1.

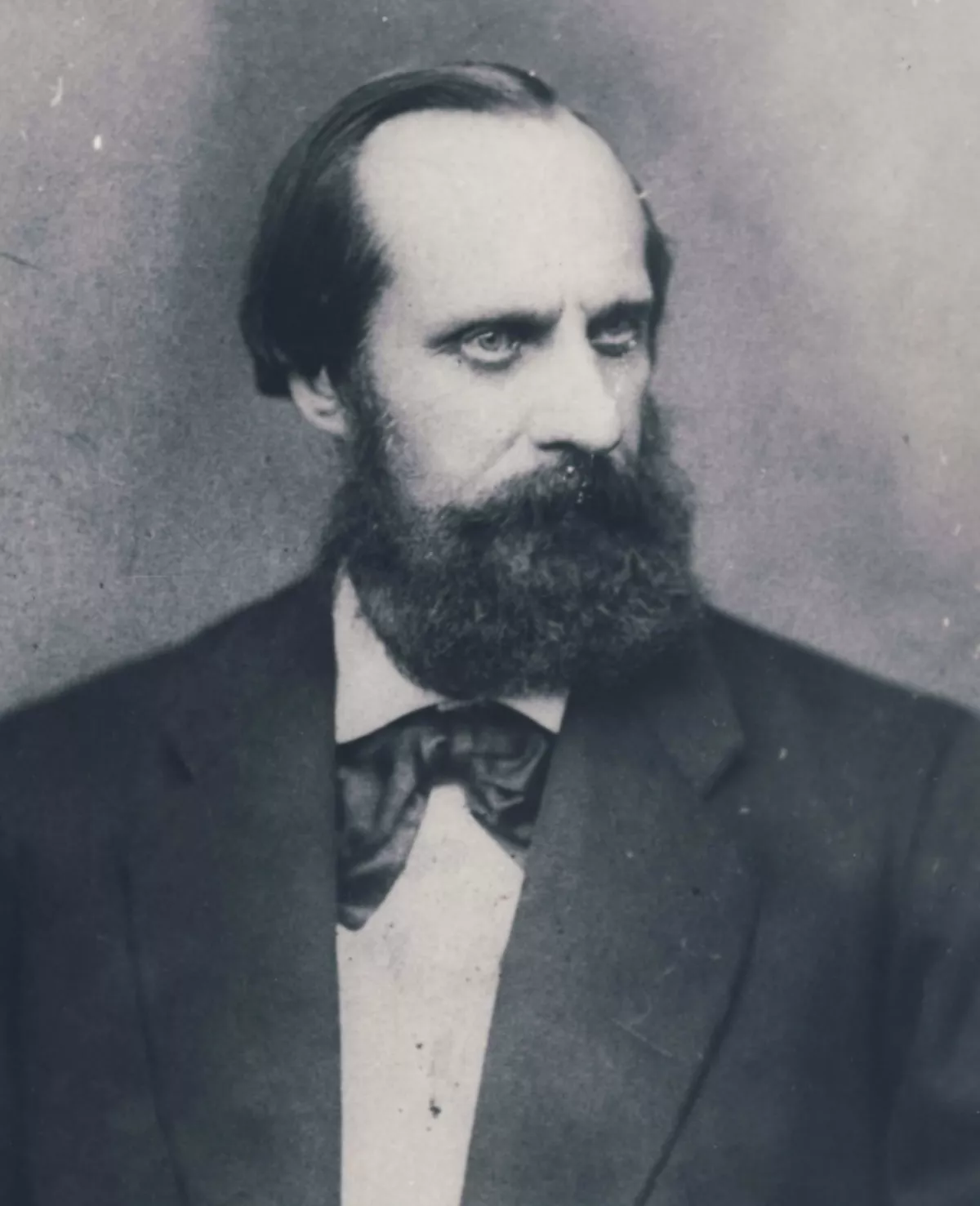

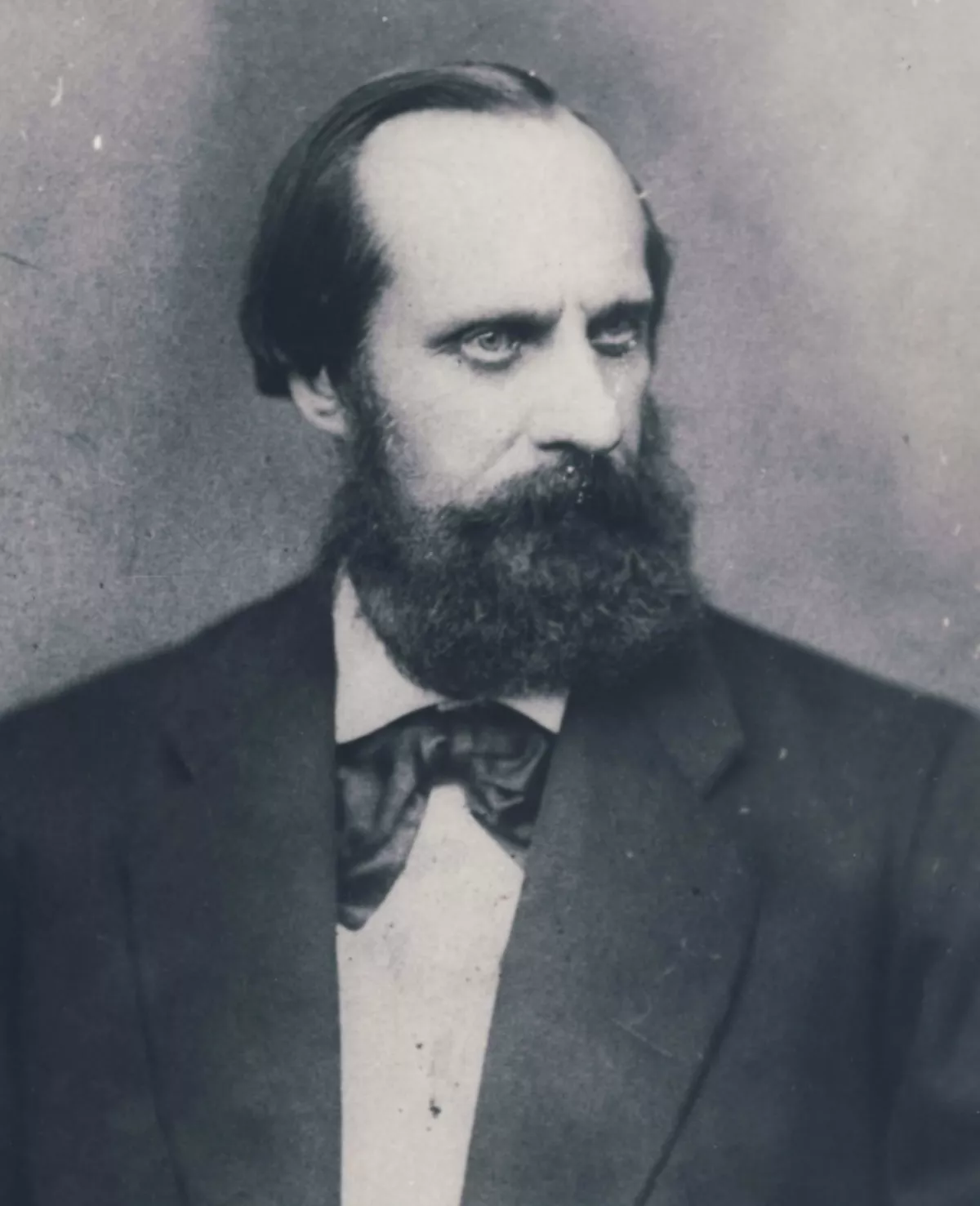

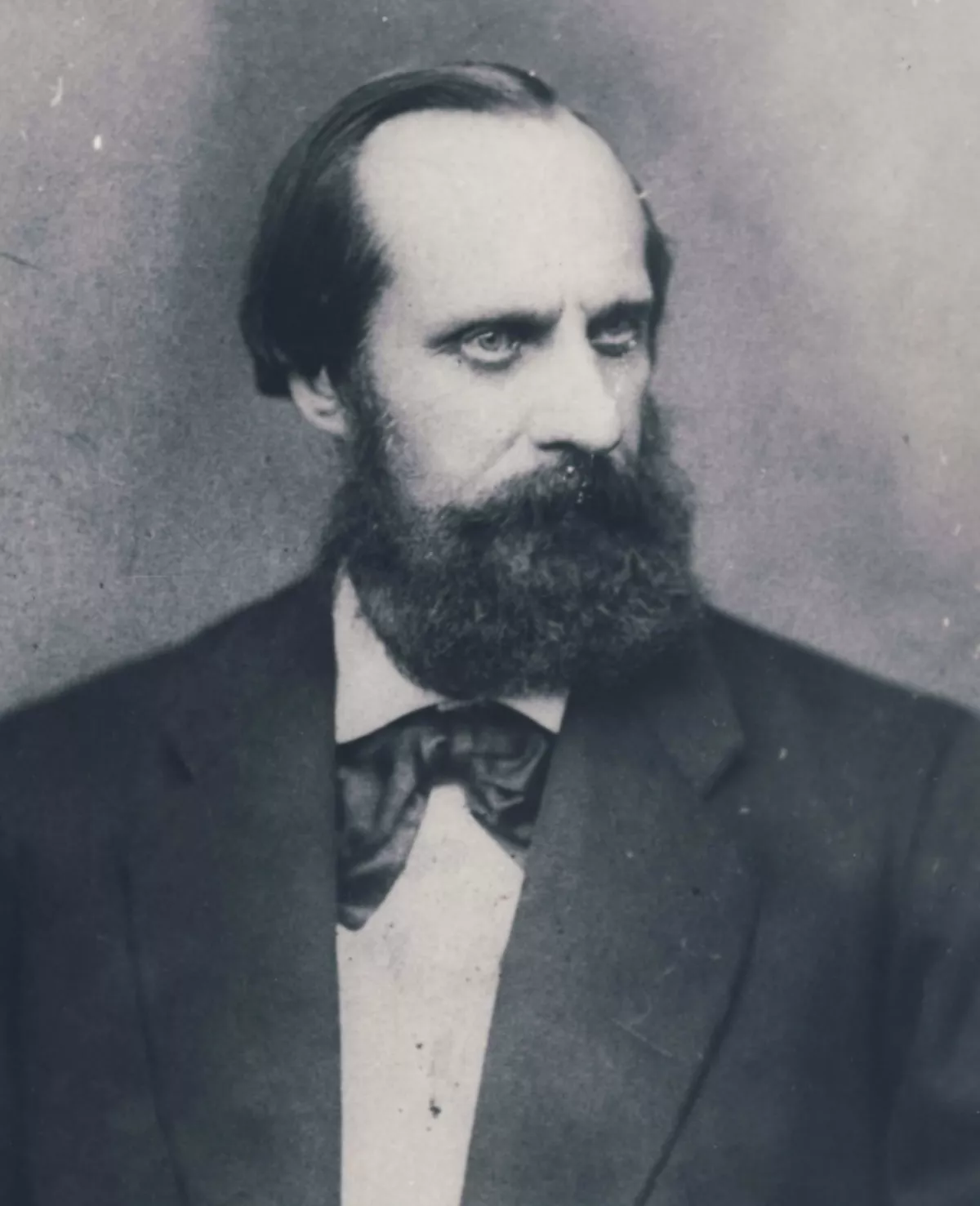

1. Grigore Sturdza was the son of Prince Mihail Sturdza, a scion of ancient boyardom, and, during the 1840s, an heir apparent to the Moldavian throne, for which he was known throughout his later life as Moldavia's Beizadea.

1.

1. Grigore Sturdza was the son of Prince Mihail Sturdza, a scion of ancient boyardom, and, during the 1840s, an heir apparent to the Moldavian throne, for which he was known throughout his later life as Moldavia's Beizadea.

Grigore and Mihail Sturdza competed with each other for the princely election of 1858, with their rivalry playing a major part in the victory of a third candidate, Cuza.

Grigore Sturdza was absorbed and financially exhausted by a long trial involving his family inheritance.

The Beizadeas grandfather, Logothete Grigorascu Grigore Sturdza, enshrined a legend according to which the family was a branch of the Hungarian Thurzos, and that it ultimately had Dalmatian origins.

Reportedly, Grigore Sturdza did not favor this claim, but instead regarded himself as a descendant of Vlad the Impaler.

Grigore Sturdza's parents were Mihail and his first wife, Elisabeta "Saftica" Paladi, who descended from the Rosetti family.

The Grigore Sturdza ascendancy was interrupted by the Russo-Turkish War of 1828, during which Prince Ioan was captured by the Imperial Russian Army.

