1.

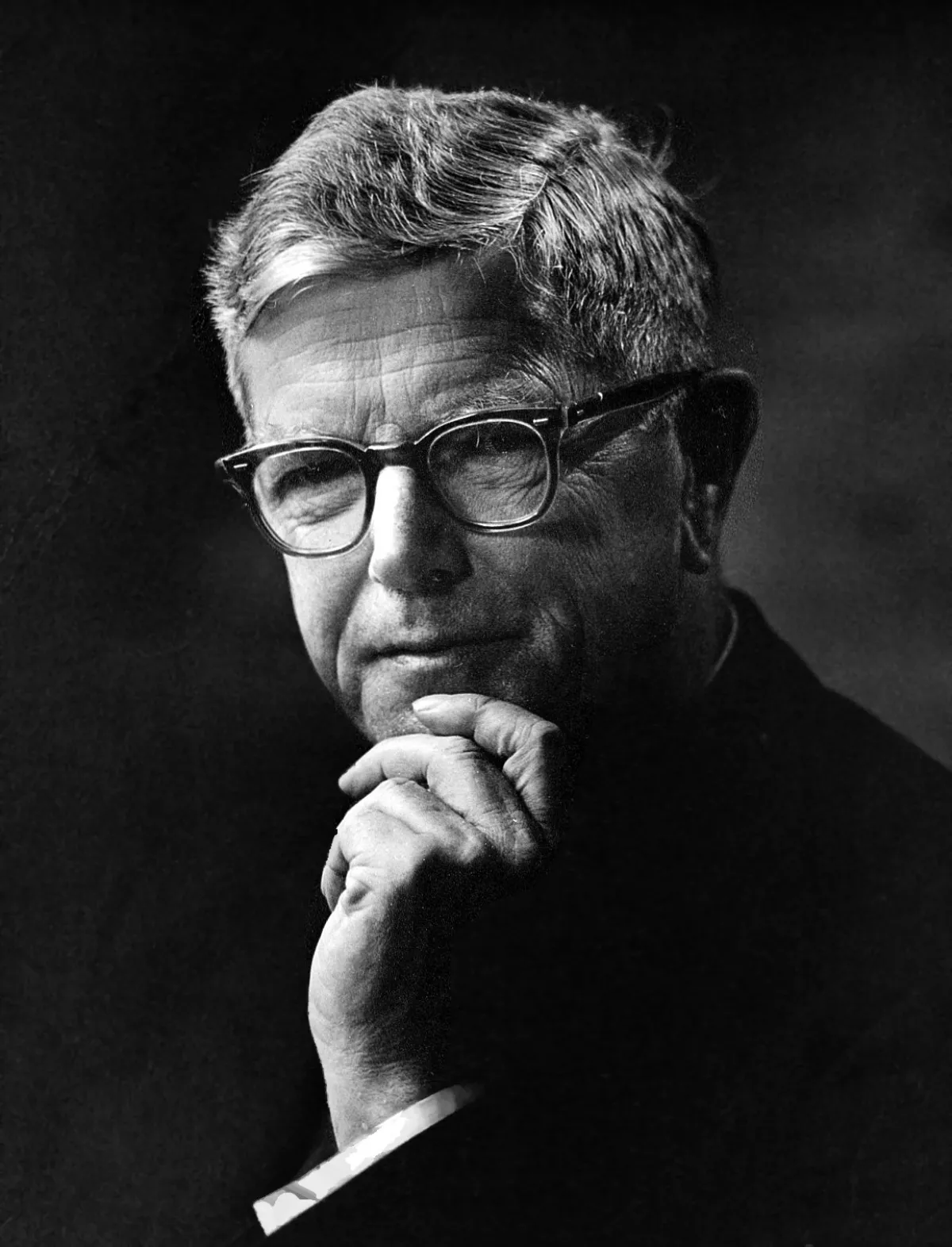

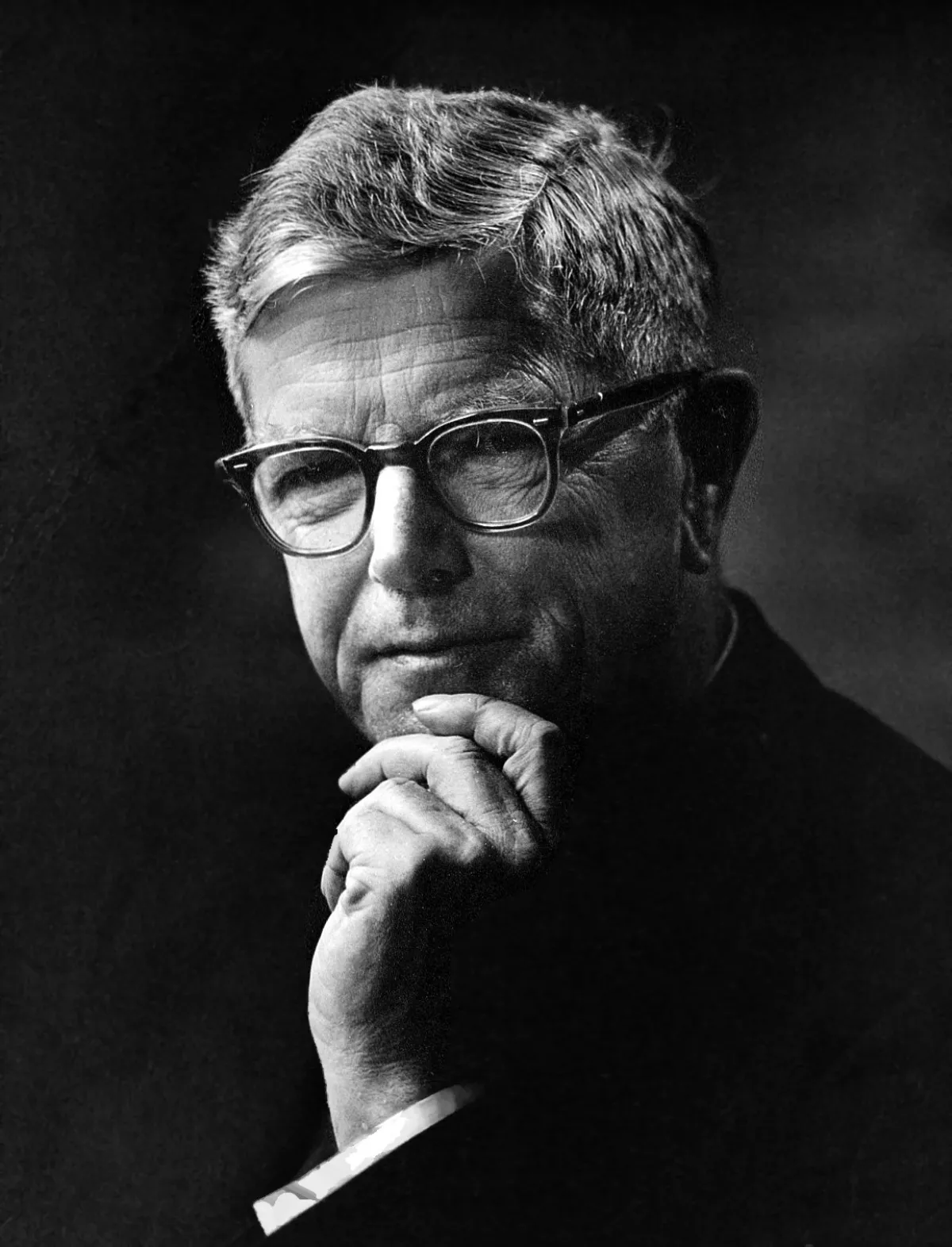

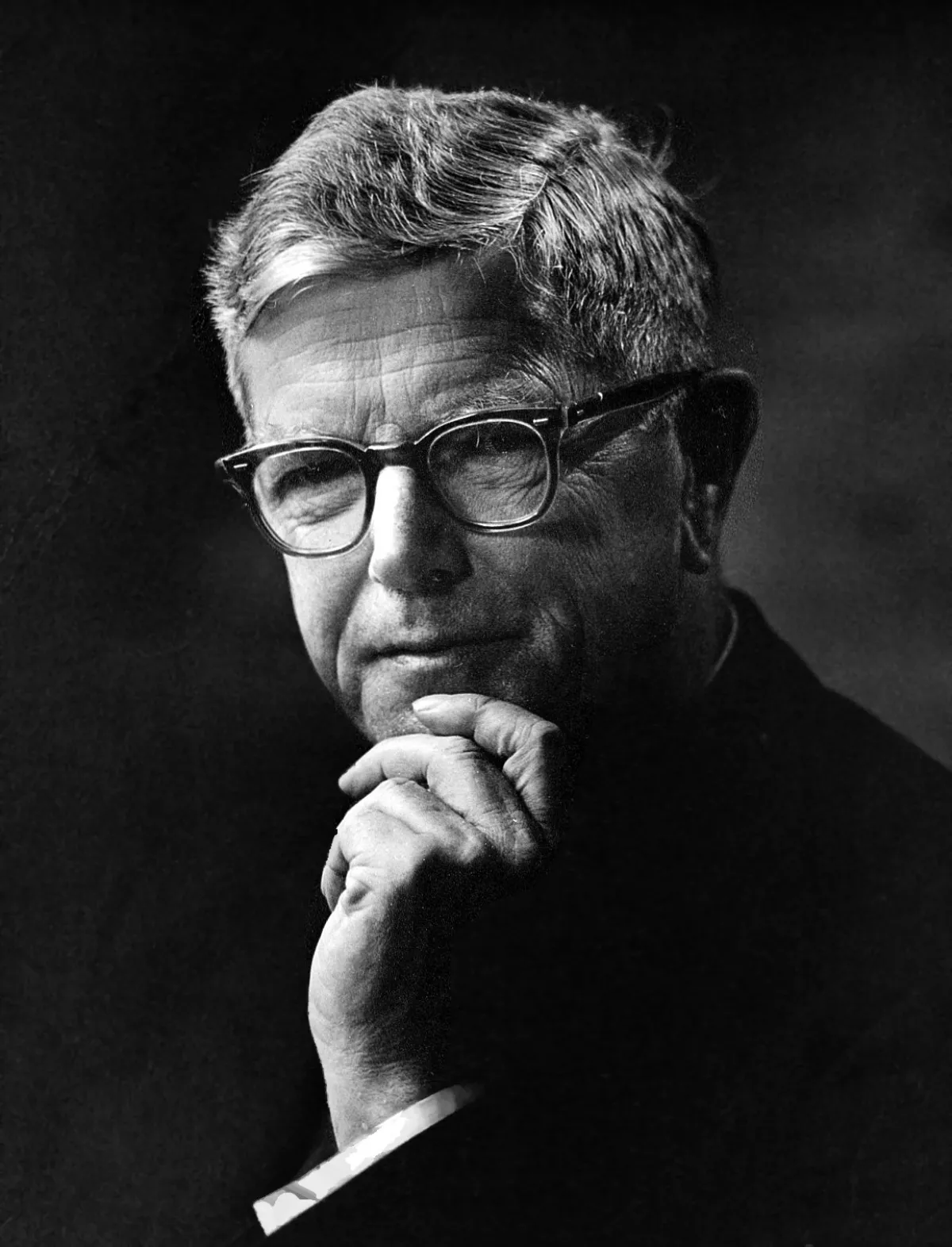

1. Macfarlane Burnet won a Nobel Prize in 1960 for predicting acquired immune tolerance.

1.

1. Macfarlane Burnet won a Nobel Prize in 1960 for predicting acquired immune tolerance.

Macfarlane Burnet went on to conduct pioneering research in microbiology and immunology at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Melbourne, and served as director of the Institute from 1944 to 1965.

From 1965 until his retirement in 1978, Macfarlane Burnet worked at the University of Melbourne.

Macfarlane Burnet was recognised internationally for his achievements: in addition to the Nobel, he received the Lasker Award and the Royal and Copley Medal from the Royal Society, honorary doctorates, and distinguished service honours from the Commonwealth of Nations and Japan.

Macfarlane Burnet was born in Traralgon, Victoria; his father, Frank Macfarlane Burnet, a Scottish emigrant to Australia, was the manager of the Traralgon branch of the Colonial Bank.

Frank Macfarlane Burnet was the second of seven children and from childhood was known as "Mac".

Macfarlane Burnet had an older sister, two younger sisters and three younger brothers.

