1.

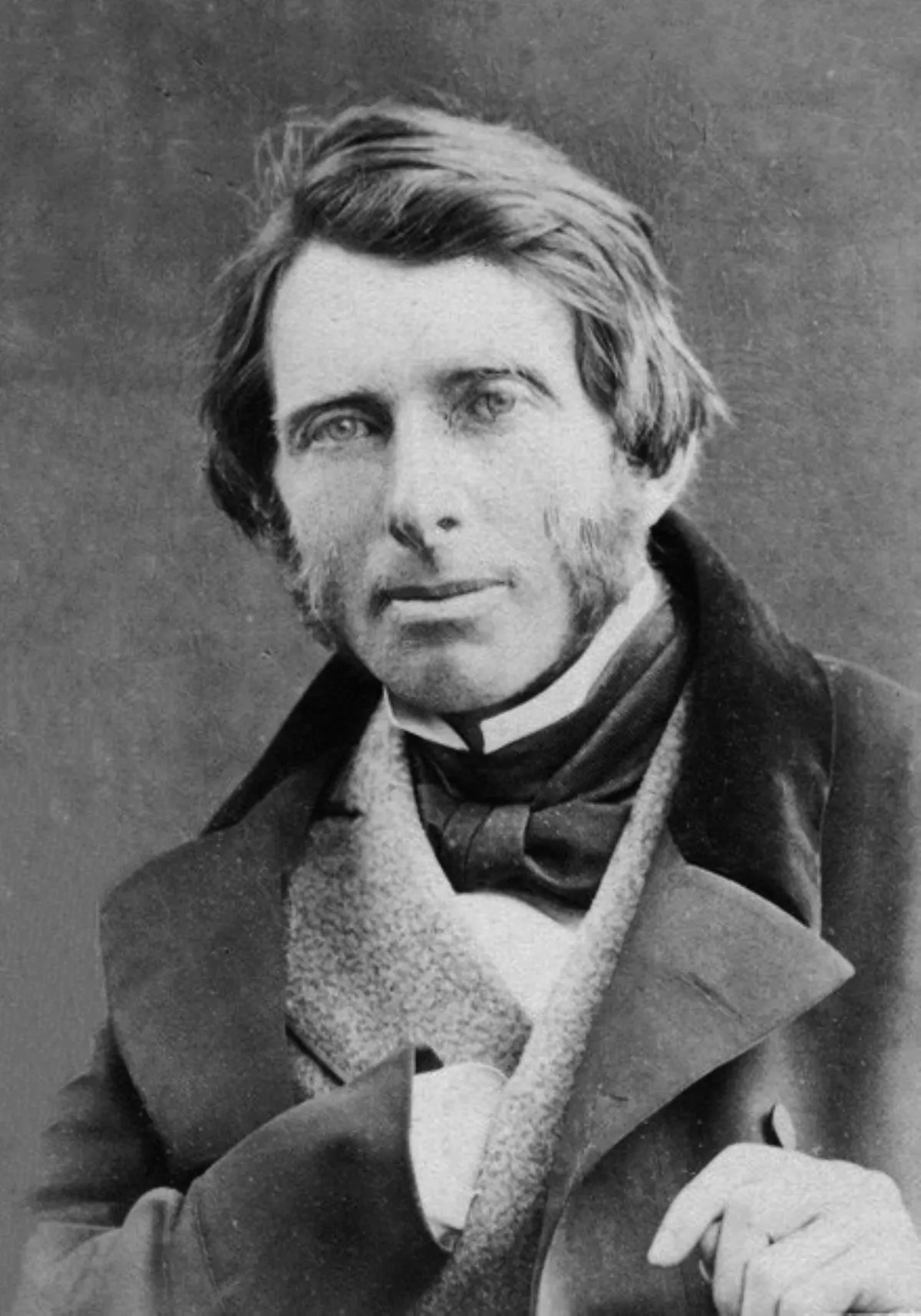

1. John Ruskin wrote on subjects as varied as art, architecture, political economy, education, museology, geology, botany, ornithology, literature, history, and myth.

1.

1. John Ruskin wrote on subjects as varied as art, architecture, political economy, education, museology, geology, botany, ornithology, literature, history, and myth.

John Ruskin wrote essays and treatises, poetry and lectures, travel guides and manuals, letters and even a fairy tale.

John Ruskin made detailed sketches and paintings of rocks, plants, birds, landscapes, architectural structures and ornamentation.

In 1869, John Ruskin became the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at the University of Oxford, where he established the John Ruskin School of Drawing.

