1.

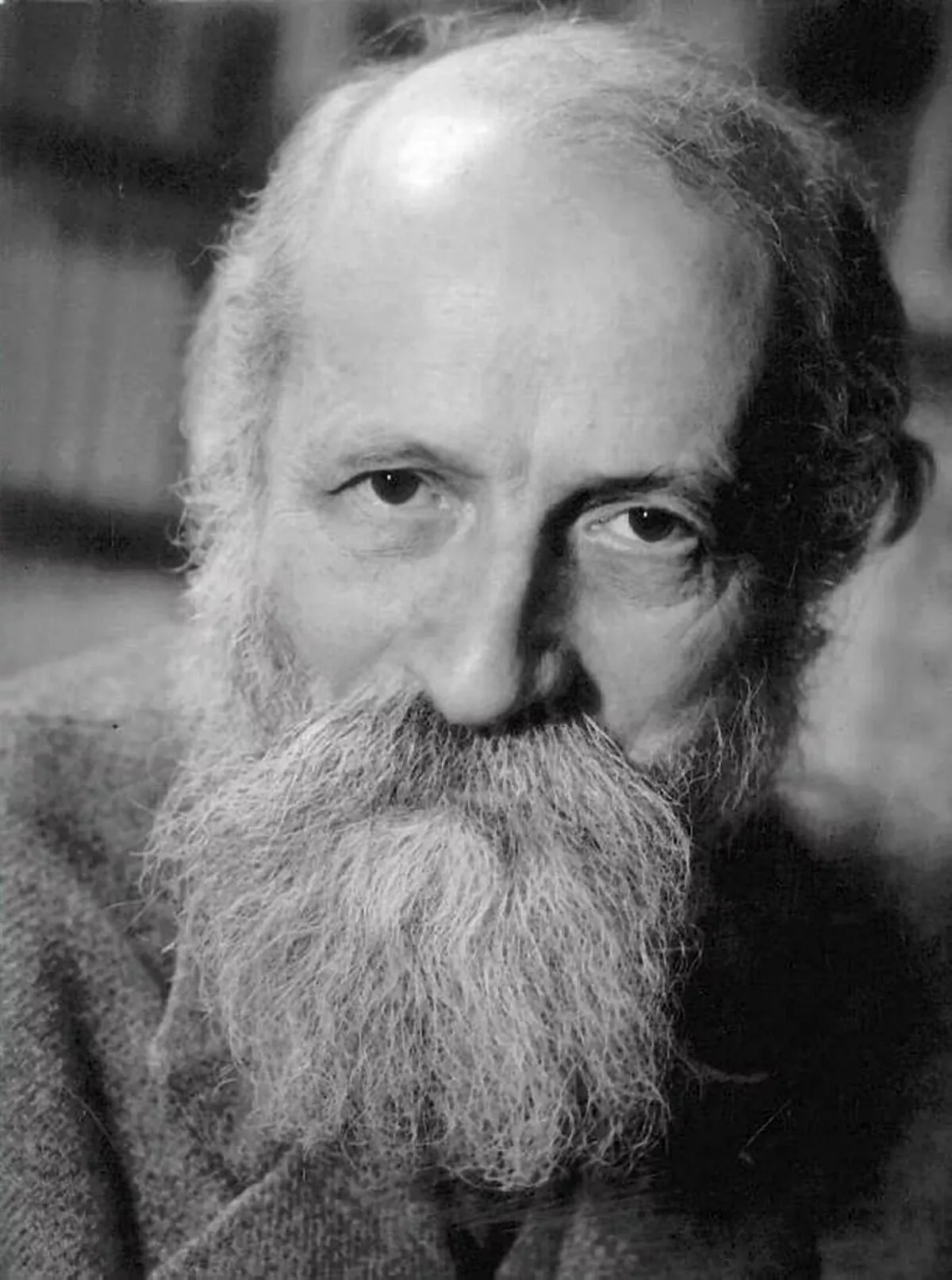

1. Martin Buber produced writings about Zionism and worked with various bodies within the Zionist movement extensively over a nearly 50-year period spanning his time in Europe and the Near East.

1.

1. Martin Buber produced writings about Zionism and worked with various bodies within the Zionist movement extensively over a nearly 50-year period spanning his time in Europe and the Near East.

In 1923, Martin Buber wrote his famous essay on existence, Ich und Du, and in 1925 he began translating the Hebrew Bible into the German language.

Martin Buber was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature ten times, and the Nobel Peace Prize seven times.

Martin Buber was born in Vienna to an Orthodox Jewish family.

Martin Buber's grandfather, Solomon Buber, was a scholar of Midrash and Rabbinic Literature.

In 1892, Martin Buber returned to his father's house in Lemberg.

In 1899, while studying in Zurich, Martin Buber met his future wife, Paula Winkler, a "brilliant Catholic writer from a Bavarian peasant family" who in 1901 left the Catholic Church and in 1907 converted to Judaism.

Martin Buber, initially, supported and celebrated the Great War as a "world historical mission" for Germany along with Jewish intellectuals to civilize the Near East.

