1.

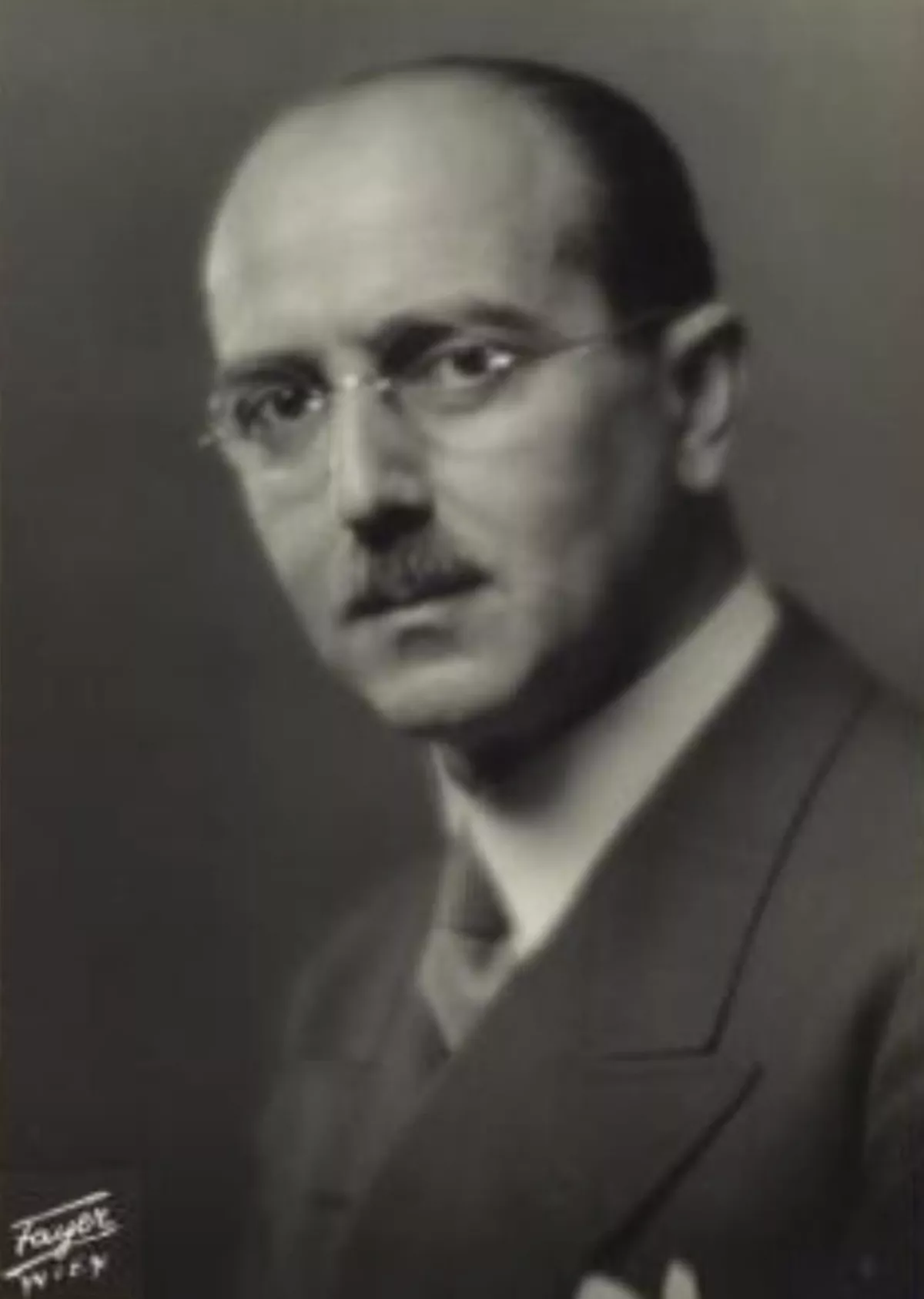

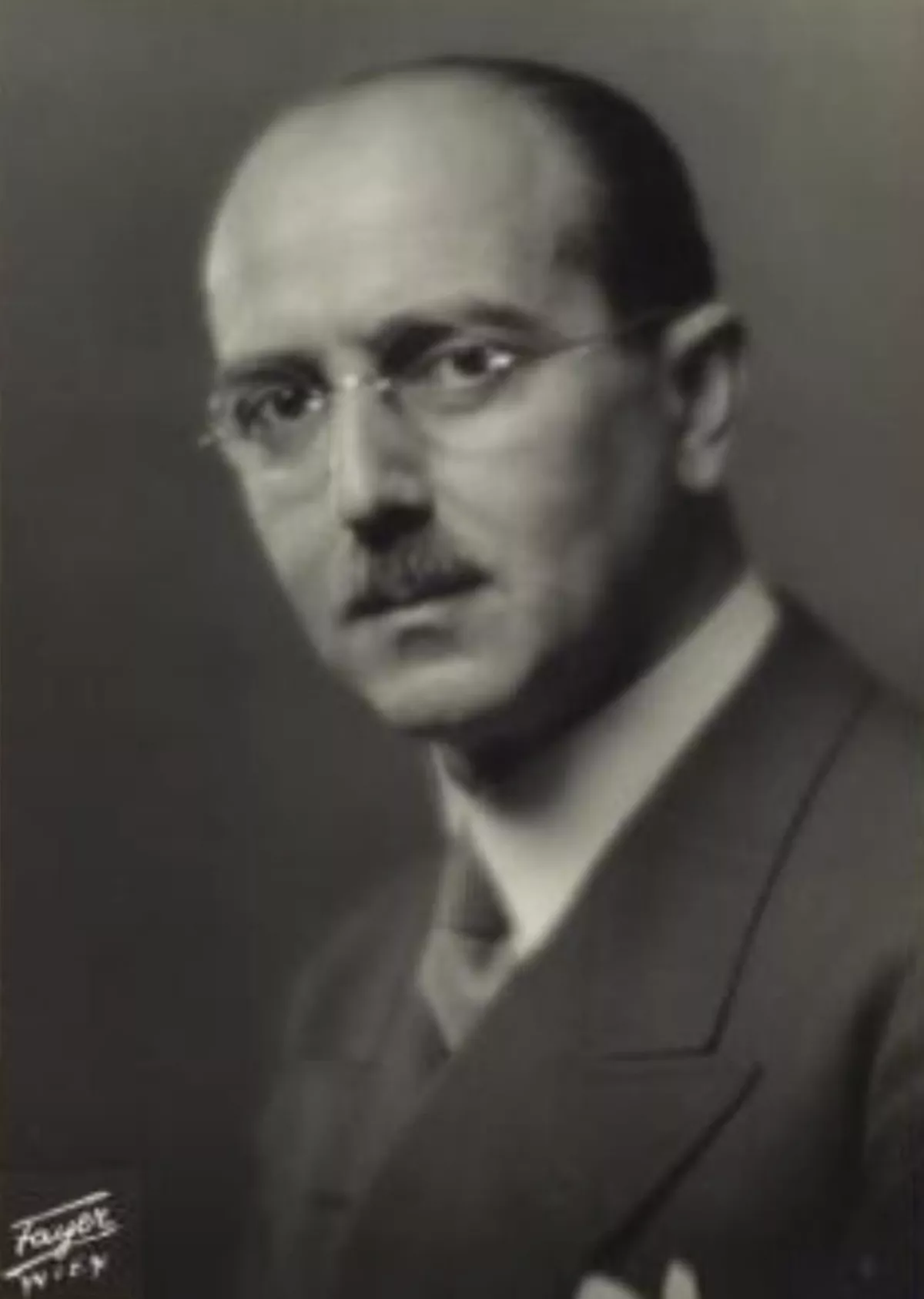

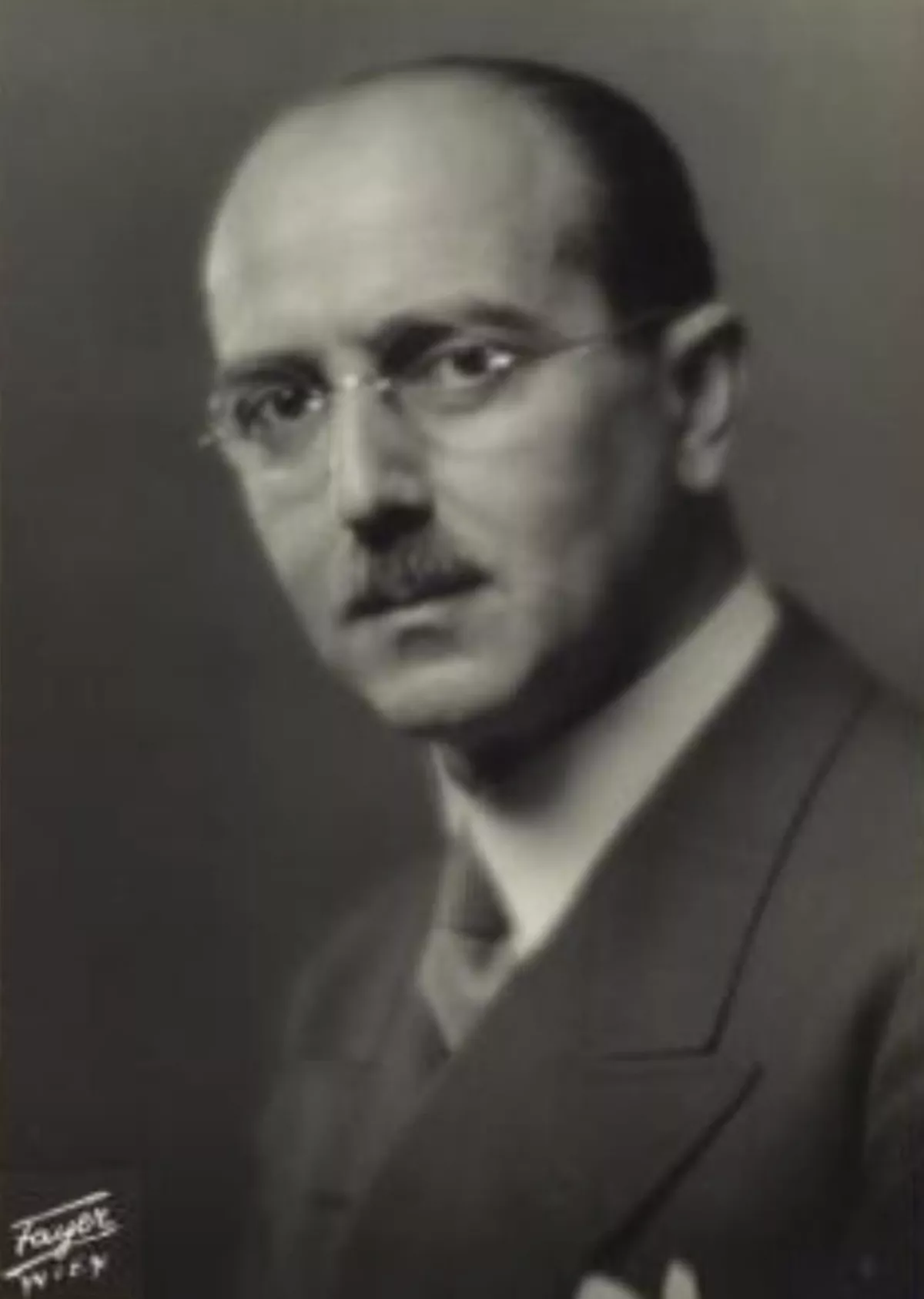

1. Hans Kelsen is known principally for his theory of law, which he named the "pure theory of law ", and for his writings on international law and theory of democracy.

1.

1. Hans Kelsen is known principally for his theory of law, which he named the "pure theory of law ", and for his writings on international law and theory of democracy.

