1.

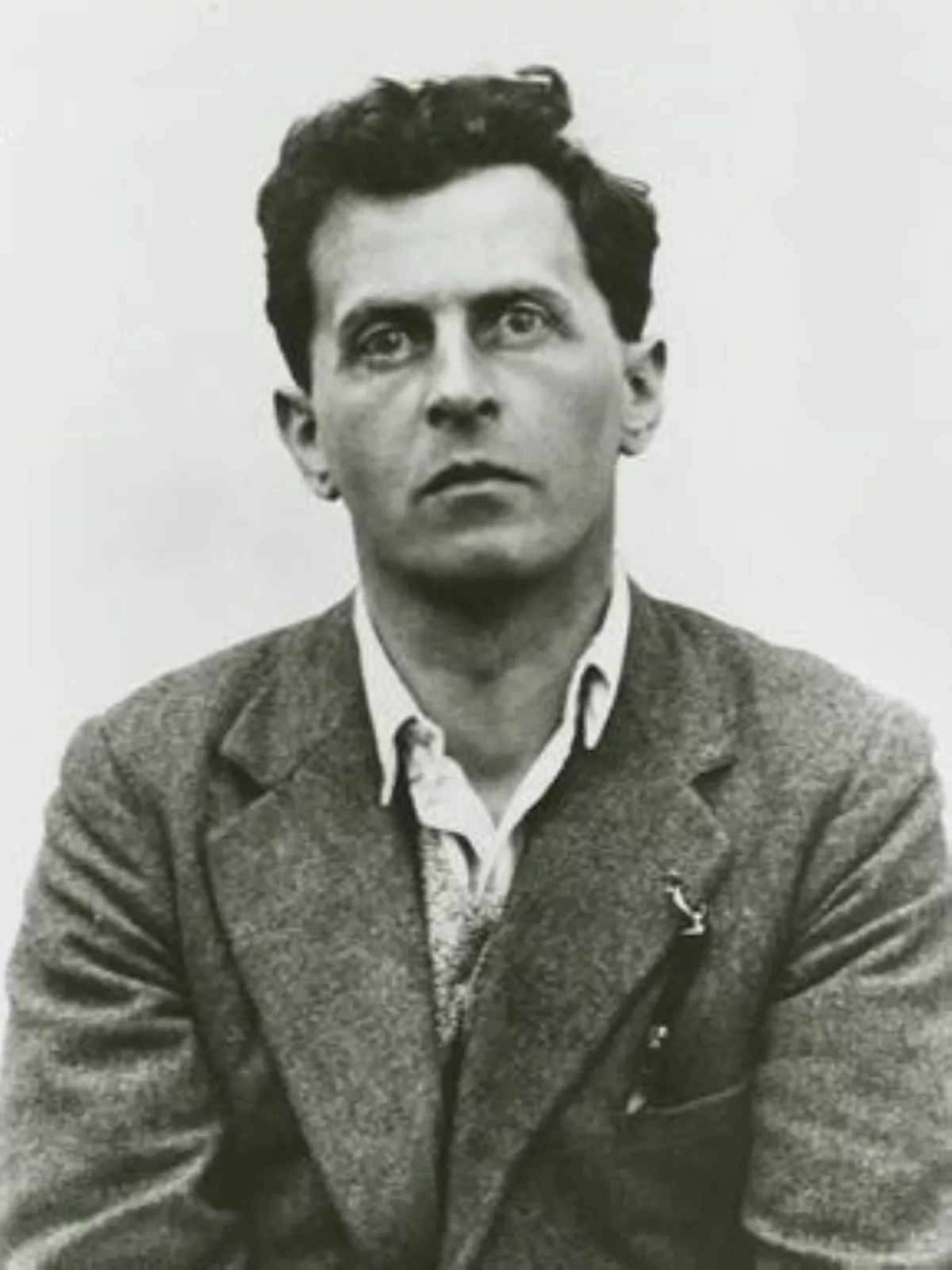

1. From 1929 to 1947, Wittgenstein taught at the University of Cambridge.

1.

1. From 1929 to 1947, Wittgenstein taught at the University of Cambridge.

Ludwig Wittgenstein's philosophy is often divided into an early period, exemplified by the Tractatus, and a later period, articulated primarily in the Philosophical Investigations.

