1.

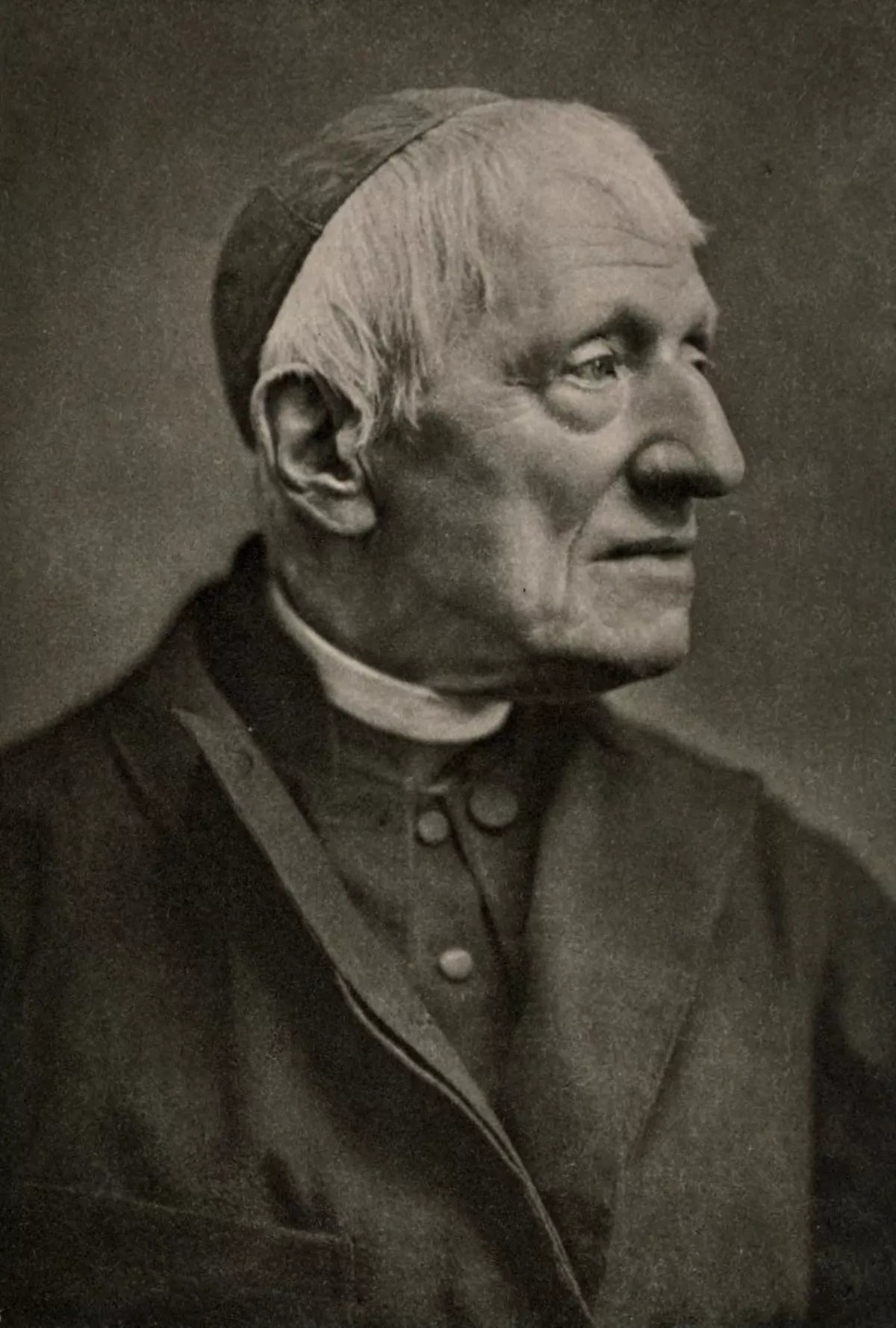

1. John Henry Newman was an English Catholic theologian, academic, philosopher, historian, writer, and poet.

1.

1. John Henry Newman was an English Catholic theologian, academic, philosopher, historian, writer, and poet.

John Henry Newman was previously an Anglican priest and after his conversion became a cardinal.

John Henry Newman was an important and controversial figure in the religious history of England in the 19th century and was known nationally by the mid-1830s.

John Henry Newman was canonised as a Catholic saint in 2019.

John Henry Newman was a member of the Oratory of St Philip Neri.

Originally an evangelical academic at the University of Oxford and priest in the Church of England, Newman was drawn to the high church tradition of Anglicanism.

John Henry Newman became one of the more notable leaders of the Oxford Movement, an influential and controversial grouping of Anglicans who wished to restore to the Church of England many Catholic beliefs and liturgical rituals from before the English Reformation.

