1.

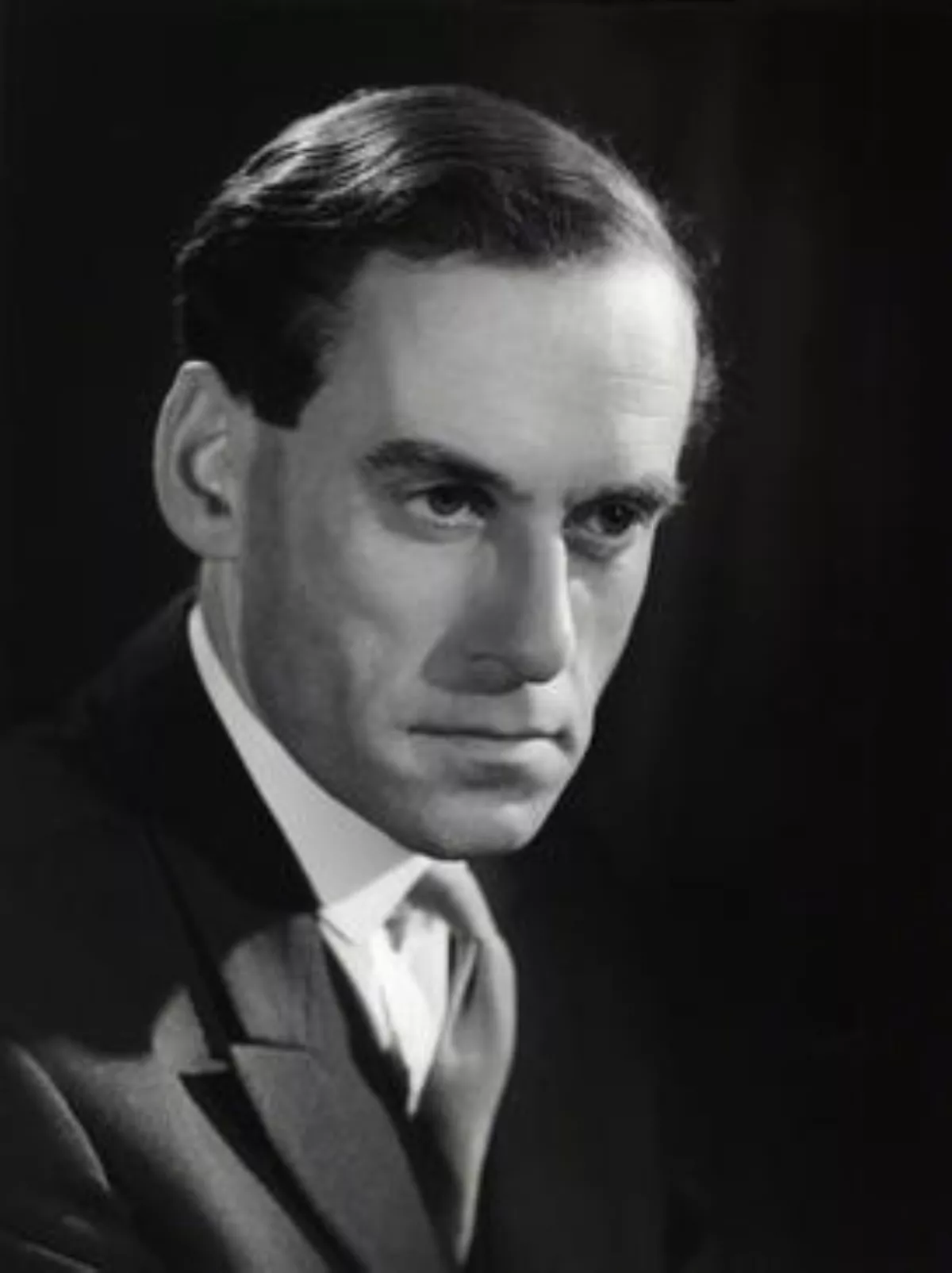

1. John Jeremy Thorpe was a British politician who served as the Member of Parliament for North Devon from 1959 to 1979 and as leader of the Liberal Party from 1967 to 1976.

1.

