1.

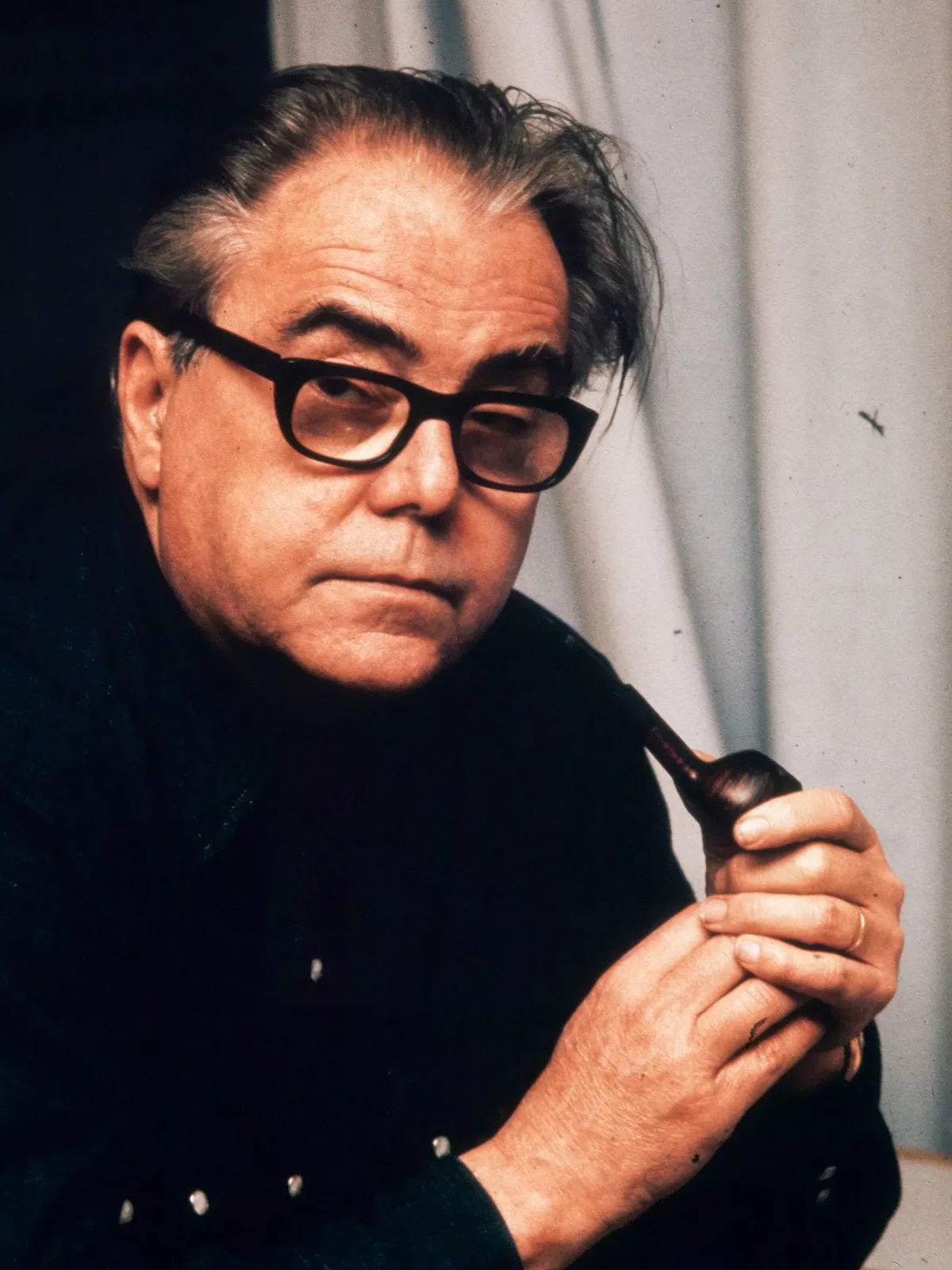

1. Max Frisch was awarded the 1965 Jerusalem Prize, the 1973 Grand Schiller Prize, and the 1986 Neustadt International Prize for Literature.

1.

1. Max Frisch was awarded the 1965 Jerusalem Prize, the 1973 Grand Schiller Prize, and the 1986 Neustadt International Prize for Literature.

