1.

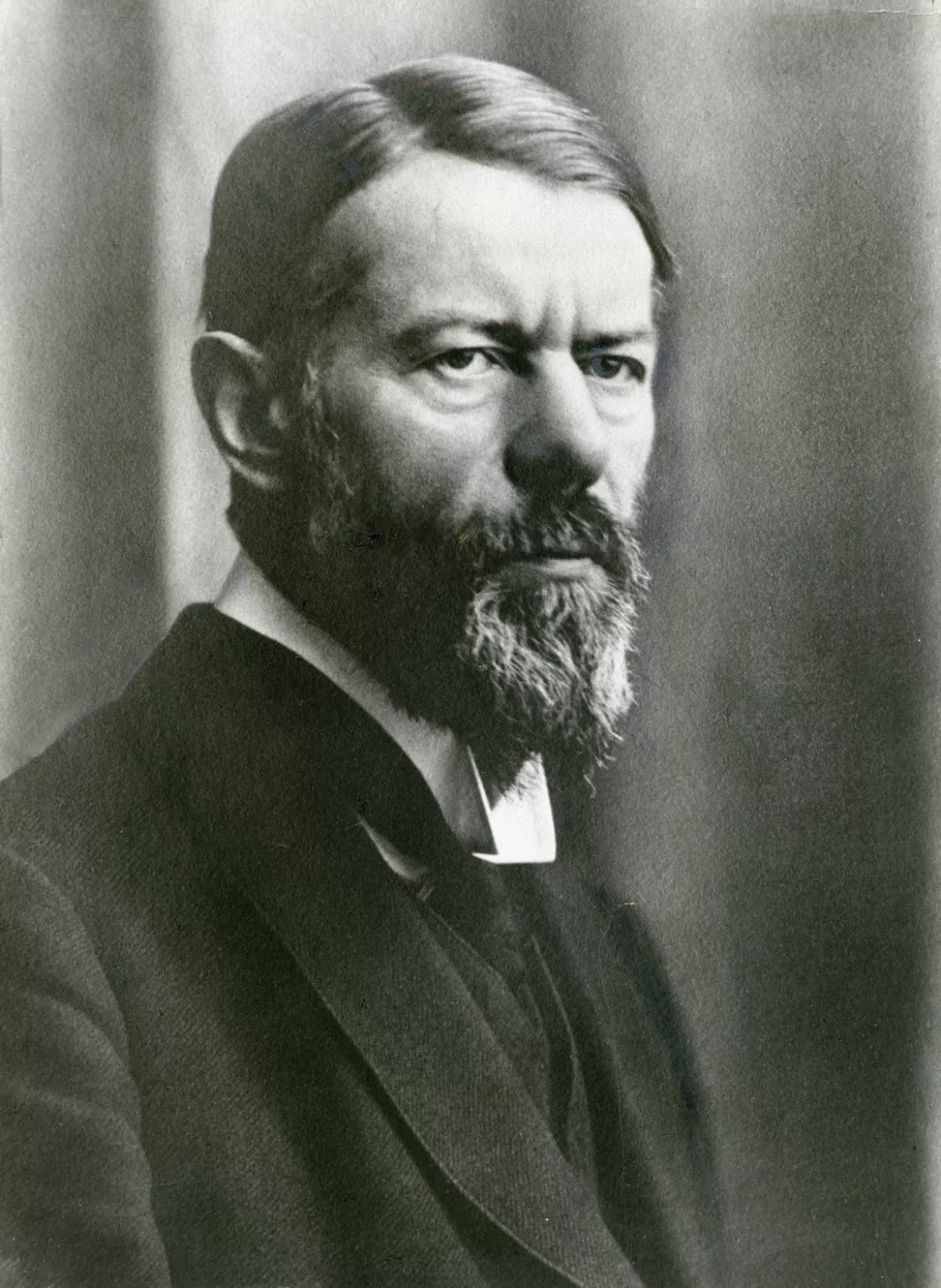

1. Max Weber's ideas continue to influence social theory and research.

1.

1. Max Weber's ideas continue to influence social theory and research.

Max Weber married his cousin Marianne Schnitger two years later.

Max Weber recovered and wrote The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.

Max Weber gave the lectures "Science as a Vocation" and "Politics as a Vocation".

Max Weber died of pneumonia in 1920 at the age of 56, possibly as a result of the post-war Spanish flu pandemic.

Max Weber formulated a thesis arguing that such processes were associated with the rise of capitalism and modernity.