In 1845, John Henry Newman resigned his teaching post at Oxford University, and, joined by some but not all of his followers, officially left the Church of England and was received into the Catholic Church.

John Henry Newman was quickly ordained as a priest and continued as an influential religious leader, based in Birmingham.

John Henry Newman was instrumental in the founding of the Catholic University of Ireland in 1854, which later became University College Dublin.

John Henry Newman was a literary figure: his major writings include the Tracts for the Times, his autobiography Apologia Pro Vita Sua, the Grammar of Assent, and the poem The Dream of Gerontius, which was set to music in 1900 by Edward Elgar.

John Henry Newman's beatification was proclaimed by Pope Benedict XVI on 19 September 2010 during his visit to the United Kingdom.

John Henry Newman's canonisation was officially approved by Pope Francis on 12 February 2019, and took place on 13 October 2019.

John Henry Newman was born on 21 February 1801 in the City of London, the eldest of a family of three sons and three daughters.

John Henry Newman's father, John Newman, was a banker with Ramsbottom, Newman and Company in Lombard Street.

At the age of seven John Henry Newman was sent to Great Ealing School conducted by George Nicholas.

John Henry Newman was a great reader of the novels of Walter Scott, then in course of publication, and of Robert Southey.

At the age of 15, during his last year at school, John Henry Newman converted to Evangelical Christianity, an incident of which he wrote in his Apologia that it was "more certain than that I have hands or feet".

John Henry Newman read The Force of Truth by Thomas Scott.

John Henry Newman was sent shortly to Trinity College, Oxford, where he studied widely.

John Henry Newman was elected a fellow at Oriel on 12 April 1822.

On 13 June 1824, John Henry Newman was made an Anglican deacon at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford.

John Henry Newman became, at Pusey's suggestion, curate of St Clement's Church, Oxford.

In 1825, at Whately's request, John Henry Newman became vice-principal of St Alban Hall, but he held this post for only one year.

John Henry Newman attributed much of his "mental improvement" and partial conquest of his shyness at this time to Whately.

In 1826 John Henry Newman returned as a tutor to Oriel, and the same year Richard Hurrell Froude, described by John Henry Newman as "one of the acutest, cleverest and deepest men" he ever met, was elected fellow there.

John Henry Newman assisted Whately in his popular work Elements of Logic, and from him gained a definite idea of the Christian Church as institution: "a Divine appointment, and as a substantive body, independent of the State, and endowed with rights, prerogatives and powers of its own".

John Henry Newman broke with Whately in 1827 on the occasion of the re-election of Robert Peel as Member of Parliament for the university: John Henry Newman opposed Peel on personal grounds.

At this date, though John Henry Newman was still nominally associated with the Evangelicals, his views were gradually assuming a higher ecclesiastical tone.

In December 1832, John Henry Newman accompanied Archdeacon Robert Froude and his son Hurrell on a tour in southern Europe on account of the latter's health.

On board the mail steamship Hermes they visited Gibraltar, Malta, the Ionian Islands and, subsequently, Sicily, Naples and Rome, where John Henry Newman made the acquaintance of Nicholas Wiseman.

John Henry Newman fell dangerously ill with gastric or typhoid fever at Leonforte, but recovered, with the conviction that God still had work for him to do in England.

John Henry Newman was at home again in Oxford on 9 July 1833 and, on 14 July, Keble preached at St Mary's an assize sermon on "National Apostasy", which John Henry Newman afterwards regarded as the inauguration of the Oxford Movement.

At this date, John Henry Newman became editor of the British Critic.

John Henry Newman gave courses of lectures in a side chapel of St Mary's in defence of the via media of Anglicanism between Roman Catholicism and popular Protestantism.

Since accepting his post at St Mary's, John Henry Newman had a chapel and a school built in the parish's neglected area.

John Henry Newman planned to appoint Charles Pourtales Golightly, an Oriel man, as curate at Littlemore in 1836.

Isaac Williams became Littlemore's curate instead, succeeded by John Henry Newman Rouse Bloxam from 1837 to 1840, during which the school opened.

John Henry Newman continued as a High Anglican controversialist until 1841, when he published Tract 90, which proved the last of the series.

John Henry Newman resigned the editorship of the British Critic and was thenceforth, as he later described it, "on his deathbed as regards membership with the Anglican Church".

John Henry Newman now considered the position of Anglicans to be similar to that of the semi-Arians in the Arian controversy.

In 1842 John Henry Newman withdrew to Littlemore with a small band of followers, and lived in semi-monastic conditions.

John Henry Newman called it "the house of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Littlemore".

Some John Henry Newman disciples wrote about English saints, while John Henry Newman himself worked to complete an Essay on the development of doctrine.

