1.

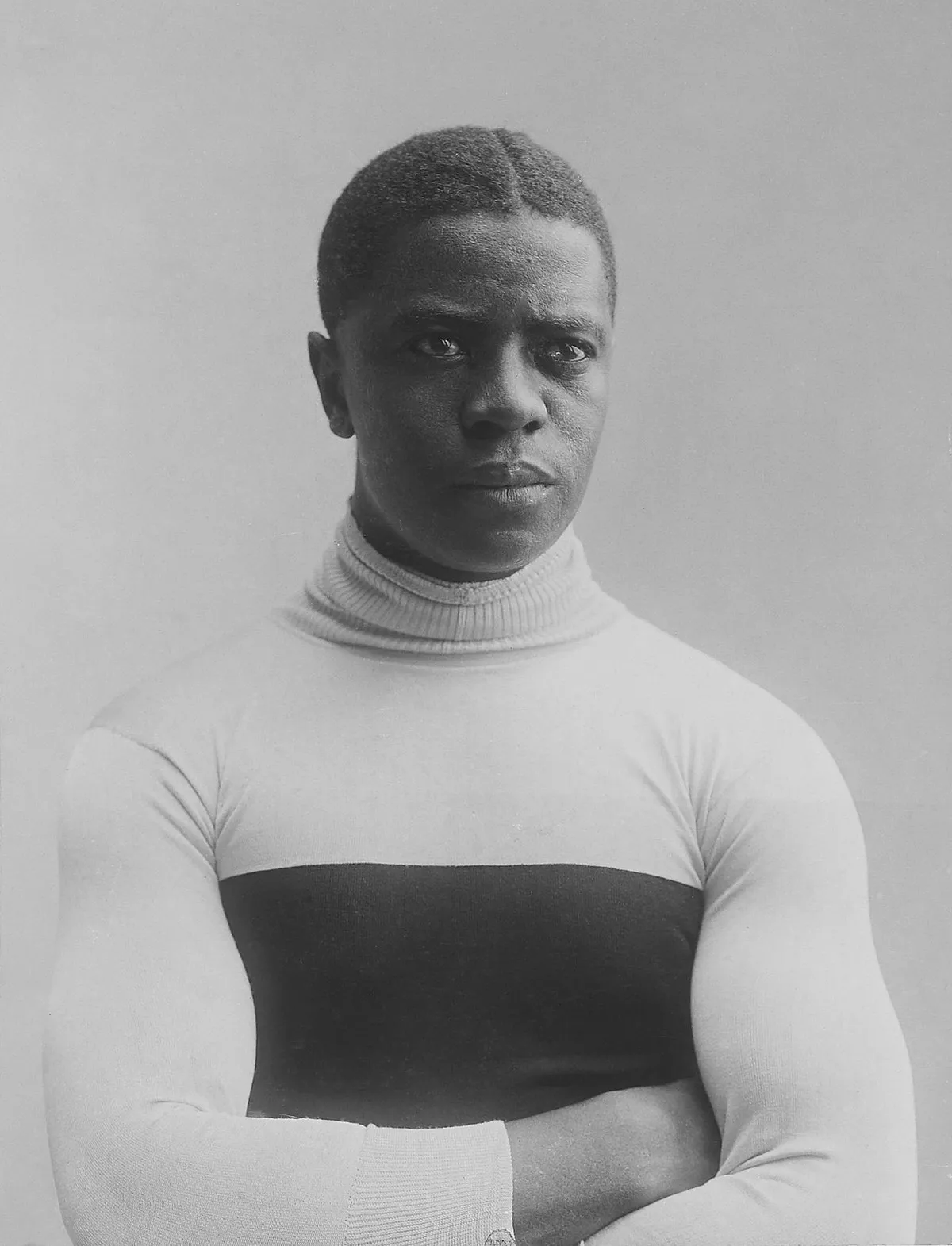

1. Marshall Walter "Major" Taylor was an American professional cyclist.

1.

1. Marshall Walter "Major" Taylor was an American professional cyclist.

Major Taylor was born and raised in Indianapolis, where he worked in bicycle shops and began racing multiple distances in the track and road disciplines of cycling.

Major Taylor moved his focus to the sprint event in 1897, competing in a national racing circuit, winning many races and gaining popularity with the public.

Major Taylor won the 1-mile sprint event at the 1899 world track championships to become the first African American to achieve the level of cycling world champion and the second Black athlete to win a world championship in any sport.

Major Taylor was a national sprint champion in 1899 and 1900.

Major Taylor raced in the US, Europe and Australia from 1901 to 1904, beating the world's best riders.

Towards the end of his life Major Taylor faced severe financial difficulties.

Major Taylor spent the final two years of his life in Chicago, Illinois, where he died of a heart attack in 1932.

Major Taylor has been memorialized in film, music and fashion.

Major Taylor's parents migrated from Louisville, Kentucky, and settled on a farm in Bucktown, Indiana, a rural area on the western edge of Indianapolis.

