1.

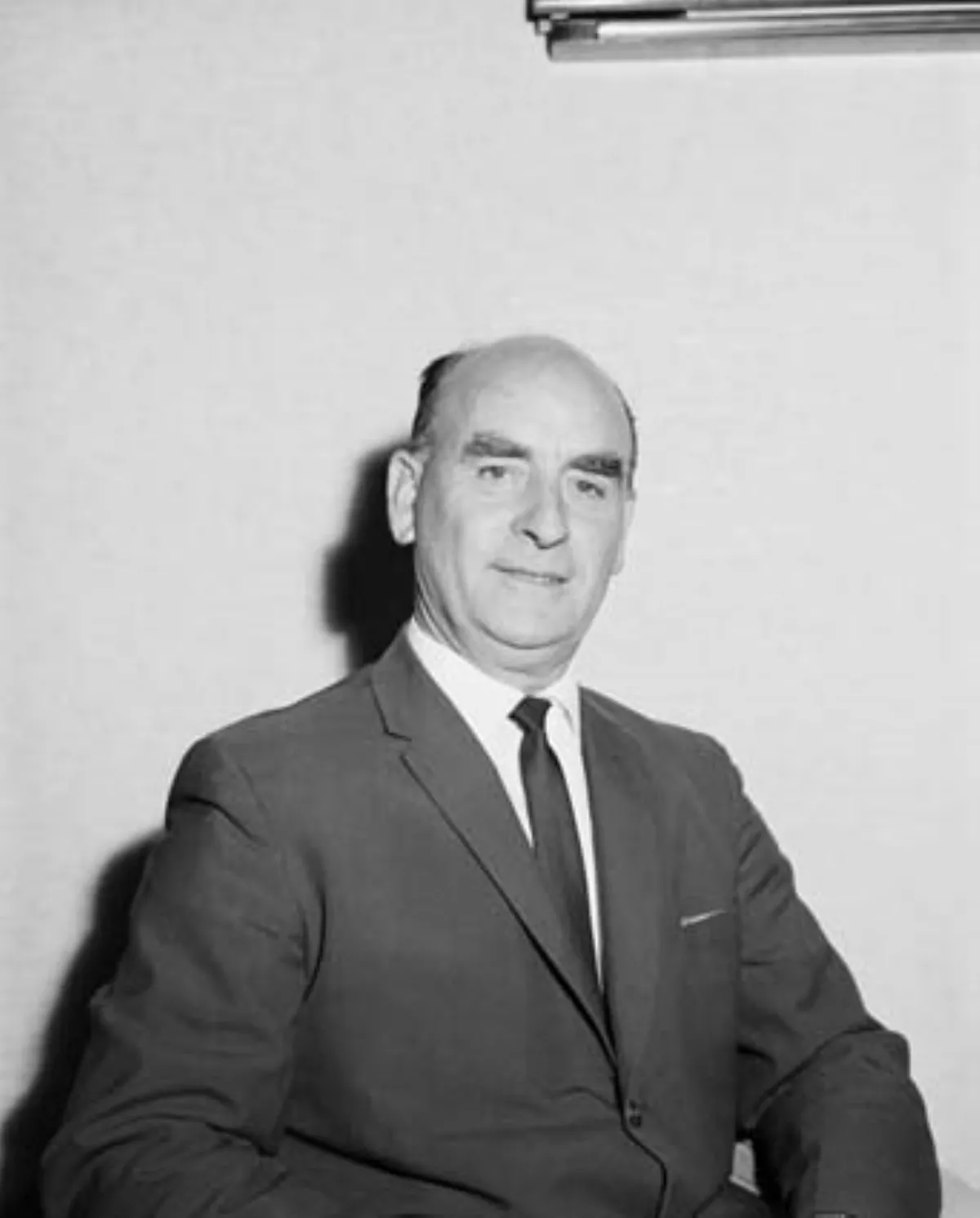

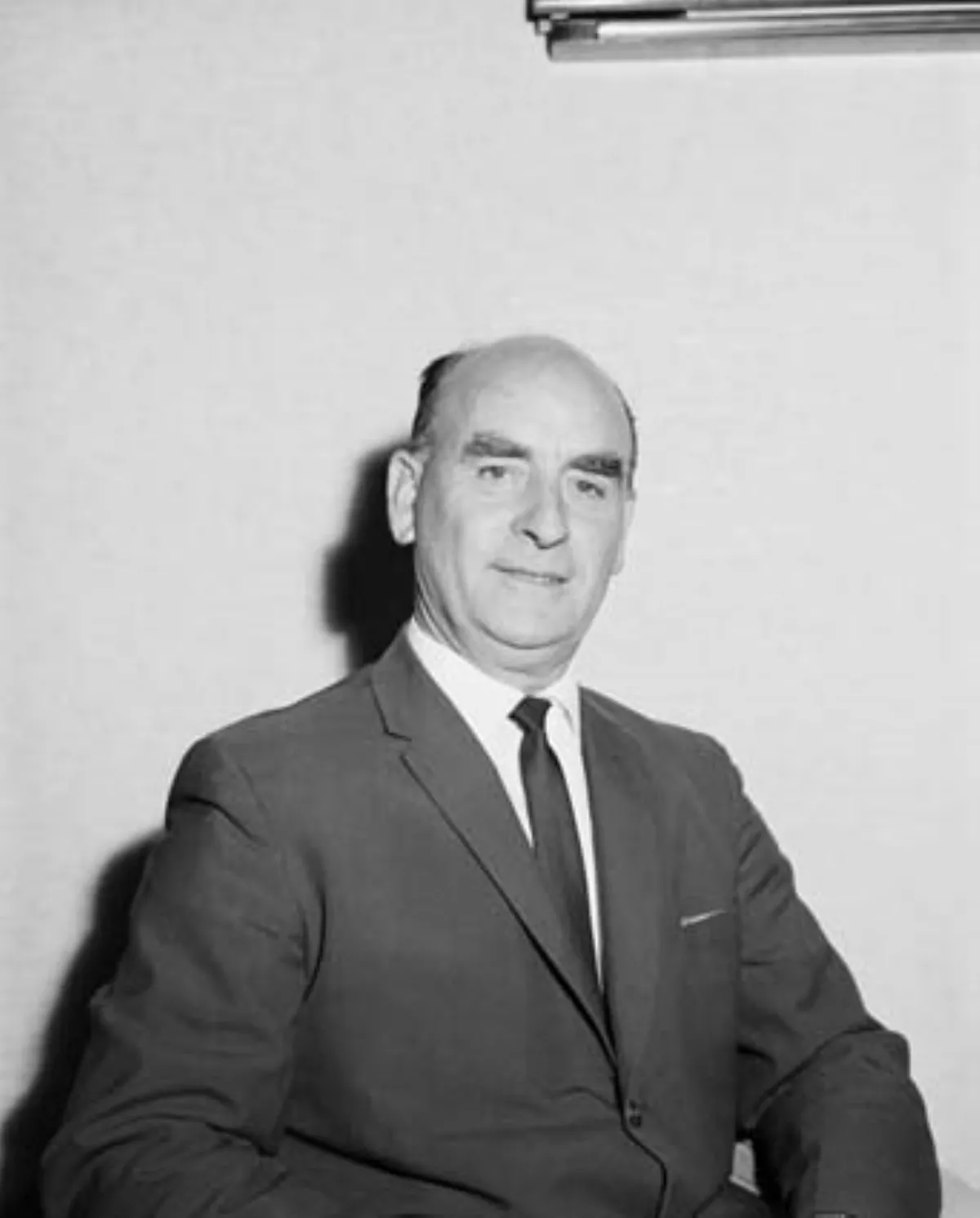

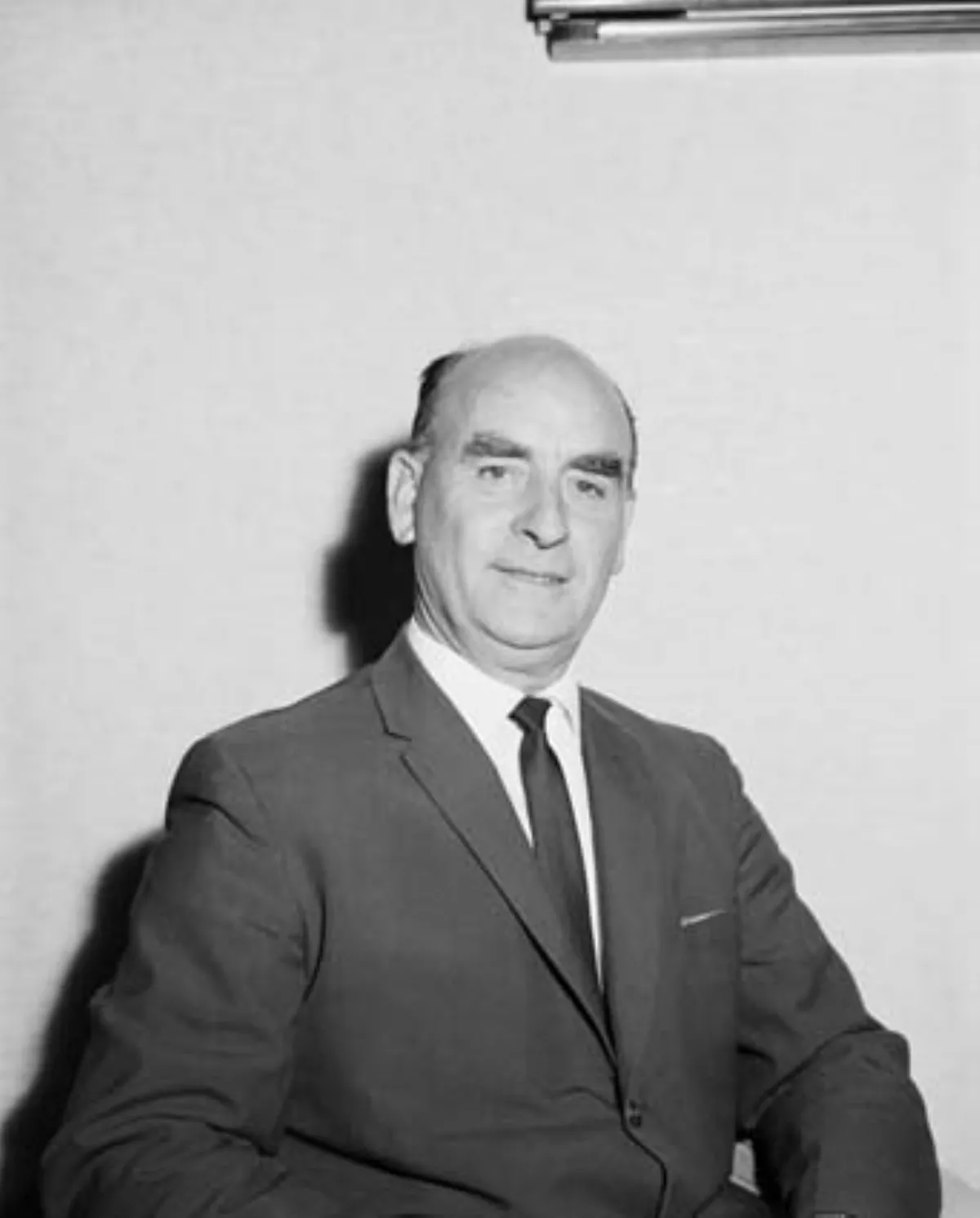

1. John Trezise Tonkin was an Australian politician who was the premier of Western Australia from 3 March 1971 to 8 April 1974.

1.

1. John Trezise Tonkin was an Australian politician who was the premier of Western Australia from 3 March 1971 to 8 April 1974.

John Tonkin's family moved several times before returning to Boulder, where he attended Boulder City Central School and Eastern Goldfields High School.

John Tonkin first served as a minister from 1943 to 1947.

John Tonkin held several portfolios during this time, the most important being education.

Labor lost the 1947 state election which resulted in John Tonkin losing his portfolios.

John Tonkin transferred to the electoral district of Melville when North-East Fremantle was abolished in 1950.

Tonkin was made a Companion of the Order of Australia in 1977, and has been honoured with the Tonkin Highway and John Tonkin College being named after him.

John Tonkin was born on 2 February 1902 in the town of Boulder, near Kalgoorlie, in the Goldfields of Western Australia.

John Tonkin's parents were engine driver John Trezise Tonkin and Julia, nee Carrigan, both of whom were born in Australia and had Cornish ancestry.

John Tonkin was the eldest of three surviving children and was brought up as a Methodist, although his mother was Catholic.

John Tonkin attended Boulder City Central School and Eastern Goldfields High School.

John Tonkin's father was a unionist and a supporter of the Australian Labor Party and Tonkin became interested in politics at a young age.

John Tonkin then taught at several small schools in the South West until 1930, including in Yallingup, Nuralingup, Margaret River, Kulin, Picton, Karnup, Hamel and Palgarup.

