1.

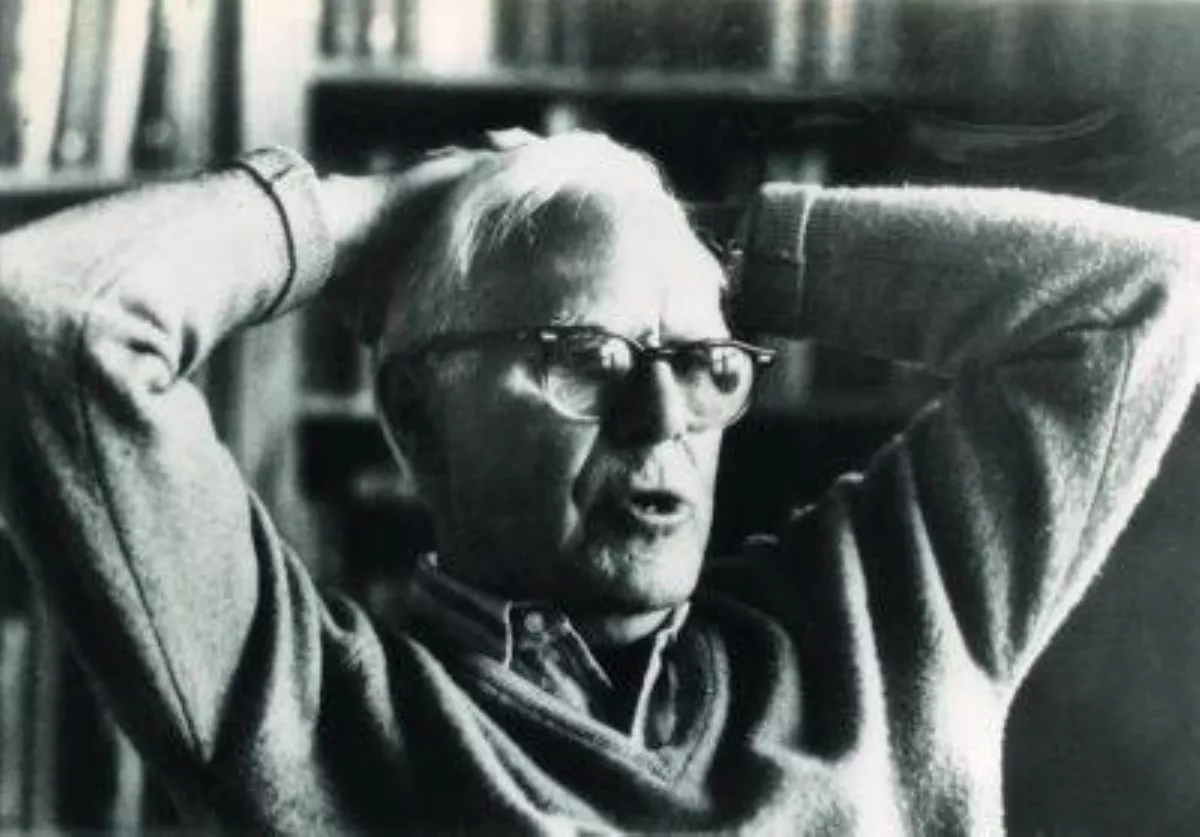

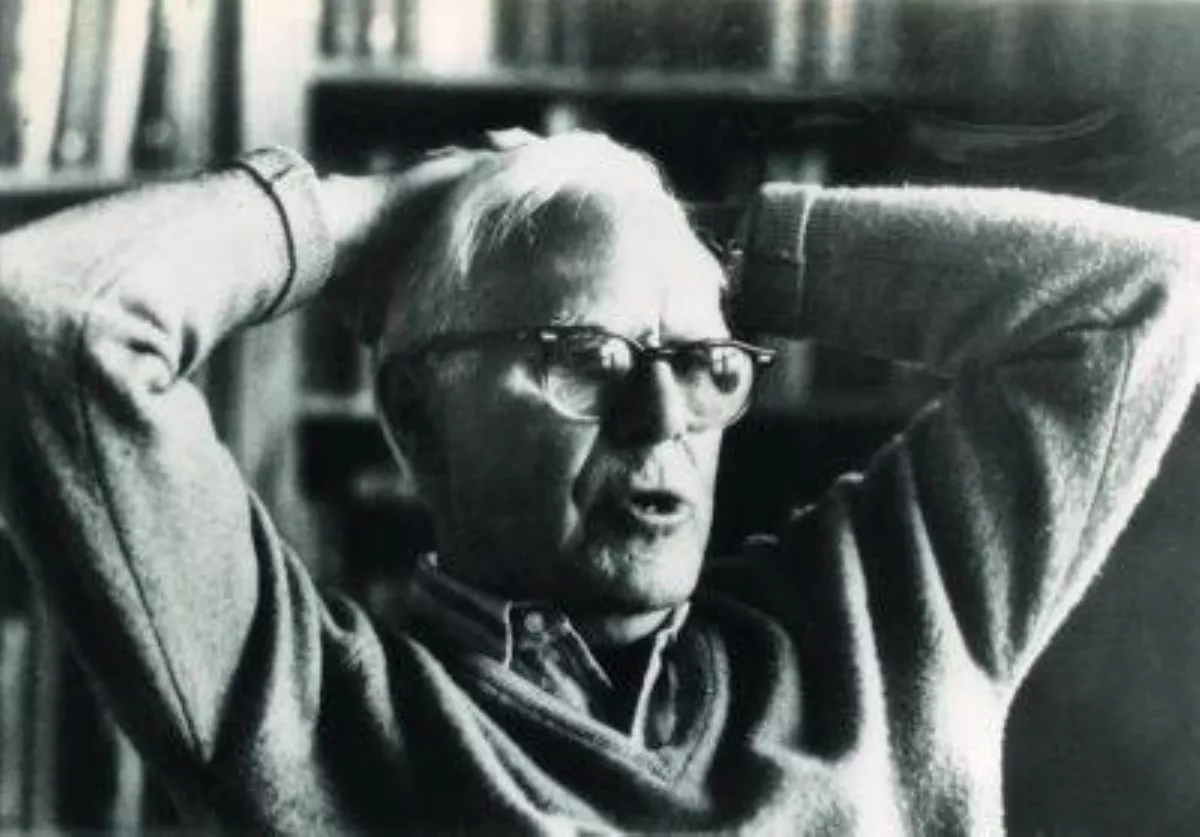

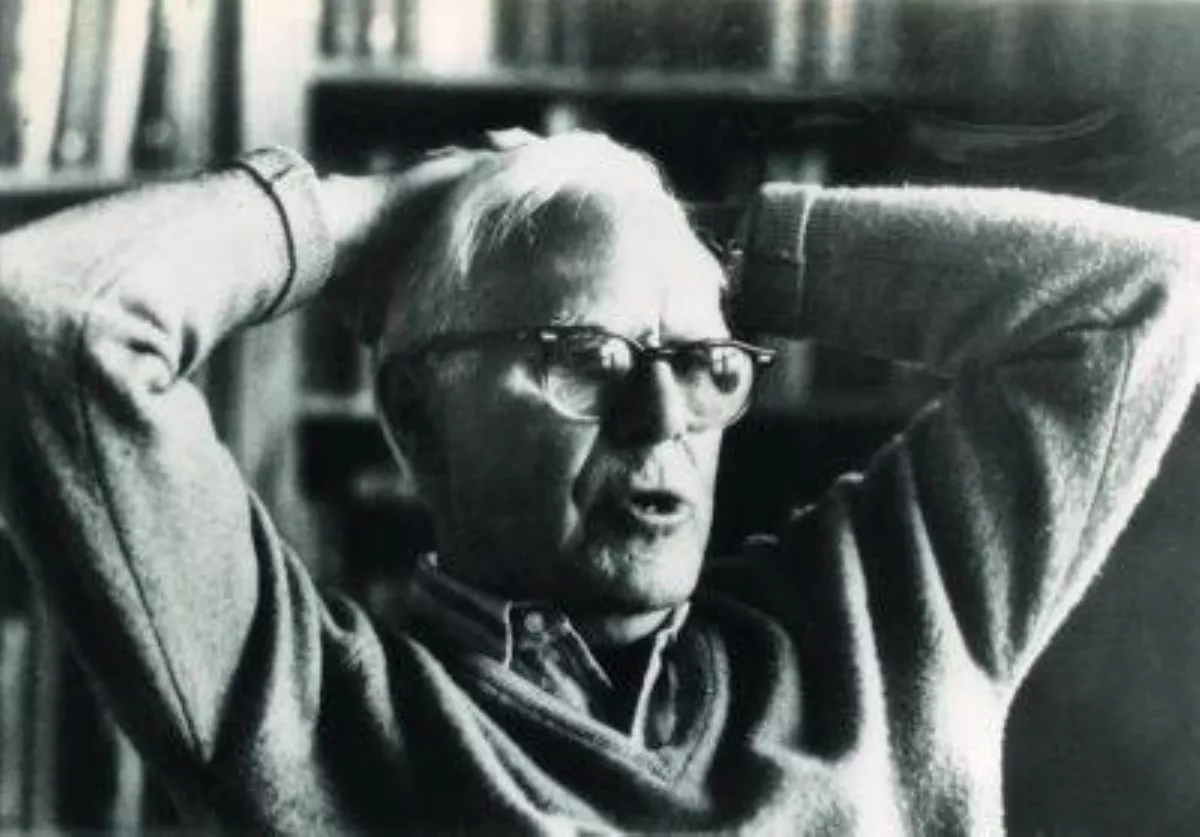

1. Martin Gardner was a leading authority on Lewis Carroll; The Annotated Alice, which incorporated the text of Carroll's two Alice books, was his most successful work and sold over a million copies.

1.

1. Martin Gardner was a leading authority on Lewis Carroll; The Annotated Alice, which incorporated the text of Carroll's two Alice books, was his most successful work and sold over a million copies.

Martin Gardner had a lifelong interest in magic and illusion and in 1999, MAGIC magazine named him as one of the "100 Most Influential Magicians of the Twentieth Century".

Martin Gardner was a prolific and versatile author, publishing more than 100 books.

Martin Gardner was one of the foremost anti-pseudoscience polemicists of the 20th century.

Martin Gardner's 1957 book Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science is a seminal work of the skeptical movement.

Martin Gardner was born into a prosperous family in Tulsa, Oklahoma, to James Henry Gardner, a petroleum geologist, and his wife, Willie Wilkerson Spiers, a Montessori-trained teacher.

Martin Gardner attended the University of Chicago where he studied history, literature and sciences under their intellectually-stimulating Great Books curriculum and earned his bachelor's degree in philosophy in 1936.

