1.

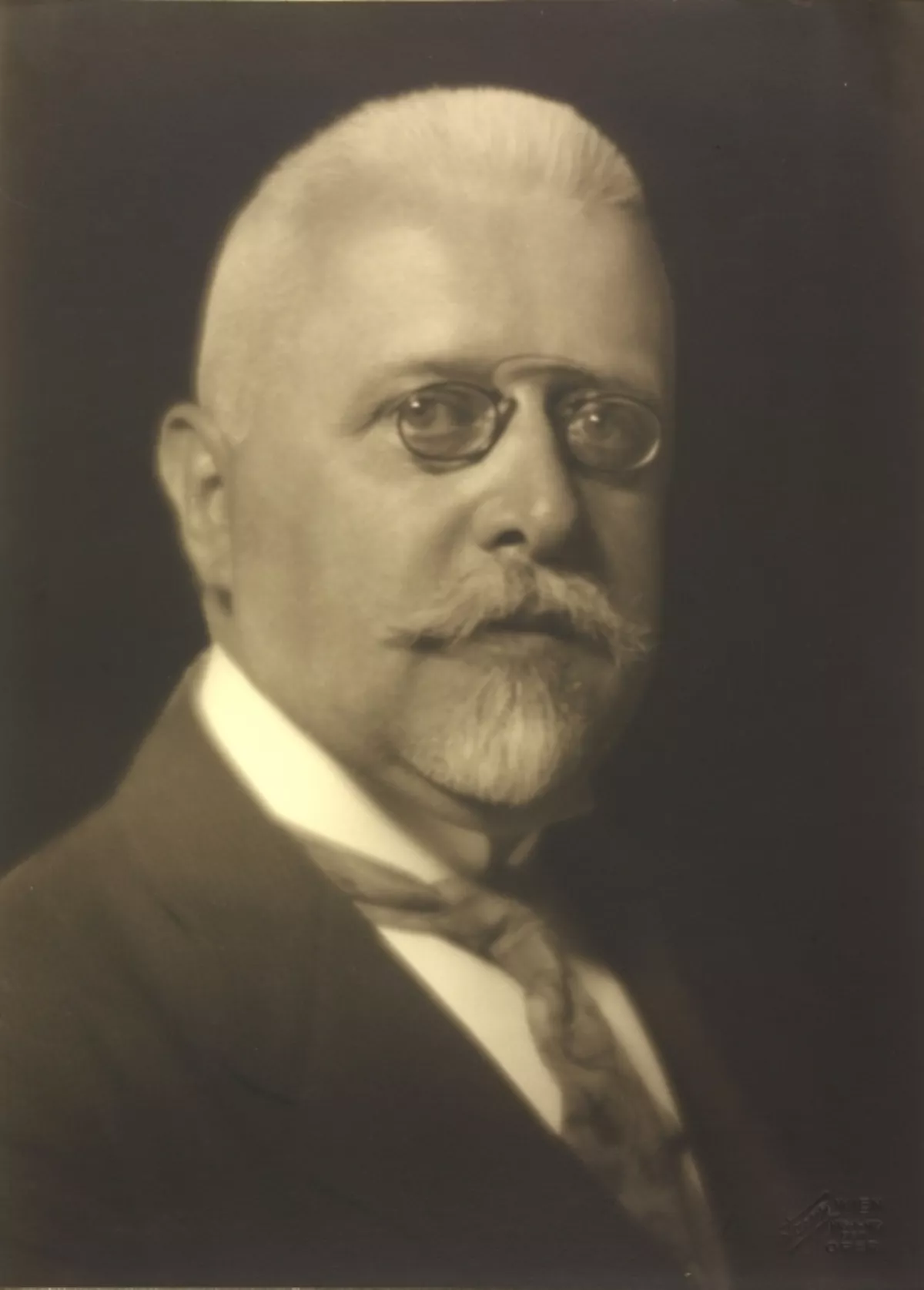

1. Johannes "Johann" Schober was an Austrian jurist, law enforcement official, and politician.

1.

1. Johannes "Johann" Schober was an Austrian jurist, law enforcement official, and politician.

Johannes Schober served as the chancellor of Austria from June 1921 to May 1922 and again from September 1929 to September 1930.

Johannes Schober served ten stints as an acting minister, variously leading the ministries of education, finance, commerce, foreign affairs, justice, and the interior, sometimes just for a few days or weeks at a time.

Johannes Schober remained the only chancellor in Austrian history with no official ideological affiliation until 2019, when Brigitte Bierlein was appointed, becoming the first woman to take office.