John Ruskin's father, John James Ruskin, was a sherry and wine importer, founding partner and de facto business manager of Ruskin, Telford and Domecq.

John Ruskin James was born and brought up in Edinburgh, Scotland, to a mother from Glenluce and a father originally from Hertfordshire.

John Ruskin had joined the Ruskin household when she became companion to John James's mother, Catherine.

John Ruskin James had hoped to practise law, and was articled as a clerk in London.

John Ruskin's father, John Thomas Ruskin, described as a grocer, was an incompetent businessman.

John Ruskin James died on 3 March 1864 and is buried in the churchyard of St John Ruskin the Evangelist, Shirley, Croydon.

John Ruskin was born on 8 February 1819 at 54 Hunter Street, Brunswick Square, London, south of what is St Pancras railway station.

John Ruskin's childhood was shaped by the contrasting influences of his father and mother, both of whom were fiercely ambitious for him.

Margaret Ruskin, an evangelical Christian, more cautious and restrained than her husband, taught young John to read the Bible from beginning to end, and then to start all over again, committing large portions to memory.

John Ruskin read alternate verses with me, watching at first, every intonation of my voice, and correcting the false ones, till she made me understand the verse, if within my reach, rightly and energetically.

John Ruskin had few friends of his own age, but it was not the friendless and joyless experience he later said it was in his autobiography, Praeterita.

John Ruskin heard Dale lecture in 1836 at King's College, London, where Dale was the first Professor of English Literature.

John Ruskin went on to enrol and complete his studies at King's College, where he prepared for Oxford under Dale's tutelage.

John Ruskin was greatly influenced by the extensive and privileged travels he enjoyed in his childhood.

John Ruskin sometimes accompanied his father on visits to business clients at their country houses, which exposed him to English landscapes, architecture and paintings.

John Ruskin developed a lifelong love of the Alps, and in 1835 visited Venice for the first time, that 'Paradise of cities' that provided the subject and symbolism of much of his later work.

John Ruskin composed elegant, though mainly conventional poetry, some of which was published in Friendship's Offering.

In Michaelmas 1836, John Ruskin matriculated at the University of Oxford, taking up residence at Christ Church in January of the following year.

John Ruskin was generally uninspired by Oxford and suffered bouts of illness.

John Ruskin became close to the geologist and natural theologian William Buckland.

John Ruskin met William Wordsworth, who was receiving an honorary degree, at the ceremony.

John Ruskin's health was poor and he never became independent from his family during his time at Oxford.

John Ruskin's mother took lodgings on High Street, where his father joined them at weekends.

John Ruskin was devastated to hear that his first love, Adele Domecq, the second daughter of his father's business partner, had become engaged to a French nobleman.

Back at Oxford, in 1842 John Ruskin sat for a pass degree, and was awarded an uncommon honorary double fourth-class degree in recognition of his achievements.

For much of the period from late 1840 to autumn 1842, John Ruskin was abroad with his parents, mainly in Italy.

John Ruskin James had sent the piece to Turner, who did not wish it to be published.

John Ruskin maintained that, unlike Turner, Old Masters such as Gaspard Dughet, Claude, and Salvator Rosa favoured pictorial convention, and not "truth to nature".

John Ruskin explained that he meant "moral as well as material truth".

John Ruskin described works he had seen at the National Gallery and Dulwich Picture Gallery with extraordinary verbal felicity.

Suddenly John Ruskin had found his metier, and in one leap helped redefine the genre of art criticism, mixing a discourse of polemic with aesthetics, scientific observation and ethics.

John Ruskin toured the continent with his parents again during 1844, visiting Chamonix and Paris, studying the geology of the Alps and the paintings of Titian, Veronese and Perugino among others at the Louvre.

In Lucca he saw the Tomb of Ilaria del Carretto by Jacopo della Quercia, which John Ruskin considered the exemplar of Christian sculpture.

John Ruskin drew inspiration from what he saw at the Campo Santo in Pisa, and in Florence.

John Ruskin explicitly linked the aesthetic and the divine, arguing that truth, beauty and religion are inextricably bound together: "the Beautiful as a gift of God".

In defining categories of beauty and imagination, John Ruskin argued that all great artists must perceive beauty and, with their imagination, communicate it creatively by means of symbolic representation.

The European Revolutions of 1848 meant that the newlyweds' earliest travels together were restricted, but they were able to visit Normandy, where John Ruskin admired the Gothic architecture.

Effie was too unwell to undertake the European tour of 1849, so John Ruskin visited the Alps with his parents, gathering material for the third and fourth volumes of Modern Painters.