Max Rudolf Frisch was born on 15 May 1911 in Zurich, Switzerland, the second son of Franz Bruno Frisch, an architect, and Karolina Bettina Frisch.

Max Frisch had a sister, Emma, his father's daughter by a previous marriage, and a brother, Franz, eight years his senior.

Max Frisch had an emotionally distant relationship with his father, but was close to his mother.

Max Frisch had hoped the university would provide him with the practical underpinnings for a career as a writer, but became convinced that university studies would not provide this.

In 1932, when financial pressures on the family intensified, Max Frisch abandoned his studies.

In 1936 Max Frisch studied architecture at the ETH Zurich and graduated in 1940.

Max Frisch made his first contribution to the newspaper Neue Zurcher Zeitung in May 1931, but the death of his father in March 1932 persuaded him to make a full-time career of journalism in order to generate an income to support his mother.

Max Frisch developed a lifelong ambivalent relationship with the NZZ; his later radicalism was in stark contrast to the conservative views of the newspaper.

Until 1934 Max Frisch combined journalistic work with coursework at the university.

Max Frisch seems to have found many of them excessively introspective even at the time, and tried to distract himself by taking labouring jobs involving physical exertion, including a period in 1932 when he worked on road construction.

Max Frisch kept a diary, later published as Kleines Tagebuch einer deutschen Reise, in which he described and criticised the antisemitism he encountered.

Max Frisch failed to anticipate how Germany's National Socialism would evolve, and his early apolitical novels were published by the Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt without encountering any difficulties from the German censors.

Max Frisch was never tempted to embrace such sympathies, as he explained much later, because of his relationship with Kate Rubensohn, even though the romance itself ended in 1939 after she refused to marry him.

Max Frisch's resolve to disown his second published novel was undermined when it won him the 1938 Conrad Ferdinand Meyer Prize, which included an award of 3,000 Swiss francs.

The book was broadly uncritical of Swiss military life, and of Switzerland's position in war-time Europe, attitudes that Max Frisch revisited and revised in his 1974 Little Service Book ; by 1974 he felt strongly that his country had been too ready to accommodate the interests of Nazi Germany during the war years.

At the ETH, Max Frisch studied architecture with William Dunkel, whose pupils included Justus Dahinden and Alberto Camenzind, later stars of Swiss architecture.

In 1943 Frisch was selected from among 65 applicants to design the new Letzigraben swimming pool in the Zurich district of Albisrieden.

Ferster's house triggered a major court action when it was alleged that Max Frisch had altered the dimensions of the main staircase without reference to his client.

Max Frisch later retaliated by using Ferster as the model for the protagonist in his play The Fire Raisers.

When Max Frisch was managing his own architecture studio, he was generally found in his office only during the mornings.

Max Frisch was already a regular visitor at the Zurich Playhouse while still a student.

In Santa Cruz, his first play, written in 1944 and first performed in 1946, Max Frisch, who had himself been married since 1942, addressed the question of how the dreams and yearnings of the individual could be reconciled with married life.

Max Frisch met the exiled German writer, Carl Zuckmayer, in 1946, and the young Friedrich Durrenmatt in 1947.

An admirer of Brecht's work, Max Frisch now embarked on regular exchanges with the older dramatist on matters of shared artistic interest.

Brecht encouraged Max Frisch to write more plays, while placing emphasis on social responsibility in artistic work.

Max Frisch kept his independent position, by now increasingly marked by scepticism in respect of the polarized political grandstanding which in Europe was a feature of the early Cold War years.

Max Frisch was not alone in quickly deciding that the congress hosts were simply using the event as an elaborate propaganda exercise, and there was hardly any opportunity for the "international participants" to discuss anything.

Max Frisch left before the event ended and headed for Warsaw, notebook in hand, to collect and record his own impressions of what was happening.

Nevertheless, when he returned home the resolutely conservative NZZ concluded that by visiting Poland Max Frisch had simply confirmed his status as a Communist sympathizer, and not for the first time refused to print his rebuttal of their simplistic conclusions.

Max Frisch now served notice on his old newspaper that their collaboration was at an end.

Max Frisch was encouraged by the publisher Peter Suhrkamp to develop the format, and Suhrkamp provided his own feedback and specific suggestions for improvements.