Johannes Schober was born on 14 November 1874 in Perg, Upper Austria.

The education they imparted on young Johannes Schober appears to have emphasized hard work, piety, and patriotism.

Johannes Schober attended the gymnasium in Linz and the Vincentinum, a Catholic boys' boarding school.

In 1894, having completed his secondary education, Johannes Schober enrolled at the University of Vienna to read law.

In 1898, Johannes Schober left the university and joined the Rudolfsheim police inspectorate as an apprentice clerk.

Johannes Schober had completed his studies but had either not taken or not passed the complete set of graduation exams.

Johannes Schober left, accordingly, not with a doctorate but an absolutorium.

In particular, it qualified Johannes Schober to receive post-graduate training for the position of lawyer in police service.

Johannes Schober had been induced to join the police by one of his favorite operas, the Evangelimann, a play based on the 1892 autobiography of a Viennese detective inspector.

On 1 March 1913, at the relatively young age of 38, Johannes Schober was made one of the heads of the Office of State Security.

When World War I broke out a little over a year later, Johannes Schober thus found himself one of the chiefs of Austrian counter-intelligence operations.

When Edmund von Gayer, the Vienna Chief of Police, was made Minister of the Interior in June 1918, Johannes Schober was appointed his successor.

Johannes Schober's crackdown earned him the trust of the political right.

Johannes Schober was known to be close to the pan-German cause but still considered nonpartisan.

Johannes Schober was respected across party divides for his competence and effectiveness.

Johannes Schober enjoyed a reputation for personal integrity, an important point in a country sick of corruption and nepotism.

All but unanimously, the new National Council invited Johannes Schober to draw up a list of ministers.

When Johannes Schober chose Josef Redlich as his Finance Minister, a post that Redlich had already held for a short while during the final days of the collapsing Empire, the Greater German People's Party vetoed Redlich on the grounds that Redlich was Jewish.

The main problems facing Johannes Schober's cabinet were Austria's galloping inflation and the country's unresolved relationship with Czechoslovakia.

Johannes Schober returned as acting minister of the interior, although not as acting minister of foreign affairs.

Johannes Schober's opponents used his absence to orchestrate his replacement.

Johannes Schober undertook to modernize the force, to expand its capacities, and to intensify international cooperation.

In 1923, Johannes Schober convened an International Police Congress and took the initiative in creating Interpol.

Johannes Schober personally assumed the role of Interpol's founding president.

Johannes Schober otherwise focused on centralizing the Austrian police corps' command structure and on strengthening traffic police, criminal police, the intelligence network, and the force's internal welfare program.

Johannes Schober worked to reduce to influence of Social Democrats on the force.

Johannes Schober became a deeply controversial figure for the rest of his life and for decades beyond.

Johannes Schober launched a poster campaign and railed against Schober in a 1928 stage play, The Insurmountables.

Johannes Schober was elated when Karl Seitz, a leading Social Democrat and the Mayor of Vienna, extended a personal apology in 1929.

Johannes Schober himself became acting minister again, this time leading the ministries of education and of finance.

Johannes Schober invited Social Democratic representatives to join the talks and refused to be intimidated by the rallies the Heimwehr kept staging as a show of force.

In particular, Johannes Schober convinced the Allies of World War I, on a conference in The Hague in January 1930, to forgive the reparations that Austria still owed.

Observers noted that Johannes Schober achieved his diplomatic victories through a strategy of comporting himself as an affable simpleton.

Short, pudgy, intellectually outmatched, eager to oblige, happy to be patronized, and head of a country that was no threat to anyone any more, Johannes Schober seems to have put his negotiating partners into a generous mood.

Vaugoin, a friend of the Heimwehr to begin with, provoked a quarrel with Johannes Schober by demanding that Franz Strafella be appointed director general of the Austrian Railways; Strafella was both a noted Heimwehr man and known to be corrupt.

Johannes Schober installed Vaugoin as Schober's successor and Seipel as his minister of foreign affairs.

The Heimwehr, made confident by its easy victory over Johannes Schober and intrigued by the successes of the Nazi Party in Germany, now decided to break with the Christian Socials and stand for election as a separate party, the Homeland Bloc.

People's Party and Landbund united against their common enemy and convinced Johannes Schober to serve as the leader of their alliance, which they proceeded to name the Johannes Schober Bloc.

Johannes Schober stayed on, serving in the first Buresch government both as the vice chancellor and as the acting minister of foreign affairs.

Johannes Schober had been suffering from heart disease; his condition had noticeably worsened during his final months.

Johannes Schober's death came a mere three weeks after the death of Ignaz Seipel, who had been struggling with long illness.