1.

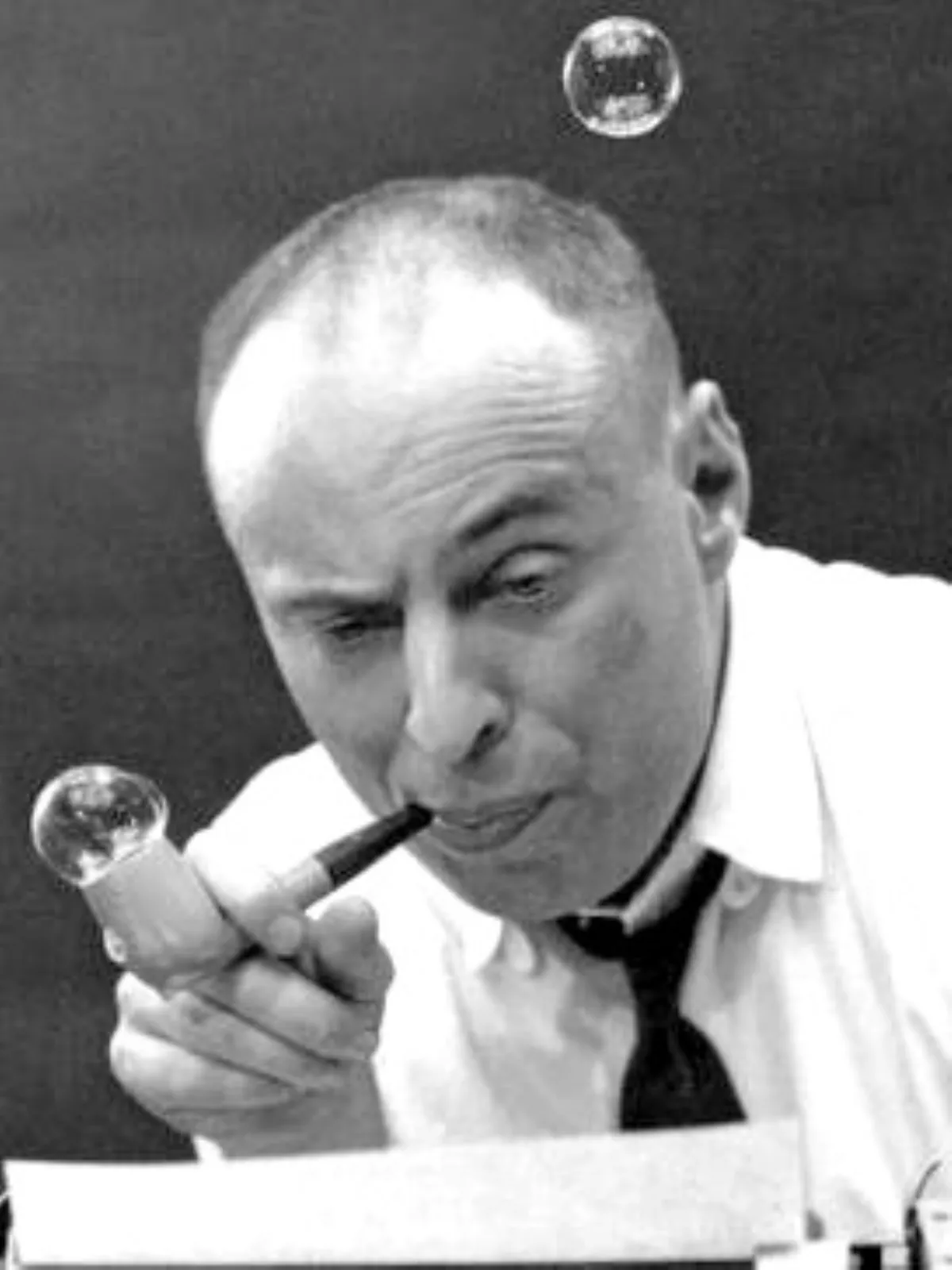

1. Harvey Kurtzman was an American cartoonist and editor.

1.

1. Harvey Kurtzman was an American cartoonist and editor.

Harvey Kurtzman's work is noted for its satire and parody of popular culture, social critique, and attention to detail.

