1.

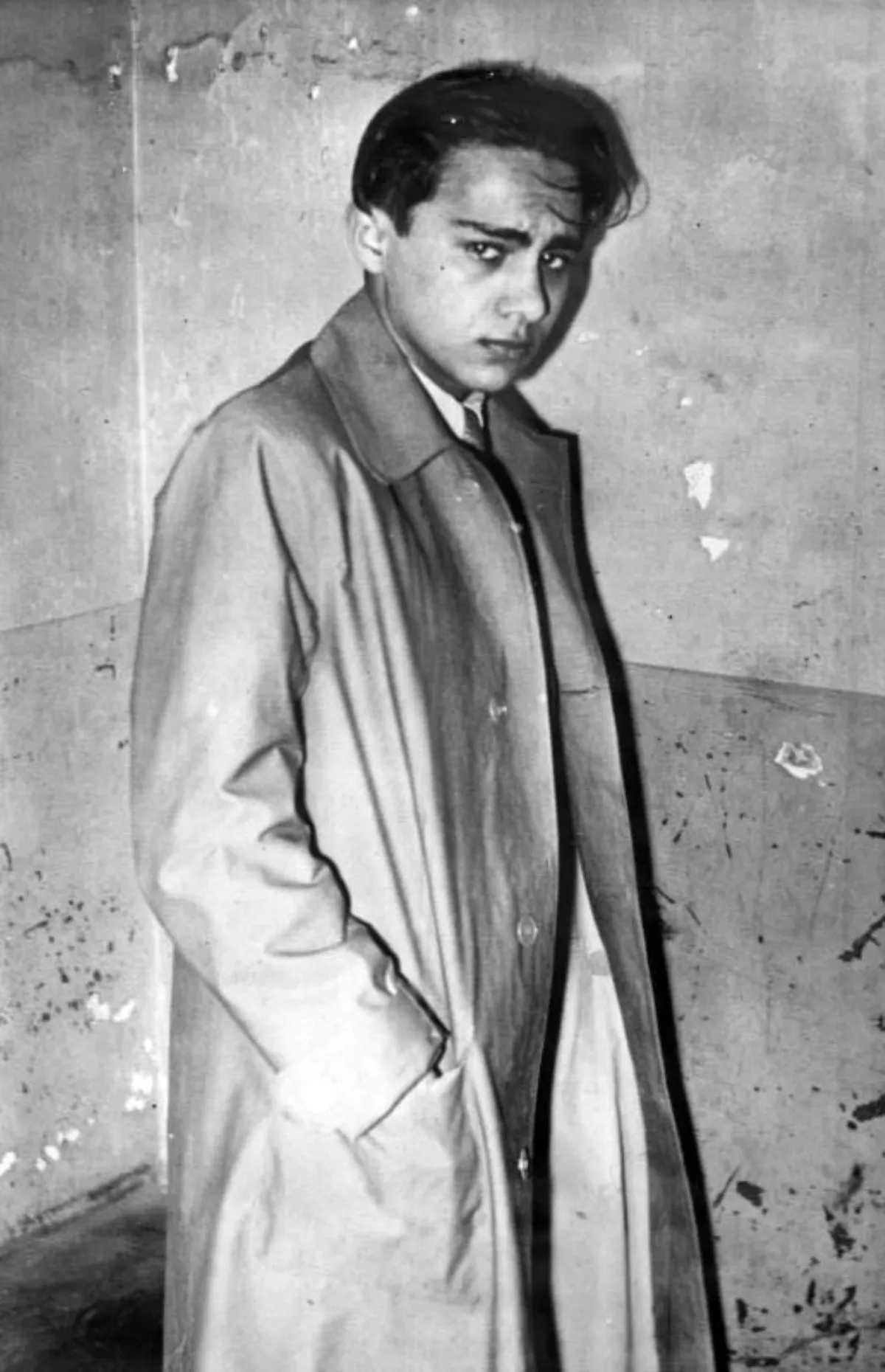

1. Herschel Feibel Grynszpan was a Polish-Jewish expatriate born and raised in Weimar Germany who shot and killed the German diplomat Ernst vom Rath on 7 November 1938 in Paris.

1.

1. Herschel Feibel Grynszpan was a Polish-Jewish expatriate born and raised in Weimar Germany who shot and killed the German diplomat Ernst vom Rath on 7 November 1938 in Paris.

However, this remains a matter of dispute: Kurt Grossman claimed in 1957 that Herschel Grynszpan lived in Paris under another identity.

Herschel Grynszpan was born on 28 March 1921 in Hanover, Germany.

Herschel Grynszpan was the youngest of six children, only three of whom survived childhood.

The Herschel Grynszpan family was known as Ostjuden by the Germans and many West European Jews.

Herschel Grynszpan was considered by his teachers to be intelligent, if rather lazy, a student who never seemed to try to excel at his studies.

