1.

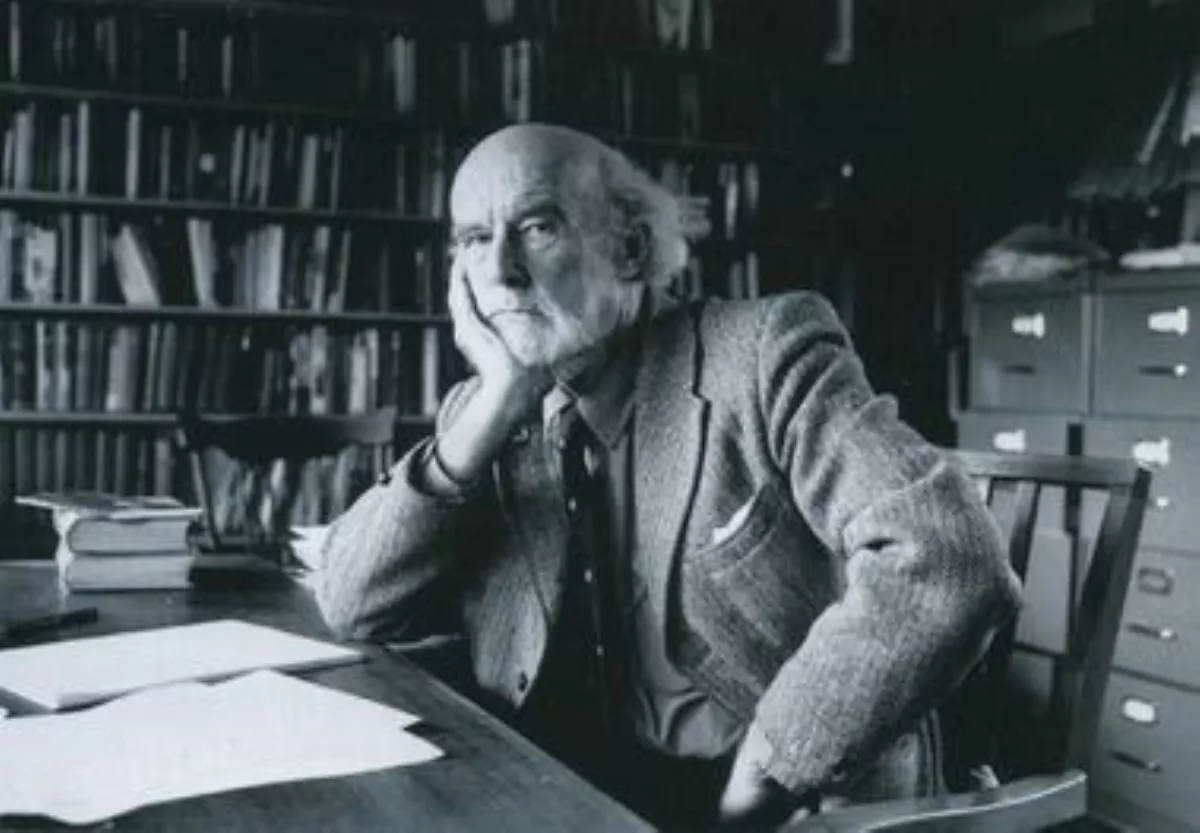

1. Manning Clark has been described as "Australia's most famous historian", but his work has been the target of criticism, particularly from conservatives and classical liberals.

1.

1. Manning Clark has been described as "Australia's most famous historian", but his work has been the target of criticism, particularly from conservatives and classical liberals.

Manning Clark had a difficult relationship with his mother, who never forgot her superior social origins, and came to identify her with the Protestant middle class he so vigorously attacked in his later work.

The family moved to Melbourne when Manning Clark was a child; and lived in what one biographer describes as "genteel poverty" on the modest income of an Anglican vicar.

Manning Clark discovered a love of literature and the classics, and became an outstanding student of Greek, Latin and history.

In terms of his evolving political views, a few years later, around 1944, Manning Clark became a socialist of moderate views, a political position he maintained for the rest of his adult life, with political sympathies broadly placed on the Left and with the Australian Labor Party.

In 1937 Manning Clark won a scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford, and left Australia in August 1938.

Manning Clark began a master of arts thesis on Alexis de Tocqueville.

