1.

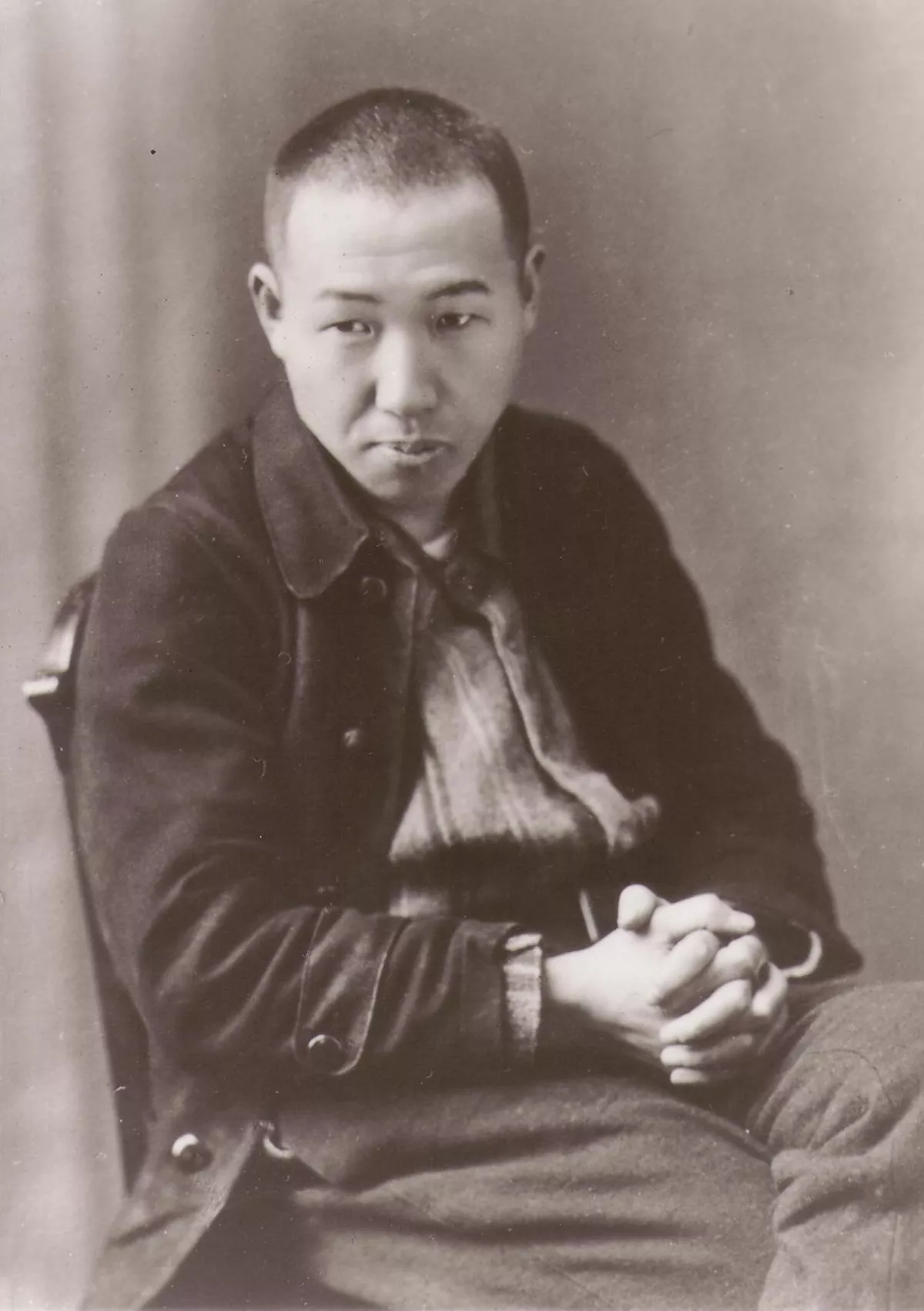

1. Kenji Miyazawa was a Japanese novelist, poet, and children's literature writer from Hanamaki, Iwate, in the late Taisho and early Showa periods.