Macfarlane Burnet first attended a private school run by a single teacher before starting at the government primary school at the age of 7.

Macfarlane Burnet preferred bookish pursuits from a young age and was not enamoured of sport, and by the age of eight was old enough to analyse his father's character; Mac disapproved of Frank and saw him as a hypocrite who espoused moral principles and put on a facade of uprightedness, while associating with businessmen of dubious ethics.

Macfarlane Burnet was interested in the wildlife around the nearby Lake Terang; he joined the Scouts in 1910 and enjoyed all outdoor activities.

Macfarlane Burnet read biology articles in the Chambers's Encyclopaedia, which introduced him to the work of Charles Darwin.

Macfarlane Burnet was educated at Terang State School and attended Sunday school at the local church, where the priest encouraged him to pursue scholastic studies and awarded him a book on ants as a reward for his academic performance.

Macfarlane Burnet advised Frank to invest in Mac's education and he won a full scholarship to board and study at Geelong College, one of Victoria's most exclusive private schools.

Macfarlane Burnet did not enjoy his time there among the scions of the ruling upper class; while most of his peers were brash and sports-oriented, Burnet was bookish and not athletically inclined, and found his fellow students to be arrogant and boorish.

From 1918, Macfarlane Burnet attended the University of Melbourne, where he lived in Ormond College on a residential scholarship.

Macfarlane Burnet enjoyed his time at university and spent much of his free time reading biology books in the library to feed his passion for scientific knowledge.

Macfarlane Burnet had fleeting sporting success, holding down a position in Ormond's First VIII rowing squad for a brief period.

Macfarlane Burnet continued to pursue his study of beetles in private, although his classmates found out and there was no loss in this as they viewed his hobby positively.

Macfarlane Burnet was self-motivated and often skipped lectures to study at his own faster pace and pursue further knowledge in the library, and he came equal first in physics and chemistry in first year.

Macfarlane Burnet began clinical work in the same year, but found it somewhat unpleasant as he was interested in diagnosing the patient and had little interest in showing empathy towards them.

Macfarlane Burnet tried to become involved with communism for a brief period but then resolved to devote himself to scientific research.

The length of time required to study medicine had been reduced to five years to train doctors faster following the outbreak of World War I, and Macfarlane Burnet graduated with a Bachelor of Medicine and a Bachelor of Surgery in 1922, ranking second in the final exams despite the death of his father a few weeks earlier.

Macfarlane Burnet then did a ten-month residency at Melbourne Hospital to gain experience before going into practice.

Macfarlane Burnet enjoyed this period immensely and was disappointed when he had to do his medicine residency.

However, he was engrossed in his work, having been inspired by the neurologist Richard Stawell, whom Macfarlane Burnet came to idolise.

Macfarlane Burnet conducted research into the agglutinin reactions in typhoid fever, leading to his first scientific publications.

Macfarlane Burnet decided to work full-time on the antibody response in typhoid, even though he was technically supposed to pursuing pathology as part of his obligations to the hospital.

Macfarlane Burnet came first in the Doctor of Medicine exams by a long distance, and his score was excluded from the scaling process so that the other students would not fail for being so far behind.

Macfarlane Burnet hoped to raise the standards to make the Institute comparable to the world-class operations in Europe and America.

Kellaway took a liking to Macfarlane Burnet and saw him as the best young talent in the Institute with the ability to help raise it to world leading standards.

Macfarlane Burnet left Australia for England in 1925 and served as ship's surgeon during his journey in exchange for a free fare.

Macfarlane Burnet prepared or maintained bacteria cultures for other researchers in the morning and was free to do his own experiments in the afternoon.

Macfarlane Burnet was awarded the Beit Memorial Fellowship by the Lister Institute in 1926; this gave him enough money for him to resign his curator position and he began full-time research on bacteriophages.

Macfarlane Burnet injected mice with bacteriophage and observed their immunological reactions and believed bacteriophages to be viruses.

Macfarlane Burnet was given an invitation to deliver a paper at the Royal Society of Medicine in 1927 on the link between O-agglutinins and bacteriophage.

Macfarlane Burnet began attending the Fabian Society functions and befriended some communists, although he refrained from joining them in overt left-wing activism.