Max Weber argued that the Protestant work ethic influenced the creation of capitalism in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.

In terms of government, Max Weber argued that states were defined by their monopoly on violence and categorised social authority into three distinct forms: charismatic, traditional, and rational-legal.

Max Weber was a key proponent of methodological antipositivism, arguing for the study of social action through interpretive rather than purely empiricist methods.

Max Weber made a variety of other contributions to economic sociology, political sociology, and the sociology of religion.

Maximilian Carl Emil Weber was born on 21 April 1864 in Erfurt, Province of Saxony, Kingdom of Prussia, and his family moved to Berlin in 1869.

Over time, Max Weber was affected by the marital and personality tensions between his father, who enjoyed material pleasures while overlooking religious and philanthropic causes, and his mother, a devout Calvinist and philanthropist.

Max Weber entered the in Charlottenburg in 1870, before attending the between 1872 and 1882.

In 1882, Max Weber enrolled in Heidelberg University as a law student, later studying at the Royal Friedrich Wilhelm University of Berlin and the University of Gottingen.

Max Weber practiced law and worked as a lecturer simultaneously with his studies.

In 1886, Max Weber passed the Referendar examination, which was comparable to the bar association examination in the British and US legal systems.

Under the tutelage of Levin Goldschmidt and Rudolf von Gneist, Max Weber earned his law doctorate in 1889 by writing a dissertation on legal history titled Development of the Principle of Joint Liability and a Separate Fund of the General Partnership out of the Household Communities and Commercial Associations in Italian Cities.

Max Weber befriended Baumgarten and he influenced Max Weber's growing liberalism and criticism of Otto von Bismarck's domination of German politics.

Max Weber was a member of the Burschenschaft Allemannia Heidelberg, a, and heavily drank beer and engaged in academic fencing during his first few years in university.

Max Weber's mother was displeased by his behaviour and slapped him after he came home when his third semester ended in 1883.

However, Max Weber matured, increasingly supported his mother in family arguments, and grew estranged from his father.

From 1887 until her declining mental health caused him to break off their relationship five years later, Max Weber had a relationship and semi-engagement with Emmy Baumgarten, the daughter of Hermann Baumgarten.

Academically, between the completion of his dissertation and habilitation, Max Weber took an interest in contemporary social policy.

Max Weber involved himself in politics, participating in the founding of the left-leaning Evangelical Social Congress in 1890.

Max Weber was put in charge of the study and wrote a large part of the final report, which generated considerable attention and controversy, marking the beginning of his renown as a social scientist.

From 1893 to 1899, Max Weber was a member of the Pan-German League, an organisation that campaigned against the influx of Polish workers.

Max Weber was pessimistic regarding the association's ability to succeed, and it dissolved after winning a single seat in the Reichstag during the 1903 German federal election.

In 1897, Max Weber had a severe quarrel with his father.

Max Weber's condition forced him to seek an exemption from his teaching obligations, which he was granted in 1899.

Max Weber spent time in the in 1898 and in a different sanatorium in Bad Urach in 1900.

Max Weber travelled to Corsica and Italy between 1899 and 1903 in order to alleviate his illness.

Max Weber fully withdrew from teaching in 1903 and did not return to it until 1918.

Max Weber thoroughly described his ordeal with mental illness in a personal chronology that his widow later destroyed.

Max Weber published some of his most seminal works in this journal, including his book The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, which became his most famous work and laid the foundations for his later research on the impact of religion on the development of economic systems.

Max Weber used the trip to learn more about America's social, economic, and theological conditions and how they related to his thesis.

Shortly after returning, Max Weber's attention shifted to the then-recent Russian Revolution of 1905.

Max Weber learned the Russian language in a few months, subscribed to Russian newspapers, and discussed Russian political and social affairs with the Russian community in Heidelberg.

Max Weber was personally popular in that community and twice entertained the idea of a trip to Russia.

Max Weber wrote two essays on it that were published in the.

Max Weber interpreted the revolution as having been the result of the peasants' desire for land.

Max Weber discussed the role of the, rural peasant communities, in Russian political debates.

Max Weber associated the society with the and viewed the two organisations as not having been competitors.

Max Weber unsuccessfully tried to steer the direction of the association.

Max Weber resigned from his position as treasurer in 1912.

Later, during the spring of 1913, Max Weber holidayed in the Monte Verita community in Ascona, Switzerland.

Max Weber opposed Erich Muhsam's involvement because Muhsam was an anarchist.

Max Weber argued that the case needed to be dealt with by bourgeois reformers who were not "derailed".