The "early Ludwig Wittgenstein" was concerned with the logical relationship between propositions and the world, and he believed that by providing an account of the logic underlying this relationship, he had solved all philosophical problems.

The "later Ludwig Wittgenstein" rejected many of the assumptions of the Tractatus, arguing that the meaning of words is best understood as their use within a given language game.

Ludwig Wittgenstein's grandmother Fanny was a first cousin of the violinist Joseph Joachim.

Karl Otto Clemens Ludwig Wittgenstein became an industrial tycoon, and by the late 1880s was one of the richest men in Europe, with an effective monopoly on Austria's steel cartel.

Karl Ludwig Wittgenstein was viewed as the Austrian equivalent of Andrew Carnegie, with whom he was friends, and was one of the wealthiest men in the world by the 1890s.

Ludwig Wittgenstein's mother was Leopoldine Maria Josefa Kalmus, known among friends as "Poldi".

Ludwig Wittgenstein, who valued precision and discipline, never considered contemporary classical music acceptable.

Ludwig Wittgenstein himself had absolute pitch, and his devotion to music remained vitally important to him throughout his life; he made frequent use of musical examples and metaphors in his philosophical writings, and he was unusually adept at whistling lengthy and detailed musical passages.

Ludwig Wittgenstein learnt to play the clarinet in his 30s.

Ludwig Wittgenstein had asked the pianist to play Thomas Koschat's "Verlassen, verlassen, verlassen bin ich", before mixing himself a drink of milk and potassium cyanide.

Ludwig Wittgenstein had left several suicide notes, one to his parents that said he was grieving over the death of a friend, and another that referred to his "perverted disposition".

Ludwig Wittgenstein's father forbade the family from ever mentioning his name again.

On starting at the Realschule, Ludwig Wittgenstein had been moved forward a year.

Ludwig Wittgenstein had particular difficulty with spelling and failed his written German exam because of it.

Ludwig Wittgenstein was baptized as an infant by a Catholic priest and received formal instruction in Catholic doctrine as a child, as was common at the time.

Ludwig Wittgenstein nevertheless believed in the importance of the idea of confession.

Ludwig Wittgenstein discussed it with Gretl, his other sister, who directed him to Schopenhauer's The World as Will and Representation.

In later years, Ludwig Wittgenstein was highly dismissive of Schopenhauer, describing him as an ultimately "shallow" thinker:.

In 1912, Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote to Russell saying that Mozart and Beethoven were the actual sons of God.

Ludwig Wittgenstein's religious belief emerged during his service for the Austrian army in World War I, and he was a devoted reader of Dostoevsky's and Tolstoy's religious writings.

Ludwig Wittgenstein viewed his wartime experiences as a trial in which he strove to conform to the will of God, and in a journal entry from 29 April 1915, he writes:.

Around this time, Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote that "Christianity is indeed the only sure way to happiness", but he rejected the idea that religious belief was merely thinking that a certain doctrine was true.

From this time on, Ludwig Wittgenstein viewed religious faith as a way of living and opposed rational argumentation or proofs for God.

Many years later, as a professor at the University of Cambridge, Ludwig Wittgenstein distributed copies of Weininger's book to his bemused academic colleagues.

Ludwig Wittgenstein said that Weininger's arguments were wrong, but that it was the way they were wrong that was interesting.

Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote: 'The saint is the only Jewish "genius".

Ludwig Wittgenstein and Hitler were born just six days apart, though Hitler had to re-sit his mathematics exam before being allowed into a higher class, while Ludwig Wittgenstein was moved forward by one, so they ended up two grades apart at the Realschule.

Ludwig Wittgenstein's was a self-doubting Judaism, which had always the possibility of collapsing into a destructive self-hatred but which held an immense promise of innovation and genius.

Ludwig Wittgenstein began his studies in mechanical engineering at the Technische Hochschule Berlin in Charlottenburg, Berlin, on 23 October 1906, lodging with the family of Professor Jolles.

Ludwig Wittgenstein attended for three semesters, and was awarded a diploma on 5 May 1908.

Ludwig Wittgenstein arrived at the Victoria University of Manchester in the spring of 1908 to study for a doctorate, full of plans for aeronautical projects, including designing and flying his own plane.

