1.

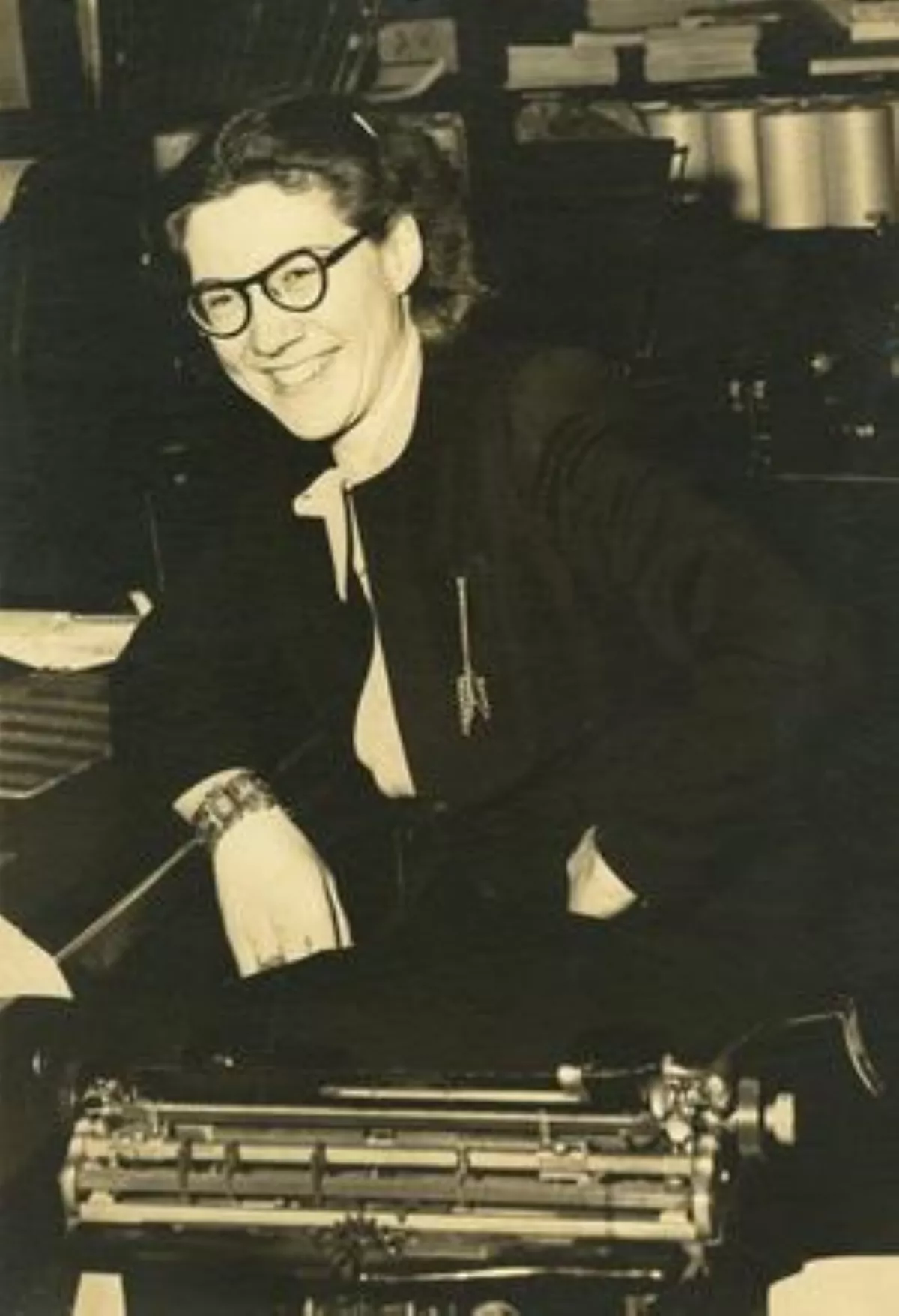

1. Marjorie Paxson was an American newspaper journalist, editor, and publisher during an era in American history when the women's liberation movement was setting milestones by tackling the barriers of discrimination in the media workplace.

1.

1. Marjorie Paxson was an American newspaper journalist, editor, and publisher during an era in American history when the women's liberation movement was setting milestones by tackling the barriers of discrimination in the media workplace.

Marjorie Paxson won the organization's Lifetime Achievement Award and was inducted into its hall of fame.