In February 1843, John Henry Newman published, as an advertisement in the Oxford Conservative Journal, an anonymous but otherwise formal retractation of all the hard things he had said against Roman Catholicism.

An interval of two years then elapsed before John Henry Newman was received into the Catholic Church on 9 October 1845 by Dominic Barberi, an Italian Passionist, at the college in Littlemore.

The effect on the wider Tractarian movement is still debated since John Henry Newman's leading role is regarded by some scholars as overstated, as is Oxford's domination of the movement as a whole.

In February 1846, John Henry Newman left Oxford for St Mary's College, Oscott, where Nicholas Wiseman, then vicar-apostolic of the Midland district, resided; and in October he went to Rome, where he was ordained priest by Cardinal Giacomo Filippo Fransoni and awarded the degree of Doctor of Divinity by Pope Pius IX.

At the close of 1847, John Henry Newman returned to England as an Oratorian and resided first at Maryvale ; then at St Wilfrid's College, Cheadle; and then at St Anne's, Alcester Street, Birmingham.

The prime minister, John Henry Newman Russell, wrote a public letter to the Bishop of Durham and denounced this "attempt to impose a foreign yoke upon our minds and consciences".

John Henry Newman was keen for lay people to be at the forefront of any public apologetics, writing that Catholics should "make the excuse of this persecution for getting up a great organization, going round the towns giving lectures, or making speeches".

John Henry Newman supported John Capes in the committee he was organising for public lectures in February 1851.

John Henry Newman took the initiative and booked the Birmingham Corn Exchange for a series of public lectures.

John Henry Newman decided to make their tone popular and provide cheap off-prints to those who attended.

Gillow accused John Henry Newman of giving the impression that the church's infallibility resides in a partnership between the hierarchy and the faithful, rather than falling exclusively in the teaching office of the church, a concept described by Pope Pius IX as the "ordinary magisterium" of the church.

Archdeacon Julius Hare said that John Henry Newman "is determined to say whatever he chooses, in spite of facts and reason".

Ker notes that John Henry Newman's imagery has a "savage, Swiftian flavour" and can be "grotesque in the Dickens manner".

John Henry Newman therefore assumed, after seeking legal advice, that he would be able to repeat the facts in his fifth lecture in his Lectures on the Present Position of Catholics in England.

Under English law, John Henry Newman needed to prove every single charge he had made against Achilli.

John Henry Newman requested the documents that Wiseman had used for his article in the Dublin Review but he had mislaid them.

John Henry Newman eventually found them but it was too late to prevent the trial.

John Henry Newman removed the libellous section of the fifth lecture and replaced it with the inscription:.

In 1854, at the request of the Irish Catholic bishops, John Henry Newman went to Dublin as rector of the newly established Catholic University of Ireland, now University College Dublin.

John Henry Newman published a volume of lectures entitled The Idea of a University, which explained his philosophy of education.

John Henry Newman's purpose was to build a Catholic university, in a world where the major Catholic universities on the European continent had recently been secularised, and most universities in the English-speaking world were Protestant.

The university as envisaged by John Henry Newman encountered too much opposition to prosper.

In 1858, Newman projected a branch house of the Oratory at Oxford; but this project was opposed by Father Henry Edward Manning, another influential convert from Anglicanism, and others.

In 1859, John Henry Newman established, in connection with the Birmingham Oratory, a school for the education of the sons of gentlemen along lines similar to those of English public schools.

John Henry Newman published several books with the company, effectively saving it.

Newman and Henry Edward Manning both became significant figures in the late 19th-century Catholic Church in England: both were Anglican converts and both were elevated to the dignity of cardinal.

When John Henry Newman died there appeared in a monthly magazine a series of very unflattering sketches by one who had lived under his roof.

In 1862 John Henry Newman began to prepare autobiographical and other memoranda to vindicate his career.

Father John Henry Newman informs us that it need not, and on the whole ought not to be.

John Henry Newman maintains that English Catholic priests are at least as truthful as English Catholic laymen.

John Henry Newman published a revision of the series of pamphlets in book form in 1865; in 1913 a combined critical edition, edited by Wilfrid Ward, was published.

In 1870, John Henry Newman published his Grammar of Assent, a closely reasoned work in which the case for religious belief is maintained by arguments somewhat different from those commonly used by Catholic theologians of the time.

At the time of the First Vatican Council, John Henry Newman was uneasy about the formal definition of the doctrine of papal infallibility, believing that the time was "inopportune".

John Henry Newman gave no sign of disapproval when the doctrine was finally defined, but was an advocate of the "principle of minimising", that included very few papal declarations within the scope of infallibility.

Subsequently, in a letter nominally addressed to the Duke of Norfolk when Gladstone accused the Roman church of having "equally repudiated modern thought and ancient history", John Henry Newman affirmed that he had always believed in the doctrine, and had only feared the deterrent effect of its definition on conversions on account of acknowledged historical difficulties.