John Ruskin was struck by the contrast between the Alpine beauty and the poverty of Alpine peasants, stirring his increasingly sensitive social conscience.

The marriage was unhappy, with John Ruskin reportedly being cruel to Effie and distrustful of her.

John Ruskin's developing interest in architecture, and particularly in the Gothic, led to the first work to bear his name, The Seven Lamps of Architecture.

The title refers to seven moral categories that John Ruskin considered vital to and inseparable from all architecture: sacrifice, truth, power, beauty, life, memory and obedience.

For Effie, Venice provided an opportunity to socialise, while John Ruskin was engaged in solitary studies.

Meanwhile, John Ruskin was making the extensive sketches and notes that he used for his three-volume work The Stones of Venice.

John Ruskin became acquainted with Millais after the artists made an approach to John Ruskin through their mutual friend Coventry Patmore.

The John Ruskin marriage was already undermined as she and Millais fell in love, and Effie left John Ruskin, causing a public scandal.

The complex reasons for the non-consummation and ultimate failure of the John Ruskin marriage are a matter of enduring speculation and debate.

John Ruskin's father's disapproval of such friends was a further cause of tension between them.

John Ruskin created many careful studies of natural forms, based on his detailed botanical, geological and architectural observations.

John Ruskin's theories inspired some architects to adapt the Gothic style.

John Ruskin had taught several women drawing, by means of correspondence, and his book represented both a response and a challenge to contemporary drawing manuals.

From 1859 until 1868, John Ruskin was involved with the progressive school for girls at Winnington Hall in Cheshire.

In MP III John Ruskin argued that all great art is "the expression of the spirits of great men".

John Ruskin gave the inaugural address at the Cambridge School of Art in 1858, an institution from which the modern-day Anglia John Ruskin University has grown.

John Ruskin had been in Venice when he heard about Turner's death in 1851.

John Ruskin persuaded the National Gallery to allow him to work on the Turner Bequest of nearly 20,000 individual artworks left to the nation by the artist.

Recent scholarship has argued that John Ruskin did not, as previously thought, collude in the destruction of Turner's erotic drawings, but his work on the Bequest did modify his attitude towards Turner.

John Ruskin's confidence undermined, he believed that much of his writing to date had been founded on a bed of lies and half-truths.

John Ruskin continued to draw and paint in watercolours, and to travel extensively across Europe with servants and friends.

Yet increasingly John Ruskin concentrated his energies on fiercely attacking industrial capitalism, and the utilitarian theories of political economy underpinning it.

John Ruskin repudiated his sometimes grandiloquent style, writing now in plainer, simpler language, to communicate his message straightforwardly.

John Ruskin articulated an extended metaphor of household and family, drawing on Plato and Xenophon to demonstrate the communal and sometimes sacrificial nature of true economics.

John Ruskin's ideas influenced the concept of the "social economy", characterised by networks of charitable, co-operative and other non-governmental organisations.

The reaction of the national press was hostile, and John Ruskin was, he claimed, "reprobated in a violent manner".

John Ruskin asserted that the components of the greatest artworks are held together, like human communities, in a quasi-organic unity.

John Ruskin further explored political themes in Time and Tide, his letters to Thomas Dixon, a cork-cutter in Sunderland, Tyne and Wear who had a well-established interest in literary and artistic matters.

John Ruskin lectured widely in the 1860s, giving the Rede lecture at the University of Cambridge in 1867, for example.

John Ruskin was unanimously appointed the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford University in August 1869, though largely through the offices of his friend, Henry Acland.

John Ruskin delivered his inaugural lecture on his 51st birthday in 1870, at the Sheldonian Theatre to a larger-than-expected audience.

In 1871, John Ruskin founded his own art school at Oxford, The Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art.

John Ruskin established a large collection of drawings, watercolours and other materials that he used to illustrate his lectures.

John Ruskin lectured on a wide range of subjects at Oxford, his interpretation of "Art" encompassing almost every conceivable area of study, including wood and metal engraving, the relation of science to art and sculpture.

John Ruskin's lectures ranged through myth, ornithology, geology, nature-study and literature.

In 1879, John Ruskin resigned from Oxford, but resumed his Professorship in 1883, only to resign again in 1884.

John Ruskin gave his reason as opposition to vivisection, but he had increasingly been in conflict with the University authorities, who refused to expand his Drawing School.

In January 1871, the month before John Ruskin started to lecture the wealthy undergraduates at Oxford University, he began his series of 96 "letters to the workmen and labourers of Great Britain" under the title Fors Clavigera.

From 1873, John Ruskin had full control over all his publications, having established George Allen as his sole publisher.