1. John Jeremy Thorpe was a British politician who served as the Member of Parliament for North Devon from 1959 to 1979 and as leader of the Liberal Party from 1967 to 1976.

Jeremy Thorpe was the son and grandson of Conservative MPs, but decided to align with the small and ailing Liberal Party.

Jeremy Thorpe entered Parliament at the age of 30, rapidly made his mark, and was elected party leader in 1967.

Under the first-past-the-post electoral system this gave them only 14 seats, but in a hung parliament, no party having an overall majority, Jeremy Thorpe was in a strong position.

Jeremy Thorpe was offered a cabinet post by the Conservative prime minister, Edward Heath, if he would bring the Liberals into a coalition.

Jeremy Thorpe resigned the leadership in May 1976 when his position became untenable.

Jeremy Thorpe was born in South Kensington, London, on 29 April 1929.

Jeremy Thorpe's father was John Henry Thorpe, a lawyer and politician who was the Conservative MP for Manchester Rusholme between 1919 and 1923.

The more recent Jeremy Thorpe ancestors were Irish, stemming from the elder of two brothers who were, according to family tradition, soldiers under Cromwell during the re-conquest of Ireland.

Jeremy Thorpe's great-grandfather, William Thorpe, was a Dublin policeman who, having been a labourer, joined the police as a constable and rose to the rank of superintendent.

One of his many sons, John Jeremy Thorpe, became an Anglican priest and served as Archdeacon of Macclesfield from 1922 to 1932.

Jeremy Thorpe's upbringing was privileged and protected, under the care of nannies and nursemaids until, in 1935, he began attending Wagner's day school in Queen's Gate.

Jeremy Thorpe became a proficient violinist, and often performed at school concerts.

In January 1938 Jeremy Thorpe went to Cothill House, a school in Oxfordshire that prepared boys for entry to Eton.

War began in September 1939; in June 1940, with invasion threatening, the Jeremy Thorpe children were sent to live with their American aunt, Kay Norton-Griffiths, in Boston.

Jeremy Thorpe remained there for three generally happy years; his main extracurricular task, he later recalled, was looking after the school's pigs.

Jeremy Thorpe proved an indifferent scholar, he lacked sporting aptitude, and although superficially a rebel against conformity, his frequent toadying to authority earned him the nickname "Oily Thorpe".

Jeremy Thorpe offended the school's traditionalists by resigning from the school's cadet force, and shocked others by expressing his intention to marry Princess Margaret, then second in line to the British throne.

Jeremy Thorpe was reading Law, but his primary interests at Oxford were political and social.

Jeremy Thorpe was quick to seek political office, initially in the Oxford University Liberal Club which, despite the doldrums affecting the Liberal Party nationally, was a thriving club with over 800 members.

Jeremy Thorpe was elected to the club's committee at the end of his first term; in November 1949 he became its president.

Outside Oxford, Jeremy Thorpe showed a genuine commitment to Liberalism in his enthusiastic contributions to the party's national election campaigns, and on reaching his 21st birthday in April 1950, applied to have his name added to the party's list of possible parliamentary candidates.

Beyond the OULC, Jeremy Thorpe achieved the presidency of the Oxford University Law Society, although his principal objective was the presidency of the Oxford Union, an office frequently used as a stepping-stone to national prominence.

Normally, would-be presidents first served in the Union's junior offices, as Secretary, Treasurer or Librarian, but Jeremy Thorpe, having impressed as a confident and forceful debater, decided early in 1950 to try directly for the presidency.

Jeremy Thorpe was easily defeated by the future broadcaster Robin Day.

The time-consuming nature of his various offices meant that Jeremy Thorpe required a fourth year to complete his law studies, which ended in the summer of 1952 with a third-class honours degree.

At Oxford, Jeremy Thorpe enjoyed numerous friendships with his contemporaries, many of whom later achieved distinction.

Jeremy Thorpe was adopted as North Devon's Liberal candidate in April 1952.

Jeremy Thorpe spent much of his spare time cultivating the voters in North Devon; at rallies and on the doorstep he mixed local concerns with conspicuously liberal views on larger, international issues such as colonialism and apartheid.

Jeremy Thorpe succeeded in halving the Conservative majority in the constituency, and restoring the Liberals to second place.