Max Weber was critical of the anarchist and erotic movements in Ascona, as he viewed their fusion as having been politically absurd.

In time Max Weber became one of the most prominent critics of both German expansionism and the Kaiser's war policies.

Max Weber publicly criticised Germany's potential annexation of Belgium and unrestricted submarine warfare, later supporting calls for constitutional reform, democratisation, and universal suffrage.

Max Weber had previously viewed him negatively but his death made him feel more connected to him.

Max Weber's presence elevated his profile in Germany and served to dispel some of the event's romantic atmosphere.

Max Weber opposed what he saw as the excessive rhetoric of the youth groups and nationalists at Lauenstein, instead supporting German democratisation.

Max Weber began a sadomasochistic affair with Else von Richthofen the next year.

Max Weber was critical of the Treaty of Versailles, which he believed unjustly assigned war guilt to Germany.

In making this case, Max Weber argued that Russia was the only great power that actually desired the war.

Max Weber regarded Germany as not having been culpable for its invasion of Belgium, viewing Belgian neutrality as having obscured an alliance with France.

On 28 January 1919, after his electoral defeat, Max Weber delivered a lecture titled "Politics as a Vocation", which commented on the subject of politics.

Shortly before he left to join the delegation in Versailles on 13 May 1919, Max Weber used his connections with the German National People's Party's deputies to meet with Erich Ludendorff.

Max Weber spent several hours unsuccessfully trying to convince Ludendorff to surrender himself to the Allies.

Max Weber thought that the German high command had failed, while Ludendorff regarded Max Weber as a democrat who was partially responsible for the revolution.

Max Weber tried to disabuse him of that notion by expressing support for a democratic system with a strong executive.

Since he held Ludendorff responsible for Germany's defeat in the war and having sent many young Germans to die on the battlefield, Max Weber thought that he should surrender himself and become a political martyr.

Frustrated with politics, Weber resumed teaching, first at the University of Vienna in 1918, then at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in 1919.

In Vienna, Max Weber filled a previously vacant chair in political economy that he had been in consideration for since October 1917.

Max Weber accepted the appointment in order to be closer to his mistress, Else von Richthofen.

In early 1920, Max Weber gave a seminar that contained a discussion of Oswald Spengler's The Decline of the West.

Max Weber respected him and privately described him as having been "a very brilliant and scholarly dilettante".

Lili Schafer, one of Max Weber's sisters, committed suicide on 7 April 1920 after the pedagogue Paul Geheeb ended his affair with her.

Max Weber thought positively of it, as he thought that her suicide was justified and that suicide in general could be an honourable act.

Max Weber was uncomfortable with his newfound role as a father figure, but he thought that Marianne was fulfilled as a woman by this event.

Max Weber wished for her to stay with the children in Heidelberg or move closer to Geheeb's so that he could be alone in Munich with his mistress, Else von Richthofen.

Max Weber left the decision to Marianne, but she said that only he could make the decision to leave for himself.

On 4 June 1920, Max Weber's students were informed that he had a cold and needed to cancel classes.

Max Weber had likely contracted the Spanish flu during the post-war pandemic and been subjected to insufficient medical care.

At the time of his death, Max Weber had not finished writing Economy and Society, his on sociological theory.

Max Weber later published a biography of her late husband in 1926 which became one of the central historical accounts of his life.

Max Weber interpreted it as having been an important part of the field's scientific nature.

Max Weber divided social action into the four categories of affectional, traditional, instrumental, and value-rational action.

Whereas Durkheim focused on society, Max Weber concentrated on the individual and their actions.

Meanwhile, compared to Marx's support for the primacy of the material world over the world of ideas, Max Weber valued ideas as motivating individuals' actions.

Max Weber had a different perspective from the two of them regarding structure and action and macrostructure in that he was open to the idea that social phenomena could have several different causes and placed importance on social actors' interpretations of their actions.

In terms of methodology, Max Weber was primarily concerned with the question of objectivity and subjectivity, distinguishing social action from social behavior and noting that social action must be understood through the subjective relationships between individuals.

Max Weber noted that the importance of subjectivity in the social sciences made the creation of fool-proof, universal laws much more difficult than in the natural sciences and that the amount of objective knowledge that social sciences were able to create was limited.

Max Weber's methodology was developed in the context of wider debates about social scientific methodology.

Max Weber's position was that the social sciences should strive to be value-free.

Max Weber interpreted methodological individualism as having had close proximity to sociology, as actions could be interpreted subjectively.

Max Weber interpreted them as having been indispensable for it.

