1.

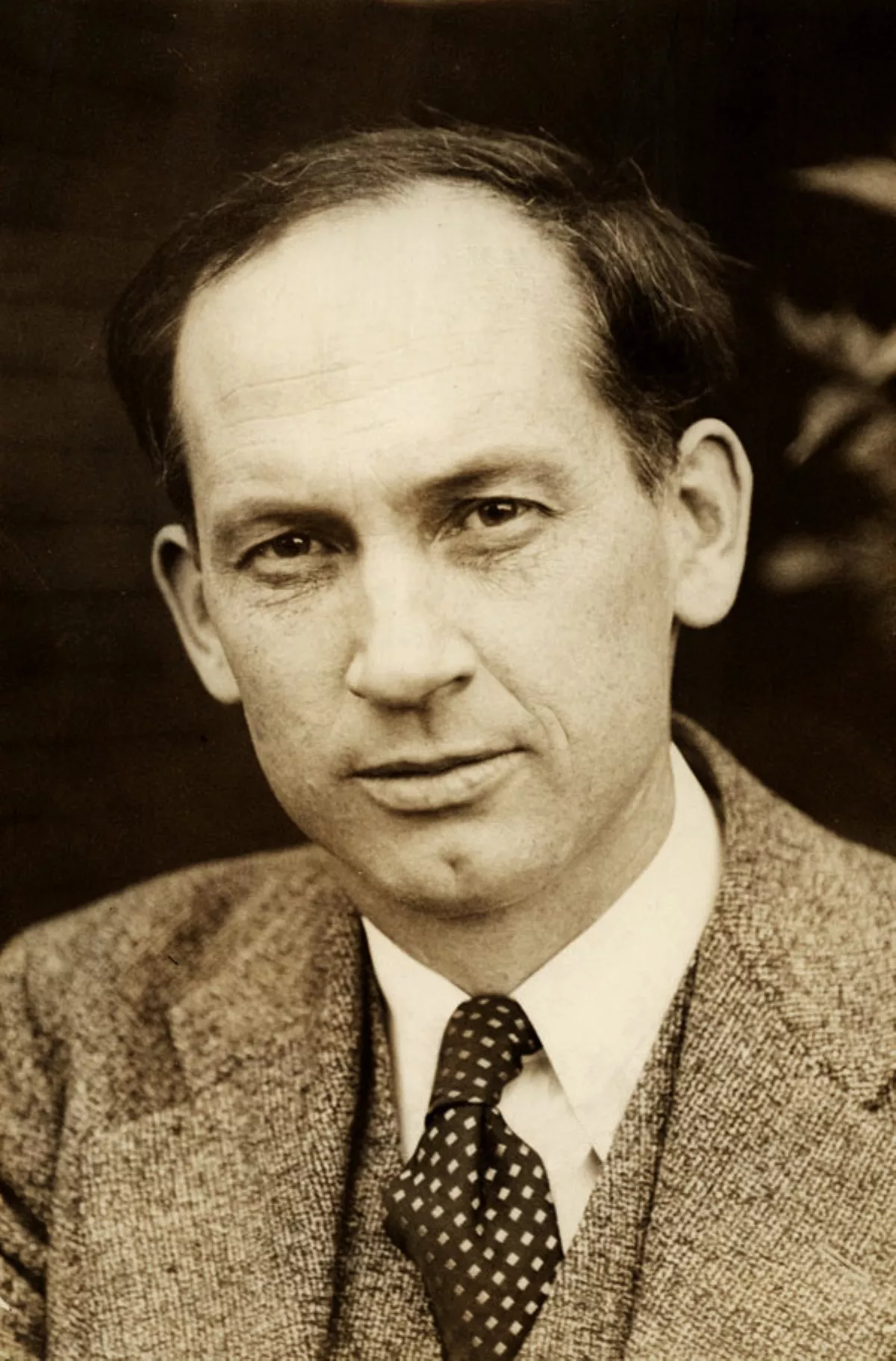

1. Harold Adams Innis was a Canadian professor of political economy at the University of Toronto and the author of seminal works on media, communication theory, and Canadian economic history.

1.

1. Harold Adams Innis was a Canadian professor of political economy at the University of Toronto and the author of seminal works on media, communication theory, and Canadian economic history.

