1.

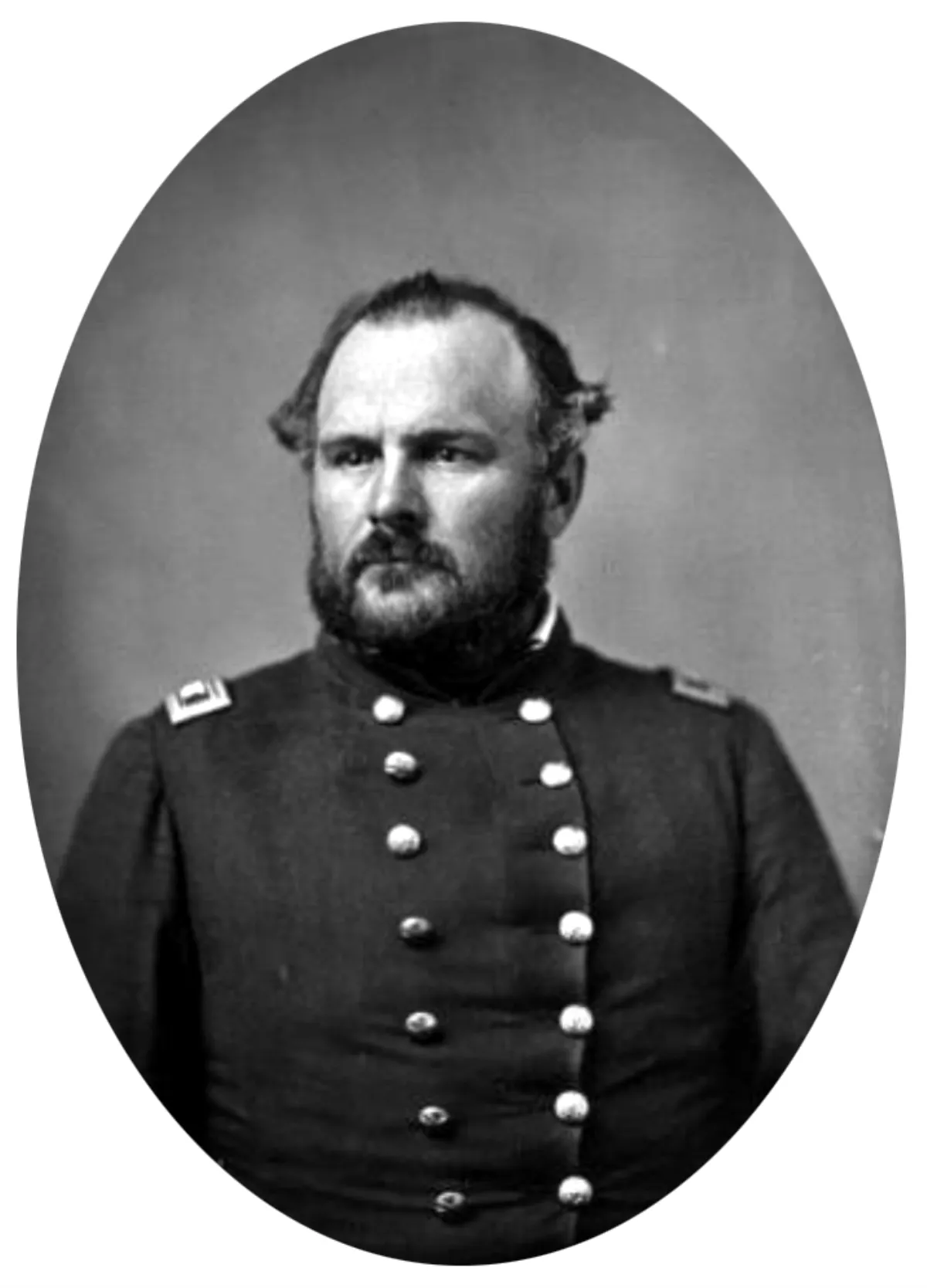

1. John Milton Chivington was a Methodist pastor and Mason who served as a colonel in the United States Volunteers during the New Mexico Campaign of the American Civil War.

1.

1. John Milton Chivington was a Methodist pastor and Mason who served as a colonel in the United States Volunteers during the New Mexico Campaign of the American Civil War.

John Chivington led a rear action against a Confederate supply train in the Battle of Glorieta Pass that had the effect of ending the Confederacy's campaigns in the Western states, and was then appointed a colonel of cavalry during the Colorado War.