Ludwig Wittgenstein conducted research into the behaviour of kites in the upper atmosphere, experimenting at a meteorological observation site near Glossop in Derbyshire.

At Glossop, Ludwig Wittgenstein worked under Professor of Physics Sir Arthur Schuster.

Ludwig Wittgenstein worked on the design of a propeller with small jet engines on the end of its blades, something he patented in 1911, and that earned him a research studentship from the university in the autumn of 1908.

Ludwig Wittgenstein's design required air and gas to be forced along the propeller arms to combustion chambers on the end of each blade, where they were then compressed by the centrifugal force exerted by the revolving arms and ignited.

Work on the jet-powered propeller proved frustrating for Ludwig Wittgenstein, who had very little experience working with machinery.

Ludwig Wittgenstein decided instead that he needed to study logic and the foundations of mathematics, describing himself as in a "constant, indescribable, almost pathological state of agitation".

Ludwig Wittgenstein was not only attending Russell's lectures but dominating them.

Ludwig Wittgenstein started following him after lectures back to his rooms to discuss more philosophy, until it was time for the evening meal in Hall.

Ludwig Wittgenstein maintained, for example, at one time that all existential propositions are meaningless.

Ludwig Wittgenstein later told David Pinsent that Russell's encouragement had proven his salvation, and had ended nine years of loneliness and suffering, during which he had continually thought of suicide.

The role-reversal between Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein was such that Russell wrote in 1916 after Ludwig Wittgenstein had criticized Russell's own work:.

Ludwig Wittgenstein's [Wittgenstein's] criticism, tho' I don't think you realized it at the time, was an event of first-rate importance in my life, and affected everything I have done since.

Ludwig Wittgenstein dominated the society and for a time would stop attending in the early 1930s after complaints that he gave no one else a chance to speak.

Accounts vary as to what happened next, but Ludwig Wittgenstein apparently started waving a hot poker, demanding that Popper give him an example of a moral rule.

Popper maintained that Ludwig Wittgenstein "stormed out", but it had become accepted practice for him to leave early.

The economist John Maynard Keynes invited him to join the Cambridge Apostles, an elite secret society formed in 1820, which both Bertrand Russell and G E Moore had joined as students, but Wittgenstein did not greatly enjoy it and attended only infrequently.

Ludwig Wittgenstein was admitted in 1912 but resigned almost immediately because he could not tolerate the style of discussion.

Nevertheless, the Cambridge Apostles allowed Ludwig Wittgenstein to participate in meetings again in the 1920s when he returned to Cambridge.

Reportedly, Ludwig Wittgenstein had trouble tolerating the discussions in the Cambridge Moral Sciences Club.

Ludwig Wittgenstein was quite vocal about his depression in his years at Cambridge and before he went to war; on many an occasion, he told Russell of his woes.

Ludwig Wittgenstein made numerous remarks to Russell about the logic driving him mad.

Ludwig Wittgenstein stated to Russell that he "felt the curse of those who have half a talent".

Ludwig Wittgenstein later expressed this same worry and told of being in mediocre spirits due to his lack of progress in his logical work.

Monk writes that Ludwig Wittgenstein lived and breathed logic, and a temporary lack of inspiration plunged him into despair.

Ludwig Wittgenstein told of his work in logic affecting his mental status in an extreme way.

Ludwig Wittgenstein told Russell on an occasion in Russell's rooms that he was worried about logic and his sins;, once upon arriving in Russell's rooms one night, Wittgenstein announced to Russell that he would kill himself once he left.

Ludwig Wittgenstein is generally believed to have fallen in love with at least three men, and had a relationship with the latter two: David Hume Pinsent in 1912, Francis Skinner in 1930, and Ben Richards in the late 1940s.

Ludwig Wittgenstein later claimed that, as a teenager in Vienna, he had had an affair with a woman.

Additionally, in the 1920s Ludwig Wittgenstein fell in love with a young Swiss woman, Marguerite Respinger, sculpting a bust modelled on her and seriously considering marriage, albeit on condition that they would not have children; she decided that he was not right for her.

The men worked together on experiments in the psychology laboratory about the role of rhythm in the appreciation of music, and Ludwig Wittgenstein delivered a paper on the subject to the British Psychological Association in Cambridge in 1912.