Major Taylor, born on November 26,1878 in Indianapolis, was one of eight children in the family of five girls and three boys.

When Major Taylor was a child, he occasionally accompanied his father to work and soon became a close friend of the Southards' son, Daniel, who was the same age.

Approximately from the age of 8 until he was about 12, Major Taylor lived with the Southards family and along with Daniel was tutored at their home.

Major Taylor's living arrangement with the Southards provided him with more advantages than his parents could provide; however, this period of his life abruptly ended when the Southards moved to Chicago.

Major Taylor earned $6 a week to clean the shop and perform the stunts, plus a free bicycle worth $35.

The first cycling race Major Taylor won was a ten-mile amateur event in Indianapolis in 1890.

Major Taylor received a 15-minute handicap in the road race because of his young age.

Major Taylor subsequently traveled to Peoria, Illinois, to compete in another meet, finishing in third place in the under-16 age category.

Major Taylor encountered racial prejudice throughout his racing career from some of his competitors.

In 1893, for example, after the 15-year-old Major Taylor beat a one-mile amateur track record, he was "hooted" and then barred from the track.

Major Taylor joined the See-Saw Cycling Club, which was formed by black cyclists of Indianapolis who were unable to join the local all-white Zig-Zag Cycling Club.

Major Taylor won his first significant cycling competition on June 30,1895, when he was the only rider to finish a grueling 75-mile road race near his hometown of Indianapolis.

In 1895, Major Taylor and Munger relocated from Indianapolis to Worcester which, at that time, was a center of the US bicycle industry and included half-a-dozen factories and thirty bicycle shops.

Munger, who was Major Taylor's employer, lifelong friend, and mentor, had decided to move his bicycle manufacturing business to the state of Massachusetts, which was a more tolerant area of the country.

Major Taylor is first mentioned in The New York Times on September 26,1895, as a competitor in the Citizen Handicap event, a ten-mile race on Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn, New York.

Major Taylor raced with a 1:30 handicap in a field of 200 competitors that included nine scratch riders.

In 1896, Major Taylor entered numerous races in the Northeastern states of Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Connecticut.

Major Taylor competed in a half-mile handicap event on an indoor track at New York City's Madison Square Garden II on the opening day of a multi-day event.

Major Taylor won the race riding Munger's "Birdie Special" bicycle and beat Bald by 20 yards in a sprint to the finish.

Madison Square Garden's six-day event in 1896 was the longest race Major Taylor had ever entered.

Major Taylor lived in other eastern cities, such as South Brooklyn, where he once had trained, but it is not known how long he still resided in New York after he became a professional racer.

Early in the season, at the Bostonian Cycle Club's "Blue Ribbon Meet" on May 19,1897, Major Taylor rode a Comet bicycle to win first place in the one-mile open professional race.

Major Taylor beat Eddie Bald in a one-mile race in Reading, Pennsylvania, but finished fourth in the prestigious LAW convention in Philadelphia.

In November and December 1897, when the circuit extended to the racially-segregated South, local race promoters refused to let Major Taylor compete because he was black.

Major Taylor returned to Massachusetts for the remainder of the season and Eddie Bald became the American sprint champion in 1897.

Yet, in the early years of his professional racing career, as he competed in and won more races, Major Taylor's reputation continued to increase.

One bicycle model and iinnovation that company owner Charles Metz developed was nicknamed the "Major Taylor," which featured a drop-down handlebar, a bar extension and a smaller wheel.

Major Taylor was among several top cyclists who could claim the national championship in 1898; however, scoring variations and the formation of a new cycling league that year "clouded" his claim to the title.

Early in the year a group of professional racers that included Major Taylor had left the LAW to join a rival group, the American Racing Cyclists' Union, and its professional racing group, the National Cycling Association.

Major Taylor petitioned the LAW for reinstatement in 1898 and was accepted, but Tom Butler, who had remained a LAW member after the break-up, was declared the League's champion that year.

At the 1899 world championships in Montreal, Canada, Major Taylor won the one-mile sprint, to become the first African American to win a world championship in cycling.

Major Taylor was the second black athlete, after Canadian bantamweight boxer George Dixon of Boston, to win a world championship in any sport.

Major Taylor won the one-mile world championship sprint in a close finish a few feet ahead of Frenchman Courbe d'Outrelon and American Tom Butler.

Major Taylor lost in a preliminary heat at Copenhagen and did not compete in the finals.

Tom Cooper was the NCA champion and Major Taylor was the LAW champion.

Fortunately, the ARCU and the NCA, who had banned Major Taylor from competing in their leagues, readmitted him after payment of a $500 fine.

Major Taylor won the American sprint championship on points in 1900.

Major Taylor beat Tom Cooper, the 1899 NCA champion, in a head-to-head match in a one-mile race at Madison Square Garden in front of 50,000 to 60,000 spectators.