In need of a paid occupation Jeremy Thorpe opted for the law, and in February 1954 was called to the bar in the Inner Temple.

Jeremy Thorpe was employed by Associated-Rediffusion, at first as chairman of a science discussion programme, The Scientist Replies, and later as an interviewer on the station's major current affairs vehicle This Week.

Jeremy Thorpe, who had figured prominently in the Torrington campaign, saw this victory in an adjoining Devon constituency as a harbinger of his own future success.

Jeremy Thorpe highlighted poor communications as the principal reason for the lack of employment opportunities in North Devon, and called for urgent government action.

Jeremy Thorpe championed freedom from colonial and minority rule, and was an outspoken opponent of regimes he considered oppressive such as those in South Africa and the short-lived Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

Jeremy Thorpe was noted for his verve and wit; when in 1962, after a series of by-election disasters, Macmillan sacked a third of his cabinet, Thorpe's reported comment, an inversion of the biblical verse John 15:13, was "Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his friends for his life".

In North Devon, Jeremy Thorpe increased his personal majority to over 5,000.

Jeremy Thorpe proved to be an excellent fund-raiser, although his insistence on personal control of much of the party's funds aroused criticism and resentment.

In July 1965, after the end of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, Jeremy Thorpe toured Central and East Africa, visiting both Zambia and Rhodesia.

Jeremy Thorpe suffered a personal disappointment in North Devon, where his majority dropped to 1,166.

Jeremy Thorpe was now the senior Liberal MP after Grimond, and the party's highest-profile member, although Tim Beaumont, chairman of the party's organising committee, noted in his diary: "I am pretty certain that he has little popularity within the Parliamentary Party".

The 12 Liberal MPs formed the whole electorate; after the first ballot, Jeremy Thorpe had secured six votes against three each for Eric Lubbock, the Orpington MP, and Emlyn Hooson who had succeeded to the Montgomeryshire seat.

Jeremy Thorpe reacted strongly against bone-headed Establishment snobbery, arrogant management or racial injustice, but showed scant interest in formulating any coherent political philosophy.

Discontent against Jeremy Thorpe's leadership was being voiced within a year of his election, culminating in June 1968 when disaffected senior party members combined with Young Liberals in an attempt to depose him.

Jeremy Thorpe had just married Caroline Allpass, and was abroad on honeymoon when the plotters struck.

Jeremy Thorpe's marriage provided him with a period of emotional stability; a son, Rupert, was born in April 1969.

Shortly afterwards, Jeremy Thorpe received a political boost when the Liberals unexpectedly won a by-election at Birmingham Ladywood, in a previously safe Labour seat.

Jeremy Thorpe barely hung on in North Devon, his majority reduced to 369.

On 14 March 1973, Jeremy Thorpe married Marion Stein, a concert pianist and the former wife of George Lascelles, 7th Earl of Harewood.

Jeremy Thorpe was confident that the party would make a significant breakthrough; on election day, 28 February, it secured its highest national vote to date, 6 million, and its highest share of the vote since 1929.

The next day, following discussions with senior colleagues, Jeremy Thorpe advised Heath that a commitment to electoral reform would be a prerequisite to any arrangement between the two parties.

Jeremy Thorpe proposed that Heath establish a Speaker's Conference whose recommendations on electoral reform would, if acceptable to the Liberals, form the basis of subsequent legislation with full cabinet approval.

Jeremy Thorpe later admitted that a coalition agreement would have torn the party apart; the more radical elements, in particular the Young Liberals, would never have accepted it.

Furthermore, Jeremy Thorpe said that "even with our support Heath wouldn't have had a parliamentary majority"; without some arrangements with the Scottish Nationalists or the Ulster Unionists, the coalition could have been brought down by the first vote on the Queen's Speech.

Jeremy Thorpe anticipated a turning point in the Liberals' fortunes and campaigned under the slogan "one more heave", aiming for a complete breakthrough with entering a coalition a last resort.

Jeremy Thorpe argued that electoral reform on a proportional basis would bring about a centrist stability to British politics that would favour British business.

The referendum resulted in a two-to-one approval of the UK's membership, but Jeremy Thorpe failed to stem the decline in his party's electoral fortunes.