The immense progress on logic during their stay led Ludwig Wittgenstein to express to Pinsent his notion of leaving Cambridge and returning to Norway to continue his work on logic.

Pinsent writes of Ludwig Wittgenstein being "absolutely sulky and snappish" at times, as well.

Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote in May 1912 that Wittgenstein had just begun to study the history of philosophy:.

Ludwig Wittgenstein donated some of his money, at first anonymously, to Austrian artists and writers, including Rainer Maria Rilke and Georg Trakl.

Trakl requested to meet his benefactor but in 1914 when Ludwig Wittgenstein went to visit, Trakl had killed himself.

Ludwig Wittgenstein came to feel that he could not get to the heart of his most fundamental questions while surrounded by other academics, and so in 1913, he retreated to the village of Skjolden in Norway, where he rented the second floor of a house for the winter.

Ludwig Wittgenstein later saw this as one of the most productive periods of his life, writing Logik, the predecessor of much of the Tractatus.

Ludwig Wittgenstein adored the "quiet seriousness" of the landscape but even Skjolden became too busy for him.

Ludwig Wittgenstein soon designed a small wooden house which was erected on a remote rock overlooking the Eidsvatnet Lake just outside the village.

Ludwig Wittgenstein lived there during various periods until the 1930s, and substantial parts of his works were written there.

The importance Ludwig Wittgenstein placed upon this fundamental problem was so great that he believed if he did not solve it, he had no right or desire to live.

David Edmonds and John Eidinow write that Ludwig Wittgenstein regarded Moore, an internationally known philosopher, as an example of how far someone could get in life with "absolutely no intelligence whatever".

In Norway it was clear that Moore was expected to act as Ludwig Wittgenstein's secretary, taking down his notes, with Ludwig Wittgenstein falling into a rage when Moore got something wrong.

Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote to Moore In July of that year conceding that he had "probably no sufficient reason to write to you as I did" but the two did not speak again until 1929.

Ludwig Wittgenstein served first on a ship and then in an artillery workshop "several miles from the action".

Ludwig Wittgenstein was wounded in an accidental explosion, and hospitalised to Krakow.

Ludwig Wittgenstein was decorated with the Military Merit Medal with Swords on the Ribbon, and was commended by the army for "exceptionally courageous behaviour, calmness, sang-froid, and heroism" that "won the total admiration of the troops".

Ludwig Wittgenstein's notebooks attest to his philosophical and spiritual reflections, and it was during this time that he experienced a kind of religious awakening.

Ludwig Wittgenstein discovered Leo Tolstoy's 1896 The Gospel in Brief at a bookshop in Tarnow, and carried it everywhere, recommending it to anyone in distress, to the point where he became known to his fellow soldiers as "the man with the gospels".

The extent to which The Gospel in Brief influenced Ludwig Wittgenstein can be seen in the Tractatus, in the unique way both books number their sentences.

In 1916 Ludwig Wittgenstein read Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov so often that he knew whole passages of it by heart, particularly the speeches of the elder Zosima, who represented for him a powerful Christian ideal, a holy man "who could see directly into the souls of other people".

Iain King has suggested that Ludwig Wittgenstein's writing changed substantially in 1916 when he started confronting much greater dangers during frontline fighting.

Ludwig Wittgenstein subsequently spent nine months in an Italian prisoner of war camp.

Ludwig Wittgenstein apparently talked incessantly about suicide, terrifying his sisters and brother Paul.

Ludwig Wittgenstein decided to do two things: to enroll in a teacher training college as an elementary school teacher, and to get rid of his fortune.

Ludwig Wittgenstein divided it among his siblings, except for Margarete, insisting that it not be held in trust for him.

In 1920, Ludwig Wittgenstein was given his first job as a primary school teacher in Trattenbach, under his real name, in a remote village of a few hundred people.

Ludwig Wittgenstein did not get on well with the other teachers; when he found his lodgings too noisy, he made a bed for himself in the school kitchen.

Ludwig Wittgenstein was an enthusiastic teacher, offering late-night extra tuition to several of the students, something that did not endear him to the parents, though some of them came to adore him; his sister Hermine occasionally watched him teach and said the students "literally crawled over each other in their desire to be chosen for answers or demonstrations".

