1.

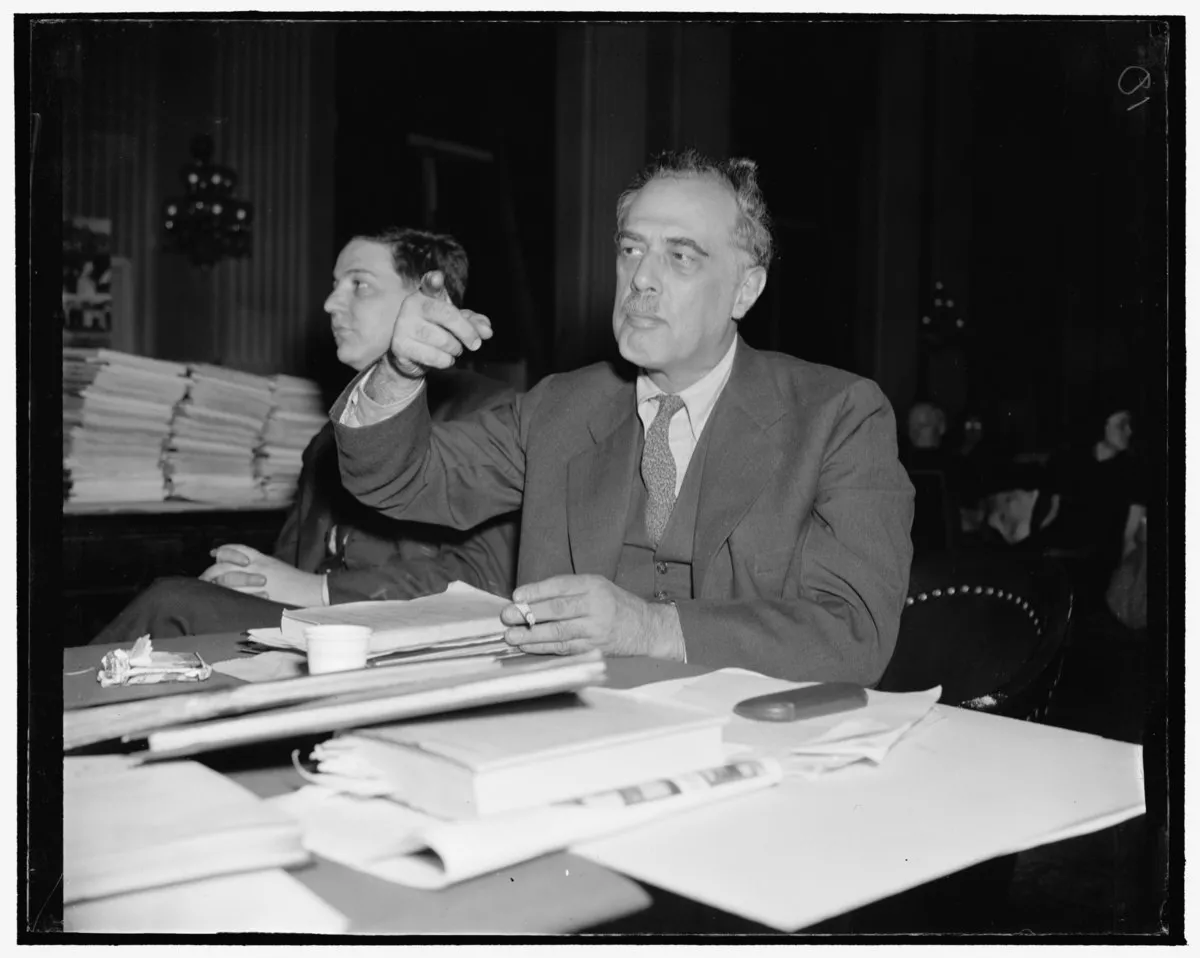

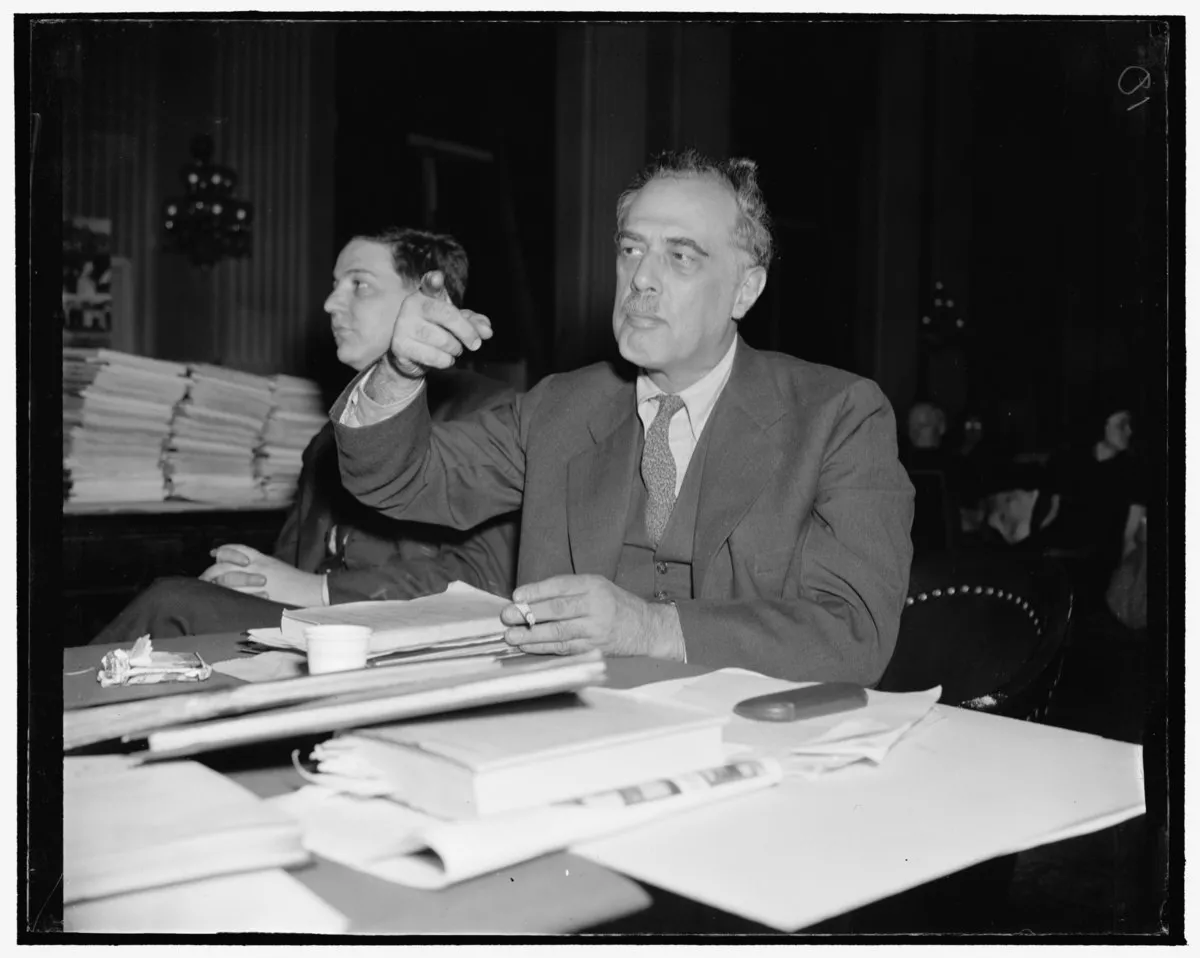

1. Henry Garfield Alsberg was an American journalist and writer who served as the founding director of the Federal Writers' Project.

1.

1. Henry Garfield Alsberg was an American journalist and writer who served as the founding director of the Federal Writers' Project.

Henry Alsberg spent years traveling through war-torn Europe on behalf of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee.

Henry Alsberg's parents were secular Jews, his mother being indifferent to religion and his father described as "aggressive in his agnosticism".