Macfarlane Burnet spent his free time enjoying theatre, engaging in amateur archaeology and cycling through continental Europe.

Macfarlane Burnet was a secondary school teacher and daughter of a barrister's clerk and the pair had met in 1923 and had a few dates but did not keep in touch.

When Macfarlane Burnet returned to Australia, he went back to the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, where he was appointed assistant director by Kellaway.

Macfarlane Burnet identified Staphylococcus aureus in the toxin-antitoxin mixture that had been administered to the children; it had been picked up from the skin of one of the children and then transmitted to the others in the injections.

Between 1932 and 1933, Macfarlane Burnet took leave of absence to undertake a fellowship at the National Institute for Medical Research in London.

The Great Depression had resulted in Macfarlane Burnet's salary being cut from 1000 to 750 pounds, and the National Institute had been given a large grant from the Rockefeller Foundation that allowed them to hire Macfarlane Burnet at 1000 pounds per annum.

Macfarlane Burnet brought back a set of viruses from the National Institute to begin the basis of research in Melbourne.

When Macfarlane Burnet returned to Australia, he continued his work on virology, including the epidemiology of herpes simplex.

Macfarlane Burnet was involved in two projects that were not viral, the characterisation of the causative agents of psittacosis and Q fever.

Macfarlane Burnet first tested the vaccine on a group of medical students, and after a promising test on 107 army volunteers in February 1942 following a rise in infections, a large-scale program was introduced two months later to inoculate all new recruits after an influenza A outbreak.

Macfarlane Burnet had similar doubts, particularly given his taciturn nature, but applied for the position anyway.

Unlike his predecessor, who valued a broad gamut of research activities, Macfarlane Burnet was of the opinion that the Institute could not make a significant impact at global level in this way, and he pursued a policy of focusing all effort into one area at a time.

In 1944, it was decided by the University of Melbourne that Macfarlane Burnet would be appointed a professor as part of a cooperative program so that university students could be experimentally trained at the Institute, while the researchers engaged in some teaching.

Macfarlane Burnet was not interested in the politics of university funding, and his disengagement from administrative matters engendered resentment.

Macfarlane Burnet made significant contributions to influenza research; he developed techniques to grow and study the virus, including hemagglutination assays.

Macfarlane Burnet worked on a live vaccine against influenza, but the vaccine was unsuccessful when tested during World War II.

Between 1951 and 1956, Macfarlane Burnet worked on the genetics of influenza.

Macfarlane Burnet examined the genetic control of virulence and demonstrated that the virus recombined at high frequency; this observation was not fully appreciated until several years later, when the segmented genome of influenza was demonstrated.

In 1957, Macfarlane Burnet decided that research at the Institute should focus on immunology.

Macfarlane Burnet reached the decision unilaterally, leaving many of the research staff disillusioned and feeling the action was arrogant; for Macfarlane Burnet's part he was comfortable with the decision as he thought it to be effective.

Macfarlane Burnet was suspicious of the direction in which immunology was headed, and the increasing emphasis on technology and more intricate experiments, and colleagues felt that Macfarlane Burnet's conservative attitude was a factor in his decision to turn the Institute's focus to immunology.

Macfarlane Burnet began to switch his focus to immunology in the 1940s.

Macfarlane Burnet regarded the "self" of the host body as being actively defined during its embryogenesis through complex interactions between immune cells and all the other cells and molecules within an embryo.

Macfarlane Burnet and Medawar were able to coordinate their work effectively despite their rather different personalities and physical separation; Macfarlane Burnet was taciturn whereas Medawar was a young and urbane Englishman, but they greatly respected one another.

Macfarlane Burnet noted that his contributions to immune tolerance were strictly theoretical:.

Macfarlane Burnet was interested in how the body produces antibodies in response to antigens.

Macfarlane Burnet was not satisfied with this explanation, and in the second edition of "The Production of Antibodies", he and Fenner advanced an indirect template theory which proposed that each antigen could influence the genome, thus effecting the production of antibodies.

Macfarlane Burnet developed a model which he named clonal selection that expanded on and improved Jerne's hypothesis.