Russell had agreed to write an introduction to explain why it was important because it was otherwise unlikely to have been published: it was difficult if not impossible to understand, and Ludwig Wittgenstein was unknown in philosophy.

Ludwig Wittgenstein had lost faith in Russell, finding him glib and his philosophy mechanistic, and felt he had fundamentally misunderstood the Tractatus.

Ludwig Wittgenstein's English was poor at the time, and Ramsey was a teenager who had only recently learned German, so philosophers often prefer to use a 1961 translation by David Pears and Brian McGuinness.

Ludwig Wittgenstein argues that the logical structure of language provides the limits of meaning.

The limits of language, for Ludwig Wittgenstein, are the limits of philosophy.

Ludwig Wittgenstein reported in a letter home that Wittgenstein was living frugally in one tiny whitewashed room that only had space for a bed, a washstand, a small table, and one small hard chair.

Ludwig Wittgenstein was accepting no help even from his family.

Ludwig Wittgenstein is through his school dictionary one of the earliest proponents of a German with more than one standard variety.

Ludwig Wittgenstein was taking a stance for multiple standards, against such an axiom, long before these debates ensued.

Ludwig Wittgenstein was a slow learner, and one day Wittgenstein hit him two or three times on the head, causing him to collapse.

Ludwig Wittgenstein carried him to the headmaster's office, then quickly left the school, bumping into a parent, Herr Piribauer, on the way out.

Piribauer had been sent for by the children when they saw Haidbauer collapse; Ludwig Wittgenstein had previously pulled Piribauer's daughter, Hermine, so hard by the ears that her ears had bled.

Piribauer tried to have Ludwig Wittgenstein arrested, but the village's police station was empty, and when he tried again the next day he was told Ludwig Wittgenstein had disappeared.

On 28 April 1926, Ludwig Wittgenstein handed in his resignation to Wilhelm Kundt, a local school inspector, who tried to persuade him to stay; however, Ludwig Wittgenstein was adamant that his days as a schoolteacher were over.

Ten years later, in 1936, as part of a series of "confessions" he engaged in that year, Ludwig Wittgenstein appeared without warning at the village saying he wanted to confess personally and ask for pardon from the children he had hit.

Ludwig Wittgenstein visited at least four of the children, including Hermine Piribauer, who apparently replied only with a "Ja, ja," though other former students were more hospitable.

The Tractatus was now the subject of much debate among philosophers, and Ludwig Wittgenstein was a figure of increasing international fame.

The fundamental philosophical views of Circle had been established before they met Ludwig Wittgenstein and had their origins in the British empiricists, Ernst Mach, and the logic of Frege and Russell.

Whatever influence Ludwig Wittgenstein did have on the Circle was largely limited to Moritz Schlick and Friedrich Waismann and, even in these cases, had little lasting effect on their positivism.

From 1927 to 1928 Ludwig Wittgenstein met with small groups that included Schlick, almost always Waismann, sometimes Rudolf Carnap, and sometimes Herbert Feigl and his future wife Maria Kesper.

In 1926 Ludwig Wittgenstein was again working as a gardener for a number of months, this time at the monastery of Hutteldorf, where he had inquired about becoming a monk.

In particular, Ludwig Wittgenstein focused on the windows, doors, and radiators, demanding that every detail be exactly as he specified.

Brouwer, Ludwig Wittgenstein remained quite impressed, taking into consideration the possibility of a "return to Philosophy".

At the urging of Ramsey and others, Ludwig Wittgenstein returned to Cambridge in 1929.

From 1936 to 1937, Ludwig Wittgenstein lived again in Norway, where he worked on the Philosophical Investigations.

Ludwig Wittgenstein told no one he was leaving the country, except for Hilde who agreed to follow him.

Ludwig Wittgenstein left so suddenly and quietly that for a time people believed he was the fourth Wittgenstein brother to have committed suicide.

Ludwig Wittgenstein began to investigate acquiring British or Irish citizenship with the help of Keynes, and apparently had to confess to his friends in England that he had earlier misrepresented himself to them as having just one Jewish grandparent, when in fact he had three.

Ludwig Wittgenstein was naturalised as a British subject shortly after on 12 April 1939.

Ludwig Wittgenstein had extreme difficulty in expressing himself and his words were unintelligible to me.