Martin Gardner's ship was still in the Atlantic when the war came to an end with the surrender of Japan in August 1945.

Martin Gardner attended graduate school for a year there, but he did not earn an advanced degree.

Martin Gardner's paper-folding puzzles at that magazine led to his first work at Scientific American.

In 1957 Martin Gardner started writing a column for Scientific American called "Mathematical Games".

Martin Gardner continued to write math articles, sending them to The Mathematical Intelligencer, Math Horizons, The College Mathematics Journal, and Scientific American.

Martin Gardner revised some of his older books such as Origami, Eleusis, and the Soma Cube.

Charlotte died in 2000 and in 2004 Martin Gardner returned to Oklahoma, where his son, James Martin Gardner, was a professor of education at the University of Oklahoma in Norman.

Martin Gardner had problems learning calculus and never took a mathematics course after high school.

The subsequent article Martin Gardner wrote on hexaflexagons led directly to the column.

In 1981, on Martin Gardner's retirement from Scientific American, the column was replaced by Douglas Hofstadter's "Metamagical Themas", a name that is an anagram of "Mathematical Games".

Martin Gardner had a major impact on mathematics in the second half of the 20th century.

Martin Gardner's column ran for 25 years and was read avidly by the generation of mathematicians and physicists who grew up in the years 1956 to 1981.

Martin Gardner's writing inspired, directly or indirectly, many who would go on to careers in mathematics, science, and other related endeavors.

Martin Gardner's column introduced the public to books such as A K Dewdney's Planiverse and Douglas Hofstadter's Godel, Escher, Bach.

Martin Gardner's writing was credited as both broad and deep.

Martin Gardner set a new high standard for writing about mathematics.

Martin Gardner had carried on incredibly interesting exchanges with hundreds of mathematicians, as well as with artists and polymaths such as Maurits Escher and Piet Hein.

Martin Gardner maintained an extensive network of experts and amateurs with whom he regularly exchanged information and ideas.

Martin Gardner introduced Conway to Benoit Mandelbrot because he knew of their mutual interest in Penrose tiles.

Martin Gardner's network was responsible for introducing Doris Schattschneider and Marjorie Rice, who worked together to document the newly discovered pentagon tilings.

Martin Gardner prepared each of his columns in a painstaking and scholarly fashion and conducted copious correspondence to be sure that everything was fact-checked for mathematical accuracy.