When World War II broke out in September 1939, Manning Clark was exempted from military service on the grounds of his mild epilepsy.

Manning Clark supported himself while finishing his thesis by teaching history and coaching cricket teams at Blundell's School, a public school at Tiverton in Devonshire, England.

Manning Clark argued that Maurras and other French Catholic intellectuals had been reluctant collaborators, driven to support Vichy out of a dissatisfaction with bourgeois conservatism in France and a fear of the masses propelled by memories of the French Revolution.

Manning Clark offered up what would today be called the Sonderweg interpretation, arguing that in the 19th century the majority of French intellectuals had by and large accepted liberalism, rationalism and the values of liberte, egalite, fraternite whereas the majority of German intellectuals by contrast had embraced conservatism, emotionalism, and a vision of a hierarchical society ruled by an autocratic elite.

Manning Clark noted that at the beginning of the 20th century, the most famous French intellectual was the writer Emile Zola who had been a leading Dreyfusard in the Dreyfus affair as he maintained justice must apply to all French people.

In 1944 Manning Clark returned to Melbourne University to finish his master's thesis, an essential requirement if he was to gain a university post.

Manning Clark supported himself by tutoring politics, and later in the year he was finally appointed to a lectureship in politics.

Manning Clark developed a reputation as a heavy drinker, and was a well-known figure in the pubs of nearby Carlton.

Manning Clark argued it was time for Australian intellectuals to stop treating Great Britain as the model of excellence to which Australians should strive to meet, writing that Australia should be treated as an entity in its own right.

However, Manning Clark himself was critical of "dinkum" Australians, albeit from another direction as he maintained that values such as mateship were mere "comforters" that helped to make life in colonial Australia with its harsh environment more bearable, and failed to provide a means to fundamentally change society.

Manning Clark stated that he did not know what were the new values that Australian society needed, but that historians had the duty to start such a debate.

In 1948 Manning Clark was promoted to Senior Lecturer, and was well set for a lifelong career at Melbourne University.

Manning Clark was not named, but when he went on the radio to defend his colleagues, he was attacked as well.

Thirty of Manning Clark's students signed a letter affirming that he was a "learned and sincere teacher" of "irreproachable loyalty".

The Melbourne University branch of the Communist Party said that Manning Clark was "a reactionary" and no friend of theirs.

In July 1949, Manning Clark moved to Canberra to take up the post of professor of history at the Canberra University College, which was at that time a branch of Melbourne University, and which in 1960 became the School of General Studies of the Australian National University.

Manning Clark lived in Canberra, then still a "bush capital" in a rural setting, for the rest of his life.

From 1949 to 1972 Manning Clark was professor of history, first at CUC and then at ANU.

Manning Clark then held the title emeritus professor until his death.

Manning Clark attacked many of the shibboleths of the nationalist school, such as the idealisation of the convicts, bushrangers and pioneers.

In 1962 Manning Clark contributed an essay to Peter Coleman's book Australian Civilisation, in which he argued that much of Australian history could be seen as a three-sided struggle between Catholicism, Protestantism and secularism, a theme which he continued to develop in his later work.

Manning Clark took leave from Canberra in 1956 and visited Jakarta, Burma and various cities in India, fossicking in museums and archives for documents and maps relating to the discovery of Australia by the Dutch in the 17th century, and the possible discovery of Australia by the Chinese or the Portuguese.

On his return to Australia, Manning Clark began to write The History of Australia, which was originally envisioned as a two-volume work, with the first volume extending to the 1860s and the second volume ending in 1939.

The dominant theme of the early volumes of Manning Clark's history was the interplay between the harsh environment of the Australian continent and the European values of the people who discovered, explored and settled it in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Manning Clark saw Catholicism, Protestantism and the Enlightenment as the three great contending influences in Australian history.

Manning Clark was chiefly interested in colourful, emblematic individuals and the struggles they underwent to maintain their beliefs in Australia; men like William Bligh, William Wentworth, John MacArthur and Daniel Deniehy.

Manning Clark's view was that most of his heroes had a "tragic flaw" that made their struggles ultimately futile.

Manning Clark largely ignored the 20th century historiographic preoccupation with economic and social history, and completely rejected the Marxist stress on class and class struggle as the driving force of social progress.