Harvey Kurtzman began to work on the New Trend line of comic books at EC Comics in 1950.

Harvey Kurtzman wrote and edited the Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat war comic books, where he drew many of the carefully researched stories, before he created his most-remembered comic book, Mad, in 1952.

Harvey Kurtzman scripted the stories and had them drawn by top EC cartoonists, most frequently Will Elder, Wally Wood, and Jack Davis; the early Mad was noted for its social critique and parodies of pop culture.

The comic book switched to a magazine format in 1955, and Harvey Kurtzman left it in 1956 over a dispute with EC's owner William Gaines over financial control.

From 1973, Harvey Kurtzman taught cartooning at the School of Visual Arts in New York.

Harvey Kurtzman's work gained greater recognition toward the end of his life, and he oversaw deluxe reprintings of much of his work.

The Harvey Award was named in Kurtzman's honor in 1988.

Harvey Kurtzman was inducted into the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame in 1989, and his work earned five positions on The Comics Journals Top 100 Comics of the 20th Century.

Harvey Kurtzman spoke little of his parents in interviews, and not much is known of their pre-American lives.

The Harvey Kurtzman boys kept their surname, while their mother took that of Perkes.

Harvey Kurtzman was a trade unionist, and the couple read the communist newspaper Daily Worker.

Harvey Kurtzman displayed artistic talent early and his sidewalk chalk drawings drew the attention of children and adults, who gathered around to watch him draw.

Harvey Kurtzman called these strips "Ikey and Mikey", inspired by Goldberg's comic strip Mike and Ike.

Harvey Kurtzman's stepfather had an interest in art and took the boys to museums.

Harvey Kurtzman's mother encouraged his artistic development and enrolled him in art lessons; on Saturdays, he took the subway to Manhattan for formal art instruction.

Harvey Kurtzman's parents had him attend the left-leaning Jewish Camp Kinderland, but he did not enjoy its dogmatic atmosphere.

Harvey Kurtzman fell in love with comic strips and the newly emerging comic books in the late 1930s.

Harvey Kurtzman left after a year to focus on making comic books.

Harvey Kurtzman met Alfred Andriola in 1942, encouraged by a quote in Martin Sheridan's Classic Comics and their Creators where Andriola offered help to aspiring cartoonists.

Harvey Kurtzman continued to do odd jobs in 1942 until he got his first break in the comics industry at Louis Ferstadt's studio, which produced comics for Quality, Ace, Gilberton, and the Daily Worker.

Harvey Kurtzman produced a large amount of undistinguished work in 1942 and 1943, which he later called "very crude, very ugly stuff", before he was drafted in 1943 for service in World War II.

Harvey Kurtzman trained for the infantry, but was never sent overseas.

Harvey Kurtzman was stationed in Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas.

Harvey Kurtzman illustrated instruction manuals, posters, and flyers, and contributed cartoons to camp newspapers, and newsletters.

The quantity of work allowed Harvey Kurtzman to hone his style, which became more refined and distinct.

Harvey Kurtzman applied to the newspaper PM, but his portfolio was rejected by cartoon editor Walt Kelly.

Harvey Kurtzman had been doing crossword puzzles for publisher Martin Goodman since early in his career.

Harvey Kurtzman offered Kurtzman work doing one-page fillers, work that paid little.

At a Music and Art reunion in early 1946 Harvey Kurtzman met Adele Hasan, who was one of the staff members at Timely and was dating Will Elder.

Harvey Kurtzman "stuffed the ballot box" in Kurtzman's favor, which prompted an astonished Stan Lee to assign Kurtzman more work.

Harvey Kurtzman was given the talking animal feature Pigtales at regular freelance rates, as well as miscellaneous other assignments.

In 1948 Harvey Kurtzman produced a Sunday comic strip, Silver Linings, which ran infrequently in the New York Herald Tribune between March and June.

Harvey Kurtzman was assigned artwork duties for the Lee-scripted Rusty, an imitation of Chic Young's comic strip Blondie, but was disappointed with this type of work and began looking for other employment.