Communication was often by postcard or telephone and Martin Gardner kept meticulous notes of everything, typically on index cards.

Martin Gardner identified the memorandum that his column was based on and invited readers to write to Rivest to request a copy of it.

Martin Gardner is the single brightest beacon defending rationality and good science against the mysticism and anti-intellectualism that surround us.

Martin Gardner kept up running dialogues with many of them for decades.

Martin Gardner was a critic of self-proclaimed Israeli psychic Uri Geller and wrote two satirical booklets about him in the 1970s using the pen name "Uriah Fuller" in which he explained how such purported psychics do their seemingly impossible feats such as mentally bending spoons and reading minds.

Martin Gardner continued to criticize junk science throughout his life.

Martin Gardner's targets included not just safe subjects like astrology and UFO sightings, but more vigorously defended topics such as chiropractic, vegetarianism, creationism, Scientology, the Laffer Curve, and Christian Science.

Martin Gardner held a lifelong fascination with magic and illusion that began when his father demonstrated a trick to him.

Martin Gardner wrote for a magic magazine in high school and worked in a department store demonstrating magic tricks while he was at the University of Chicago.

Martin Gardner's first published writing was a magic trick in The Sphinx, the official magazine of the Society of American Magicians.

Martin Gardner focused mainly on micromagic and, from the 1930s on, published a significant number of original contributions to this secretive field.

Martin Gardner was well known for his innovative tapping and spelling effects, with and without playing cards, and was most proud of the effect he called the "Wink Change".

Diaconis and Smullyan like Martin Gardner straddled the two worlds of mathematics and magic.

Martin Gardner considered himself a philosophical theist and a fideist.

Martin Gardner believed in a personal God, in an afterlife, and prayer, but rejected established religion.

Martin Gardner described his own belief as philosophical theism inspired by the works of philosopher Miguel de Unamuno.

Martin Gardner has been quoted as saying that he regarded parapsychology and other research into the paranormal as tantamount to "tempting God" and seeking "signs and wonders".

Martin Gardner sometimes attacked prominent religious figures such as Mary Baker Eddy because their claims were unsupportable.

Martin Gardner's annotated version of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, explaining the many mathematical riddles, wordplay, and literary references found in the Alice books, was first published as The Annotated Alice.

The original book arose when Martin Gardner found the Alice books "sort of frightening" when he was young, but found them fascinating as an adult.

Martin Gardner felt that someone ought to annotate them, and suggested to a publisher that Bertrand Russell be asked; when the publisher was unable to get past Russell's secretary, Gardner was asked to take on the project himself.

Martin Gardner was a fan of the Oz books written by L Frank Baum, and in 1988 he published Visitors from Oz, based on the characters in Baum's various Oz books.

Martin Gardner was living in a one-room apartment in Norman, Oklahoma and, as was his custom, wrote it on a typewriter and edited it using scissors and rubber cement.

Martin Gardner took the title from a poem, a so-called grook, by his good friend Piet Hein, which perfectly expresses Gardner's abiding sense of mystery and wonder about existence.

Martin Gardner wrote a "Puzzle Tale" column for Asimov's Science Fiction magazine from 1977 to 1986.

Martin Gardner was a member of the all-male literary banqueting club the Trap Door Spiders, which served as the basis of Isaac Asimov's fictional group of mystery solvers, the Black Widowers.

Martin Gardner's Annotated Casey at the Bat included a parody of the poem, attributed to "Nitram Rendrag".

In later years, Gardner often wrote parodies of his favorite poems under the name "Armand T Ringer", an anagram of his name.

Dr Matrix was not exactly a pen name, although Martin Gardner did pretend that everything in these columns came from the fertile mind of the good doctor.

Martin Gardner maintained that his views are widespread among mathematicians, but Hersh has countered that in his experience as a professional mathematician and speaker, this is not the case.

Martin Gardner recalls how as a young boy a math teacher had scolded him for working on a bit of recreational mathematics and laments at how wrongheaded this attitude is.

Martin Gardner was frustrated by the fact that the history curriculum rarely featured scientists and mathematicians.

Martin Gardner continued to write up until his death in 2010, and his community of fans grew to span several generations.

The attendees at G4G include magicians, mathematicians, jugglers, philosophers, scientific skeptics, fans of Lewis Carroll, puzzle collectors, fans of Conway's game of life, Rubic's cubers, chess masters, and any other topic that Martin Gardner was interested in or had written about.

Martin Gardner was a frequent contributor to The New York Review of Books.