hand-picked from the beginning" to be the spokesman of the American Jews, and his progress was of import to Zionist Organization of America officials.

Gershon Agron fought in Ottoman Palestine in World War I, sending dispatches back from the front for the ZOA.

In 1919, Gershon Agron wrote a pamphlet, "Survey of the Jewish Battalions", for the Zionist Commission, in which he "lavishly recollected" an enthusiasm among American Jewry for the Legion once war was declared, highlighting the Zionist ideals of recruits.

Gershon Agron's report was idealised, focusing on success and cultural connections, while avoiding mentions of many interpersonal conflicts and other disappointments among recruits; months after it was published, Agron expressed distaste at his own words, including his kindness to write that the English soldiers' fortune to not be stationed in the Tell El Kebir desert with the Americans was accidental.

Gershon Agron was demobilised locally in 1920; he spent his last months in the military working in the Orderly Room and, upon discovering Legion records would likely be destroyed afterwards, "borrowed these papers for safe keeping".

In New York in 1922, Gershon Agron helped found the American Jewish Legion organisation, serving as its first chairman.

Gershon Agron was one of the first Americans to permanently settle in Palestine.

When he was discharged from the Jewish Legion, Gershon Agron became a member of the Yishuv, living in Jerusalem.

Gershon Agron then relocated to the United States in 1921 to help set up the new global venture of the Jewish Correspondence Bureau, based in New York, becoming its news editor.

In taking over the JTA, Gershon Agron officially left Keren Hayesod, both seeing himself first as a journalist and wanting distance from the bureaucracy of the foundation.

In June 1921, Agron published some correspondence he had with president Warren G Harding, vice president Calvin Coolidge, and British Ambassador Geddes, showing to the public that they all gave some form of support to a Jewish state in Palestine.

Gershon Agron was impatient about immigrating to Palestine, though wrote that he had not wanted to return until he had made significant connections in journalism, choosing to rejoin the yishuv in 1924.

Gershon Agron continued in his public service roles, being the ZOA representative in Jerusalem by September 1929.

Shortly after his Hearst deal, Gershon Agron began writing the Palestine Bulletin for the JTA, which was circulated around the Arab world.

Gershon Agron had been told he could have editorial control over the Bulletin but was not given such freedom; he started considering founding his own newspaper.

Gershon Agron's want for a newspaper with political purpose further developed following the 1929 Palestine riots.

Gershon Agron admitted many of his Zionist biases, saying that under his editorship, The Post deliberately minimised the oppositions of Arabs to Israel and belittled Palestinian Arab views.

Louis Fischer, a fellow Jewish Legion soldier and friend but antagonist of Gershon Agron, was more interested in Russian and Communist ideology; he described Gershon Agron's journalism work as pure Zionist propaganda and "regarded [it] as a poor career choice".

Gershon Agron became a war correspondent, covering the North African campaign from 1941 to 1943; he visited Turkey in 1942 and was there when the MV Struma, carrying Jewish refugees from Europe, sank, which he blamed on the Allies.

In June 1945, following World War II, Hans Morgenthau requested Agron write to US president Harry S Truman to update him on the mood of the Jews in Palestine, particularly in response to the White Paper of 1939.

Gershon Agron affirmed to Morgenthau that should the Allies show support for Zionist resolution in Palestine there would be "no trouble" with the Arabs.

On 1 February 1948, the office building was the target of a truck bombing, which killed three people; Gershon Agron had not been in his office.

On various occasions, Gershon Agron served as envoy of the WZO, and he was a delegate at International Zionist Congresses.

Gershon Agron held special commissions for investigating conditions of Jews in Palestine, Thessaloniki, Aden, India, Iraq, and Romania.

Gershon Agron would visit San Francisco on many occasions, becoming well known in the city and speaking at local organisations.

Gershon Agron had been asked to take the position during the war, in a telegram from Moshe Sharett; though Agron took it out of duty, he had been hoping to be named Israel's ambassador to Britain.

