1.

1. Early in his political career, Hadrian married Vibia Sabina, grandniece of the ruling emperor, Trajan.

1.

1. Early in his political career, Hadrian married Vibia Sabina, grandniece of the ruling emperor, Trajan.

Hadrian earned further disapproval by abandoning Trajan's expansionist policies and territorial gains in Mesopotamia, Assyria, Armenia, and parts of Dacia.

Hadrian preferred to invest in the development of stable, defensible borders and the unification of the empire's disparate peoples as subjects of a panhellenic empire, led by Rome.

Hadrian energetically pursued his own Imperial ideals and personal interests.

Hadrian visited almost every province of the Empire, and indulged a preference for direct intervention in imperial and provincial affairs, especially building projects.

Hadrian is particularly known for building Hadrian's Wall, which marked the northern limit of Britannia.

Hadrian died the same year at Baiae, and Antoninus had him deified, despite opposition from the Senate.

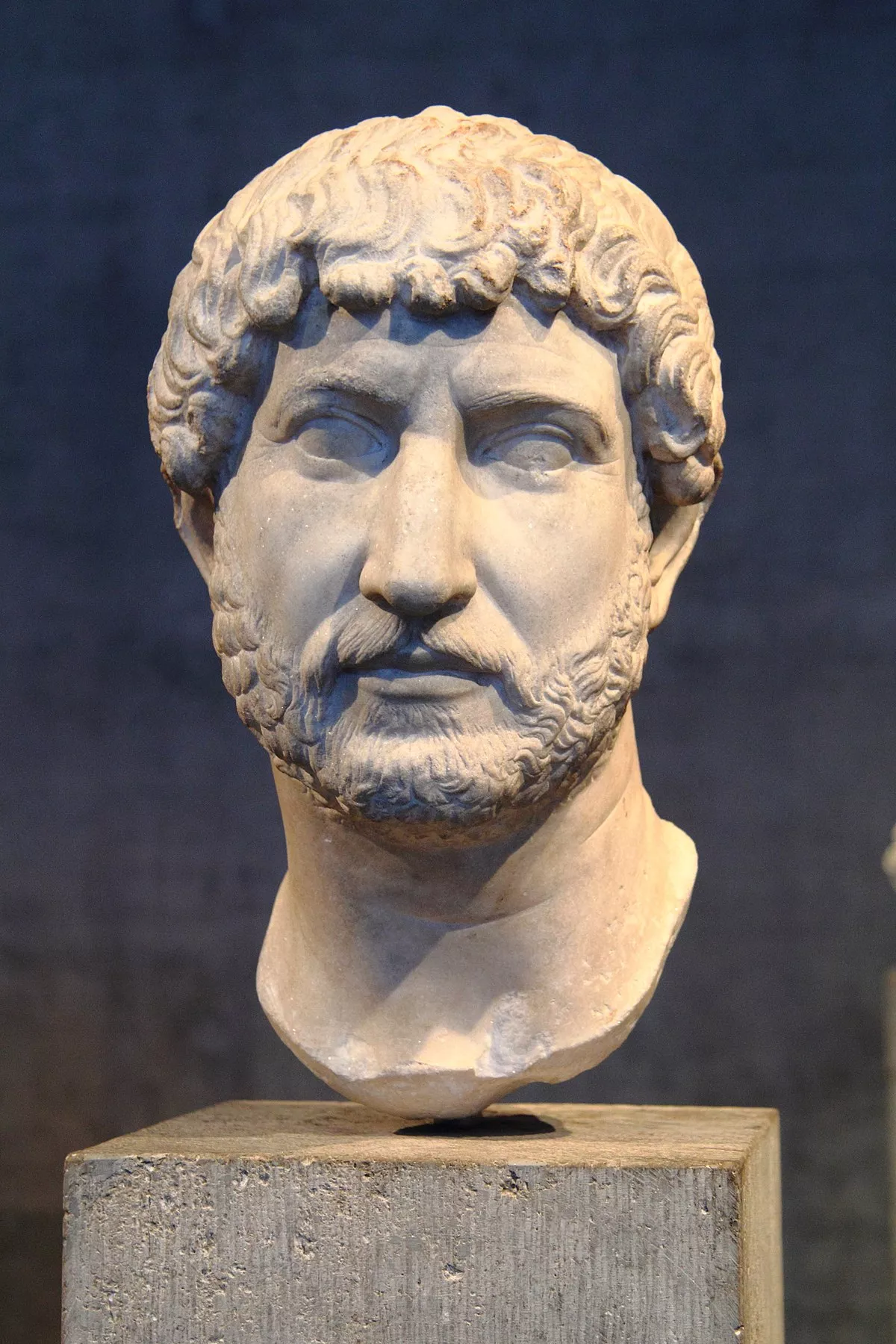

Hadrian has been described as enigmatic and contradictory, with a capacity for both great personal generosity and extreme cruelty and driven by insatiable curiosity, conceit, and ambition.

One Roman biographer claims instead that Hadrian was born in Rome, but this view is held by a minority of scholars.

Hadrian's mother was Domitia Paulina, daughter of a distinguished Roman senatorial family based in Gades.

Hadrian's only sibling was an elder sister, Aelia Domitia Paulina.

Hadrian was later freed by him and ultimately outlived him, as shown by her funerary inscription, which was found at Hadrian's Villa at Tivoli.

Hadrian's parents died in 86 when he was ten years old.

Hadrian then served as a military tribune, first with the LegioII Adiutrix in 95, then with the Legio V Macedonica.

When Nerva died in 98, Hadrian is said to have hastened to Trajan, to inform him ahead of the official envoy sent by the governor, Hadrian's brother-in-law and rival Lucius Julius Ursus Servianus.

Hadrian was released to serve as legate of Legio I Minervia, then as governor of Lower Pannonia in 107, tasked with "holding back the Sarmatians".

Between 107 and 108, Hadrian defeated an invasion of Roman-controlled Banat and Oltenia by the Iazyges.

Now in his mid-thirties, Hadrian travelled to Greece; he was granted Athenian citizenship and was appointed eponymous archon of Athens for a brief time.

Around the time of his quaestorship, in 100 or 101, Hadrian had married Trajan's seventeen- or eighteen-year-old grandniece, Vibia Sabina.