In 1930, Martin Buber became an honorary professor at the University of Frankfurt am Main, but resigned from his professorship in protest immediately after Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933.

Martin Buber then founded the Central Office for Jewish Adult Education, which became an increasingly important body as the German government forbade Jews from public education.

In 1938, Martin Buber left Germany and settled in Jerusalem, Mandatory Palestine, receiving a professorship at Hebrew University and lecturing in anthropology and introductory sociology.

Martin Buber was a staunch supporter of a binational solution in Palestine, and, after the establishment of the Jewish state of Israel, of a regional federation of Israel and Arab states.

Martin Buber's influence extends across the humanities, particularly in the fields of social psychology, social philosophy, and religious existentialism.

In contrast, Martin Buber believed the potential of Zionism was for social and spiritual enrichment.

For example, Martin Buber argued that following the formation of the Israeli state, there would need to be reforms to Judaism: "We need someone who would do for Judaism what Pope John XXIII has done for the Catholic Church".

Herzl and Martin Buber would continue, in mutual respect and disagreement, to work towards their respective goals for the rest of their lives.

In 1902, Martin Buber became the editor of the weekly Die Welt, the central organ of the Zionist movement.

Martin Buber admired how the Hasidic communities actualized their religion in daily life and culture.

In stark contrast to the busy Zionist organizations, which were always mulling political concerns, the Hasidim were focused on the values which Martin Buber had long advocated for Zionism to adopt.

Martin Buber produced multiple writings on Zionism and nationalism during this period, expanding upon broader ideas related to Zionism.

In light of the outbreak of WWI, Martin Buber engaged in debates with fellow German philosopher Hermann Cohen in 1915 on the nature of nationalism and Zionism.

Martin Buber continued to explore and develop his views on Zionism in these years.

Martin Buber argued that nationalism is not a natural phenomenon, and that Zionism is a movement centered around religiosity, not nationalism.

Martin Buber rejected the idea of Zionism as just another national movement, and wanted instead to see the creation of an exemplary society; a society which would not be characterized by Jewish domination of the Arabs.

Martin Buber believed that it was necessary for the Zionist movement to reach a consensus with the Arabs even at the cost of the Jews remaining a minority in the country.

Martin Buber evaluated the competing strains of cultural and political Zionism from a somewhat teleological perspective in a 1948 piece "Zionism and Zionism".

Martin Buber was particularly vocal about the treatment of Arab refugees, and was unafraid to criticize top leadership like David Ben-Gurion, the first Prime Minister.

From 1906 until 1914, Martin Buber published editions of Hasidic, mystical, and mythic texts from Jewish and world sources.

In 1921, Martin Buber began his close relationship with Franz Rosenzweig.

In 1923, Martin Buber wrote his famous essay on existence, Ich und Du.

Martin Buber himself called this translation Verdeutschung, since it does not always use literary German language, but instead attempts to find new dynamic equivalent phrasing to respect the multivalent Hebrew original.

Between 1926 and 1930, Martin Buber co-edited the quarterly Die Kreatur.

In 1930, Martin Buber became an honorary professor at the University of Frankfurt am Main.

Martin Buber resigned in protest from his professorship immediately after Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933.

Martin Buber then founded the Central Office for Jewish Adult Education, which became an increasingly important body, as the German government forbade Jews to attend public education.

Finally, in 1938, Martin Buber left Germany, and settled in Jerusalem, then capital of Mandate Palestine.

Martin Buber received a professorship at Hebrew University, there lecturing in anthropology and introductory sociology.

Martin Buber became a member of the group Ihud, which aimed at a bi-national state for Arabs and Jews in Palestine.

Martin Buber is famous for his thesis of dialogical existence, as he described in the book I and Thou.

Martin Buber rejected the label of "philosopher" or "theologian", claiming he was not interested in ideas, only personal experience, and could not discuss God, but only relationships to God.

In I and Thou, Martin Buber introduced his thesis on human existence.

Martin Buber explained this philosophy using the word pairs of Ich-Du and Ich-Es to categorize the modes of consciousness, interaction, and being through which an individual engages with other individuals, inanimate objects, and all reality in general.

The generic motif Martin Buber employs to describe the dual modes of being is one of dialogue and monologue.

Martin Buber argued that this paradigm devalued not only existents, but the meaning of all existence.

Martin Buber was a sort of mentor figure in the lives of Gershom Scholem and Walter Benjamin, the 'Kabbalist of the Holy City' and the 'Marxist Rabbi' of Berlin during the era leading up to, overlapping with proceeding after the Holocaust.

Martin Buber was a scholar, interpreter, and translator of Hasidic lore.

The Hasidic ideal, according to Martin Buber, emphasized a life lived in the unconditional presence of God, where there was no distinct separation between daily habits and religious experience.

In 1906, Martin Buber published Die Geschichten des Rabbi Nachman, a collection of the tales of the Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, a renowned Hasidic rebbe, as interpreted and retold in a Neo-Hasidic fashion by Martin Buber.

Two years later, Martin Buber published Die Legende des Baalschem, the founder of Hasidism.