1.

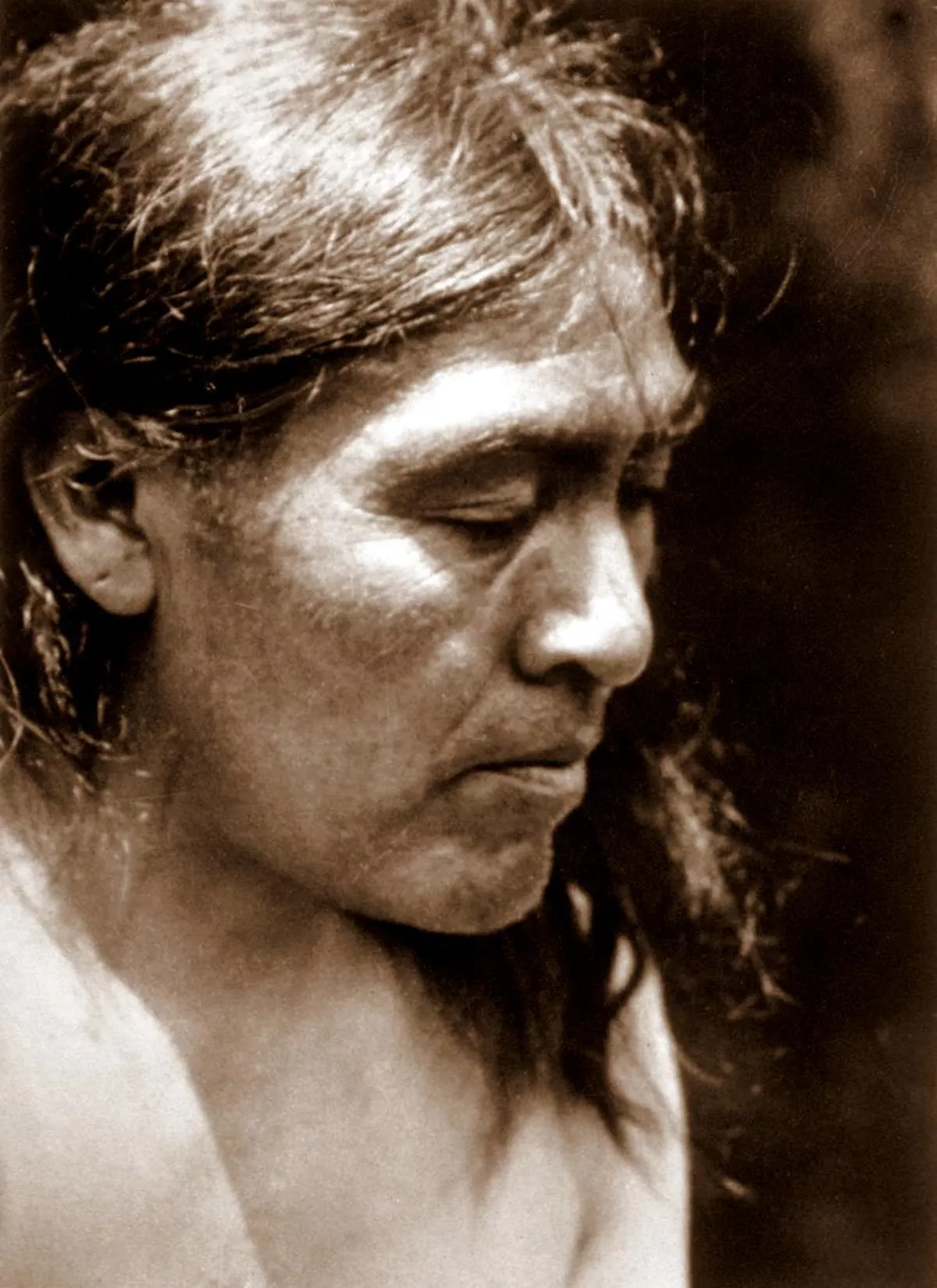

1. Widely described as the "last wild Indian" in the United States, Ishi lived most of his life isolated from modern North American culture, and was the last known Native manufacturer of stone arrowheads.

1.

1. Widely described as the "last wild Indian" in the United States, Ishi lived most of his life isolated from modern North American culture, and was the last known Native manufacturer of stone arrowheads.

Ishi, which means "man" in the Yana language, is an adopted name.

Anthropologists at the University of California, Berkeley, took Ishi in, studied him, and hired him as a janitor.

Ishi lived most of his remaining five years in a university building in San Francisco.

Ishi's life was depicted and discussed in multiple films and books, notably the biographical account Ishi in Two Worlds published by Theodora Kroeber in 1961.

Ishi was likely born in the year 1861 within the heart of Yahi and Yana territory.

When Ishi appeared near Oroville three years later, he was alone and communicated through mime that his three companions had all died, his uncle and mother by drowning.

Ishi was found pre-sunset by Floyd Hefner, son of the next-door dairy owner, who was "hanging out", and who went to harness the horses to the wagon for the ride back to Oroville, for the workers and meat deliveries.

Webber arrived, he directed Adolph Kessler, a 19-year-old slaughterhouse worker, to handcuff Ishi, who smiled and complied.

Ishi described family units, naming patterns, and the ceremonies he knew.

Ishi identified material items and showed the techniques by which they were made.

In June 1915, for three months, Ishi lived in Berkeley with Waterman and his family.

Ishi was treated by Pope, a professor of medicine at UCSF.

Pope became a close friend of Ishi, and learned from him how to make bows and arrows in the Yahi way.

Ishi believed Yahi tradition called for the body to remain intact.

Ishi's brain was preserved and his body cremated, in the mistaken belief that cremation was the traditional Yahi practice.

Kroeber sent Ishi's preserved brain to the Smithsonian Institution in 1917.

Ishi used thumb draw and release with his short bows.

Ishi had found that points made by Ishi were not typical of those recovered from historical Yahi sites.

Ishi based his conclusion on a study of the points made by Ishi, compared to others held by the museum from the Yahi, Nomlaki and Wintu cultures.

Shackley suggests that Ishi learned the skill directly from a male relative of one of those tribes.

Ishi's story has been compared to that of Ota Benga, an Mbuti pygmy from Congo.

Ishi's family had died and were not given a mourning ritual.