Grigore Sturdza began service in the Moldavian princely militia in August 1834, when he became a cavalry cadet.

Grigore Sturdza was much impressed by the experience, which shaped his lifelong belief in militarism.

Grigore Sturdza earned top marks for his academic interests, but for his courageous and passionate character; he and Dimitrie graduated together, enlisting at Berlin University in October 1837.

Grigore Sturdza was supposed to take lectures in natural law from Eduard Gans, but the latter died before he could enlist.

Grigore Sturdza eventually studied political economy under Adolph Riedel, and technology with Heinrich Gustav Magnus, renouncing all legal study in April 1840; according to various records, he took history with Leopold von Ranke and was introduced to natural sciences by Alexander von Humboldt and Heinrich Wilhelm Dove.

Biographers speculate that he probably attended a Prussian military school, though it remains more clearly attested that Grigore Sturdza was being privately tutored by an artillery officer of the Gardekorps.

Grigore Sturdza was already unusually tall, a trait that he inherited from his Rosetti mother, and had been born with "outstanding muscular strength".

Writer George Costescu similarly notes that, in maturity, Grigore Sturdza was an avid and tireless swimmer, especially fond of the waters outside Agigea; in winter, he enjoyed wrestling matches with a good friend, George San-Marin.

Grigore Sturdza abandoned his studies in Berlin in February 1843, without getting his diploma.

One version of the story is that young Grigore Sturdza obtained from her a pledge that she would marry him and follow him to Moldavia.

Grigore Sturdza would be well advised to handle his own ministry, which he has been handling very poorly.

Grigore Sturdza continued to defy his father by taking hold of the estate revenues of Perieni and Neamt Monastery.

Duclos provides a different narrative, according to which the Beizadea had simply grown tired of the Countess, and had her sign a "convention" ending the marriage; in both his and G Sion's version, the conflict ends with Grigore asking for the Prince's forgiveness.

Grigore Sturdza began holding land to his own name: at Cristesti, he used, and sometimes lived in, a giant durmast oak with a view of the Ceahlau Massif.

At the time, Grigore Sturdza became interested in projects of sea and river commercial navigation.

Grigore Sturdza then worked with specialized retailers from the Pedemonte House, but failed to honor his obligations, and was taken to court.

The incident became an international scandal after Moldavian courts ruled that Grigore Sturdza was owed reparations and legal fees by Pedemonte.

Grigore Sturdza, it remains an issue of contention among his colleagues whether Grigore Sturdza was ever legally married to Countess Dash.

Grigore Sturdza reflected on her relationship with Sturdza in her 1848 novel, Michael le Moldave.

Dimitrie was nominally in charge, as Hatman, but, as recounted by Radu Rosetti, Grigore Sturdza, being "more energetic and competent", personally supervised the revolutionaries' arrest and mistreatment.

Grigore Sturdza writes that "Gregoire Sturdza, son of the Prince" masterminded the ambush of Colonel Alexandru Ioan Cuza and other regime critics inside Iasi's Casimir House.

Grigore Sturdza is believed to have similarly handled the arrest of another young revolutionary, Manolache Costache Epureanu; Kogalniceanu had joined the revolutionary movement, but escaped into exile.

Grigore Sturdza reportedly maintained an "overt and implacable dislike" for the Beizadea and, before his departure, accused him of having defrauded Neamt Monastery of "no less than forty thousand ducats".

Alecsandri claimed that Grigore Sturdza's Arnauts had ransacked boyar homes, stolen precious clocks owned by Georgios Kantakouzinos, and mistreatead prisoners.

Grigore Sturdza was himself expelled from the country due to a Russian veto, which some, including Stokera, believed was possibly prompted by Grigore's "bad behavior".

Grigore Sturdza had married a distant relative, Catrina Sturdza, with whom he established a family branch in France.

The matter was investigated by Lascar Catargiu, at the time the civil inspector, who found that Grigore Sturdza had indeed disregarded law and custom.

Grigore Sturdza fought with distinction in Wallachia, beginning with the Battle of Oltenita; he was then involved in the engagements at Cetate, displaying "rather insane courage" as a mounted sniper, who took aim at enemy officers while fired upon by the Russian artillery.