Hadrian could count on the support of his mother-in-law, Salonia Matidia, who was the daughter of Trajan's beloved sister Ulpia Marciana.

Hadrian seems to have sought influence over Trajan, or Trajan's decisions, through cultivation of the latter's boy favourites; this gave rise to some unexplained quarrel, around the time of Hadrian's marriage to Sabina.

Late in Trajan's reign, Hadrian failed to achieve a senior consulship, being only suffect consul for 108; this gave him parity of status with other members of the senatorial nobility, but no particular distinction befitting an heir designate.

That Hadrian was still in Syria was a further irregularity, as Roman adoption law required the presence of both parties at the adoption ceremony.

An aureus minted early in Hadrian's reign represents the official position; it presents Hadrian as Trajan's "Caesar".

Various public ceremonies were organised on Hadrian's behalf, celebrating his "divine election" by all the gods, whose community now included Trajan, deified at Hadrian's request.

Hadrian remained in the east for a while, suppressing the Jewish revolt that had broken out under Trajan.

Hadrian relieved Judea's governor, the outstanding Moorish general Lusius Quietus, of his personal guard of Moorish auxiliaries; then he moved on to quell disturbances along the Danube frontier.

Hadrian claimed that Attianus had acted on his own initiative, and rewarded him with senatorial status and consular rank; then pensioned him off, no later than 120.

Hadrian assured the senate that henceforth their ancient right to prosecute and judge their own would be respected.

Hadrian was to spend more than half his reign outside Italy.

Whereas previous emperors had, for the most part, relied on the reports of their imperial representatives around the Empire, Hadrian wished to see things for himself.

Hadrian sought to include provincials in a commonwealth of civilised peoples and a common Hellenic culture under Roman supervision.

Hadrian supported the creation of provincial towns, semi-autonomous urban communities with their own customs and laws, rather than the imposition of new Roman colonies with Roman constitutions.

Aelius Aristides would later write that Hadrian "extended over his subjects a protecting hand, raising them as one helps fallen men on their feet".

In 122 Hadrian initiated the construction of a wall "to separate Romans from barbarians".

Hadrian never saw the finished wall that bears his name.