Harold Innis helped develop the staples thesis, which holds that Canada's culture, political history, and economy have been decisively influenced by the exploitation and export of a series of "staples" such as fur, fish, lumber, wheat, mined metals, and coal.

Harold Innis argued, for example, that a balance between oral and written forms of communication contributed to the flourishing of Greek civilization in the 5th century BC.

Harold Innis laid the basis for scholarship that looked at the social sciences from a distinctly Canadian point of view.

Harold Innis was successful in establishing sources of financing for Canadian scholarly research.

Harold Innis warned repeatedly that Canada was becoming a subservient colony to its much more powerful southern neighbor.

Harold Innis tried to defend universities from political and economic pressures.

Harold Innis believed that independent universities, as centres of critical thought, were essential to the survival of Western civilization.

Harold Innis was born on November 5,1894, on a small livestock and dairy farm near the community of Otterville in southwestern Ontario's Oxford County.

Harold Innis became an agnostic in later life, but never lost his interest in religion.

Harold Innis attended the one-room schoolhouse in Otterville and the community's high school.

Harold Innis travelled 20 miles by train to Woodstock, Ontario, to complete his secondary education at a Baptist-run college.

Harold Innis intended to become a public-school teacher and passed the entrance examinations for teacher training, but decided to take a year off to earn the money he would need to support himself at an Ontario teachers' college.

In October 1913, Harold Innis started classes at McMaster University.

Harold Innis learned about Western grievances over high interest rates and steep transportation costs.

Harold Innis was sent to France in the fall of 1916 to fight in the First World War.

On July 7,1917, Harold Innis received a serious shrapnel wound in his right thigh that required eight months of hospital treatment in England.

Harold Innis experienced recurring bouts of depression and nervous exhaustion because of his military service.

Harold Innis completed a Master of Arts degree at McMaster, graduating in April 1918.

Harold Innis did his postgraduate work at the University of Chicago and was awarded his PhD, with a dissertation on the history of Canadian Pacific Railway, in August 1920.

Harold Innis got his first taste of university teaching at Chicago, where he delivered several introductory economics courses.

Mary Quayle Harold Innis was herself a notable economist and writer.

Harold Innis's novel, Stand on a Rainbow appeared in 1943.

Harold Innis edited Harold Innis's posthumous Essays in Canadian Economic History and a 1972 reissue of his Empire and Communications.

Donald Quayle Harold Innis became a geography professor at the State University of New York.

Hugh Harold Innis became a professor at Ryerson University where he taught communications and economics.

Anne Harold Innis Dagg did doctoral work in biology and became an advisor for the independent studies program at the University of Waterloo and published books on zoology, feminism, and Canadian women's history.

Harold Innis wrote his PhD thesis on the history of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Harold Innis maintains that the difficult and expensive construction project was sustained by fears of American annexation of the Canadian West.

Harold Innis is considered the leading founder of a Canadian school of economic thought known as the staples theory.

Harold Innis theorized that the reliance on exporting natural resources made Canada dependent on more industrially advanced countries and resulted in periodic disruptions to economic life as the international demand for staples rose and fell; as the staple itself became increasingly scarce; and, as technological change resulted in shifts from one staple to others.

Harold Innis pointed out, for example, that as furs became scarce and trade in that staple declined, it became necessary to develop and export other staples such as wheat, potash and especially lumber.

In 1920, Harold Innis joined the department of political economy at the University of Toronto.

Harold Innis was assigned to teach courses in commerce, economic history and economic theory.

Harold Innis decided to focus his scholarly research on Canadian economic history, a hugely neglected subject, and he settled on the fur trade as his first area of study.

Harold Innis realized that he had to search out archival documents to understand the history of the fur trade and travel the country himself gathering masses of firsthand information and accumulating what he called "dirt" experience.

Harold Innis travelled so extensively that by the early 1940s, he had visited every part of Canada except for the Western Arctic and the east side of Hudson Bay.

Everywhere that Harold Innis went, his methods were the same: he interviewed people connected with the production of staple products and listened to their stories.

In line with that observation, Harold Innis notably proposes that European settlement of the Saint Lawrence River Valley followed the economic and social patterns of indigenous peoples, making for a Canadian historical and cultural continuity that predates and postdates European settlement.