Hans Kelsen was employed in the department of politics at the University of California, Berkeley from 1942 until official retirement in 1952.

Hans Kelsen then rewrote his short book of 1934, titled Reine Rechtslehre, into a much enlarged "second edition" published in 1960; it appeared in an English translation in 1967.

Hans Kelsen was born in Prague into a middle-class, German-speaking, Jewish family.

Hans Kelsen was their first child; there were two younger brothers and a sister.

The family moved to Vienna in 1884, when Hans Kelsen was three years old.

Twice in his life, Hans Kelsen converted to separate religious denominations.

At the time of his dissertation on Dante and Catholicism, Hans Kelsen was baptised as a Roman Catholic on 10 June 1905.

Hans Kelsen obtained the degree of Dr Juris by examination in 1906.

In 1908, studying for his habilitation, Hans Kelsen won a research scholarship which allowed him to attend the University of Heidelberg for three consecutive semesters, where he studied with the distinguished jurist Georg Jellinek before returning to Vienna.

For Hans Kelsen, this was instrumental in the orientation of his own legal thinking in the direction of government strictly according to law, eventually with a heightened emphasis on the importance of a fully elaborated power of judicial review.

At the behest of Chancellor Karl Renner, Hans Kelsen worked on drafting a new Austrian Constitution, enacted in 1920.

Hans Kelsen was appointed to the Constitutional Court, for his lifetime.

Hans Kelsen was supported in his position by Adolf Merkl and Alfred Verdross, while opposition to his view was voiced by Erich Kaufman, Hermann Heller, and Rudolf Smend.

Hans Kelsen was the primary author of its statutes in the state constitution of Austria as he documents in his 1923 book cited above.

Hans Kelsen was inclined to a liberal interpretation of the divorce provision while the administration which had originally appointed him was responding to public pressure for the predominantly Catholic country to take a more conservative position on the issue of the curtailment of divorce.

Hans Kelsen thought that this mission ought to be conferred on the judiciary, especially the Constitutional Court.

Hans Kelsen accepted a professorship at the University of Cologne in 1930.

Hans Kelsen relocated to Geneva, Switzerland where he taught international law at the Graduate Institute of International Studies from 1934 to 1940.

Hans Kelsen was among the strongest critics of Carl Schmitt because Schmitt was advocating for the priority of the political concerns of the state over the adherence by the state to the rule of law.

That Hans Kelsen was the principal defender of Morgenthau's Habilitationschrift is recently documented in the translation of Morgenthau's book titled The Concept of the Political.

When Morgenthau had found a Paris publisher for the volume, he asked Hans Kelsen to re-evaluate it.

Hans Kelsen moved to the United States, giving the prestigious Oliver Wendell Holmes Lectures at Harvard Law School in 1942.

Hans Kelsen was supported by Roscoe Pound for a faculty position at Harvard but opposed by Lon Fuller on the Harvard faculty before becoming a full professor at the department of political science at the University of California, Berkeley in 1945.

Hans Kelsen was defending a position of the distinction of the philosophical definition of justice as it is separable from the application of positive law.

Hans Kelsen, for example, excludes justice from his studies because it is an 'irrational ideal' and therefore 'not subject to cognition.

Shortly after the initiation of the drafting of the UN Charter on 25 April 1945 in San Francisco, Hans Kelsen began the writing of his extended 700-page treatise on the United Nations as a newly appointed professor at the University of California at Berkeley.

In 1955, Hans Kelsen turned to a 100-page essay, "Foundations of Democracy," for the leading philosophy journal Ethics; written during the height of Cold War tensions, it expressed a passionate commitment to the Western model of democracy over soviet and national-socialist forms of government.

Hans Kelsen is considered one of the preeminent jurists of the 20th century and has been highly influential among scholars of jurisprudence and public law, especially in Europe and Latin America although less so in common-law countries.

Hans Kelsen wrote primarily in German, as well as in French and in English.

