1.

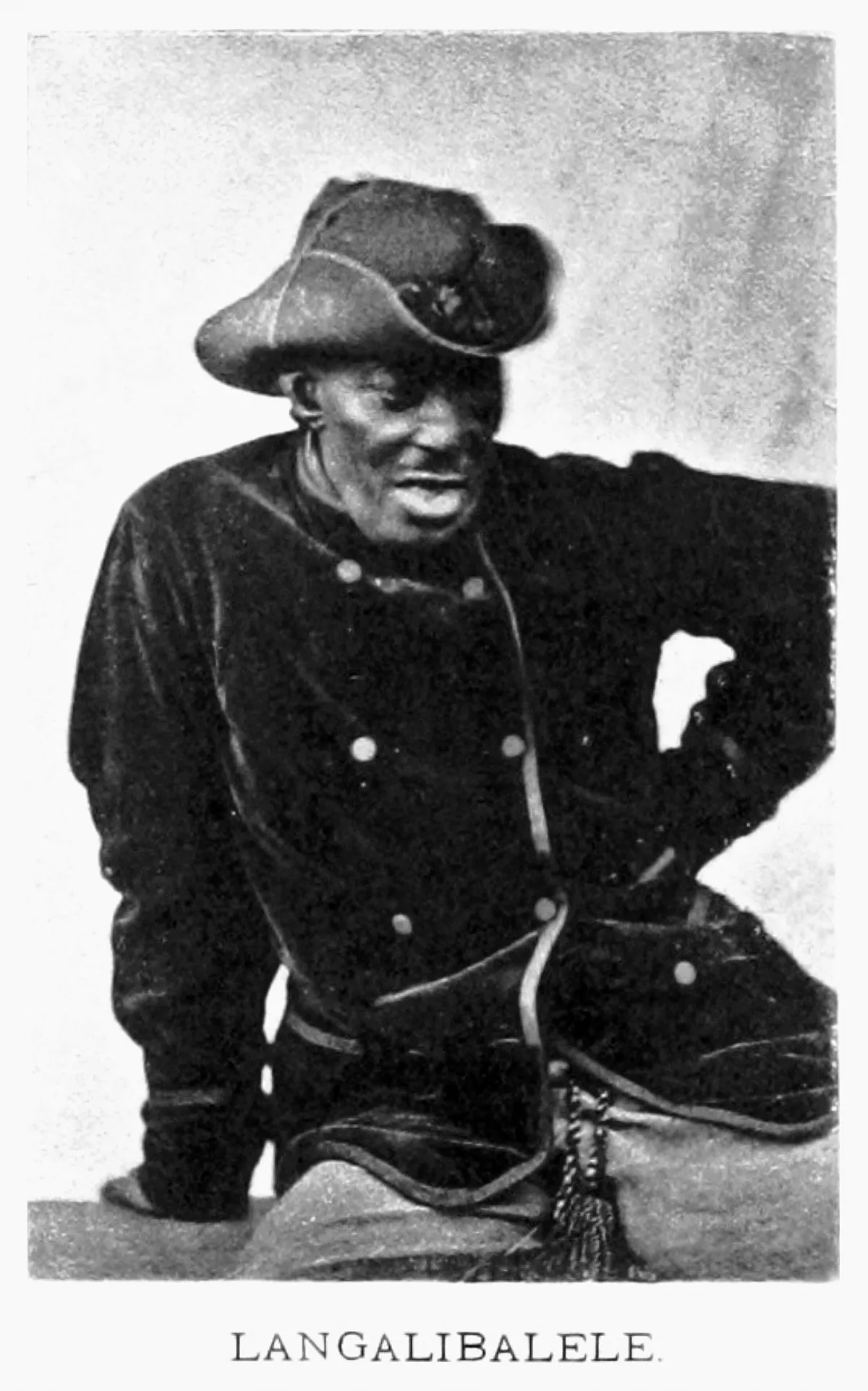

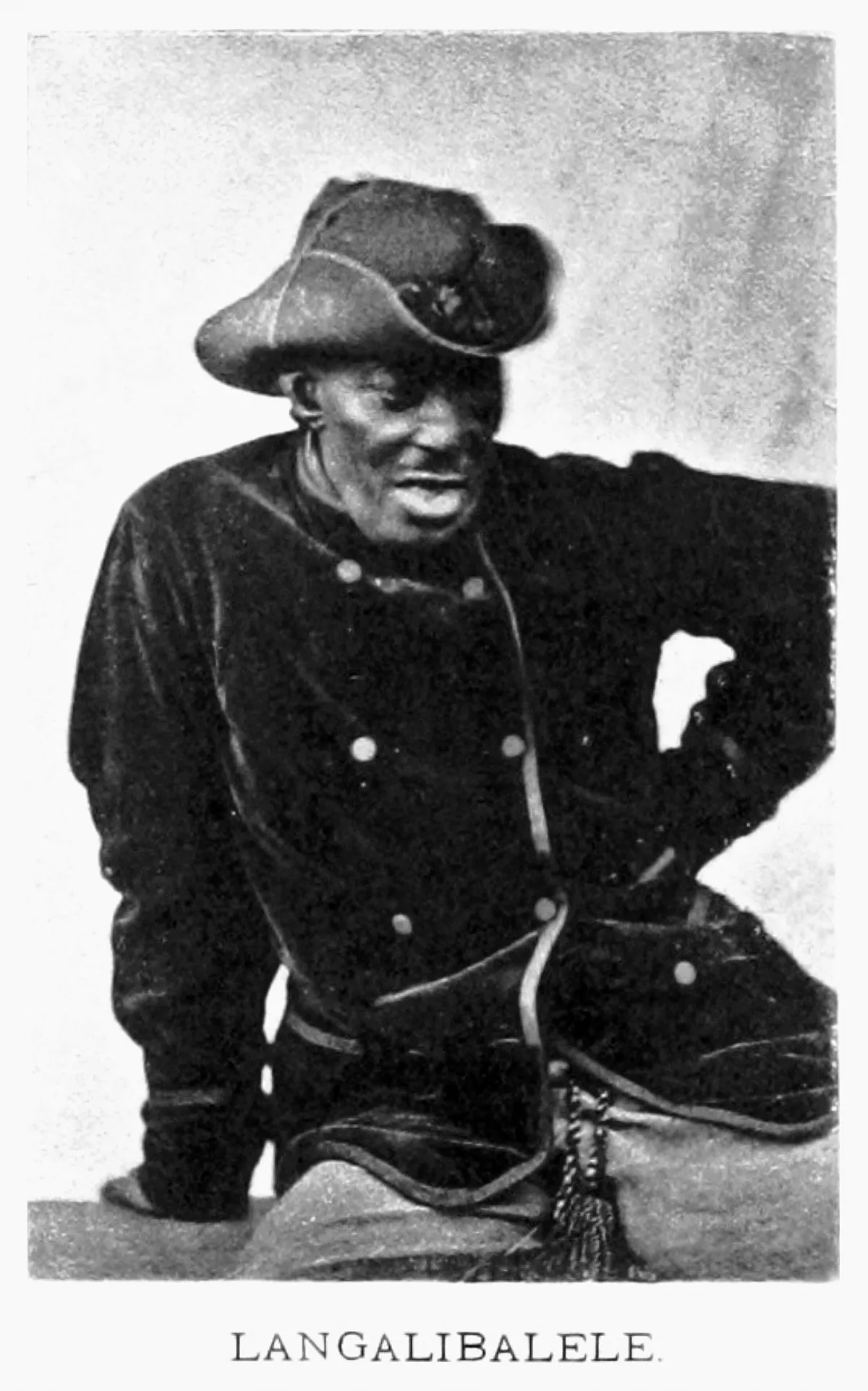

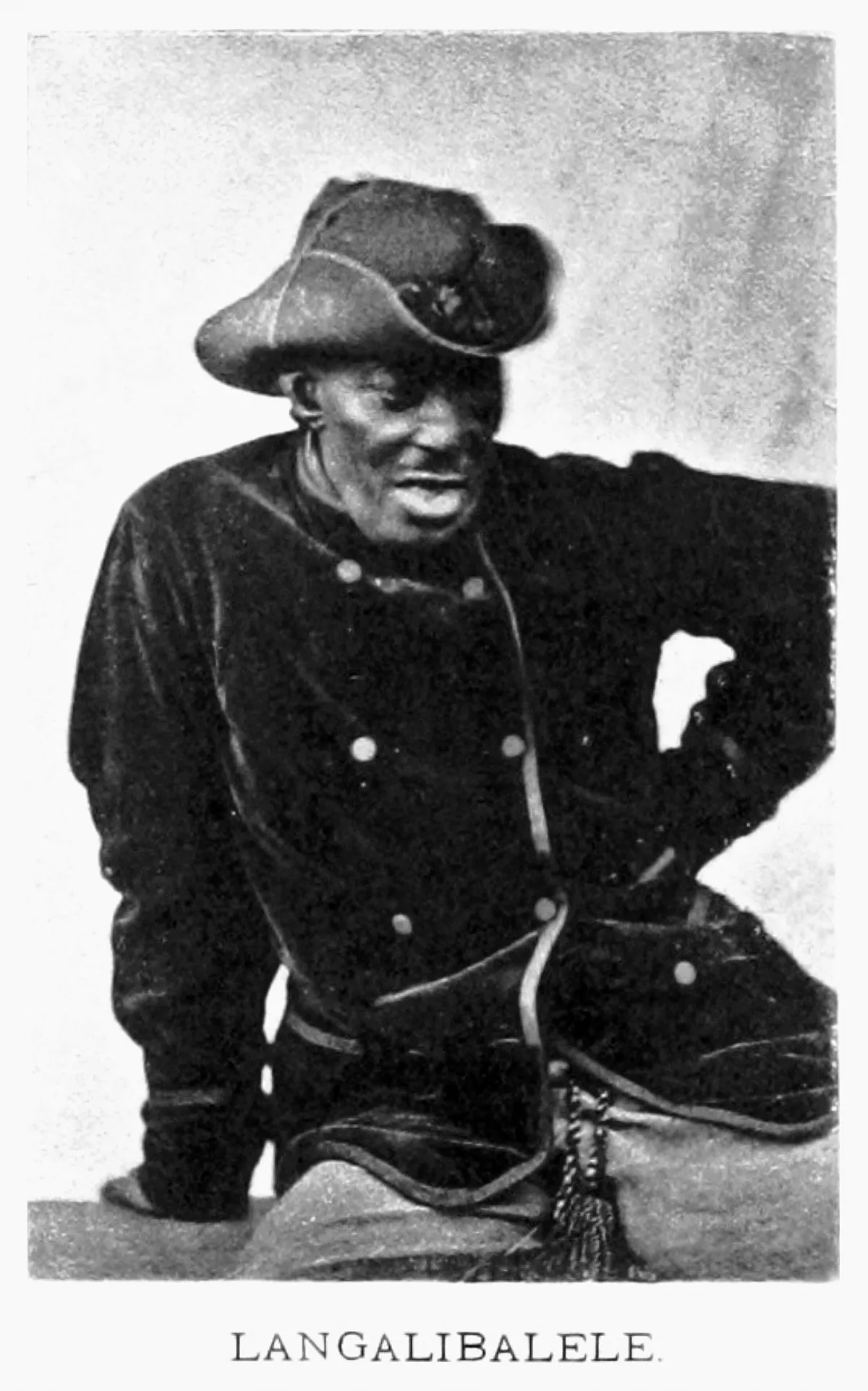

1. Langalibalele was born on the edge of the arrival of European settlers in the province.

1.

1. Langalibalele was born on the edge of the arrival of European settlers in the province.

In 1879 the colonial authorities of Natal demanded that the guns be registered; Langalibalele refused and a stand-off ensued, resulting in a violent skirmish in which British troops were brutally killed.

Langalibalele ran across the mountains into Basutoland, but was kidnapped, tried and banished to Robben Island.

Langalibalele's imprisonment was a watermark in South African political history that split the colonial population of the Colony of Natal.

At the time of King Langalibalele I's birth, European settlements in Southern Africa were confined to the British controlled Cape Colony and to the Portuguese fortress of Lourenco Marques.

King Langalibalele I, He was the second son of King Mthimkhulu II who was born in 1818 and was originally known as Prince Midinga.

King Dingane however ordered the murder of King Dlomo III in 1839, a year before his own death, so that Prince Langalibalele I became king of the AmaHlubi.

Under the guidance of Zimane, the great man in the AmaHlubi kingdom, that King Langalibalele I was circumcised and initiated into the rituals of the kingdom.

King Langalibalele I had a long history of escapes including escaping being killed by the AmaZulu Clan.

Walker records that the government named eight men who were to be ordered to register their guns and that after some hesitation, Langalibalele sent in five of the named eight men.

Pearse on the other hand records that Langalibalele himself was ordered to appear before Shepstone, the Secretary for Native Affairs and that Langalibalele refused on grounds of ill health.

The trial of Langalibalele started on 16 January 1874 and was described by Pearse as a "disgrace to British justice".

Langalibalele was tried under native law with Pine and Shepstone, the chief accusers presiding over the court without the assistance of a Supreme Court judge.

Langalibalele was denied the right to have a counsel until the third day of the trial, the counsel was not permitted to interview the prisoner nor was he permitted to cross-examine the witnesses.

Langalibalele was sentenced to banishment for life and as the Colony of Natal had no suitable place of detention, the neighbouring Cape Colony to the west was prevailed upon to make Robben Island available for Langalibalele's imprisonment.

Almost immediately after Langalibalele arrived at Robben island, information began to surface across southern Africa about the unfair nature of the Chief's treatment.

Doubts were soon raised about the fairness of the trial, and about whether Langalibalele actually intended to rebel at all.

Langalibalele journeyed to England to plead Langalibalele's case personally and succeeded in getting the case returned to the South African courts.

Langalibalele explained that his personal interest in the case was the protection that he had received from Langalibilele's namesake during the latter stages of his journey to Lourenco Marques.

The ruling government of the semi-independent Cape Colony soon came to the conclusion that Langalibalele had been unjustly sentenced, though much of the Cape's legislature on the other hand remained wary of the Hlubi chief.

The resulting bill to have Langalibalele released from Robben island faced opposition in the Cape's Legislature, and only succeeded when the Cape Prime Minister himself threatened to resign if it was not passed.

The pressure to reconsider the sentence grew, and in August 1875, after Carnarvon, the Colonial Secretary had finally referred the case back to the courts in the Cape Colony, Langalibalele was allowed to leave Robben Island.

Langalibalele was obliged to remain in the Cape Colony for the time being, until 1887 when he was permitted to return to Natal.

Langalibalele never regained his power as leader of the Hlubi; he died in 1889 and was buried at Ntabamhlope, 25 kilometres west of Estcourt.

The immediate reaction to the failure to apprehend Langalibalele was an improvement in the colony's security and the search for a scapegoat.

Security was improved by the Governor of the Cape Colony, Sir Henry Barkly, sending a contingent of 200 men to Natal while both the neighbouring Boer Republics mobilised men to prevent Langalibalele seeking help for the Zulu king Cetshwayo.

One of the underlying causes of the Langalibalele "rebellion" was an inconsistent policy in the various British colonies towards the native populations and in particular the ownership of guns.

Langalibalele's legacy continued into the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

In 2005 the amaHlubi people presented a Submission to the Commission on Traditional Leadership Disputes and Claims under the Framework Act to recognise Ingonyama Muziwenkosi ka Tatazela ka Siyephu ka Langalibalele, otherwise known as Langalibalele II as king of the amaHlubi.