Ludwig Wittgenstein's look was concentrated, he made striking gestures with his hands as if he was discoursing.

Whether lecturing or conversing privately, Ludwig Wittgenstein always spoke emphatically and with a distinctive intonation.

Ludwig Wittgenstein spoke excellent English, with the accent of an educated Englishman, although occasional Germanisms would appear in his constructions.

Ludwig Wittgenstein's words came out, not fluently, but with great force.

Ludwig Wittgenstein's face was remarkably mobile and expressive when he talked.

Ludwig Wittgenstein's eyes were deep and often fierce in their expression.

Ludwig Wittgenstein's gaze was concentrated; his face was alive; his hands made arresting movements; his expression was stern.

Ludwig Wittgenstein gave a series of lectures on mathematics, discussing this and other topics, documented in a book, with some of his lectures and discussions between him and several students, including the young Alan Turing, who described Wittgenstein as "a very peculiar man".

Monk writes that Ludwig Wittgenstein found it intolerable that a war was going on and he was teaching philosophy.

Ludwig Wittgenstein grew angry when any of his students wanted to become professional philosophers.

Ludwig Wittgenstein told Ryle he would die slowly if left at Cambridge, and he would rather die quickly.

Ludwig Wittgenstein started working at Guy's shortly afterwards as a dispensary porter, delivering drugs from the pharmacy to the wards where he apparently advised the patients not to take them.

Ludwig Wittgenstein had developed a friendship with Keith Kirk, a working-class teenage friend of Francis Skinner, the mathematics undergraduate he had had a relationship with until Skinner's death in 1941 from polio.

Kirk and Ludwig Wittgenstein struck up a friendship, with Ludwig Wittgenstein giving him lessons in physics to help him pass a City and Guilds exam.

Ludwig Wittgenstein had only maintained contact with Fouracre, from Guy's hospital, who had joined the army in 1943 after his marriage, only returning in 1947.

Ludwig Wittgenstein maintained frequent correspondence with Fouracre during his time away displaying a desire for Fouracre to return home urgently from the war.

The discussion was on the validity of Descartes' Cogito ergo sum, where Ludwig Wittgenstein ignored the question and applied his own philosophical method.

Ludwig Wittgenstein accepted an invitation from Norman Malcolm, then a professor at Cornell University, to stay with him and his wife for several months in Ithaca, New York.

Ludwig Wittgenstein returned to London, where he was diagnosed with an inoperable prostate cancer, which had spread to his bone marrow.

Ludwig Wittgenstein was given a Catholic burial at Ascension Parish Burial Ground in Cambridge.

Ludwig Wittgenstein has no goal to either support or reject religion; his only interest is to keep discussions, whether religious or not, clear.

Ludwig Wittgenstein was said by some commentators to be agnostic, in a qualified sense.

Ludwig Wittgenstein asks the reader to think of language as a multiplicity of language games within which parts of language develop and function.

Ludwig Wittgenstein describes this metaphysical environment as like being on frictionless ice: where the conditions are apparently perfect for a philosophically and logically perfect language, all philosophical problems can be solved without the muddying effects of everyday contexts; but where, precisely because of the lack of friction, language can in fact do no work at all.

Ludwig Wittgenstein argues that philosophers must leave the frictionless ice and return to the "rough ground" of ordinary language in use.

In 2011, two new boxes of Ludwig Wittgenstein papers, thought to have been lost during the Second World War, were found.

Ludwig Wittgenstein is considered by some to be one of the greatest philosophers of the modern era.

Ludwig Wittgenstein doubted that he would be better understood in the future.

Ludwig Wittgenstein once said that he felt as though he were writing for people who would think in a quite different way, breathe a different air of life, from that of present-day men.

In October 1944, Ludwig Wittgenstein returned to Cambridge around the same time as did Russell, who had been living in the United States for several years.

The earlier Ludwig Wittgenstein, whom I knew intimately, was a man addicted to passionately intense thinking, profoundly aware of difficult problems of which I, like him, felt the importance, and possessed of true philosophical genius.

Saul Kripke's 1982 book Ludwig Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language contends that the central argument of Ludwig Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations is a devastating rule-following paradox that undermines the possibility of ever following rules in our use of language.