Critical reaction to the new impetus that Max Frisch's Tagebucher was giving to the genre of the "literary diary" was positive: there was a mention of Max Frisch having found a new way to connect with wider trends in European literature.

Sales of these works would nevertheless remain modest until the appearance of a new volume in 1958, by which time Max Frisch had become better known among the general book-buying public on account of his novels.

Max Frisch ends up as the leader of a revolutionary freedom movement, and finds that the power and responsibility that his new position imposes on him leaves him with no more freedom than he had before.

Max Frisch nevertheless regarded Count Oederland as one of his most significant creations: he managed to get it returned to the stage in 1956 and again in 1961, but it failed, on both occasions, to win many new friends.

In 1951, Max Frisch was awarded a travel grant by the Rockefeller Foundation and between April 1951 and May 1952 he visited the United States and Mexico.

The book involves a journey which mirrors a trip that Max Frisch himself undertook to Italy in 1956, and subsequently to America.

The themes of the play seem to have been particularly close to the author's heart: in the space of three years Max Frisch had written no fewer than five versions before, towards the end of 1961, it received its first performance.

Max Frisch had left his wife and children in 1954 and now, in 1959, he was divorced.

Max Frisch was disappointed that his commercially very successful plays Biedermann und die Brandstifter and Andorra had both been, in his view, widely misunderstood.

Max Frisch's answer was to move away from the play as a form of parable, in favour of a new form of expression which he termed "Dramaturgy of Permutation", a form which he had introduced with Gantenbein and which he now progressed with Biographie, written in its original version in 1967.

Max Frisch ended up deciding that he had been expecting more from the audience than he should have expected them to bring to the theatrical experience.

In summer 1962 Max Frisch met Marianne Oellers, a student of Germanistic and Romance studies.

In 1963 they visited the United States for the American premieres of The Fire Raisers and Andorra, and in 1965 they visited Jerusalem where Max Frisch was presented with the Jerusalem Prize for the Freedom of the Individual in Society.

In October 1975, slightly improbably, the Swiss dramatist Max Frisch accompanied Chancellor Schmidt on what for them both was their first visit to China, as part of an official West German delegation.

Two years later, in 1977, Max Frisch found himself accepting an invitation to give a speech at an SPD Party Conference.

In 1978, Frisch survived serious health problems, and the next year was actively involved in setting up the Max Frisch Foundation, established in October 1979, and to which he entrusted the administration of his estate.

In 1980, Max Frisch resumed contact with Alice Locke-Carey and the two of them lived together, alternately in New York City and in Max Frisch's cottage in Berzona, till 1984.

Max Frisch received an honorary doctorate from Bard College in 1980 and another from New York's City University in 1982.

Max Frisch was able, from his own experience of approaching old age, to bring a compelling authenticity to the piece, although he rejected attempts to play up its autobiographical aspects.

In 1984 Max Frisch returned to Zurich, where he would live for the rest of his life.

Max Frisch died on 4 April 1991 while in the middle of preparing for his 80th birthday.

The funeral, which Max Frisch had planned with some care, took place on 9 April 1991 at St Peter's Church in Zurich-Altstadt.

Max Frisch's ashes were later scattered on a fire by his friends at a memorial celebration back in Ticino at a celebration of his friends.

The diaries published by Max Frisch were closer to the literary "structured consciousness" narratives associated with Joyce and Doblin, providing an acceptable alternative but effective method for Max Frisch to communicate real-world truths.

Rolf Keiser points out that when Max Frisch was involved in the publication of his collected works in 1976, the author was keen to ensure that they were sequenced chronologically and not grouped according to genre: in this way the sequencing of the collected works faithfully reflects the chronological nature of a diary.

Max Frisch himself took the view that the diary offered the prose format that corresponded with his natural approach to prose writing, something that he could "no more change than the shape of his nose".

Max Frisch himself is on record with the opinion that the subjective requirements of story telling suited him better than the greater level of objectivity required by theatre work.

All three of the substantive works are autobiographical and all three centre round the dilemma of a young author torn between bourgeois respectability and "artistic" life style, exhibiting on behalf of the protagonists differing outcomes to what Max Frisch saw as his own dilemma.