Marjorie Paxson worked at several different newspapers for different reasons that ranged from being replaced by men returning from the war, to seizing opportunities that afforded her the ability to make positive hard news changes to the women's section.

Marjorie Paxson experienced two demotions as newspapers changed their women's sections into features sections and replaced female editors with male editors.

Marjorie Paxson expressed bitterness over her demotions and attributed them partially to the women's movement.

Marjorie Paxson believed feminist activists unfairly denigrated women's pages and their editors, who she believed had been supporters of the movement.

Marjorie Paxson worked as editor of women's pages in Houston, Miami, Philadelphia; and in Boise, Idaho, as an assistant managing editor.

Marjorie Paxson considered her time there to be the most important work of her career.

Marjorie Paxson helped create the National Women and Media Collection, which documents media coverage of and by women in the United States.

Marjorie Paxson was one of four women's page journalists selected to participate in the Washington Press Foundation's Women in Journalism Oral History Project.

Marjorie Bowers Paxson was born August 13,1923, in Houston, Texas, to Roland B and Marie Margaret Paxson, who had moved to Houston from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where both had grown up.

Marjorie Paxson's father was a petroleum geologist and her mother had attended a secretarial school but discontinued working after she married.

Marjorie Paxson was uninterested in nursing or teaching, then the most common professions open to women, and became involved in journalism while taking a class in high school and writing for her school's newspaper.

Marjorie Paxson's parents aspired to a college education for both their children.

Marjorie Paxson was concerned about whether she would get into Rice, which at the time limited its freshman class to ten percent women.

Marjorie Paxson was admitted and under an endowment attended tuition-free; she recalled her family paying $200 per year for her to attend Rice.

In 1942 Marjorie Paxson transferred to the University of Missouri for her junior year; within a few weeks, most of her male classmates were drafted for World War II.

Marjorie Paxson worked for the university's student newspaper, Columbia Missourian, and graduated from its journalism school in 1944.

Marjorie Paxson credited her work at the Columbia Missourian with helping her get her first job at United Press International wire service.

Marjorie Paxson worked for the AP for two years, then in 1948 moved back to Texas, where she started working in women's pages, which were the only journalism positions open to most women both before and after the war.

Marjorie Paxson was hired in 1948 at age 25 as the society editor for the Houston Post, then considered more progressive than the Houston Chronicle, its primary competitor.

Marjorie Paxson was one of a staff of five in the women's section and earned a salary of $75 per week.

Marjorie Paxson recalled that during this period she had 14 evening dresses, most of them sewn by her mother.

Marjorie Paxson was promoted from society editor to women's page editor in 1951.

Marjorie Paxson attempted to cover hard news but was told by the news editor that he would never allow a news story to be covered in the women's section.

Marjorie Paxson moved pictures of brides off the women's section's front page, where most newspapers always ran them, in favor of issue-oriented stories; she later recalled accomplishing this in late 1951 or early 1952.

Marjorie Paxson considered this one of her major accomplishments at the paper; at one point she had to explain to the paper's de facto publisher, Oveta Culp Hobby, that she would not run a wedding photo of the daughter of one of Hobby's friends on the front of the section.

Marjorie Paxson said that once she had been given the explanation, Hobby backed Marjorie Paxson up.

Marjorie Paxson later recalled the strict order of ranking based on family social prominence used to determine how much column space a wedding announcement was given; the most prominent brides received two columns and the least prominent were covered three in two columns.

In 1952 Marjorie Paxson became women's editor at the Houston Chronicle for $100 a week, but while she supervised a staff of seven, she was not given hiring and firing authority.

Marjorie Paxson was hired as a copy editor in 1956 by Dorothy Jurney, the women's page editor for the Miami Herald, then considered one of the top women's sections in the country.

Marjorie Paxson was mentored in her new position by Jurney and assistant women's editor Marie Anderson and worked alongside Roberta Applegate and Jeanne Voltz.

When Jurney moved to the Detroit Free Press in 1959, Anderson took her place as women's page editor and Marjorie Paxson was promoted to assistant women's editor.

Marjorie Paxson worked at the Herald for 12 years; her ending salary was $9,000 per year.

Marjorie Paxson moved to the St Petersburg Times, known for its progressive content, to become its women's editor in 1968 at a salary of $13,000 per year.

In 1970, following the lead of other major newspapers which were changing their women's sections into features sections, the paper eliminated their women's section, and Marjorie Paxson was demoted to assistant features editor.

