1.

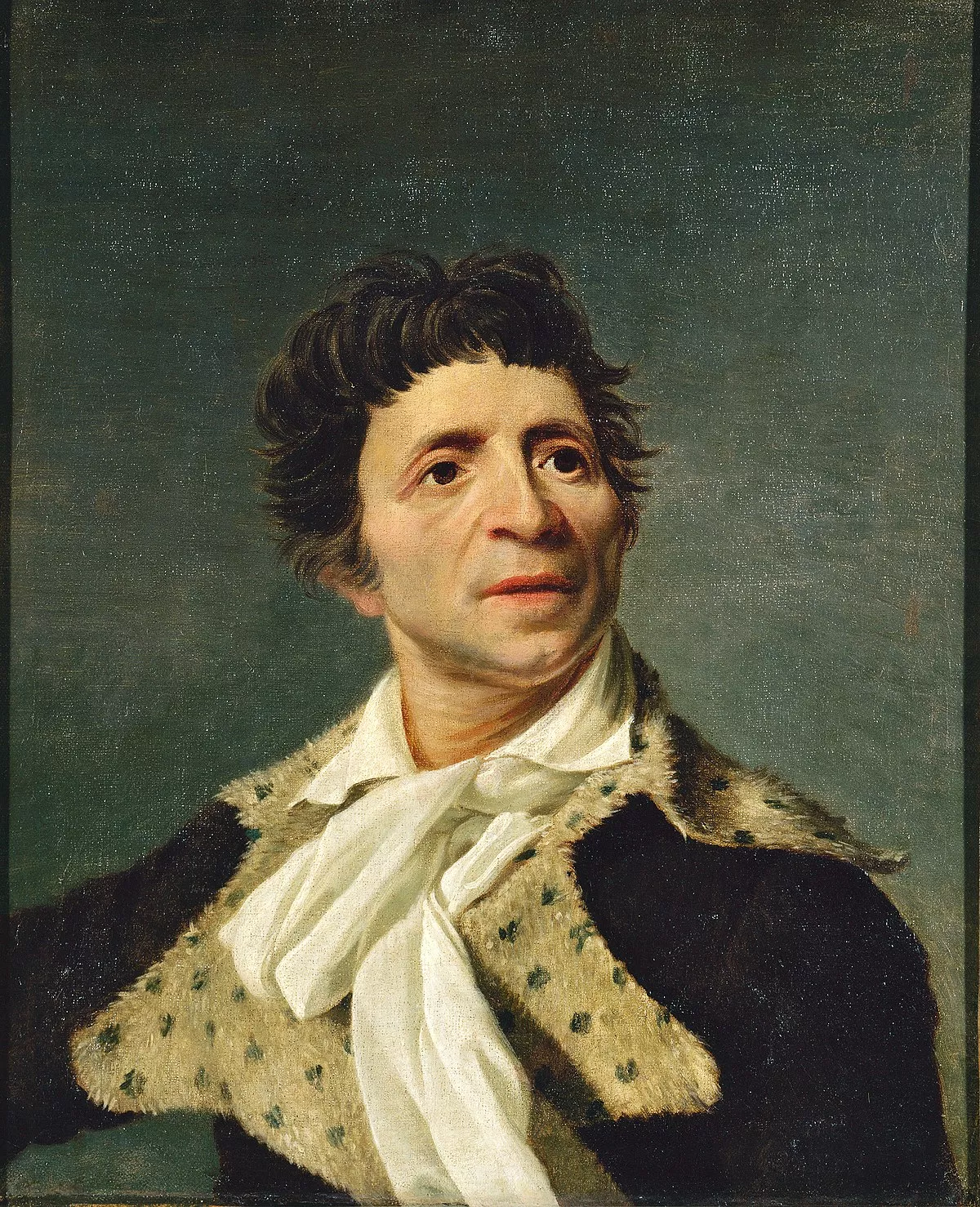

1. Jean-Paul Marat was a French political theorist, physician, and scientist.

1.

1. Jean-Paul Marat was a French political theorist, physician, and scientist.

Jean-Paul Marat's journalism was known for its fierce tone and uncompromising stance toward the new leaders and institutions of the revolution.

David and Jean-Paul Marat were part of the Paris Commune leadership anchored in the Cordeliers section, from where the Revolution is said to have started in 1789 because those who stormed the Bastille lived there.

Jean-Paul Marat's father studied in Spain and Sardinia before becoming a Mercedarian friar in 1720, at age 16, but at some point left the order and converted to Calvinism, and in 1740 immigrated to the Protestant Republic of Geneva.

Jean-Paul Marat's family lived in moderate circumstances, as his father was well educated but unable to secure a stable profession.

Jean-Paul Marat left home at the age of 16, desiring to seek an education in France.

Jean-Paul Marat was aware of the limited opportunities for those seen as outsiders as his highly educated father had been turned down for several college teaching posts.

In 1754 his family settled in Neuchatel, capital of the Principality, where Jean-Paul Marat's father began working as a tutor.

Jean-Paul Marat received his early education in the city of Neuchatel and there was a student of Jean-Elie Bertrand, who later founded the Societe typographique de Neuchatel.

Jean-Paul Marat then moved to Paris and studied medicine without gaining any formal qualifications.

Jean-Paul Marat worked, informally, as a doctor after moving to London in 1765 due to a fear of being "drawn into dissipation".

Jean-Paul Marat condemned the King's power to influence Parliament through bribery and attacked limitations on voting rights.

Jean-Paul Marat suggests that the people express sovereignty through representatives who cannot enact legislation without the approval of the people they represent.

Jean-Paul Marat published "A Philosophical Essay on Man," in 1773 and "Chains of Slavery," in 1774.