Manning Clark was not much interested in detailed factual history, and as the History progressed it became less and less based in empirical research and more and more a work of literature: an epic rather than a history.

Manning Clark's colorful writing style with its allusions to the Bible, apocalyptic imagery, and a focus on the psychological struggles within individuals was often criticised by historians, but made him popular with the public.

Ellis, who had a history of personal hostility with Manning Clark, was the first of many critics who took Manning Clark to task for too much speculation about what was in the hearts of men and too little description of what they actually did.

In 1958, Manning Clark visited the Soviet Union for three weeks as a guest of the Soviet Union of Writers, accompanied by the Communist writer Judah Waten and the Queensland poet James Devaney, a Catholic of moderate views.

The delegation visited Moscow and Leningrad, and Manning Clark visited Prague on his way home.

Whatever his real views, Manning Clark enjoyed praise and celebrity, and since he was now getting it mainly from the left he tended to play to the gallery in his public statements.

Manning Clark visited the Soviet Union again in 1970 and in 1973, and he again expressed his admiration for Lenin as a historical figure.

Manning Clark was torn, he said, between "radicalism and pessimism," a pessimism based on doubts that socialism would really make things any better.

In 1975, the Australian Broadcasting Commission invited Manning Clark to give the 1976 Boyer Lectures, a series of lectures which were broadcast and later published as A Discovery of Australia.

The Boyer lectures allowed Manning Clark to describe many of the core ideas of his published work and indeed his own life in characteristic style.

Manning Clark's next work, In Search of Henry Lawson, was a reworking of an essay which was originally written in 1964 as a chapter for Geoffrey Dutton's pioneering The Literature of Australia.

Predictably, and with more than usual justification, Manning Clark saw Lawson as another of his tragic heroes, and he wrote with a good deal of empathy of Lawson's losing battle with alcoholism: a fate Manning Clark himself had narrowly avoided by giving up drink in the 1960s.

In 1983, Manning Clark was hospitalised for the first time and underwent bypass surgery, and further surgery was needed in 1984.

Always a pessimist, Manning Clark became convinced that his time was running out, and from this point he lost interest in the outside world and its concerns and concentrated solely on finishing the History before his death.

Manning Clark's health improved in 1985 and he was able to travel to China and to the Australian war cemeteries in France.

Manning Clark's purported defection to the left in the 1970s caused fury on the literary and intellectual right, particularly since he was accompanied by several other leading figures including Donald Horne and the novelist Patrick White, whose career has some parallels with Manning Clark's.

Manning Clark was denounced in Quadrant and in the columns of the Murdoch press as the godfather of the "Black armband view of history".

Manning Clark was unfavourably compared with Geoffrey Blainey, Australia's leading "orthodox" historian.

Manning Clark reacted to these attacks in typically contrary style by becoming more outspoken, thus provoking further attacks.

The Marxist Raewyn Connell wrote that Manning Clark had no understanding of the historical process, assuming that things happened by chance or "by an odd irony".

Bill Cope, writing in Labour History, the house-journal of left-wing historians, wrote that Manning Clark had been "left behind, both by the new social movements of the postwar decades and the new histories which have transformed the way we see our past and ourselves".

On 24 August 1996, the attack on Manning Clark's reputation reached a new level with a front-page article by the Rupert Murdoch owned Herald Sun, alleging that Manning Clark was a Soviet spy.

Manning Clark was appointed a Companion of the Order of Australia in 1975.

Manning Clark was a Foundation Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities.

Manning Clark won the Fellowship of Australian Writers' Moomba History Book Award and the Henry Lawson Arts Award in 1969, the Australian Literature Society's gold medal in 1970, The Age Book Prize in 1974 and the New South Wales Premier's Literary Award in 1979.

Manning Clark was awarded honorary doctorates by the Universities of Melbourne, Newcastle and Sydney.

Manning Clark House "provides opportunities for the whole community to debate and discuss contemporary issues and ideas, through a program of conferences, seminars, forums, publishing, and arts and cultural events".

In 1999 Manning Clark House inaugurated an annual Manning Clark Lecture, which is given each year by a distinguished Australian.

Manning Clark House is planning to publish an edition of Clark's letters.

The poster featured Manning Clark, holding a set of his History, in a chorus line of significant Australian characters, flanked by Ned Kelly and Nellie Melba.