The inquiry dismissed the allegations, but the danger represented by Scott continued to preoccupy Jeremy Thorpe who, according to his confidant David Holmes, felt "he would never be safe with that man around".

Scott had first met Jeremy Thorpe early in 1961 when the former was a 20-year-old groom working for one of Jeremy Thorpe's wealthy friends.

Jeremy Thorpe later acknowledged that a friendship had developed, but denied any physical relationship; Scott claimed that he had been seduced by Jeremy Thorpe on the night following the Commons meeting.

In 1965 Jeremy Thorpe asked his parliamentary colleague Peter Bessell to help him resolve the problem.

Bessell met Scott and warned him that his threats against Jeremy Thorpe might be considered blackmail; he offered to help Scott obtain a new National Insurance card, the lack of which had been a long-running source of irritation.

Bessell later stated that by 1968 Jeremy Thorpe was considering ways in which Scott might be permanently silenced; he thought David Holmes might organise this.

Jeremy Thorpe passed the information to Emlyn Hooson, who was MP for the adjoining Welsh constituency; Hooson precipitated the party inquiry which cleared Thorpe.

Jeremy Thorpe arranged for these funds to be secretly channelled to Holmes rather than the party.

Jeremy Thorpe later denied that this money had been used to pay Newton, or anyone else, as part of a conspiracy.

On 10 May 1976, amid rising criticism, Jeremy Thorpe resigned the party leadership, "convinced that a fixed determination to destroy the Leader could itself result in the destruction of the Party".

Jeremy Thorpe lobbied the government hard for legislation to introduce direct elections to the European Parliament; at that time MEPs were appointed by member nations' parliaments.

Jeremy Thorpe used his influence to insist that legislation for direct elections to the European Parliament was part of the pact, but was unable to secure his principal objective, a commitment to a proportional basis in these elections.

In parliament, Jeremy Thorpe spoke in favour of Scottish and Welsh devolution, arguing that there was no alternative to home rule except total separation.

The most persistent of these were Barry Penrose and Roger Courtiour, collectively known as "Pencourt", who had begun by believing that Jeremy Thorpe was a target of South African intelligence agencies, until their investigations led them to Bessell in California.

Bessell, no longer covering for Jeremy Thorpe, gave the reporters his version of the conspiracy to murder Scott, and Jeremy Thorpe's role in it.

Jeremy Thorpe was additionally charged with incitement to murder, on the basis of his alleged 1968 discussions with Bessell and Holmes.

Jeremy Thorpe accepted the invitation of his local party to fight the North Devon seat, against the advice of friends who were certain he would lose.

Jeremy Thorpe's campaign was largely ignored by the national party; of its leading figures only John Pardoe, the MP for North Cornwall, visited the constituency.

Jeremy Thorpe, supported by his wife, his mother and some loyal friends, fought hard, although much of his characteristic vigour was missing.

Jeremy Thorpe lost to his Conservative opponent by 8,500 votes.

Reluctantly, Jeremy Thorpe accepted that there was no future role for him within the Liberal Party, and informed the North Devon association that he would not seek to fight the seat again.

Jeremy Thorpe kept his position as chairman of the political committee of the United Nations Association, but in 1985 the progression of Parkinson's disease, which had first been diagnosed in 1979, led to the curtailment of most of his public activity.

Jeremy Thorpe thought he might return to parliament via a life peerage in the House of Lords, but although friends lobbied on his behalf, the merged party's leadership refused to recommend him.

In 1999 Jeremy Thorpe published an anecdotal memoir, In My Own Time, an anthology of his experiences in public life.

Some of Jeremy Thorpe's pro-Europeanism had been eroded over the years; in his final years, he thought that the European Union had become too powerful, and insufficiently accountable.

Jeremy Thorpe died on 6 March 2014; Thorpe survived for nine more months, dying from complications of Parkinson's disease on 4 December, aged 85.

Jeremy Thorpe positioned the Liberals in the "moderate centre", equidistant from Labour and Conservative, a strategy which was very successful in February 1974 when dissatisfaction with the two main parties was at its height, but which left the party's specific identity obscure, and its policies largely unknown.