Harvey Kurtzman sold episodes of the one-pagers Egghead Doodle and Genius to Timely and Al Capp's Toby Press on a freelance basis.

Harvey Kurtzman sold longer pieces to Toby, including episodes of his Western parody Pot Shot Pete, a short-lived series that hinted at the pop-culture satire Kurtzman was to become known for.

Harvey Kurtzman did a number of children's books, four of which were collaborations with Rene Goscinny.

That spring, EC's "New Trend" line of horror, fantasy, and science fiction comics began, and Harvey Kurtzman contributed stories in these genres.

Harvey Kurtzman rejected the idealization of war that had swept the US since World War II.

Harvey Kurtzman spent hours in the New York Public Library in search of the detailed truth behind the stories he was writing, sometimes taking days or weeks to research a story.

Harvey Kurtzman's research included interviewing and corresponding with GIs taking a ride aboard a rescue plane, and sending his assistant Jerry DeFuccio for a ride in a submarine to gather sound effects.

Harvey Kurtzman sought to tell what he saw as the objective truth about war, deglamorizing it and showing its futility, though the stories were not explicitly anti-war.

Harvey Kurtzman was given a great deal of artistic freedom by Gaines, but was himself a strict taskmaster.

Harvey Kurtzman insisted that the artists who drew his stories not deviate from his layouts.

Harvey Kurtzman's laborious working methods meant he was less prolific than fellow EC writer and editor Al Feldstein, and Harvey Kurtzman felt financially underappreciated for the amount of effort he poured into his work.

Harvey Kurtzman was financially burdened with a mortgage and a family.

Harvey Kurtzman detested the horror content of the books Feldstein was producing, and which consistently outsold his own work.

Harvey Kurtzman believed these stories had the same sort of influence on children that the chauvinism of war comics which he believed he worked hard against in his own work.

Mad debuted in August 1952, and Harvey Kurtzman scripted every story in the first twenty-three issues.

The stories in Mad targeted what Harvey Kurtzman saw as fundamental untruths in the subjects parodied, inspired by the irreverent humor found in college humor magazines.

Harvey Kurtzman poured himself into Mad, putting as much effort into it as he had into his war books.

Harvey Kurtzman scripted two sequences for the strip, with portions pencilled by Frank Frazetta.

Harvey Kurtzman had long dreamed of joining the slick magazine publishing world, and had been trying to convince Gaines to publish Mad in a larger, more adult format.

Harvey Kurtzman had admired Kurtzman's Mad, and met Kurtzman in New York to express his appreciation.

Harvey Kurtzman told Kurtzman that if he were ever to leave Mad, a place would be waiting for him in the Hefner empire.

Harvey Kurtzman contacted Hefner and Gaines hired Al Feldstein to edit Mad.

Harvey Kurtzman later said that Trump was the closest he ever came to producing "the perfect humor magazine".

In 1958 Harvey Kurtzman proposed a strip to TV Guide parodying adult Western TV shows; its rejection particularly disappointed him.

Harvey Kurtzman proposed a book of original material designed for the format, which Ian Ballantine, with reservations, accepted on faith out of respect for Harvey Kurtzman.

Harvey Kurtzman's Jungle Book was the first mass-market paperback of original comics content in the United States, and to Kurtzman biographer Denis Kitchen was a precursor to the graphic novel.

Whereas his Mad stories had been aimed at an adolescent audience, Harvey Kurtzman made Jungle Book for adults, which was unusual in American comics.

Harvey Kurtzman had "The Grasshopper and the Ant" printed in Esquire magazine in 1960.

The actual target of the strip had however been Hefner, who loved it; Harvey Kurtzman began working for Hefner again soon after.

Harvey Kurtzman approached Hefner in 1960 with the idea of a comic strip feature for Playboy that would star Goodman Beaver.

Harvey Kurtzman participated in a number of film projects beginning in the late 1960s.

Harvey Kurtzman wrote, co-directed, and designed several short animated pieces for Sesame Street in 1969; he was particularly proud of the Phil Kimmelman-animated Boat, in which a left prosthetic-legged sea captain voiced by Hal Smith orders a series of increasingly larger numerals to load into a boat, eventually sinking it.