Herschel Grynszpan later complained that his teachers disliked him because he was an Ostjude, and he was treated as an outcast by his German teachers and fellow students.

Herschel Grynszpan attended a state primary school until 1935 and later said that he left school because Jewish students were already facing discrimination.

Herschel Grynszpan was an intelligent, sensitive and easily-provoked youth whose few close friends found him too touchy.

Herschel Grynszpan was an active member of the Jewish youth sports club, Bar-Kochba Hanover.

Herschel Grynszpan obtained a Polish passport and German residence permit and received permission to leave Germany and go to Belgium, where another uncle lived.

Herschel Grynszpan did not intend to remain in Belgium and entered France illegally in September 1936.

Herschel Grynszpan met few people outside it, learning only a few words of French in two years.

Herschel Grynszpan initially lived a carefree, bohemian life as a "poet of the streets", spending his days aimlessly wandering and reciting Yiddish poems to himself.

Herschel Grynszpan spent this period unsuccessfully trying to become a legal resident of France because he could not work nor study legally.

Herschel Grynszpan became a stateless person as a result, and continued to live illegally in Paris.

Herschel Grynszpan was afraid to accept a job because of his illegal immigrant status and depended for support on his uncle Abraham, who was extremely poor.

Herschel Grynszpan's refusal to work caused tension with his uncle and aunt, who frequently told him that he was a drain on their finances and had to take a job despite the risk of deportation.

Herschel Grynszpan came from a close-knit, loving family, and often spoke about his love for his family and how much he missed them.

The Herschel Grynszpan family was among the estimated 12,000 Polish Jews arrested, stripped of their property, and herded aboard trains headed for Poland.

On 6 November 1938, Herschel Grynszpan asked his uncle Abraham to send money to his family.

Herschel Grynszpan went to a gun shop in the Rue du Faubourg St Martin, where he bought a 6.35mm revolver and a box of 25 bullets for 235 francs.

Herschel Grynszpan caught the metro to the Solferino station and walked to the German embassy at 78 Rue de Lille.

At 9:45 am, Herschel Grynszpan identified himself as a German resident at the reception desk and asked to see an embassy official; he did not ask for anyone by name.

Herschel Grynszpan claimed to be a spy with important intelligence which he had to give to the most senior diplomat available, preferably the ambassador.

Unaware that he had just walked past von Welczeck, Herschel Grynszpan asked if he could see "His Excellency, the ambassador" to hand over the "most important document" he claimed to have.

When Herschel Grynszpan entered vom Rath's office, vom Rath asked to see the "most important document".

Herschel Grynszpan pulled out his gun, and shot him five times in the abdomen.

Herschel Grynszpan made no attempt to resist or escape, and identified himself truthfully to the French police.

Herschel Grynszpan confessed to shooting vom Rath, and repeated that his motive was to avenge the persecuted Jews.

Herschel Grynszpan was distraught when he learned that his action was used by the Nazis to justify further violent assaults on German Jews, although his family was safe from that latest manifestation of Nazi antisemitism.

Herschel Grynszpan was prepared to die when he fired those shots.

Deploring vom Rath's assassination, they said that Herschel Grynszpan had been driven to his act by the Nazi persecution of German Jews in general and his family in particular.

Herschel Grynszpan asked Jews not to donate to the fund so the Nazis could not attribute Grynszpan's defence to a Jewish conspiracy, although Jewish organizations raised money despite this.

Until Franckel and Moro-Giafferi took over his defence, it was accepted that Herschel Grynszpan went to the Embassy in a rage and shot the first German he saw as a political act to avenge the persecution of his family and all German Jews.

Herschel Grynszpan considered himself a hero who stood up to the Nazis, and believed that when his case went to trial his "Jewish avenger" defense would acquit him.

The outcome of the Schwartzbard trial in 1927, when Sholom Schwartzbard was acquitted for assassinating Symon Petliura in 1926 on the grounds that he was avenging pogroms by Ukrainian forces, was a major factor in Herschel Grynszpan's seeking the "Jewish avenger" defense.

Herschel Grynszpan was theorized to have been acquainted with vom Rath before the shooting.

When vom Rath reneged on his promise, Herschel Grynszpan went to the embassy and shot him.

Herschel Grynszpan alleged that vom Rath was nicknamed "Mrs Ambassador" and "Notre Dame de Paris" as a result of his homosexual activities.

German embassy officials were certain that Herschel Grynszpan had not asked for vom Rath by name, and saw vom Rath only because he happened to be on duty at the time.

Herschel Grynszpan claimed in 1947 that he simply invented the story as a possible line of defence, one that would put the affair in an entirely new light.

Herschel Grynszpan had just come from visiting him in his cell, and was revolted by the attitude of his client.

Soltikow was sued by vom Rath's surviving brother in 1952 for libeling his brother, and the evidence Soltikow presented to support his claims of a homosexual relationship between vom Rath and Herschel Grynszpan did not hold up in a court of law.