John Tonkin married Rosalie Maud Cleghorn at St Mary's Church in West Perth on 29 December 1926.

In 1930, they moved to Perth and John Tonkin taught at schools in North Perth and North Fremantle.

John Tonkin joined the Labor Party in 1923 and started a branch in Forest Grove.

John Tonkin unsuccessfully contested two seats in the Western Australian Legislative Assembly, the lower house of the Parliament of Western Australia: Sussex in 1927 and Murray-Wellington in 1930.

John Tonkin narrowly won the Labor Party's endorsement for the marginal Legislative Assembly seat of North-East Fremantle for the 1933 state election.

John Tonkin then defeated the minister for education, Hubert Parker, to become the first teacher to be elected to the Parliament of Western Australia.

Wise, Hawke and John Tonkin soon became leading members of the backbench, becoming known as the "three musketeers".

The Labor caucus elected Wise to the ministry in 1935 and Hawke in 1936, but John Tonkin had to wait until 1943 due to his lack of union or religious connections.

John Tonkin came close to losing in the 1936 state election, which led him to pay more attention to the needs of his constituency.

John Tonkin improved his skills in parliament and adjusted his approach to be less aggressive and more measured.

John Tonkin enlisted with the 25th Light Horse Regiment in October 1940, became a qualified signaller in January 1941, and joined the 11th Battalion in May 1941 upon being promoted to corporal.

In December 1941, he was called up for full-time deployment and the battalion was mobilised, but John Tonkin spent much of that time on leave without pay.

John Tonkin was promoted to sergeant in January 1942, and on 30 January 1942, he was discharged.

Curtin was the local member for Fremantle in the Australian House of Representatives and John Tonkin had a close working relationship with him.

In late 1942 and early 1943, John Tonkin supported Curtin's attempts to introduce conscription for soldiers to defend Australia.

Tonkin was elected and Premier John Willcock appointed him as minister for education, fulfilling a long-held dream of Tonkin's, and minister for social services, a newly-created position.

John Tonkin was asked to contest the 1945 Fremantle by-election after the death of Curtin, but he declined, wanting to remain involved in education in Western Australia.

When Willcock resigned and Wise became premier in July 1945, John Tonkin retained his ministry portfolios and took on the additional role of minister for agriculture.

John Tonkin saw his greatest achievements in education as being the merging of one-teacher schools, commonplace in rural areas, into larger schools; upgrading school facilities; reducing class sizes; and improving teacher training.

John Tonkin rejected calls from the opposition for the establishment of segregation between Aboriginal and white students, saying that he had observed from his teaching experience that Aboriginal children "learned just as well as the white children, and behaved just as well, in some cases even better".

Outside of parliament, John Tonkin was president of the East Fremantle Football Club from March 1947 to December 1953.

In 1955, John Tonkin became the first deputy premier as well.

John Tonkin had been in the role unofficially since the 1953 state election, and had been acting premier from May to July 1953 whilst Hawke was attending the coronation of Elizabeth II.

In July 1953, as acting premier and minister for works, John Tonkin announced plans to build a controlled-access highway between Perth and Kwinana to the south, which became known as the Kwinana Freeway.

John Tonkin was involved in planning and beginning the construction of the Narrows Bridge and interchange, which crossed the Swan River to link South Perth with the central business district, and the first stage of the Kwinana Freeway from the bridge to Canning Highway.

John Tonkin said that although he regretted it, the increase in car traffic required "some encroachment upon natural conditions".

John Tonkin announced a different name for the bridge in February 1959: the "Golden West Bridge".

The concessions John Tonkin offered to potential companies were criticised by the opposition as being too generous.

Hawke resigned in December 1966 and John Tonkin was elected party leader, thus becoming the leader of the opposition.

John Tonkin gained national attention when he emerged as a strong advocate for the Labor Party to drop its opposition to state aid for private schools, joining deputy federal Labor leader Gough Whitlam and many others who believed that the Labor Party could not be elected as long as it opposed it.

John Tonkin said that in Western Australia, funding for private schools, particularly Catholic schools, had eased the burden on the public school system and offered parents more choice in schools.

At the Labor Party's 1966 national conference at Surfers Paradise, Queensland, John Tonkin successfully persuaded the party to reverse its opposition to state aid for private schools.

John Tonkin managed to gain the support of mining entrepreneurs Lang Hancock and Peter Wright amidst a dispute between them and the minister for industrial development, Charles Court.