Unlike many historians who see Canadian history as beginning with the arrival of Europeans, Harold Innis emphasizes the cultural and economic contributions of First Nations peoples.

Harold Innis describes the central role First Nations peoples played in the development of the fur trade.

Harold Innis examined the rise and fall of ancient empires as a way of tracing the effects of communications media.

Harold Innis looked at media that led to the growth of an empire; those that sustained it during its periods of success, and then, the communications changes that hastened an empire's collapse.

Harold Innis tried to show that media 'biases' toward time or space affected the complex interrelationships needed to sustain an empire.

Harold Innis argued that a balance between the spoken word and writing contributed to the flourishing of Ancient Greece in the time of Plato.

The balance between the time-biased medium of speech and the space-biased medium of writing was eventually upset, Harold Innis argued, as the oral tradition gave way to the dominance of writing.

The balance required for cultural survival had been upset by what Harold Innis saw as "mechanized" communications media used to transmit information quickly over long distances.

Western civilization could be saved, Harold Innis argued, only by recovering the balance between space and time.

The next year, in an essay entitled, The Canadian Economy and the Depression, Harold Innis outlined the plight of "a country susceptible to the slightest ground-swell of international disturbance" but beset by regional differences that made it difficult to devise effective solutions.

Harold Innis described a prairie economy dependent on the export of wheat but afflicted by severe drought, on the one hand, and the increased political power of Canada's growing cities, sheltered from direct reliance on the staples trade, on the other.

Harold Innis was appointed president of the Canadian Political Science Association in 1938.

Harold Innis was a central participant in an international project that produced 25 scholarly volumes between 1936 and 1945.

Harold Innis edited and wrote prefaces for the volumes contributed by Canadian scholars.

Frank Underhill, one of Harold Innis's colleagues at the University of Toronto was a founding member of the CCF.

Harold Innis maintained that scholars had no place in active politics and that they should instead devote themselves, first to research on public problems, and then to the production of knowledge based on critical thought.

Harold Innis saw the university, with its emphasis on dialogue, open-mindedness and skepticism, as an institution that could foster such thinking and research.

Eric Havelock, a left-leaning colleague explained many years later that Harold Innis distrusted political "solutions" imported from elsewhere, especially those based on Marxist analysis with its emphasis on class conflict.

Harold Innis played a central role in founding two important sources for the funding of academic research: the Canadian Social Science Research Council and the Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Harold Innis received the Royal Society of Canada's J B Tyrrell Historical Medal in 1944.

In 1945, Harold Innis spent nearly a month in the Soviet Union where he had been invited to attend the 220th anniversary celebrations marking the founding of the country's Academy of Sciences.

Harold Innis saw the Soviet Union as a stabilizing counterbalance to the American emphasis on commercialism, the individual and constant change.

For Harold Innis, Russia was a society within the Western tradition, not an alien civilization.

Harold Innis abhorred the nuclear arms race and saw it as the triumph of force over knowledge, a modern form of the medieval Inquisition.

In 1946, Harold Innis was elected president of the Royal Society of Canada, the country's senior body of scientists and scholars.

In 1947, Harold Innis was appointed the University of Toronto's dean of graduate studies.

Harold Innis was elected an International Member of the American Philosophical Society that same year.

Harold Innis gave the prestigious Beit lectures at Oxford, later published in his book Empire and Communications.

In 1949, Harold Innis was appointed as a commissioner on the federal government's Royal Commission on Transportation, a position that involved extensive travel at a time when his health was starting to fail.

Harold Innis was academically isolated because his colleagues in economics could not fathom how the new work related to his pioneering research in staples theory.

Harold Innis died of prostate cancer on November 8,1952, a few days after his 58th birthday.

Whereas Harold Innis sees communication technology principally affecting social organization and culture, McLuhan sees its principal effect on sensory organization and thought.

McLuhan has much to say about perception and thought but little to say about institutions; Harold Innis says much about institutions and little about perception and thought.

Biographer John Watson notes that Harold Innis's work was profoundly political while McLuhan's was not.

For Watson, Harold Innis's work is therefore more flexible and less deterministic than McLuhan's.