At around this time, Hadrian dismissed his secretary ab epistulis, the biographer Suetonius, for "excessive familiarity" towards the empress.

In 123, Hadrian crossed the Mediterranean to Mauretania, where he personally led a minor campaign against local rebels.

The visit was cut short by reports of war preparations by Parthia; Hadrian quickly headed eastwards.

When Hadrian arrived on the Euphrates, he personally negotiated a settlement with the Parthian King Osroes I, inspected the Roman defences, then set off westwards, along the Black Sea coast.

Hadrian probably wintered in Nicomedia, the main city of Bithynia.

Nicomedia had been hit by an earthquake only shortly before his stay; Hadrian provided funds for its rebuilding and was acclaimed as restorer of the province.

Hadrian arrived in Greece during the autumn of 124 and participated in the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Hadrian refused to intervene in a local dispute between producers of olive oil and the Athenian Assembly and Council, who had imposed production quotas on oil producers; yet he granted an imperial subsidy for the Athenian grain supply.

Hadrian created two foundations to fund Athens' public games, festivals and competitions if no citizen proved wealthy or willing enough to sponsor them as a Gymnasiarch or Agonothetes.

Hadrian restored Mantinea's Temple of Poseidon Hippios, and according to Pausanias, restored the city's original, classical name.

Hadrian rebuilt the ancient shrines of Abae and Megara, and the Heraion of Argos.

The Temple of Olympian Zeus had been under construction for more than five centuries; Hadrian committed the vast resources at his command to ensure that the job would be finished.

On his return to Italy, Hadrian made a detour to Sicily.

Hadrian restored the shrine of Cupra in Cupra Maritima and improved the drainage of the Fucine lake.

Hadrian fell ill around this time; whatever the nature of his illness, it did not stop him from setting off in the spring of 128 to visit Africa.

Hadrian's arrival coincided with the good omen of rain, which ended a drought.

Hadrian returned to Italy in the summer of 128, but his stay was brief, as he set off on another tour that would last three years.

Hadrian had played with the idea of focusing his Greek revival around the Amphictyonic League based in Delphi, but by now he had decided on something far grander.

From Greece, Hadrian proceeded by way of Asia to Egypt, probably conveyed across the Aegean with his entourage by an Ephesian merchant, Lucius Erastus.

Hadrian later sent a letter to the Council of Ephesus, supporting Erastus as a worthy candidate for town councillor and offering to pay the requisite fee.

Hadrian opened his stay in Egypt by restoring Pompey the Great's tomb at Pelusium, offering sacrifice to him as a hero and composing an epigraph for the tomb.

Hadrian bestowed honours on various Palmyrene magnates, among them one Soados, who had done much to protect Palmyrene trade between the Roman Empire and Parthia.

Hadrian renamed Jerusalem Aelia Capitolina after himself and Jupiter Capitolinus and had the city rebuilt in Greek style.

Hadrian is said to have placed the city's main Forum at the junction of the main Cardo and Decumanus Maximus, now the location for the Muristan.

Inscriptions make it clear that in 133, Hadrian took to the field with his armies against the rebels.

Commemorations and achievement awards were kept to a minimum, as Hadrian came to see the war "as a cruel and sudden disappointment to his aspirations" towards a cosmopolitan empire.

Empress Sabina died, probably in 136, after an unhappy marriage with which Hadrian had coped as a political necessity.

That gave credence, after Sabina's death, to the common belief that Hadrian had her poisoned.

Hadrian was the son-in-law of Gaius Avidius Nigrinus, one of the "four consulars" executed in 118.

Hadrian's health was delicate, and his reputation apparently more that "of a voluptuous, well-educated great lord than that of a leader".

Hadrian next adopted Titus Aurelius Fulvus Boionius Arrius Antoninus, who had served Hadrian as one of the five imperial legates of Italy, and as proconsul of Asia.

Hadrian was buried at Puteoli, near Baiae, on an estate that had once belonged to Cicero.

Hadrian's ashes were placed there together with those of his wife Vibia Sabina and his first adopted son, Lucius Aelius Caesar, who died in 138.

Hadrian was given a temple on the Campus Martius, ornamented with reliefs representing the provinces.