Macfarlane Burnet proposed that each lymphocyte bears on its surface specific immunoglobulins reflecting the specificity of the antibody that will later be synthesised once the cell is activated by an antigen.

Macfarlane Burnet wrote further about the theory in his 1959 book The Clonal Selection Theory of Acquired Immunity.

Macfarlane Burnet's theory predicted almost all of the key features of the immune system as we understand it today, including autoimmune disease, immune tolerance and somatic hypermutation as a mechanism in antibody production.

The clonal selection theory became one of the central concepts of immunology, and Macfarlane Burnet regarded his contributions to the theoretical understanding of the immune system as his greatest contribution to science, writing that he and Jerne should have received the Nobel for this work.

Some commentators argue he published in an Australian journal to fast-track his hypothesis and obtain priority for his theory over ideas that were published later that year in a paper written by David Talmage, which Macfarlane Burnet had read prior to its publication.

In 1960, Macfarlane Burnet scaled back his laboratory work, taking one day off per week to concentrate on writing.

Macfarlane Burnet oversaw an expansion of the Hall Institute and secured funding from the Nuffield Foundation and the state government to build two further floors in the building and take over some of the space taken up by the pathology department at the Royal Melbourne Hospital.

Macfarlane Burnet determined the policies himself, and personally selected all of the research staff and students, relying on a small staff to enforce his plans.

Macfarlane Burnet continued to be active in the laboratory until his retirement in 1965, although his experimental time began to decrease as the operations became increasingly focused on immunology; Burnet's work in this area had been mostly theoretical.

From 1937 Macfarlane Burnet was involved in a variety of scientific and public policy bodies, starting with a position on a government advisory council on polio.

Macfarlane Burnet recognised the importance of co-operation with the media if the general public was to understand science and scientists, and his writings and lectures played an important part in the formulation of public attitudes and policy in Australia on a variety of biological topics.

Macfarlane Burnet served as a member or chairman of scientific committees, both in Australia and overseas.

Macfarlane Burnet's report was titled War from a Biological Angle.

Internationally, Macfarlane Burnet was a chairman of the Papua New Guinea Medical Research Advisory Committee between 1962 and 1969.

At the time, Papua New Guinea was an Australian territory, and Macfarlane Burnet had first travelled there as his son was posted there.

Macfarlane Burnet was particularly interested in kuru, and lobbied the Australian government to establish the Papua New Guinea Institute of Human Biology.

Macfarlane Burnet later helped oversee the institute's contribution to the Anglo-Australian participation in the International Biological Programme in the Field of Human Adaptability.

Macfarlane Burnet served as first chair for the Commonwealth Foundation, a Commonwealth initiative to foster interaction between the member countries' elite, and he was active in the World Health Organization, serving on the Expert Advisory Panels on Virus Diseases and on Immunology between 1952 and 1969 and the World Health Organization Medical Research Advisory Committee between 1969 and 1973.

Macfarlane Burnet advocated a less hierarchical relationship between a professor and student, something seen as a move away from the English tradition prevalent in Australia towards an American model.

Macfarlane Burnet called for the downgrading of the importance placed on the liberal arts.

Macfarlane Burnet's ideas were too radical for his peers and he stepped down from the role in 1970 after none of his suggestions had made an impact.

Macfarlane Burnet was opposed to the use of nuclear power in Australia owing to the issues of nuclear proliferation.

Macfarlane Burnet later retracted his objections to uranium mining in Australia, feeling that nuclear power was necessary while other renewable energy sources were being developed.

Macfarlane Burnet was a critic of the Vietnam War and called for the creation of an international police force.

Macfarlane Burnet wrote an autobiography entitled Changing Patterns: An Atypical Autobiography, which was released in 1968.

Macfarlane Burnet was known for his ability to write quickly, often without a final draft, and his ability to convey a message to readers from a wide spectrum of backgrounds, but he was himself sceptical that his opinions had much influence.

Macfarlane Burnet continued to maintain an intense and focused work schedule, often shunning others to keep up a heavy writing load.

Macfarlane Burnet became president of the Australian Academy of Science in 1965, having been a foundational fellow when the Academy was formed in 1954.

Macfarlane Burnet helped establish the Academy's Science and Industry Forum, which was formed in the second year of his leadership in order to improve dialogue between researchers and industrialists.