Grigore Sturdza viewed the conflict as essential in effecting Italian unification, and proposed that a more visible Romanian engagement could have similarly resulted in Moldo-Wallachian unification.

Grigore Sturdza networked with the pro-Ottoman Wallachian Ion Ghica, but the two split in February 1854.

Grigore Sturdza's letters refer to Pasoalcas birthday, which doubled as a celebration of Romanian nationalism: they "listened with our ears and our souls" to a performance by the Lautari.

Grigore Sturdza was then reassigned to a section of the Danube army, under Halim Pasha.

Russia's envoy Michel Fanton de Verrayon protested against this appointment, since Grigore Sturdza was a Moldavian national, arguing that he could not be impartial on the territorial issue; the Porte stood by Grigore Sturdza.

The Commission president, Charles George Gordon, was much displeased with Grigore Sturdza's arrival, noting that he was being quarrelsome and created additional hurdles in settling the border disputes.

Grigore Sturdza boasted, to an incredulous audience, that he had personally obtained more territory for Moldavia in Bolgrad County.

The Russian side had repeatedly refused to deal with Grigore Sturdza as a commission member, noting that he was a deserter from their ranks.

Grigore Sturdza Jr recruited the Frenchman Jean Alexandre Vaillant, who put out a Sturdzist brochure that was read with interest by the French Foreign Minister, Alexandre Colonna-Walewski.

Unlike Mihail, Grigore Sturdza Jr wanted to take a seat in the Ad hoc Divan during the concurrent legislative election.

Grigore Sturdza was finally validated by the Divan deputies, 32 votes to 20.

Grigore Sturdza argued that Mihail Sturdza was a "separatist", tainted by his association with Vogoride.

The National Party's V A Urechia claimed that young Sturdza being furious of his father's interference, which had prevented him from swinging the "old boyar" vote.

The Russian consul in Moldavia, Sergei Popov, noted that some partisans of "Grigore Sturdza Mukhlis" had already been found in Bucharest, where they worked to undermine the possibility of a double election.

Grigore Sturdza's coded letter to Czajkowski suggests that he wanted to appoint himself Caimacam through bribery, for which he intended to open a credit line with Antoine Alleon's bank.

Rumors of such intrigues resulted in a temporary clampdown on Polish revolutionary cells in Moldavia: 23 Poles were arrested and 11 convicted during a trial which saw Grigore Sturdza appearing as a witness.

Grigore Sturdza himself rejected the rumor in an open letter carried by Steoa Dunarei, but it was largely confirmed by Poles taken into custody.

Cuza scholar Dumitru Ivanescu suggests that Grigore Sturdza was rendered "harmless" by Wierzbicki's arrest; the regime had no interest in finding him guilty, since such a verdict would have created more division.

Grigore Sturdza then served on the Principalities' Central Judicial Commission, based at Focsani, whereby he introduced legislation which contained the first-ever Romanian references to "human rights".

At this stage, Grigore Sturdza veered back into conservatism, instigating a veto against electoral reform.

Grigore Sturdza was noted for refusing to congratulate Cuza on his birthday, as well as for rejecting any suggestion that the Commission owed its mandate to the Domnitor.

Unlike other Moldavian delegates on the commission, Grigore Sturdza fully supported establishing the national capital in Bucharest; as he put it, Iasi was both insufficiently bourgeois and insufficiently Romanian.

Grigore Sturdza then stood in the Romanian Assembly of Deputies, representing the right-wing opposition to Cuza's egalitarian policies.

Grigore Sturdza upheld a rival project provided for common land in rural communities, with family allotments of, at most, 15 square kilometers.

Grigore Sturdza preserved his oppositionist stance following the creation in early 1862 of a unified cabinet, headed by the Prime Minister of Romania.

Grigore Sturdza was persuaded that Cuza was turning to dictatorial means such as changing governments "with each season" and asking civilians to carry out illegal orders.

Grigore Sturdza rejected reunification with the Principalities, on the grounds that Romanian politicians were incompetent and evil.

Grigore Sturdza served for a while as Chief of the Romanian Police section in Iasi, retiring to a position on the board of Sfantul Spiridon Hospital.

The troubled year 1871 signaled Grigore Sturdza's political rise as the leader of an arch-conservative caucus.

Grigore Sturdza however insisted that the Petition be signed by all right-wingers in the Assembly; Junimist deputies, based in Iasi, only agreed to sign parts of the document.