Marjorie Paxson was hired as women's page editor by the Philadelphia Bulletin the same year, with a staff of 15.

In 1973 the paper eliminated its women's section in favor of a features section, and Marjorie Paxson was again demoted.

Marjorie Paxson was made associate editor of the paper's Sunday magazine, where her assigned tasks were primarily reading page proofs.

Marjorie Paxson later called it the most important thing she had ever done; it earned her a Headliner Award from the AWC.

Marjorie Paxson viewed this as the writing on the wall and started a job search.

Marjorie Paxson reached out to Neuharth, then the head of Gannett, who had increased the company's focus on promoting women and minorities.

Marjorie Paxson brought her to their headquarters in Rochester for interviews.

Marjorie Paxson then joined Jurney and Jill Ruckelshaus to work on the official report of the third Commission on the Status of Women.

Marjorie Paxson moved to Gannett's Idaho Statesman, a 60,000-circulation paper in Boise, in 1976 to become assistant managing editor.

Marjorie Paxson helped prepare the news room budget and earned the same salary Gannett would have paid a man.

Marjorie Paxson moved to the Public Opinion in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, in 1978 to become the paper's publisher.

Marjorie Paxson was the fourth female publisher of a daily paper in the Gannett media conglomerate.

Marjorie Paxson worked at the Public Opinion for a little under three years and while there accepted a three-week position as associate editor for the daily newspaper of the 1980 United Nations Mid-Decade Conference for Women in Copenhagen.

Marjorie Paxson worked with executive editor John Rowley, whom she described as "display[ing] little understanding of women's issues".

Marjorie Paxson ultimately thought the conference newspaper was demeaning to women, and she wasn't proud of working on it.

In 1980 Marjorie Paxson became publisher of the Muskogee Phoenix in Muskogee, Oklahoma.

Marjorie Paxson held the position of publisher until her retirement in 1986 at the age of 63 after 42 years working in newspapers.

Marjorie Paxson's ending salary was over six figures, including stock options.

Marjorie Paxson was elected president of Theta Sigma Phi in 1963 while working at the Miami Herald and held that office until 1967.

Marjorie Paxson campaigned for a more professional approach, a stance which was not popular with all members, many of whom disagreed with her emphasis on education and training.

Marjorie Paxson led the group to establish a headquarters in Austin, Texas; previously the organization's files had been stored in the national secretary's garage.

Marjorie Paxson lobbied to change the name from the Greek symbols to Women in Communications, which she considered a more businesslike title; the name change ultimately occurred after her time in office ended.

On her first day at the Muskogee Phoenix, Marjorie Paxson was informed by the former publisher that he had had a policy against women wearing pants.

Marjorie Paxson arrived for her second day of work the next morning wearing a pantsuit and walked through the press room, the composing room, and the news room before heading to her office.

Marjorie Paxson then called a meeting of department heads to announce an official change in the dress code.

Marjorie Paxson was angered by what she saw as a betrayal of women's page editors by feminist leaders.

Marjorie Paxson saw these editors as supporters of the movement, as the women's sections had been the only section of most newspapers to provide coverage in the movement's early years; The New York Times placed the 1965 announcement of the formation of the National Organization for Women between an article about Saks Fifth Avenue and a recipe for turkey stuffing.

Marjorie Paxson was twice demoted when her paper replaced its women's section, first at the St Petersburg Times and later at the Philadelphia Bulletin; both times, a man was made editor of the new section.

Marjorie Paxson once described her own firing and demotion to a group of other professional women, one of whom commented, "Marj, you have to accept the fact that you're a casualty of the women's movement", an opinion with which Marjorie Paxson said she agreed.

Marjorie Paxson won a 1969 Penney-Missouri Award, often described as the "Pulitzer Prize of feature writing", for General Excellence at the St Petersburg Times; an AWC Headliner Award for her work on Xilonen in 1975; and an AWC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2001.

Marjorie Paxson was inducted into the association's Hall of Fame in 2003.

Marjorie Paxson donated her papers and $50,000 to the University of Missouri to create the National Women and Media Collection, which documents media coverage by, about and for women in the United States, in 1986, the year of her retirement.

Marjorie Paxson was selected in 1989 to participate in the Washington Press Foundation's Women in Journalism Oral History Project, one of four women's page journalists to be included in a group of over 60 interviewees.