Gershon Agron began working at the Post full-time again on 15 February 1951, allowing Lurie to continue as interim editor while he instead travelled to the UK and US for United Jewish Appeal fundraiding opportunities; though he was successful, he found the travel exhausting, and stopped.

Gershon Agron took the role after a period of government intervention because of chaotic infighting preventing proper city administration.

Under Gershon Agron, there were many fewer fights in the city council, and those which did happen he could reportedly end quickly by reminding the chamber that time cost money.

Gershon Agron remained in office until his death in 1959.

Gershon Agron became a hasbara pioneer after becoming disillusioned with the British control over Palestine.

On his deathbed, in 1959, Gershon Agron assented to an international edition of the Jerusalem Post being created, which the newspaper said was an acknowledgment of "the growing importance of the Diaspora".

Gershon Agron wrote in 1925 that, to build a successful society in Palestine, the Yishuv required many American Jews, though he was careful to warn that these potential immigrants must understand what migration would mean.

When Gershon Agron referred to Jews and Palestinian Jews, he meant only Ashkenazi Jews; he thought that Sephardim were "thoroughly Egyptianized, Arab-ized".

Silver wrote that Gershon Agron initially took a more assistant role in Palestinian Zionism, conflicted that he had been an advocate for Zionism outside of Palestine for longer than he had lived there; Silver described the 1920s as Gershon Agron's "period of existential groping".

Gershon Agron only told his wife after they married that he expected her to emigrate to Palestine with him, which she did reluctantly.

When Gershon Agron's children were young, they attended Debora Kallen's Parents Educational Association School in Jerusalem.

Gershon Agron noted that she struggled to empathise with Holocaust survivors who arrived, saying this was due to an "unjustified arrogance" stemming from Zionist education which saw non-Palestinian Jews as other.

Gershon Agron felt that in school and in society, her generation was subject to Zionist "brainwashing".

Gershon Agron attended William Penn High School and Goucher College, where she was elected as a member of the Phi Beta Kappa honor society in 1917.

Gershon Agron lived in various hotels, finally settling on the Excelsior Hotel in Rome at the same time as figures like Orson Welles spent time there, as it would allow him to keep a dog; he turned his room into a communications headquarters.

Later in the war, Dani Gershon Agron recruited American pilots Jack Weinronk and Danny Rosin.

Gershon Agron had always had poor eyesight and, in 1956, he drove over a landmine from the Suez Crisis and lost a leg.

The family was one of the wealthiest in Jerusalem even when they first settled there, only becoming more comfortable as Gershon Agron became more prominent.

However, he crafted "a bourgeois brand of idealism" to fit in with the ideals of Zionism and the society of the Yishuv, pretending that he owned and lived off little; Silver suggested that Gershon Agron was very self-conscious and anxious about gaining success, and would want to hide this.

Gershon Agron was admitted to the Hadassah Medical Center in early September 1959, for routine liver surgery to treat cancer.

Gershon Agron received a state funeral, attended by over 40,000 people, with a eulogy from Sharett calling him "one of the greatest personalities of the Zionist movement".

Gershon Agron was buried at Har HaMenuchot, near the gravesites of Peretz Smolenskin and Joseph Klausner.

The cornerstone of Gershon Agron House was laid on 10 October 1961 by Sharett; in a tribute at the cornerstone ceremony, Goldstein said Gershon Agron was "the journalist par excellence", praising his services as an ambassador for Israel and Zionism:.

Gershon Agron's warm, sparkling personality captured many hearts and his brilliant, untrammeled approach captured many minds.

Gershon Agron disarmed antagonists, converted neutrals into partisans, and partisans into enthusiasts.

In 2012, Ulf Hannerz said Gershon Agron was "a culture hero of Israeli journalism".

The personal papers of Gershon Agron are kept at the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem.