1.

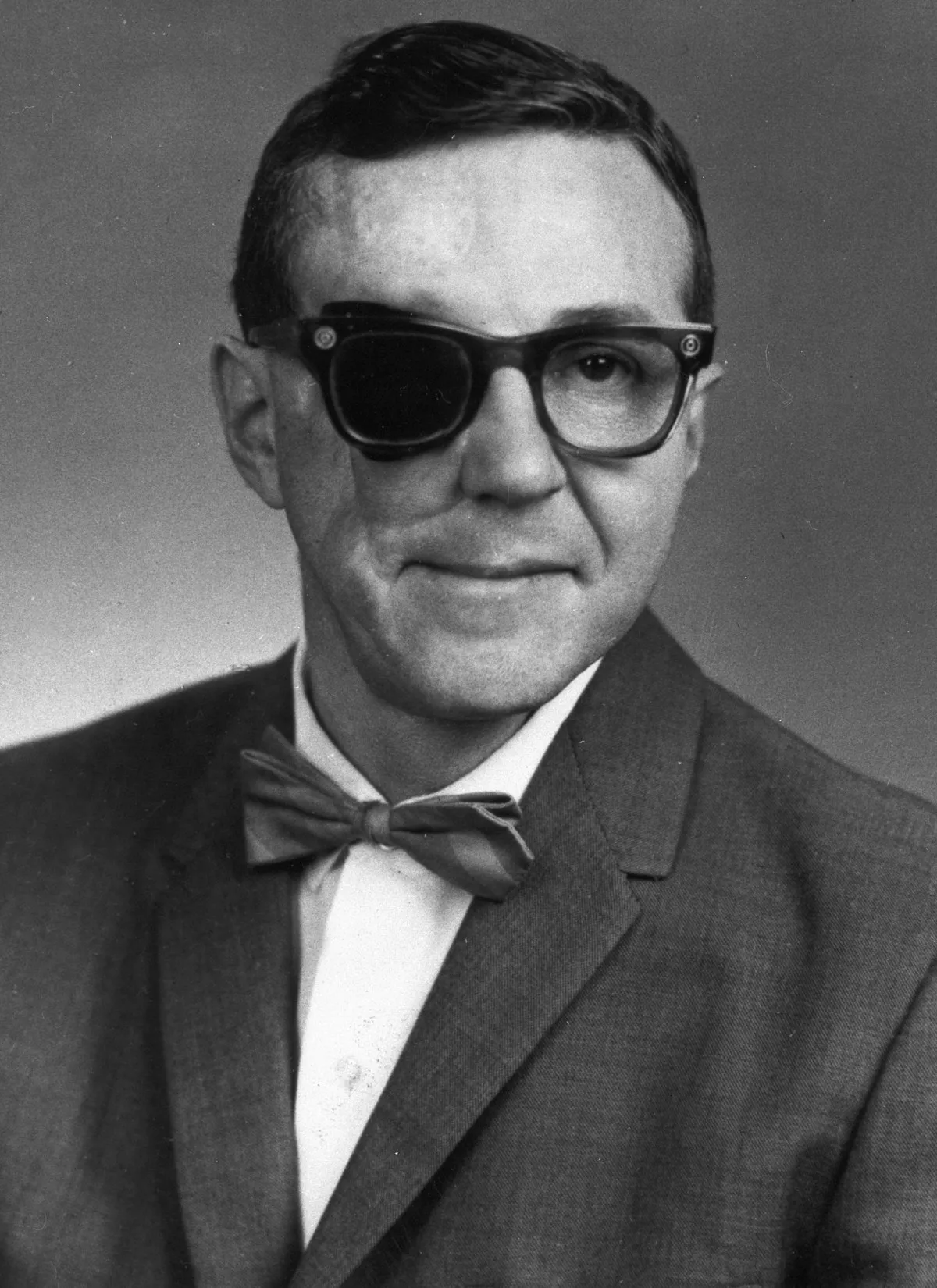

1. Leo Brewer joined the Manhattan Project following his graduate work, and joined the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley in 1946.

1.

1. Leo Brewer joined the Manhattan Project following his graduate work, and joined the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley in 1946.

Leo Brewer died in 2005 as a result of Beryllium poisoning from his work in World War II.

Leo Brewer spent the first ten years of his life with his family in Youngstown, Ohio, where his father worked as a shoe repairman.

In 1946, following his service as a member of the Manhattan Project, Leo Brewer was appointed an assistant professor in the department of chemistry at the University of California.

Leo Brewer rose steadily through the ranks, achieving the rank of full professor in 1955.

Leo Brewer served as a faculty member of the department of chemistry for over sixty years, during which time he directed 41 Ph.

Besides providing classroom instruction in solid-state chemistry, heterogeneous equilibria, and inorganic chemistry, Leo Brewer delivered lectures and supervised laboratory work for laboratory courses in freshman chemistry, advanced quantitative analysis, instrumental analysis, inorganic synthesis, inorganic reactions, and organic chemistry, as well as courses in chemical thermodynamics from the sophomore to graduate student level.

Leo Brewer was a caring and gifted teacher who was greatly admired by students and colleagues alike.

Leo Brewer was instrumental in founding the National Academy of Sciences' National Research Council Committee on High-Temperature Chemistry, as well as organizing the first Gordon Research Conference on High-Temperature Chemistry in 1960.

At the request of the Atomic Energy Commission and its successors, the Energy Research and Development Administration, and the Department of Energy, Leo Brewer worked on numerous committees, including the DOE Council for Materials Sciences and the DOE Selection Committee for the Fermi Award.

Leo Brewer maintained close ties with organizations that represented the international scientific community, including the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, and the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Besides his distinguished career as a chemist and educator, Leo Brewer was an avid gardener who held a keen interest in native California plant life.

Outside of his editorial work, Leo Brewer authored nearly 200 articles on a variety of advanced topics in the field of thermodynamics.

Leo Brewer was involved at different points in his career with astrophysics and ceramics.

Leo Brewer showed that when vapor and condensed phases are in equilibrium, the vapor species become more complex as the temperature is raised.

Leo Brewer's rule became the foundation of the field of high-temperature chemistry.

Leo Brewer devoted major effort to the characterization of the thermodynamic properties at high temperatures, and the critical evaluations of the thermodynamic properties from the Manhattan Project were updated periodically.

Leo Brewer conducted a wide range of spectroscopic studies both at high temperatures and in matrices to fix the thermodynamic properties of high-temperature vapors.

From 1950 to 1970, Leo Brewer published many papers on the analysis of the spectra produced by high-temperature gaseous molecules.

When low temperature matrix isolation was developed by George Pimentel at UC Berkeley, Leo Brewer produced many papers on the spectra of his high-temperature molecules in a frozen inert matrix.

Leo Brewer had a long-term interest in the electronic states of I2, and he had several papers on its remarkable complexities.

Leo Brewer extended this concept to include the nature of d and f electrons, and the concept of acid-base interactions.

Over several years Leo Brewer developed the Leo Brewer-Engel theory for such bonds, and he published many papers about its application.

Leo Brewer served as a Guggenheim Fellow and as an elected member of the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the American Society for Metals.

Leo Brewer believed that this was caused by some of his work with toxic or radioactive chemicals.