From November 1938 to June 1940, Herschel Grynszpan was imprisoned in the Fresnes Prison in Paris while legal arguments continued over the conduct of his trial.

Grimm tried to argue that Herschel Grynszpan should be extradited to Germany, but the French government would not agree to this.

The Germans argued that Herschel Grynszpan had acted as the agent of a Jewish conspiracy, and their fruitless efforts to find evidence to support this further delayed the trial.

Grimm and Diewerge, who were both antisemitic, were obsessed by the belief that Herschel Grynszpan had acted on behalf of unknown Jewish Hintermanner who were responsible for the assassination of Wilhelm Gustloff by David Frankfurter in 1936.

The trial had not begun and Herschel Grynszpan was still in prison when the German army approached Paris in June 1940.

Herschel Grynszpan was sent to Orleans and, by bus, to the prison at Bourges.

Herschel Grynszpan was sent to make his own way to Toulouse, where he was incarcerated.

Herschel Grynszpan had no money, knew no one in the region, and spoke little French.

Herschel Grynszpan was illegally extradited to Germany on 18 July 1940, and was interrogated by the Gestapo.

Herschel Grynszpan was delivered to Bomelburg, driven to Paris, flown to Berlin and imprisoned at Gestapo headquarters on Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse.

Herschel Grynszpan spent the rest of his life in German custody, at the Moabit prison in Berlin and in concentration camps at Sachsenhausen and Flossenburg.

Herschel Grynszpan received relatively mild treatment because Goebbels intended him to be the subject of a show trial proving the complicity of "international Jewry" in the vom Rath killing.

The Justice Ministry argued that since Herschel Grynszpan was not a German citizen, he could not be tried in Germany for a murder he had committed outside Germany; a minor at the time, he could not face execution.

Herschel Grynszpan, who had rejected the idea of using this defence when Moro-Giafferi suggested it in 1938, had apparently changed his mind.

Herschel Grynszpan told Heinrich Jagusch in mid-1941 that he intended using this defence but the Justice Ministry did not inform Goebbels, who was furious.

Herschel Grynszpan has invented the insolent argument that he had a homosexual relationship with.

The problem was their belief that vom Rath was homosexual; Herschel Grynszpan had been given details of his personal life by Moro-Giafferi in Paris, and would reveal them in court.

Herschel Grynszpan was moved in September to the prison at Magdeburg, and his fate after September 1942 is unknown.

Several authorities believe that, according to evidence, Herschel Grynszpan died at Sachsenhausen sometime in late 1942; the historical consensus is that he did not survive the war.

Soltikow wrote that he was doing a service to "World Jewry" by "proving" that Herschel Grynszpan killed vom Rath as the result of a homosexual relationship gone sour, rather than as the product of a world Jewish conspiracy.

The theory that Herschel Grynszpan was living in Paris and not being prosecuted for vom Rath's murder, despite overwhelming evidence of his guilt, would have been attractive to many Germans after the war.

In 1957 an article by German historian Helmut Heiber claimed that Herschel Grynszpan was sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp and survived the war; another article by Egon Larsen, published two years later, said that Herschel Grynszpan had changed his name, was living in Paris and was working as a garage mechanic.

Heiber's article was unmasked as based entirely on rumours that Herschel Grynszpan was alive and well in Paris.

Larsen's report was based on talks with people who claimed to have met people who knew that Herschel Grynszpan was living in Paris; despite their claims about his survival, no one had ever actually seen Herschel Grynszpan.

The only person who claimed to have seen Herschel Grynszpan was Soltikow; everyone else claimed to have talked with other people who supposedly met Herschel Grynszpan.

Heiber retracted his 1957 article in 1981, saying that he now believed that Herschel Grynszpan died during the war.

Herschel Grynszpan was declared legally dead by the West German government in 1960.

Since Herschel Grynszpan was extremely close to his parents and siblings, it is unlikely that he would not contact his parents or his brother if he were alive after the war.

Herschel Grynszpan's parents, sending him to what they thought was safety in Paris while they and his siblings remained in Germany, survived the war.

Sendel Herschel Grynszpan was present at the 1952 Israeli premiere of A Child of Our Time, Michael Tippett's oratorio inspired by vom Rath's murder and the ensuing pogrom.

Herschel Grynszpan was widely shunned during his lifetime by Jewish communities around the world, who saw him as an irresponsible, immature teenager who brought down the wrath of the Nazis in Kristallnacht.

In December 2016, a photograph found among a group of uncatalogued photos in the archives of the Jewish Museum Vienna by chief archivist, Christa Prokisch led to speculation that Herschel Grynszpan could have survived the war.

The photograph, taken at a displaced persons camp in Bamberg, Bavaria, on 3 July 1946, shows a man resembling Herschel Grynszpan participating in a demonstration by Holocaust survivors against British refusal to let them emigrate to the British mandate of Palestine.