John Ruskin found particular fault with Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, and accused Whistler of asking two hundred guineas for "flinging a pot of paint in the public's face".

Whistler filed a libel suit against Ruskin, but Ruskin was ill when the case went to trial in November 1878, so the artist Edward Burne-Jones and Attorney General Sir John Holker represented him.

Edward Burne-Jones, representing John Ruskin, asserted that Nocturne in Black and Gold was not a serious work of art.

John Ruskin's were paid by public subscription organised by the Fine Art Society, but Whistler was bankrupt within six months, and was forced to sell his house on Tite Street in London and move to Venice.

John Ruskin founded his utopian society, the Guild of St George, in 1871.

John Ruskin wished to show that contemporary life could still be enjoyed in the countryside, with land being farmed by traditional means, in harmony with the environment, and with the minimum of mechanical assistance.

John Ruskin sought to educate and enrich the lives of industrial workers by inspiring them with beautiful objects.

John Ruskin purchased land initially in Totley, near Sheffield, but the agricultural scheme established there by local communists met with only modest success after many difficulties.

In principle, John Ruskin worked out a scheme for different grades of "Companion", wrote codes of practice, described styles of dress and even designed the Guild's own coins.

John Ruskin wished to see St George's Schools established, and published various volumes to aid its teaching, but the schools themselves were never established.

Maria La Touche, a minor Irish poet and novelist, asked John Ruskin to teach her daughters drawing and painting in 1858.

John Ruskin's first meeting came at a time when Ruskin's own religious faith was under strain.

John Ruskin's increasing need to believe in a meaningful universe and a life after death, both for himself and his loved ones, helped to revive his Christian faith in the 1870s.

John Ruskin continued to travel, studying the landscapes, buildings and art of Europe.

In 1874, on his tour of Italy, John Ruskin visited Sicily, the furthest he ever travelled.

John Ruskin wrote about Scott, Byron and Wordsworth in Fiction, Fair and Foul in which, as Seth Reno argues, he describes the devastating effects on the landscape caused by industrialization, a vision Reno sees as a realization of the Anthropocene.

John Ruskin returned to meteorological observations in his lectures, The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth-Century, describing the apparent effects of industrialisation on weather patterns.

John Ruskin's Storm-Cloud has been seen as foreshadowing environmentalism and related concerns in the 20th and 21st centuries.

John Ruskin suffered a complete mental collapse on his final tour, which included Beauvais, Sallanches and Venice, in 1888.

John Ruskin attacked aspects of Darwinian theory with increasing violence, although he knew and respected Darwin personally.

John Ruskin's estate provided a site for more of his practical schemes and experiments: he had an ice house built, and the gardens comprehensively rearranged.

John Ruskin oversaw the construction of a larger harbour, and he altered the house.

John Ruskin built a reservoir and redirected the waterfall down the hills, adding a slate seat that faced the tumbling stream and craggy rocks rather than the lake, so that he could closely observe the fauna and flora of the hillside.

John Ruskin died at Brantwood from influenza on 20 January 1900 at the age of 80.

John Ruskin was buried five days later in the churchyard at Coniston, according to his wishes.

The centenary of John Ruskin's birth was keenly celebrated in 1919, but his reputation was already in decline and sank further in the fifty years that followed.

Brantwood was opened in 1934 as a memorial to John Ruskin and remains open to the public today.

In middle age, and at his prime as a lecturer, John Ruskin was described as slim, perhaps a little short, with an aquiline nose and brilliant, piercing blue eyes.

John Ruskin stammered a little at all times, and now, finding the ungracious words literally stick in his throat, sat down, leaving the remonstrance incomplete but clearly indicated.

Proust not only admired John Ruskin but helped translate his works into French, describing him as "for me one of the greatest writers of all times and of all countries".

John Ruskin commissioned sculptures and sundry commemorative items, and incorporated Ruskinian rose motifs in the jewellery produced by his cultured pearl empire.

John Ruskin established the Ruskin Society of Tokyo and his children built a dedicated library to house his Ruskin collection.

John Ruskin's work has been translated into numerous languages including, in addition to those already mentioned : German, Italian, Catalan, Spanish, Portuguese, Hungarian, Polish, Romanian, Swedish, Danish, Dutch, Czech, Chinese, Welsh, Esperanto, Gikuyu, and several Indian languages such as Kannada.

John Ruskin's Drawing Collection, a collection of 1470 works of art he gathered as learning aids for the John Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art, is at the Ashmolean Museum.

The Museum has promoted John Ruskin's art teaching, utilising the collection for in-person and online drawing courses.