Macfarlane Burnet laid the foundations of the Australian Biological Resources Study.

Macfarlane Burnet saw the Academy as the peak lobby group of the scientific community and their main liaison with government and industry.

Macfarlane Burnet tried to lift its profile and use it to persuade the political and industrial leadership to invest more in science.

Macfarlane Burnet wanted to use the Academy to increase the involvement of the eminent scientists of Australia in training and motivating the next generation, but these initiatives were not successful due to a lack of concrete method.

Macfarlane Burnet wanted to stop the Royal Society from operating in Australia and accepting new Australian members.

Macfarlane Burnet reasoned that the Australian Academy would not be strong if the Royal Society would be able to compete with it, and he felt that if Australian scientists were allowed to possess membership of both bodies, the more established Royal Society would make the Australian Academy look poor in comparison.

In 1966, Macfarlane Burnet accepted a nomination from Australia Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies to become the inaugural chairman of the Commonwealth Foundation, a body that aimed to increase the professional interchange between the various nations of the British Commonwealth.

Macfarlane Burnet served in the role for three years and helped start it on a path of steady growth, although he was unable to use it as a personal platform to espouse the importance of human biology.

Macfarlane Burnet delivered the inaugural Oscar Mendelsohn lecture in 1971 at Monash University and advocated policies for Australia such as population control, prevention of war, long-term plans for the management of the environment and natural resources, Aboriginal land rights, socialism, recycling, advertising bans on socially harmful products, and more regulation of the environment.

Macfarlane Burnet angrily denounced French nuclear testing in the Pacific, and after consistently voting for the ruling Liberal Party coalition as it ruled for the past few decades, signed an open letter backing the opposition Labor Party of Gough Whitlam, which took power in 1972.

Macfarlane Burnet often found himself frustrated with the refusal of politicians to base policy on long-term objectives, such as the sustainability of human life.

Macfarlane Burnet spoke and wrote widely on the topic of human biology after his retirement, aiming to reach all strata of society.

Macfarlane Burnet courted the media as well as the scientific community, often leading to sensationalist or scientifically unrigorous report of his outspoken views.

In 1966 Macfarlane Burnet presented the Boyer Lectures, focusing on human biology.

Macfarlane Burnet provided a conceptual framework for sustainable development; 21 years later the definition provided by the Brundtland Commission was almost identical.

The books discuss aspects of human biology, a topic which Macfarlane Burnet wrote on extensively in his later years.

Macfarlane Burnet then moved into Ormond College for company, and resumed beetle collecting, but for a year after her death, Burnet tried to alleviate his grief by writing mock letters to her once a week.

In 1978 Macfarlane Burnet decided to officially retire; in retirement he wrote two books.

In 1982, Macfarlane Burnet was one of three contributors to Challenge to Australia, writing about genetic issues and their impact on the nation's impact.

Macfarlane Burnet continued to travel and speak, but in the early 1980s, he and his wife became increasingly hampered by illness.

Macfarlane Burnet made plans to resume scientific meetings, but was then taken ill again, with significant pain in his thorax and legs.

Macfarlane Burnet was given a state funeral by the government of Australia; many of his distinguished colleagues from the Hall Institute such as Nossal and Fenner were pall-bearers, and he was buried near his paternal grandparents after a private family service at Tower Hill cemetery in Koroit, near Port Fairy.

Macfarlane Burnet was one of the signatories of the agreement to convene a convention for drafting a world constitution.

Macfarlane Burnet received extensive honours for his contributions to science and public life during his lifetime.

Macfarlane Burnet was knighted in the 1951 New Year Honours, received the Elizabeth II Coronation Medal in 1953, and was elected appointed to the Order of Merit in the 1958 Queen's Birthday Honours.

Macfarlane Burnet received a Gold and Silver Star from the Japanese Order of the Rising Sun in 1961.

Macfarlane Burnet was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 1969 New Year Honours, and received the Elizabeth II Jubilee Medal in 1977.

Macfarlane Burnet was only the fourth person to receive this honour.

Macfarlane Burnet was a fellow or honorary member of 30 international Academies of Sciences and the American Philosophical Society.

Macfarlane Burnet appears on a Dominican stamp that was issued in 1997.