Grigore Sturdza still tried to win over the public with his demands, touring all of Western Moldavia in the summer of 1871.

Rumors rendered by Ionescu suggest that Grigore Sturdza had created himself an appendant body of Freemasonry, and that many inductees quit upon realizing that they were being used.

Grigore Sturdza had by then renounced his claim to the Romanian throne.

Sturdza and his associate Ceaur-Aslan voiced their displeasure when Junimea was co-opted by Catargiu to strengthen "White" chapters in Moldavia; however, Sturdza agreed not to run in the 3rd College at Iasi, leaving it to be contested by the Junimist Petre P Carp, and instead ran for the 4th College at Falciu.

Grigore Sturdza adopted controversial stances during the Romanian War of Independence, which saw Romania aligned with Russia against the Ottomans.

Grigore Sturdza sided with Conservative Generals Gheorghe Manu and Ion Emanuel Florescu.

Grigore Sturdza refused to join the movement, upset that the party leadership went to Epureanu; he was opposed to the mainstream chapters in that he had become a Russophile, wishing for Romania to be brought into the orbit of Tsarist autocracy.

On March 3,1880, Sturdza attempted a show of force, speaking in the Senate against the validation of Alecu D Holban.

From May 1883, Beizadea Grigore Sturdza served in Dimitrie Ghica's commission for constitutional revision.

In January 1882, Grigore Sturdza was being labeled a "Slavophile" by the Austrian press, which reported on his "conventicles" of Iasi in connection with a visit by Miroslav Hubmajer, known for having fought in an anti-Austrian rebellion in 1875.

Grigore Sturdza's speeches drew attention from a Junimist poet-journalist, Mihai Eminescu.

Grigore Sturdza argued that Romania would be better off in an alliance with Russia and the French Republic against the German Empire, insisting that Germany and its Triple Alliance were fundamentally weak.

Grigore Sturdza contended that Romania was helpless in front of a Russian invasion, advising government to declare neutrality and grant safe passage to the Russian armies.

Grigore and Olga Sturdza did not have a happy marriage.

Grigore Sturdza never saw himself bound by matrimonial fidelity, and continued to keep, and brag about, his seraglio that, at any time, comprised twelve concubines; commenting on this "harem", Cantacuzene noted that "customs and decency did not exist for this Sturdza prince".

Grigore Sturdza became fatally ill with pneumonia after bathing in the Siret River.

The family patriarch Mihail Grigore Sturdza died in his Parisian exile on May 7 or 8,1884.

Grigore Sturdza still had his own thoughts on European affairs, and in December 1896 insisted that "Romania should find support in Russia".

Grigore Sturdza recalls his 1894 visit to the Lozonschi villa, which the Beizadea had fitted with massively oversized furniture.

Grigore Sturdza was struck by the former Pasha's "mahogany beard" and 1870s clothes.

Over thirty years, Grigore Sturdza investigated the "fundamental laws of the Universe", producing the eponymous tract Lois fondamentales de l'univers.

One of the tenets of the books was a hypothesis on astrochemistry, with Grigore Sturdza calculating "that there are ninety-three nonillions of trentillions of atoms condensed in the eighty million stars, or altogether one-hundred and eight-six nonillions of trentillions of atoms".

Grigore Sturdza continued to work in designing flying machines with "cardboard wings" which he infamously tested by peasants living on his estates, who suffered broken limbs as a result.

Sturdza's fortune grew to immense proportions after lawyer I C Barozzi, working on his behalf, discovered that Prince Mihail had hidden some 45 million lei in bullion on his various estates; Grigore was owed a third of this wealth.

Grigore Sturdza commissioned a German architect, Julius Reinecke, to construct the Grigore Sturdza Palace of Bucharest.

In January 1895, Sturdza forced his adoptive son, named Grigore, to marry Maria Feodosiev-Cantacuzino.

Grigore Jr's suicide pushed Sturdza to recognize his other sons by various women, including Lieutenant Dimitrie Pavelescu, who became Pavelescu-Sturdza.

Grigore Sturdza was survived by his wife Ralu, who soon began a new life as a nun in Agapia Monastery.

The legal battle over Mihail Grigore Sturdza's inheritance was still ongoing in 1903, by then involving only siblings Dimitrie and Maria.