1.

1. Kenji Miyazawa was a Japanese novelist, poet, and children's literature writer from Hanamaki, Iwate, in the late Taisho and early Showa periods.

Kenji Miyazawa was known as an agricultural science teacher, vegetarian, cellist, devout Buddhist, and utopian social activist.

Kenji Miyazawa founded the Rasu Farmers Association to improve the lives of peasants in Iwate Prefecture.

Kenji Miyazawa was interested in Esperanto and translated some of his poems into that language.

Almost totally unknown as a poet in his lifetime, Kenji Miyazawa's work gained its reputation posthumously, and enjoyed a boom by the mid-1990s on his centenary.

Kenji Miyazawa was born in the town of Hanamaki, Iwate, the eldest son of a wealthy pawnbroking couple, Masajiro and his wife Ichi.

Kenji Miyazawa was a keen student of natural history from an early age, and developed an interest as a teenager in poetry, coming under the influence of a local poet, Takuboku Ishikawa.

Kenji Miyazawa returned to Hanamaki due to the renewed illness of his beloved younger sister.

Kenji Miyazawa composed three poems on the day of her death, collectively entitled "Voiceless Lament".

Kenji Miyazawa found employment as a teacher in agricultural science at Hanamaki Agricultural High School.

Kenji Miyazawa managed to put out a collection of poetry, Haru to Shura in April 1924, thanks to some borrowings and a major grant from a producer of natto.

Kenji Miyazawa resigned his post as a teacher in 1926 to become a farmer and help improve the lot of the other farmers in the impoverished north-eastern region of Japan by sharing his theoretical knowledge of agricultural science, by imparting to them improved, modern techniques of cultivation.

Kenji Miyazawa taught his fellow farmers more general topics of cultural value, such as music, poetry, and whatever else he thought might improve their lives.

Kenji Miyazawa introduced them to classical music by playing to audiences compositions from Beethoven, Schubert, Wagner and Debussy on his gramophone.

Kenji Miyazawa introduced new agricultural techniques and more resistant strains of rice.

Not all of the local farmers were grateful for his efforts, with some sneering at the idea of a city-slicker playing farmer, and others expressing disappointment that the fertilizers Kenji Miyazawa introduced were not having the desired effects.

Kenji Miyazawa in turn did not hold an ideal view of the farmers; in one of his poems he describes how a farmer bluntly tells him that all his efforts have done no good for anyone.

Kenji Miyazawa was a prolific writer of children's stories, many of which appear superficially light or humorous but include messages intended for the moral education of the reader.

Kenji Miyazawa wrote some works in prose and some stage plays for his students and left behind a large amount of tanka and free verse, most of which was discovered and published posthumously.

Kenji Miyazawa fell ill in summer 1928, and by the end of that year this had developed into acute pneumonia.

Kenji Miyazawa struggled with pleurisy for many years and was sometimes incapacitated for months at a time.

Kenji Miyazawa's health improved nonetheless sufficiently for him to take on consultancy work with a rock-crushing company in 1931.

Kenji Miyazawa died the following day, having been exhausted by the length of his discussion with the farmers.

Kenji Miyazawa left his manuscripts to his younger brother Seiroku, who kept them through the Pacific War and eventually had them published.

Kenji Miyazawa started writing poetry as a schoolboy, and composed over a thousand tanka beginning at roughly age 15, in January 1911, a few weeks after the publication of Takuboku's "A Handful of Sand".

Kenji Miyazawa favoured this form until the age of 24.

Kenji Miyazawa was removed physically from the poetry circles of his day.

Kenji Miyazawa was an avid reader of modern Japanese poets such as Hakushu Kitahara and Sakutaro Hagiwara, and their influence can be traced on his poetry, but his life among farmers has been said to have influenced his poetry more than these literary interests.

Kenji Miyazawa's works were influenced by contemporary trends of romanticism and the proletarian literature movement.

Kenji Miyazawa edited a volume of extracts from Nichiren's writings, the year before he join the Kokuchukai.