Harvey Kurtzman turned down a number of well-paying opportunities in the 1970s.

The magazine's staff revered Harvey Kurtzman and had published a parody of Mad in 1971 that included "Citizen Gaines", a piece critical of Gaines' handling of Mad and treatment of Harvey Kurtzman.

Harvey Kurtzman turned the offer down, as he felt out of step with the younger cartoonists' approach.

Harvey Kurtzman turned down an offer from Rene Goscinny in 1973 to act as the US agent for the French comics magazine Pilote.

Harvey Kurtzman had no earlier teaching experience and found the prospect daunting, but Eisner convinced him to take the job.

Eisner's class was called "Sequential Art" and Harvey Kurtzman's was "Satirical Cartooning", which focused on single-panel gag cartooning.

Harvey Kurtzman had a soft touch with his students, and was well respected and well liked.

Harvey Kurtzman frequently had professional cartoonists appear as guest lecturers.

Harvey Kurtzman found he had a following in Europe; his work appeared there for the first time in the French magazine Charlie Mensuel in October 1970, and in 1973 the European Academy of Comic Book Art awarded him its Lifetime Achievement Award for 1972.

The comics industry's Harvey Kurtzman Award was named in his honor in 1988.

Harvey Kurtzman toured and gave speeches frequently to fans in the 1980s.

Harvey Kurtzman had reconciled with Gaines by the mid-1980s, and in collaboration with Elder, illustrated 19 pieces and covers for Mad from 1986 to 1989.

Harvey Kurtzman brought Little Annie Fanny to an end in 1988, amid failing health, a poor relationship with Playboy cartoon editor Michelle Urry, and resentment over the discovery that he did not own the rights to the strip.

Harvey Kurtzman's Strange Adventures assembled a wide cast of cartoonists in 1990 to illustrate stories from Kurtzman's layouts, though the book was not a success, nor was a revival of Two-Fisted Tales.

Harvey Kurtzman had long planned to write a comics history, but other work had taken priority.

Harvey Kurtzman, who had suffered from Parkinson's disease and colon cancer in later life, died at Mount Vernon, New York on February 21,1993, of complications from liver cancer, nine months after Bill Gaines' death.

Harvey Kurtzman had an unassuming demeanor; humorist Roger Price likened him to "a beagle who is too polite to mention that someone is standing on his tail".

Harvey Kurtzman's work allowed him to be at home with his children during the day, and he gave them much of his attention.

Harvey Kurtzman described this style as "abstract and telepathic" in stories that were realistic in the telling, but in which "his figures were exaggerated and contorted, demonstrations of posture as drama rather than reality as perceived".

Many liken Harvey Kurtzman's working method to that of an auteur.

In developing stories in this way Harvey Kurtzman aimed to reach a balance between text and graphics.

Harvey Kurtzman developed a way of creating stories incrementally, beginning with a paragraph-long treatment of the story.

Harvey Kurtzman proceeded to revise repeatedly on tracing paper, tacking one layer on top of another, as he worked out "what characters have to say".

Harvey Kurtzman prepared layouts on large pieces of vellum to pass on to the artists, with supplemental photographs and drawings, and personally led the artist through the story before the finished artwork was begun.

Typically when working on Little Annie Fanny, after researching the background story, Harvey Kurtzman prepared a penciled layout on Bristol board a color guide for Elder on an.

Harvey Kurtzman then traced this onto another sheet of vellum, or more if still unsatisfied with the results.

Harvey Kurtzman would pass this on to Elder to render the final image following Kurtman's layouts exactly after having the image transferred to illustration board.

Harvey Kurtzman's layouts owed considerable debt to Will Eisner's work on The Spirit.

Harvey Kurtzman derived a chiaroscuro technique from Milt Caniff in his 1940s studio work.

Harvey Kurtzman acted as mentor to a large number of cartoonists, such as Terry Gilliam, Robert Crumb, and Gilbert Shelton.

Harvey Kurtzman was a master of composition, tone and visual rhythm, both within the panel and among the panels comprising the page.

Harvey Kurtzman was able to convey fragments of genuine humanity through an impressionistic technique that was fluid and supple.