Voltaire's sharp critique of "De l'Homme", partly in defence of his protege Helvetius, reinforced Jean-Paul Marat's growing sense of a widening gulf between the philosophes, grouped around Voltaire on one hand, and their opponents, loosely grouped around Rousseau on the other.

Jean-Paul Marat published Enquiry into the Nature, Cause, and Cure of a Singular Disease of the Eyes on his return to London.

In 1776, Jean-Paul Marat moved to Paris after stopping in Geneva to visit his family.

Jean-Paul Marat set up a laboratory in the Marquise de l'Aubespine's house with funds obtained by serving as court doctor among the aristocracy.

Jean-Paul Marat's method was to describe in detail the meticulous series of experiments he had undertaken on a problem, seeking to explore and then exclude all possible conclusions but the one he reached.

Jean-Paul Marat published works on fire and heat, electricity, and light.

Jean-Paul Marat published a summary of his scientific views and discoveries in Decouvertes de M Marat sur le feu, l'electricite et la lumiere in 1779.

Jean-Paul Marat published three more detailed and extensive works that expanded on each of his areas of research.

Jean-Paul Marat then published his work, with the claim that the Academy approved of its contents.

The focus of Jean-Paul Marat's work was the study of how light bends around objects, and his main argument was that while Newton held that white light was broken down into colours by refraction, the colours were actually caused by diffraction.

Jean-Paul Marat sought to demonstrate that there are only three primary colours, rather than seven as Newton had argued.

Once again, Jean-Paul Marat requested the Academy of Sciences review his work, and it set up a commission to do so.

Jean-Paul Marat addressed a number of other areas of enquiry in his work, concluding with a section on lightning rods which argued that those with pointed ends were more effective than those with blunt ends, and denouncing the idea of "earthquake rods" advocated by Pierre Bertholon de Saint-Lazare.

Apart from his major works, during this period Jean-Paul Marat published shorter essays on the medical use of electricity and on optics.

Jean-Paul Marat published a well-received translation of Newton's Opticks, which was still in print until recently, and later a collection of essays on his experimental findings, including a study on the effect of light on soap bubbles in his Memoires academiques, ou nouvelles decouvertes sur la lumiere.

In 1780, Jean-Paul Marat published his "favourite work," a Plan de legislation criminelle.

Jean-Paul Marat was inspired by Rousseau and Cesare Beccaria's "Il libro dei delitti e delle pene".

Jean-Paul Marat strongly desired to contribute his ideas to the coming events and subsequently abandoned his career as a scientist and doctor, taking up his pen on behalf of the Third Estate.

Jean-Paul Marat claimed that this work caused a sensation throughout France, though he likely exaggerated its effect as the pamphlet mostly echoed ideas similar to many other pamphlets and cahiers circulating at the time.

Jean-Paul Marat argues for a constitutional monarchy, believing that a republic is ineffective in large nations.

Jean-Paul Marat was not directly involved in the Fall of the Bastille but sought to glorify his role that day by claiming that he had intercepted a group of German soldiers on Pont Neuf.

Jean-Paul Marat faced the problem of counterfeiters distributing falsified versions of L'Ami du peuple.

Between 1789 and 1792, Jean-Paul Marat was often forced into hiding, sometimes in the Paris sewers, where he almost certainly aggravated his debilitating chronic skin disease.

Jean-Paul Marat was the sister-in-law of his typographer, Jean-Antoine Corne, and had lent him money and sheltered him on several occasions.

Jean-Paul Marat was said by Stanley Loomis to have claimed the position of its head.

Ernest Belfort Bax disputed this claim, saying that on appearing in the upper daylight of Paris, Jean-Paul Marat was almost immediately invited to assist the new governing body with his advice, and had a special tribune assigned to him.

Jean-Paul Marat was thus assiduous in his attendance at the Commune, although never formally a member.

Actually the Committee, of which Jean-Paul Marat was one of the most influential members, took the step of withdrawing from the prisons those of whose guilt, in its opinion, there was any reasonable doubt.

Jean-Paul Marat himself did not participate in the violence of the massacres, but rather the Sections of Paris had begun to act of themselves.

Whether Jean-Paul Marat played a part in the cause of the massacres is still continually debated.

Maximilien Robespierre, Danton and Jean-Paul Marat all stressed the necessity of a tribunal that would judge these crimes.

Jean-Paul Marat had long foreseen and foretold what would happen if foreign invasion found Paris in a state of chaos.

Jean-Paul Marat declared it unfair to accuse Louis of anything before his acceptance of the French Constitution of 1791, and although implacably, he said, believing that the monarch's death would be good for the people, defended Guillaume-Chretien de Lamoignon de Malesherbes, the King's counsel, as a "sage et respectable vieillard".

Jean-Paul Marat cried that France needed a chief, "a military Tribune".

The Girondins fought back and demanded that Jean-Paul Marat be tried before the Revolutionary Tribunal.

Jean-Paul Marat decisively defended his actions, stating that he had no evil intentions directed against the Convention.

Jean-Paul Marat was acquitted of all charges to the celebration of his supporters.

Jean-Paul Marat asked her what was happening in Caen and she explained, reciting a list of the offending deputies.

The extreme decomposition of Jean-Paul Marat's body made any realistic depiction impossible, and David's work beautified the skin that was discoloured and scabbed from his chronic skin disease in an attempt to create antique virtue.

Jean-Paul Marat's heart was embalmed separately and placed in an urn in an altar erected to his memory at the Cordeliers to inspire speeches that were similar in style to Marat's journalism.

Jean-Paul Marat continued to be held in high regard in the Soviet Union.

Jean-Paul Marat became a common name, and Jean-Paul Marat Fjord in Severnaya Zemlya was named after him.

Jean-Paul Marat was sick with it for the three years prior to his assassination, and spent most of this time in his bathtub.