Characteristic of Max Frisch's stage plays are minimalist stage-sets and the application of devices such as splitting the stage in two parts, use of a "Greek chorus" and characters addressing the audience directly.

Unlike Brecht however, Max Frisch offered few insights or answers, preferring to leave the audience the freedom to provide their own interpretations.

Max Frisch himself acknowledged that the part of writing a new play that most fascinated him was the first draft, when the piece was undefined, and the possibilities for its development were still wide open.

The critic Hellmuth Karasek identified in Max Frisch's plays a mistrust of dramatic structure, apparent from the way in which Don Juan or the Love of Geometry applies theatrical method.

Max Frisch prioritized the unbelievable aspects of theatre and valued transparency.

Unlike his friend, the dramatist Friedrich Durrenmatt, Max Frisch had little appetite for theatrical effects, which might distract from doubts and sceptical insights included in a script.

For Max Frisch, effects came from a character being lost for words, from a moment of silence, or from a misunderstanding.

Max Frisch's style changed across the various phases of his work.

Max Frisch adapted the principles of Bertolt Brecht's Epic theatre both to his dramas and to his prose works.

Notably, in the 1964 novel "Gantenbein", Max Frisch rejected the conventional narrative continuum, presenting instead, within a single novel, a small palette of variations and possibilities.

Already in "Stiller" Max Frisch embedded, in a novel, little sub-narratives in the form of fragmentary episodic sections from his "diaries".

Claus Reschke says that the male protagonists in Max Frisch's work are all similar modern Intellectual types: egocentric, indecisive, uncertain in respect of their own self-image, they often misjudge their actual situation.

Max Frisch's compositions tend to be centred on male protagonists, around which his leading female characters, virtually interchangeable, fulfil a structural and focused function.

In eleven questionnaires Max Frisch asks seemingly innocuous questions on the topics of altruism, marriage, property, women, friendship, money, home, hope, humor, children and death.

Max Frisch's aim is to show, through irony, how one should think correctly.

Max Frisch described himself as a socialist but never joined the political party.

Max Frisch now underwent a rapid transformation, evincing a committed political consciousness.

In 1950 Max Frisch switched publishers again, this time to the arguably more mainstream publishing house then being established in Frankfurt by Peter Suhrkamp.

Max Frisch was still only in his early 30s when he turned to drama, and his stage work found ready acceptance at the Zurich Playhouse, at that time one of Europe's leading theatres, the quality and variety of its work much enhanced by an influx of artistic talent since the mid-1930s from Germany.

Max Frisch's early plays, performed at Zurich, were positively reviewed and won prizes.

The experience encouraged him to pay more attention to audiences outside his native Switzerland, notably in the new and rapidly developing Federal Republic of Germany, where the novel I'm Not Stiller succeeded commercially on a scale that till then had eluded Max Frisch, enabling him now to become a full-time professional writer.

Max Frisch's name is often mentioned along with that of another great writer of his generation, Friedrich Durrenmatt.

The literary journalist Heinz Ludwig Arnold quipped that Durrenmatt, despite all his narrative work, was born to be a dramatist, while Max Frisch, his theatre successes notwithstanding, was born to be a writer of narratives.

Max Frisch found success in his second "homeland of choice", the United States where he lived, off and on, for some time during his later years.

Max Frisch was generally well regarded by the New York literary establishment: one commentator found him commendably free of "European arrogance".

Max Frisch found himself featuring as a "character" in the literature of others.

Max Frisch is himself always at the heart of the matter.

In Durrenmatt's last letter to Max Frisch he coined the formulation that Max Frisch in his work had made "his case to the world".

The film director Alexander J Seiler believes that Frisch had for the most part an "unfortunate relationship" with film, even though his literary style is often reminiscent of cinematic technique.

Seiler explains that Max Frisch's work was often, in the author's own words, looking for ways to highlight the "white space" between the words, which is something that can usually only be achieved using a film-set.

Max Frisch was awarded honorary degrees by the University of Marburg, Germany, in 1962, Bard College, the City University of New York City, the University of Birmingham, and the TU Berlin.

Max Frisch won many important German literature prizes: the Georg Buchner Prize in 1958, the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in 1976, and the Heinrich-Heine-Preis in 1989.

The 100th anniversary of Max Frisch's birth took place in 2011 and was marked by an exhibition in his home city of Zurich.