John Tonkin criticised Court's position and expressed support for Hancock and Wright, which resulted in the mining entrepreneurs donating to the Labor Party and giving the Labor Party favourable coverage in their newspaper, the Sunday Independent.

John Tonkin persistently criticised the Coalition government for being too secretive.

The twelve-man ministry was chosen by the Labor caucus and John Tonkin had the responsibility of allocating the specific ministerial positions.

John Tonkin himself was sworn in as the premier, minister for education, minister for environmental protection, and minister for cultural affairs, a new position.

Notably, John Tonkin did not choose to make himself treasurer, bucking the trend set by most previous premiers.

On 12 June 1971, John Tonkin married Winifred Joan West, a divorcee, at Wesley Church.

John Tonkin managed to secure A$5.6 million in federal funding at the premiers' conference in April 1971 which went some way towards getting the deficit to manageable levels.

John Tonkin announced that he would not be able to implement the election promises which required funding, to which Opposition Leader Brand responded by saying that John Tonkin should not have made such lavish promises when it was known the budget was in bad shape.

John Tonkin took the opportunity to appoint himself treasurer and give away the portfolios of education to Evans and environmental protection to Ron Davies, leaving himself with cultural affairs.

John Tonkin initially had a good relationship with Hancock and Wright, with John Tonkin going on a tour of their company Hanwright's mines in the Pilbara guided by Hancock and his cousin Valston Hancock.

John Tonkin wanted to make it easier for Hanwright to develop McCamey's Monster, an iron ore deposit.

However, officials at the mines department were opposed, and John Tonkin eventually agreed with them.

John Tonkin challenged this decision in the Supreme Court of Western Australia, but the Tonkin government passed an amendment to the mining act, changing the relevant law to ensure that Hanwright would lose.

The John Tonkin government implemented several reforms in industrial relations and employment.

In 1971, the John Tonkin government established a consumer protection bureau and the Parliamentary Inspector of Administrative Investigations, more commonly known as the ombudsman, the first of its kind in Australia.

In 1972, the John Tonkin government established the Environmental Protection Authority and significantly increased the number and size of national parks and reserves.

John Tonkin was socially conservative and disagreed with the Labor Party on issues including abortion.

John Tonkin overruled his party's policy by making his government officially opposed to legalising abortion.

John Tonkin was vocally against racism in sport and supported anti-apartheid protesters by speaking out against the South African rugby tour of Australia and proposed South African cricket tour of Australia.

John Tonkin was opposed to water fluoridation despite the scientific evidence supporting it and promised to end fluoridating Western Australia's water supplies.

When John Tonkin had been deputy premier in the Hawke government, he had sometimes intruded on Graham's responsibilities as minister for transport.

Graham had long-held ambitions to take over as leader from John Tonkin, and according to Mal Bryce, John Tonkin was determined to stay as leader at least until Graham retired.

John Tonkin faced threats from within his own party, who thought a younger cabinet was needed to win the upcoming election.

The Young Labor Organisation passed a motion of no confidence in John Tonkin and sent it to the Labor Party's state executive for consideration.

The Labor Party campaigned in the March 1974 state election under the slogan "Trust John Tonkin", highlighting his trustworthiness and reputation for integrity and stability.

John Tonkin was succeeded as premier by Charles Court on 8 April 1974.

John Tonkin continued on as opposition leader, heading the John Tonkin shadow ministry, the first formal shadow ministry in Western Australia.

John Tonkin resigned as leader on 15 April 1976 and chose not to contest his seat at the 1977 state election.

John Tonkin was succeeded in the seat of Melville by Barry Hodge and as the leader of the Labor Party by Colin Jamieson.

John Tonkin had served in parliament for 43 years, ten months and eleven days, making him the longest-serving member of the Parliament of Western Australia as of 2021.

John Tonkin died at Concorde Nursing Home in South Perth on 20 October 1995.

Former governor Francis Burt eulogised John Tonkin by saying that "he never generated cynicism or malice" and that "we always knew we could trust him".

John Tonkin cut the ribbon at that stage's opening ceremony on 1 May 1985.

The East Fremantle house which John Tonkin lived in from 1939 to 1989, a California bungalow on Preston Point Road, was assessed for placement on the State Register of Heritage Places in 2003, but the minister for heritage, Tom Stephens, directed that the house not be added to the register, against the advice of the Heritage Council of Western Australia.