John Ruskin was discussed in university extension classes, and in reading circles and societies formed in his name.

John Ruskin helped to inspire the settlement movement in Britain and the United States.

In Nazi Germany, John Ruskin was seen as an early British National Socialist.

In 2019, John Ruskin200 was inaugurated as a year-long celebration marking the bicentenary of John Ruskin's birth.

John Ruskin has designed and hand painted various friezes in honour of her ancestor and it is open to the public.

Notable John Ruskin enthusiasts include the writers Geoffrey Hill and Charles Tomlinson, and the politicians Patrick Cormack, Frank Judd, Frank Field and Tony Benn.

Jonathan Glancey at The Guardian and Andrew Hill at the Financial Times have both written about John Ruskin, as has the broadcaster Melvyn Bragg.

John Ruskin wrote over 250 works, initially art criticism and history, but expanding to cover topics ranging over science, geology, ornithology, literary criticism, the environmental effects of pollution, mythology, travel, political economy and social reform.

The range and quantity of John Ruskin's writing, and its complex, allusive and associative method of expression, cause certain difficulties.

John Ruskin believed that all great art should communicate an understanding and appreciation of nature.

John Ruskin was celebrating the Pre-Raphaelites, whose members, he said, had formed "a new and noble school" of art that would provide a basis for a thoroughgoing reform of the art world.

John Ruskin rejected the work of Whistler because he considered it to epitomise a reductive mechanisation of art.

John Ruskin praised the Gothic for what he saw as its reverence for nature and natural forms; the free, unfettered expression of artisans constructing and decorating buildings; and for the organic relationship he perceived between worker and guild, worker and community, worker and natural environment, and between worker and God.

Attempts in the 19th century to reproduce Gothic forms, attempts he had helped inspire, were not enough to make these buildings expressions of what John Ruskin saw as true Gothic feeling, faith, and organicism.

For John Ruskin, creating true Gothic architecture involved the whole community, and expressed the full range of human emotions, from the sublime effects of soaring spires to the comically ridiculous carved grotesques and gargoyles.

John Ruskin associated Classical values with modern developments, in particular with the demoralising consequences of the Industrial Revolution, resulting in buildings such as The Crystal Palace, which he criticised.

John Ruskin objected that forms of mass-produced faux Gothic did not exemplify his principles, but showed disregard for the true meaning of the style.

John Ruskin's ideas provided inspiration for the Arts and Crafts Movement, the founders of the National Trust, the National Art Collections Fund, and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings.

Clark neatly summarises the key features of John Ruskin's writing on art and architecture:.

John Ruskin never criticised Viollet-le-Duc's restoration work, just the idea of restoration.

John Ruskin wielded a critique of political economy of orthodox, 19th-century political economy principally on the grounds that it failed to acknowledge complexities of human desires and motivations.

John Ruskin began to express such ideas in The Stones of Venice, and increasingly in works of the later 1850s, such as The Political Economy of Art, but he gave them full expression in the influential and at the time of publication, very controversial essays, Unto This Last.

John Ruskin believed that the economic theories of Adam Smith, expressed in The Wealth of Nations had led, through the division of labour to the alienation of the worker not merely from the process of work itself, but from his fellow workmen and other classes, causing increasing resentment.

John Ruskin argued that one remedy would be to pay work at a fixed rate of wages, because human need is consistent and a given quantity of work justly demands a certain return.

John Ruskin was married once, to Effie Gray, whom he met when she was 12 and he was 21, and Gray's family encouraged a match between the two when she had matured.

Effie, in a letter to her parents, claimed that John Ruskin found her "person" repugnant:.

The cause of John Ruskin's "disgust" has led to much conjecture.

Lutyens argued that John Ruskin must have known the female form only through Greek statues and paintings of nudes which lacked pubic hair.

John Ruskin was her private art tutor, and the two maintained an educational relationship through correspondence until she was 18.

John Ruskin repeated his marriage proposal when Rose became 21, and legally free to decide for herself.

John Ruskin was willing to marry if the union would remain unconsummated, because her doctors had told her she was unfit for marriage; but Ruskin declined to enter another such marriage for fear of its effect on his reputation.

Tim Hilton, in his two-volume biography, asserts that Ruskin "was a paedophile", alluding by way of explanation to a sensual description by Ruskin of a half-naked girl he saw in Italy and quoting Ruskin's own statements about his liking for young girls, while John Batchelor argues that the term is inappropriate because Ruskin's behaviour does not "fit the profile".

John Ruskin was not a fan of buying low and selling high.