In drafting the constitutions for both Austria and Czechoslovakia, Hans Kelsen chose to carefully delineate and limit the domain of judicial review to a narrower focus than was originally accommodated by John Marshall.

Hans Kelsen did receive a lifetime appointment to the court of judicial review in Austria and remained on this court for almost an entire decade during the 1920s.

Hans Kelsen explicitly defined positive law to deal with the many ambiguities he associated with the use of natural law in his time, along with the negative influence which it had upon the reception of what was meant even by positive law in contexts apparently removed from the domain of influence normally associated with natural law.

Hans Kelsen wrote book-length studies detailing the many distinctions to be made between the natural sciences and their associated methodology of causal reasoning in contrast to methodology of normative reasoning which he saw as more directly suited to the legal sciences.

Hans Kelsen found that although he had a high respect for Jellinek as a leading scholar of his day, that Jellinek endorsement of a dualist theory of law and state was an impediment to the further development of a legal science which would be supportive of the development of responsible law throughout the twentieth century in addressing the requirements of the new century for the regulation of its society and of its culture.

Hans Kelsen recognized the province of society in an extensive sense which would allow for the discussion of religion, natural law, metaphysics, the arts, etc.

For Hans Kelsen, centralization was a philosophically key position to the understanding of the pure theory of law.

In Hans Kelsen's general assessments, centralization was to often be associated with more modern and highly developed forms of enhancements and improvements to sociological and cultural norms, while the presence of decentralization was a measure of more primitive and less sophisticated observations concerning sociological and cultural norms.

Hans Kelsen devotes one of his longest chapters in the revised version of Pure Theory of Law to discussing the central importance he associated with the dynamic theory of law.

Hans Kelsen adapted and assimilated much of Merkl's approach into his own presentation of the Pure Theory of Law in both its original version and its revised version.

Cohen was a leading neo-Kantian of the time and Hans Kelsen was, in his own way, receptive to many of the ideas which Cohen had expressed in his published book review of Hans Kelsen's writing.

Hans Kelsen had insisted that he had never used this material in the actual writing of his own book, though Cohen's ideas were attractive to him in their own right.

In different contexts, Hans Kelsen would indicate his preferences in different ways, with some neo-Kantians asserting that late in life Hans Kelsen largely abided by the symbolic reading of the term when used in the neo-Kantian context, and as he has documented.

Hans Kelsen, after attending Jellinek's lectures in Heidelberg oriented his interpretation according to the need to extend Jellinek's research past the points which Jellinek had set as its limits.

Hans Kelsen was the principal author of the passages for the incorporation of judicial review in the Constitutions of Austria and Czechoslovakia during the 1910s largely on the model of John Marshall and the American Constitutional experience.

Hans Kelsen became deeply committed to the principle of the adherence of the state to the rule of law above political controversy, while Schmitt adhered to the divergent view of the state deferring to political fiat.

Hans Kelsen believed that the blamelessness associated with Germany's political leaders and military leaders indicated a gross historical inadequacy of international law which could no longer be ignored.

Hans Kelsen devoted much of his writings from the 1930s and leading into the 1940s towards reversing this historical inadequacy which was deeply debated until ultimately Hans Kelsen succeeded in contributing to the international precedent of establishing war crime trials for political leaders and military leaders at the end of WWII at Nuremberg and Tokyo.

Hans Kelsen wrote his 700-page treatise on the United Nations, along with a subsequent two hundred page supplement, which became a standard text book on studying the United Nations for over a decade in the 1950s and 1960s.

Hans Kelsen became a significant contributor to the Cold War debate in publishing books on Bolshevism and communism, which he reasoned were less successful forms of government when compared to democracy.

This, for Hans Kelsen, was especially the case when dealing with the question of the compatibility of different forms of government in relation to the Pure Theory of Law.

Hans Kelsen was a tireless defender of the application legal science in defending his position and was constantly confronting detractors who were unconvinced that the domain of legal science was sufficient to its own subject matter.

Hans Kelsen himself made mixed statements concerning the extensiveness of the greater or lesser strict association of democracy and capitalism.