Cardinal Manning seems not to have been interested in having John Henry Newman become a cardinal and remained silent when the Pope asked him about it.

John Henry Newman accepted the gesture as a vindication of his work, but made two requests: that he not be consecrated a bishop on receiving the cardinalate, as was usual at that time; and that he might remain in Birmingham.

John Henry Newman was elevated to the rank of cardinal in the consistory of 12 May 1879 by Pope Leo XIII, who assigned him the Deaconry of San Giorgio al Velabro.

In 1880, John Henry Newman confessed to an "extreme joy" that Conservative Benjamin Disraeli was no longer in power, and expressed the hope that Disraeli would be gone permanently.

John Henry Newman celebrated Mass for the last time on Christmas Day in 1889.

The pall over the coffin bore the motto that John Henry Newman adopted for use as a cardinal, Cor ad cor loquitur, which William Barry, writing in the Catholic Encyclopedia, traces to Francis de Sales and sees as revealing the secret of John Henry Newman's "eloquence, unaffected, graceful, tender, and penetrating".

Ambrose St John had become a Roman Catholic at around the same time as Newman, and the two men have a joint memorial stone inscribed with the motto Newman had chosen, Ex umbris et imaginibus in veritatem, which Barry traces to Plato's allegory of the cave.

John Henry Newman's grave was opened on 2 October 2008, with the intention of moving any remains to a tomb inside Birmingham Oratory for their more convenient veneration as relics during John Henry Newman's consideration for sainthood; however, his wooden coffin was found to have disintegrated and no bones were found.

John Henry Newman said that extreme conditions which could remove bone would have removed the coffin handles, which were extant.

James Joyce had a lifelong admiration for John Henry Newman's writing style and in a letter to his patron Harriet Shaw Weaver remarked about John Henry Newman that "nobody has ever written English prose that can be compared with that of a tiresome footling little Anglican parson who afterwards became a prince of the only true church".

John Henry Newman defined theology as "the Science of God, or the truths we know about God, put into a system, just as we have a science of the stars and call it astronomy, or of the crust of the earth and call it geology".

Around 1830, John Henry Newman developed a distinction between natural religion and revealed religion.

For John Henry Newman, this knowledge of God is not the result of unaided reason but of reason aided by grace, and so he speaks of natural religion as containing a revelation, even though it is an incomplete revelation.

John Henry Newman held that "freedom from symbols and articles is abstractedly the highest state of Christian communion", but was "the peculiar privilege of the primitive Church".

John Henry Newman was worried about the new dogma of papal infallibility advocated by an "aggressive and insolent faction", fearing that the definition might be expressed in over-broad terms open to misunderstanding and would pit religious authority against physical science.

John Henry Newman lived in the world of his time, travelling by train as soon as engines were built and rail lines laid, and writing amusing letters about his adventures on railways and ships, and during his travels in Scotland and Ireland.

John Henry Newman was an indefatigable walker, and as a young don at Oriel he often went out riding with Hurrell Froude and other friends.

John Henry Newman was a caring pastor, and their recorded reminiscences show that they held him in affection.

John Henry Newman, who was only a few years younger than Keats and Shelley, was born into the Romantic generation when Englishmen still wept in moments of emotion.

Strachey was only ten when John Henry Newman died and never met him.

John Henry Newman was a noted beauty, who at age fifty was described by one admirer as "the handsomest woman I ever saw in my life".

John Henry Newman had a photographic portrait of her in his room and was still corresponding with her into their eighties.

For John Henry Newman, friendship is an intimation of a greater love, a foretaste of heaven.

John Henry Newman expressed his hope, Newman wrote, that during his whole priestly life he had not committed one mortal sin.

Newman's burial with St John was not unusual at the time and did not draw contemporary comment.

When Ian Ker reissued his biography of John Henry Newman in 2009, he added an afterword in which he put forward evidence that John Henry Newman was a heterosexual.

John Henry Newman cited journal entries from December 1816 in which the 15-year-old Newman prayed to be preserved from the temptations awaiting him when he returned from boarding school and met girls at Christmas dances and parties.

John Henry Newman founded the independent school for boys Catholic University School, Dublin, and the Catholic University of Ireland which evolved into University College Dublin, a college of Ireland's largest university, the National University of Ireland.

The approval of a further miracle at the intercession of John Henry Newman was reported in November 2018: the healing of a pregnant woman from a grave illness.

On 1 July 2019, with an affirmative vote, John Henry Newman's canonisation was authorised and the date for the canonisation ceremony was set for 13 October 2019.

John Henry Newman was canonised on 13 October 2019, by Pope Francis, in St Peter's Square.