Henry Alsberg attended a shul only once as a child, when his grandmother took him to Temple Emanu-El, which infuriated his father.

Henry Alsberg suffered from lifelong digestive problems, possibly related to an incident in his teens when his appendix ruptured in the middle of the night.

Henry Alsberg waited till morning to tell his family rather than wake them up, and had emergency abdominal surgery.

Henry Alsberg, called Hank by friends and family, entered Columbia University at age 15 in 1896, the youngest member of the class of 1900, who called themselves the "Naughty-Naughtians".

Henry Alsberg was an editor of the literary magazine The Morningside, and contributed poems and short stories.

Henry Alsberg belonged to the Societe Francaise and the Philharmonic Society, and participated in baseball, wrestling, and fencing.

Henry Alsberg played two seasons on both the college and varsity football teams as guard and tackle.

Uninterested in finishing his graduate studies at Harvard or practicing law, Henry Alsberg moved back to New York City to write.

Henry Alsberg sent an early play to Paul Kester, who recommended it to Bertha Galland.

Henry Alsberg sold a short story, "Soiree Kokimono", to The Forum in 1912; the story was selected for the following year's Forum Stories compilation.

Henry Alsberg wrote up the results of his investigation in an article published in the New York Sunday World.

Henry Alsberg began writing for the New York Evening Post in 1913, as well as its sister publication The Nation.

Henry Alsberg went to London where he began working as a roving foreign correspondent for The Nation, New York World, and London's Daily Herald.

Henry Alsberg took charge of the embassy's efforts to aid Armenians and Jews, which put him in contact with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee.

On his return to the states, Henry Alsberg met with Secretary of State Robert Lansing to brief him on conditions in Constantinople and offered a plan for separating the Ottoman Empire from the German Alliance, which Lansing passed on to Woodrow Wilson.

The next day, former Ambassador Henry Alsberg Morgenthau suggested a similar plan to Lansing.

In 1917, Henry Alsberg taught a course on the socialist-inspired cooperative movement at the Rand School of Social Science, while again writing for Evening Post and The Nation.

In Jan 1919, Henry Alsberg was secretary of the Palestine Restoration Fund Campaign's National Finance Commission, and wrote for The Maccabaean, the official organ of the Zionist Organization of America.

Later in 1919, Henry Alsberg returned to Europe as a foreign correspondent for The Nation.

Henry Alsberg attended the Peace Conference in Paris as attache to the Zionist delegation.

Henry Alsberg described the period after the Russian Revolution and World War I as "the emergence of many minor nationalities, all imbued with grand imperialistic passions, fighting for their independence in a condition of economic wretchedness and moral degradation".

Henry Alsberg spent four years in various countries, including the "bandit-ridden Ukraine".

Henry Alsberg's first stop was the new country of Czechoslovakia, where he set up programs in Prague to help refugees.

Henry Alsberg continued his reporting for The Nation, the London Herald, and the New York World, bringing the anti-Semitism he was observing to international attention.

In September 1919, Henry Alsberg arrived at Kamianets-Podilskyi, which was being fought over by the Bolsheviks, the White Army, and the Ukrainian Independence Movement.

Henry Alsberg went to Odessa and on to Kiev with Allied military officers, where he reported on the pogroms, the terrorism by the Cossacks, and the atrocities of the Bolsheviks.

In January 1920, Henry Alsberg traveled north, intending to make his way to Moscow; "a believer in the utopia promised by a classless society, [he] wanted to witness and write about those ideals made manifest".

In Goldman's autobiography, she noted that Henry Alsberg was particularly affected by the stories that the townspeople in Fastov told them of the pogroms.

Henry Alsberg managed to get the police agent who escorted him to Moscow drunk on the trip.

Henry Alsberg continued his association with and work for the JDC, working in Italy with refugees.

Henry Alsberg was in Moscow during the Kronstadt rebellion, an event which brought him to condemn the Bolshevik regime in the article "Russia: Smoked Glass vs Rose-Tint" in The Nation.