Kenji Miyazawa largely abandoned tanka by 1921, and turned his hand instead to the composition of free verse, involving an extension of the conventions governing tanka verse forms.

Kenji Miyazawa is said to have written three thousand pages a month worth of children's stories during this period, thanks to the advice of a priest in the Nichiren order, Takachiyo Chiyo.

Keene remarks that the speed at which Kenji Miyazawa composed these poems was characteristic of the poet, as a few months prior he had composed three long poems, one more than 900 lines long, in three days.

Several lines uttered by his sister are written in a regional dialect so unlike Standard Japanese that Kenji Miyazawa provided translations at the end of the poem.

The poem lacks any kind of regular meter, but draws its appeal from the raw emotion it expresses; Keene suggests that Kenji Miyazawa learned this poetic technique from Sakutaro Hagiwara.

Kenji Miyazawa could write a huge volume of poetry in a short time, based mostly on impulse, seemingly with no preconceived plan of how long the poem would be and without considering future revisions.

Kenji Miyazawa wrote his most famous poem, "Ame ni mo makezu", in his notebook on November 3,1931.

Keene was dismissive of the poetic value of the poem, stating that it is "by no means one of Miyazawa's best poems" and that it is "ironic that [it] should be the one poem for which he is universally known", but that the image of a sickly and dying Kenji writing such a poem of resolute self-encouragement is striking.

Kenji Miyazawa wrote a great number of children's stories, many of them intended to assist in moral education.

In 1919, Kenji Miyazawa edited a volume of extracts from the writings of Nichiren, and in December 1925 a solicitation to build a Nichiren temple in the Iwate Nippo under a pseudonym.

Kenji Miyazawa was born into a family of Pure Land Buddhists, but in 1915 converted to Nichiren Buddhism upon reading the Lotus Sutra and being captivated by it.

Kenji Miyazawa's conversion created a rift with his relatives, but he nevertheless became active in trying to spread the faith of the Lotus Sutra, walking the streets crying Namu Myoho Renge Kyo.

The general consensus among modern Kenji Miyazawa scholars is that he became estranged from the group and rejected their nationalist agenda, but a few scholars such as Akira Ueda, Gerald Iguchi and Jon Holt argue otherwise.

Kenji Miyazawa remained a devotee of the Lotus Sutra until his death.

Kenji Miyazawa made a deathbed request to his father to print one thousand copies of the sutra in Japanese translation and distribute them to friends and associates.

Kenji Miyazawa incorporated a relatively large amount of Buddhist vocabulary in his poems and children's stories.

Kenji Miyazawa drew inspiration from mystic visions in which he saw the bodhisattva Kannon, the Buddha himself and fierce demons.

In 1925 Kenji Miyazawa pseudonymously published a solicitation to build a Nichiren temple in Hanamaki, which led to the construction of the present Shinshoji, but on his death his family, who were followers of Pure Land Buddhism, had him interred at a Pure Land temple.

Kenji Miyazawa's family converted to Nichiren Buddhism in 1951 and moved his grave to Shinshoji, where it is located today.

Kenji Miyazawa practiced vegetarianism during two periods: for five years from 1918 after becoming a Lotus Sutra devotee, and from April 1926 until his death.

Kenji Miyazawa stored rice in the well, eating it frozen in winter, with sides such as fried tofu, pickles, or tomatoes.

Kenji Miyazawa loved his native province, and the mythical landscape of his fiction, known by the generic neologism, coined in a poem in 1923, as Ihatobu is often thought to allude to Iwate.

Kenji Miyazawa's poetry managed to attract some attention during his lifetime.

Kenji Miyazawa sought Burton Watson's opinion, and Watson, a scholar of Chinese classics trained at the University of Kyoto, recommended Kenji.

Snyder's translations of eighteen poems by Kenji Miyazawa appeared in his collection, The Back Country.

The Miyazawa Kenji Museum was opened in 1982 in his native Hanamaki, in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of his death.

The 2015 anime Punch Line and its video game adaptation feature a self-styled hero who calls himself Kenji Miyazawa and has a habit of quoting his poetry when arriving on scene.