Colonel Chivington gained infamy for leading the 700-man force of Colorado Territory volunteers responsible for one of the most heinous atrocities in American military history: the November 1864 Sand Creek massacre.

John Chivington and his men took scalps and many other human body parts as trophies, including unborn fetuses, as well as male and female genitalia.

John Chivington suffered was public exposure and the end of his political aspirations.

John Chivington was born in Lebanon, Ohio on January 27,1821, the son of Isaac and Jane John Chivington, who had fought under General William Henry Harrison against members of Tecumseh's Confederacy at the Battle of the Thames.

In May 1860, John Chivington moved, with his family, to the Colorado Territory and settled in Denver.

John Chivington was elected Presiding Elder of the new Rocky Mountain District and served in that capacity until 1862.

Historian of Methodism Isaac Beardsley, a personal friend of John Chivington, suggested that John Chivington was "thrown out" because of his involvement with the armed forces.

John Chivington's name appears as a member of the executive board of Colorado Seminary, the historic precursor of the University of Denver and the Iliff School of Theology.

John Chivington's name appears in the incorporation document issued by the Council and House of Representatives of the Colorado Territory, which was approved by then governor John Evans.

John Chivington was commissioned a major in the 1st Colorado Infantry Regiment under Colonel John P Slough.

The startled Texans were routed with four killed, 20 wounded and 75 captured, while John Chivington's men lost five killed and 14 wounded.

John Chivington got into position above the Pass, but waited in vain for either Slough or Sibley to arrive.

John Chivington's command, among whom there was a detail of Colorado Mounted Rangers, descended the slope and crept up on the supply train.

John Chivington ordered the supply wagons burned, and the horses and mules slaughtered.

John Chivington returned to Slough's main force to find it rapidly falling back.

Critics have suggested that had John Chivington returned quickly to reinforce Slough's army when he heard gunfire, his 400 extra men might have allowed the Union to win the battle.

In November, John Chivington was appointed brigadier general of volunteers, an appointment withdrawn in February 1863.

John Chivington's superiors expressed enough concern that he was putting his political interests ahead of his duties that he had to write Major General Samuel Ryan Curtis, commander of the Department of Kansas, a letter of reassurance.

The latter was granted, and John Chivington formed the 3rd Colorado Cavalry Regiment from a group of volunteers who largely lacked combat experience, to protect Denver and the Platte road.

For political reasons, Evans had stoked the fears of the populace regarding Indian attacks, and he and John Chivington both hoped successful military engagements against the Indians would further their careers.

Wynkoop convinced a reluctant Evans, along with John Chivington, to meet with the chiefs.

Tensions had eased even before the Camp Weld conference, meaning the battle John Chivington had hoped for less likely.

Joe Cramer said that with the Indians currently showing no signs of preparing for war, John Chivington's plans amounted to mass murder.

John Chivington threatened to hang Soule for attempting to incite mutiny and told the others who had challenged his orders that they should leave the Army.

John Chivington testified before a Congressional committee that his forces had killed 500 to 600 Indians and that few of them were women or children.

However, the testimony of Soule, Cramer and his men contradicted their commander and resulted in a US Congressional investigation into the incident, which concluded that John Chivington had acted wrongly.

John Chivington was condemned for his part in the massacre, but he had already resigned from the Army in June or July of 1865.

In 1865 his son, Thomas, drowned and John Chivington returned to Nebraska to administer the estate.

Public outrage forced John Chivington to withdraw from politics and kept him out of Colorado's campaign for statehood.

In July 1868, John Chivington went to Washington, DC in an unsuccessful pursuit of a $37,000 claim for Indian depredations.

John Chivington returned to Omaha, but journeyed to Troy, New York, during 1869 to stay with Sarah's relatives.

John Chivington borrowed money from them but did not repay.

John Chivington returned to Denver where he worked as a deputy sheriff until shortly before his death from cancer in 1894.

John Chivington's funeral took place at the city's Trinity United Methodist Church before his remains were interred at Fairmount Cemetery.

John Chivington argued that his expedition was a response to Cheyenne and Arapaho raids and torture inflicted on wagon trains and white settlements in Colorado.

John Chivington violated official agreements for protection of Black Kettle's friendly band.

John Chivington overlooked how the massacre caused the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux to strengthen their alliance and to accelerate their raids on white settlers.

In 2005, the City Council of Longmont, Colorado, agreed to change the name of John Chivington Drive in the town following a two-decade campaign.

Protesters had objected to John Chivington being honored for the Sand Creek Massacre.