American Max Eastman responded in The Liberator, calling it "journalistic emotionalizing" and declaring Henry Alsberg was "a petit-bourgeois liberal".

Henry Alsberg's article was reprinted in New York Call and reported on the front page of the New York Tribune.

The JDC hired Henry Alsberg to write a history of their organization in 1923, which was his first paid work for them.

Henry Alsberg became involved in the theater during the early 1920s.

In 1924, Alsberg obtained the English translation rights to S Ansky's The Dybbuk, written in Yiddish.

Henry Alsberg would continue to earn from productions of his adaptation of The Dybbuk throughout his life.

George Gershwin asked Henry Alsberg to act as librettist on an opera adaptation of The Dybbuk, to open at the Metropolitan Opera, but was unable to obtain the musical rights.

Henry Alsberg was particularly concerned about the conditions of political prisoners in Russia.

Henry Alsberg tried to involve the American Civil Liberties Union in his cause, but their charter limited them to domestic issues, so ACLU co-founder Roger Baldwin and Alsberg formed the International Committee for Political Prisoners, enlisting people such as Frankfurter, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, W E B Du Bois, and Carlo Tresca.

Henry Alsberg later gathered material for and edited Political Persecution Today and The Fascist Dictatorship for the ICPP.

Henry Alsberg spent several years traveling in Europe and working on his own writing, including his autobiography which he never finished.

Henry Alsberg then took on editing two magazines for the agency.

At the time, Henry Alsberg dubbed himself a "philosophical anarchist" although others labelled him a "tired radical of the 20s".

Henry Alsberg was not selected as director of the Writers' Project because of any administrative or managerial skill, but rather because of his understanding of the project's purpose and his insistence on high editorial standards for the project's products.

Henry Alsberg came to the Writers' Project with a "visionary sense of its potential to join social reform with the democratic renaissance of American letters".

Henry Alsberg insisted that the American Guide Series be much more than an American Baedeker; the guides needed to capture the whole of American civilization and culture and celebrate the diversity of the nation.

Henry Alsberg required that each state project include ethnography with particular attention to Native Americans and African Americans, and that the front third of every guide contain essays on local culture, history, economics, etc.

Two of the writers Henry Alsberg personally recruited to the Writers' Project were John Cheever and Conrad Aiken.

Henry Alsberg felt the American Guide Series needed to be supplemented with books about the people of the country.

One of Henry Alsberg's letters describes the approach that he wanted the ethnic studies writers to take:.

When Henry Alsberg threw a cocktail party to celebrate the publication of the Washington guide, Henry Alsberg and the Writers' Project were attacked on the Senate floor by Mississippi's Senator Bilbo in a tirade because a woman from his own state had been invited to a party that had both white and black guests.

Henry Alsberg struggled with the project's tension between providing jobs and creative works.

The American Guide Series was a necessary product to justify the project's existence, but Henry Alsberg sympathized with the many writers who chafed at being confined to writing guidebooks and secretly allowed some project writers to focus on their own creative writing.

Henry Alsberg quietly attempted to put out a literary magazine, but the single issue was subject to bickering and resistance from the Writers Union.