Hadrian focused on protection from external and internal threats; on "raising" existing provinces rather than the aggressive acquisition of wealth and territory through subjugation of "foreign" peoples that had characterised the early empire.

Hadrian granted parts of Dacia to the Roxolani Sarmatians; their king, Rasparaganus, received Roman citizenship, client king status, and possibly an increased subsidy.

Hadrian retained control over Osroene through the client king Parthamaspates, who had once served as Trajan's client king of Parthia; and around 123, Hadrian negotiated a peace treaty with the now-independent Parthia.

Arrian kept Hadrian well-informed on matters related to the Black Sea and the Caucasus.

Hadrian is credited with introducing units of heavy cavalry into the Roman army.

Fronto later blamed Hadrian for declining standards in the Roman army of his own time.

Hadrian enacted, through the jurist Salvius Julianus, the first attempt to codify Roman law.

Hadrian codified the customary legal privileges of the wealthiest, most influential, highest-status citizens, who held a traditional right to pay fines when found guilty of relatively minor, non-treasonous offences.

When confronted by a crowd demanding the freeing of a popular slave charioteer, Hadrian replied that he could not free a slave belonging to another person.

Hadrian abolished ergastula, private prisons for slaves in which kidnapped free men had sometimes been illegally detained.

Hadrian issued a general rescript, imposing a ban on castration, performed on freedman or slave, voluntarily or not, on pain of death for both the performer and the patient.

Hadrian enforced dress-standards among the honestiores; senators and knights were expected to wear the toga when in public.

Hadrian had recently died in Rome and had been deified at Hadrian's request.

Hadrian promoted Sagalassos in Greek Pisidia as the Empire's leading imperial cult centre; his exclusively Greek Panhellenion extolled Athens as the spiritual centre of Greek culture.

Hadrian added several imperial cult centres to the existing roster, particularly in Greece, where traditional intercity rivalries were commonplace.

Hadrian was given personal cult as a deity, monuments and civic homage, according to the religious syncretism of the time.

In 136, just two years before his death, Hadrian dedicated his Temple of Venus and Roma.

Hadrian had Antinous deified as Osiris-Antinous by an Egyptian priest at the ancient Temple of Ramesses II, very near the place of his death.

Hadrian dedicated a new temple-city complex there, built in a Graeco-Roman style, and named it Antinoopolis.

Hadrian thus identified an existing native cult with Roman rule.

Hadrian was criticised for the open intensity of his grief at Antinous's death, particularly as he had delayed the apotheosis of his own sister Paulina after her death.

Hadrian continued Trajan's policy on Christians; they should not be sought out and should only be prosecuted for specific offences, such as refusal to swear oaths.

Hadrian had an abiding and enthusiastic interest in art, architecture and public works.

Hadrian was familiar with the rival philosophers Epictetus and Favorinus, and with their works, and held an interest in Roman philosophy.

Shortly before the death of Plotina, Hadrian had granted her wish that the leadership of the Epicurean School in Athens be open to a non-Roman candidate.

Hadrian wrote poetry in both Latin and Greek; one of the few surviving examples is a Latin poem he reportedly composed on his deathbed.

Hadrian underscored the autocratic character of his reign by counting his dies imperii from the day of his acclamation by the armies rather than the senate and legislating by frequent use of imperial decrees to bypass the need for the Senate's approval.

That Hadrian spent half of his reign away from Rome in constant travel probably helped to mitigate the worst of this permanently strained relationship.

In Ronald Syme's view, Hadrian "was a Fuhrer, a Duce, a Caudillo".

Political histories of Hadrian's reign come mostly from later sources, some of them written centuries after the reign itself.

The collection as a whole is notorious for its unreliability, but most modern historians consider its account of Hadrian to be relatively free of outright fictions, and probably based on sound historical sources, principally one of a lost series of imperial biographies by the prominent 3rd-century senator Marius Maximus, who covered the reigns of Nerva through to Elagabalus.

The first modern historian to produce a chronological account of Hadrian's life, supplementing the written sources with other epigraphical, numismatic, and archaeological evidence, was the German 19th-century medievalist Ferdinand Gregorovius.

The French novelist Marguerite Yourcenar wrote a historical novel entitled "Memoirs of Hadrian" first published in French in 1951.