Major Taylor eventually settled in Worcester, where, in 1900, he purchased a home on Hobson Street.

In 1901, Major Taylor made his first trip to Europe, but returned to compete in the US after the conclusion of the European spring racing season.

Major Taylor participated in a European tour in 1902, when he entered 57 races and won 40 of them to defeat the champions of Germany, England, and France.

Major Taylor returned to Europe for the racing season in 1908 and in 1909.

Major Taylor finally broke his long-standing decision to avoid Sunday races in 1909 when he was nearing the end of his racing career.

Major Taylor won the race, but he did not return to Europe for the 1910 season and retired from competitive cycling.

When Major Taylor returned to his home in Worcester at the end of his racing career, his estimated net worth was $75,000 to $100,000.

Major Taylor won his final competition, an "old-timers race" among former professional racers, in New Jersey in September 1917.

Major Taylor asserted in his autobiography that prominent bicycle racers of his era often cooperated to defeat him; the Butler brothers, for example, were accused of so doing in the one-mile world championship race at Montreal in 1899.

At the LAW races in Boston, shortly after Major Taylor had won the world championship, he accused the entire field, that included Tom Cooper and Eddie Bald among others, of fouling him.

Major Taylor further stated in his autobiography that he had been elbowed and "pocketed" by other riders to prevent him from sprinting to the front of the pack, a tactic at which he was so successful.

Becker, who claimed that Major Taylor had crowded him during the race, was temporarily suspended while the incident was investigated.

Major Taylor crashed and lay unconscious on the track before he was taken to a local hospital; he later made a full recovery.

Major Taylor explained that he included details of these incidents in his autobiography, along with his comments about his experiences, to serve as an inspiration for other African American athletes trying to overcome racial prejudice and discriminatory treatment in sports.

Major Taylor cited exhaustion as well as the physical and mental strain caused by the racial prejudice he experienced on and off the track as his reasons for retiring from competitive cycling in 1910.

Major Taylor suffered from persistent ill health in his later years.

Major Taylor spent the final two years of his life in poverty, selling copies of his autobiography to earn a meagre income and residing at YMCA Hotel in Chicago's Bronzeville neighborhood.

In March 1932, Major Taylor suffered a heart attack and was hospitalized in the Provident Hospital.

Major Taylor was initially buried at Mount Glenwood Cemetery in Thornton Township, Cook County, near Chicago, in an unmarked pauper's grave.

Major Taylor was hailed as a sports hero in France and Australia.

Major Taylor, who became a role model for other athletes facing racial prejudice and discrimination, was "the first great black celebrity athlete" and a pioneer in his efforts to challenge segregation in sports.

Major Taylor paved the way for others facing similar circumstances.

Annual events taking place in the velodrome or the wider Indy Cycloplex include the Major Taylor Racing League track series, and from 2015, the Major Taylor Cross Cup second division UCI cyclo-cross event.

Major Taylor was posthumously inducted into the US Bicycling Hall of Fame in 1989.

In 1996 and 1997, Major Taylor was posthumously awarded with the USA Cycling Korbel Lifetime Achievement Award and the Massachusetts Hall of Black Achievement, respectively.

In 1998, in Taylor's adopted hometown of Worcester, MA, where he had lived for 35 years, the Major Taylor Association was formed by locals with the goal of erecting a permanent memorial to Taylor outside the Worcester Public Library and telling his story.

The memorial features a bronze sculpture of Major Taylor surrounded by granite, created by Antonio Tobias Mendez, who was chosen from more than 60 others.

At the grand opening of Worcester's Applebee's restaurant in 2000, Major Taylor was selected as its "hometown hero" and has a display of his memorabilia.

In 2002, the Educational Association of Worcester and the Worcester Public Schools, together with the Major Taylor Association, developed a curriculum guide on Taylor, which has since been expanded and used in schools nationwide.

In 1979, the first of what came to be numerous cycling clubs across the country named in Major Taylor's honor was organized in Columbus, Ohio.

Major Taylor is celebrated along the Alum Creek Greenway Trail in Columbus, Ohio.

The Major directed by Derek Cianfrance, which has cuts in various lengths, features a voiceover from rapper Nas and recreates Taylor racing in an indoor velodrome.

In 2019, two Major Taylor-inspired brand collaborations were released, with part of the proceeds going to the NBC.

Also in 2019, Taylor's name and likeness was licensed to Major Taylor Cycling Wear of Columbus Ohio to manufacture and distribute official sports- and cycling-wear bearing the image of Major Taylor.

Major Taylor's wife, Daisy Victoria Morris, was born on January 28,1876, in Hudson, New York.

Major Taylor married Morris in Ansonia, Connecticut, on March 21,1902.

Major Taylor met her around 1900 when she was living in Worcester, with her aunt and uncle.

Around the same time Major Taylor left Worcester and moved to Chicago; he never saw his wife or daughter again.

Major Taylor died in 2005 at age 101; her survivors include a son, Dallas C Brown Jr.