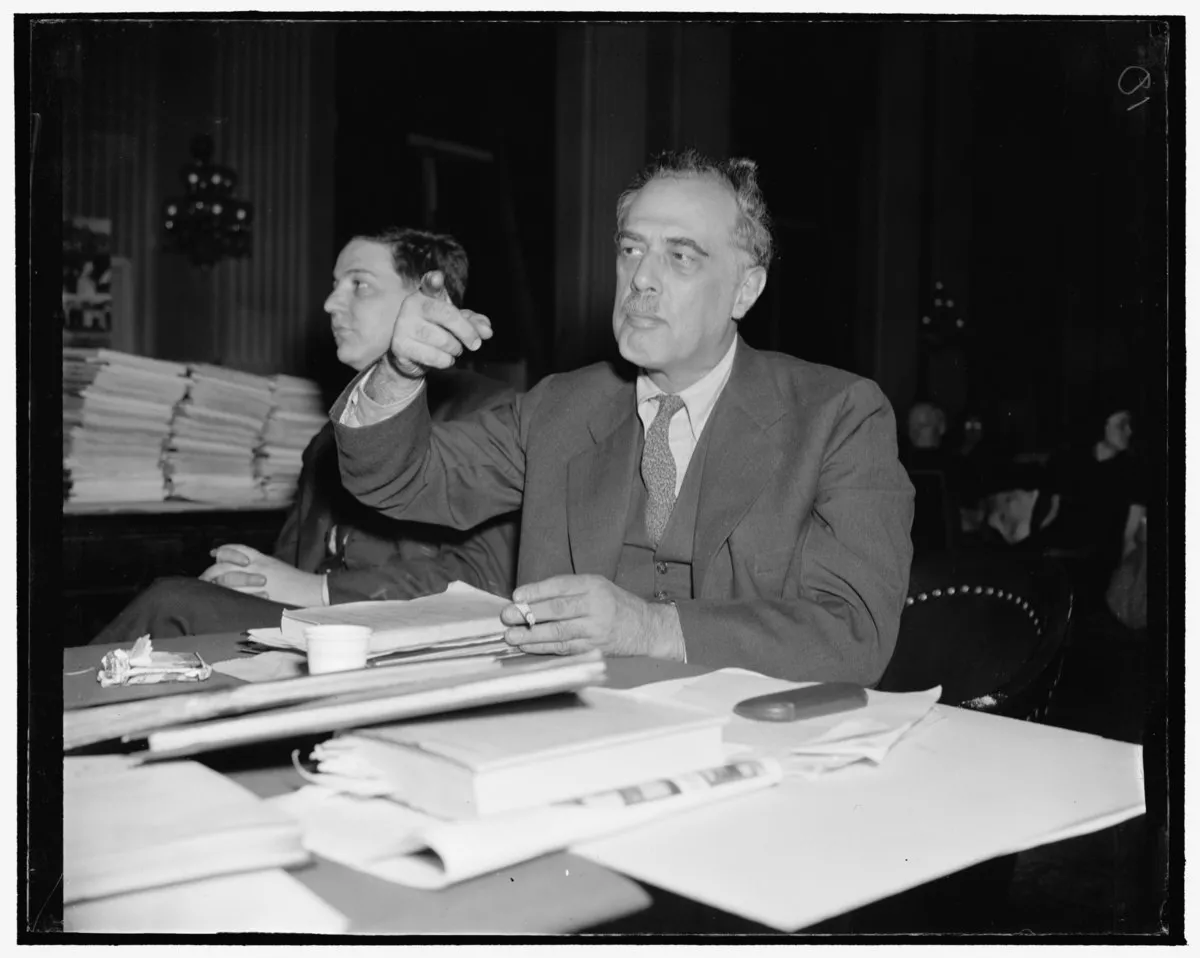

Henry Alsberg was called to testify before the committee December 6,1938, after months of requesting a hearing.

The FWP was then investigated by Clifton Woodrum's House subcommittee on appropriations, which attacked a letter to the editor Henry Alsberg had written ten years previously about conditions in prisons.

Henry Alsberg refused to resign immediately, continuing to work on state sponsorships and works in progress.

Henry Alsberg continued with his political writing, including a piece calling for "an all-out effort to defeat the Axis", and worked on a book that would never be published.

In 1942, Henry Alsberg was hired to work at the Office of War Information.

Henry Alsberg began work on his book, Let's Talk About the Peace, which would be published after the war in 1945.

Henry Alsberg took on a project for Hastings House Publishers as editor-in-chief for a one-volume version of the American Guide Series.

Henry Alsberg's condensed American Guide series was published in 1949 as The American Guide, and was featured in the Book of the Month Club.

Henry Alsberg continued as an editor at Hastings House for more than a decade.

Some of Henry Alsberg's papers are archived at the libraries at the University of Oregon.