Max Weber outlined it in "The 'Objectivity' of Knowledge in Social Science and Social Policy" and the first chapter of Economy and Society.

However, ideal types are not direct representations of reality and Max Weber warned against interpreting them as such.

Max Weber placed no limits on what could be analysed through the use of ideal types.

Max Weber believed that social scientists needed to avoid making value-judgements.

Max Weber first articulated it in his writings on scientific philosophy, including "The 'Objectivity' of Knowledge in Social Science and Social Policy" and "Science as a Vocation".

However, Max Weber disagreed with the idea that a scholar could maintain objectivity while ascribing to a hierarchy of values in the way that Rickert did, however.

Max Weber's argument regarding value-freedom was connected to his involvement in the.

Max Weber understood rationalisation as having resulted in increasing knowledge, growing impersonality, and the enhanced control of social and material life.

Max Weber admitted that it was responsible for many advances, particularly freeing humans from traditional, restrictive, and illogical social guidelines.

Max Weber understood this process as the institutionalisation of purposive-rational economic and administrative action.

Max Weber saw rationalisation as one of the main factors that set the West apart from the rest of the world.

Max Weber was looking for elective affinities between the Protestant work ethic and capitalism.

Max Weber argued that the Puritans' religious calling to work caused them to systematically obtain wealth.

Max Weber used Benjamin Franklin's personal ethic, as described in his "Advice to a Young Tradesman", as an example of the Protestant sects' economic ethic.

Max Weber argued that the origin of modern capitalism was in the religious ideas of the Reformation.

Max Weber thought that self-restraint, hard work, and a belief that wealth could be a sign of salvation were representative of ascetic Protestantism.

Max Weber's goal was to find reasons for the different developmental paths of the cultures of the Western world and the Eastern world, without making value-judgements, unlike the contemporaneous social Darwinists.

Max Weber simply wanted to explain the distinctive elements of Western civilisation.

Max Weber proposed a socio-evolutionary model of religious change where societies moved from magic to ethical monotheism, with the intermediatory steps of polytheism, pantheism, and monotheism.

In Max Weber's view, Hinduism in India, like Confucianism in China, was a barrier for capitalism.

Max Weber ended his research of society and religion in India by bringing in insights from his previous work on China to discuss the similarities of the Asian belief systems.

Max Weber noted that these religions' believers used otherworldly mystical experiences to interpret the meaning of life.

Max Weber juxtaposed such Messianic prophecies, notably from the Near East, with the exemplary prophecies found in mainland Asia that focused more on reaching to the educated elites and enlightening them on the proper ways to live one's life, usually with little emphasis on hard work and the material world.

Max Weber's next work, Ancient Judaism, was an attempt to prove this theory.

Max Weber contrasted the innerworldly asceticism developed by Western Christianity with the mystical contemplation that developed in India.

Max Weber noted that some aspects of Christianity sought to conquer and change the world, rather than withdraw from its imperfections.

Max Weber classified the Jewish people as having been a pariah people, which meant that they were separated from the society that contained them.

Max Weber examined the ancient Jewish people's origins and social structures.

Max Weber thought that Elijah was the first prophet to have risen from the shepherds.

Max Weber used the concept of theodicy in his interpretation of theology and religion throughout his corpus.

However, Max Weber disagreed with Nietzsche's emotional discussion of the topic and his interpretation of it as having been a Jewish-derived expression of slave morality.

Max Weber defined the importance of societal class within religion by examining the difference between the theodicies of fortune and misfortune and to what class structures they apply.

Accordingly, Max Weber proposed that politics is the sharing of state power between various groups, whereas political leaders were those who wielded this power.

Max Weber divided action into the oppositional and verantwortungsethik.

Max Weber listed six characteristics of an ideal type of bureaucracy:.

Max Weber thought that a hypothetical victory of socialism over capitalism would have not been able to prevent that.

Max Weber formulated a three-component theory of stratification that contained the conceptually distinct elements of social class, social status, and political party.

Max Weber maintained a sharp distinction between the terms "status" and "class", although non-scholars tend to use them interchangeably in casual use.

Max Weber interpreted life chances, the opportunities to improve one's life, as having been a definitional aspect of class.

Towards the end of his life, Weber gave two lectures, "Science as a Vocation" and "Politics as a Vocation", at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich that were on the subject of the scientific and political vocations.

Max Weber thought that only a particular type of person was able to have an academic career.

Max Weber used his own career as an example of that.

Max Weber argued that scholarship could provide certainty through its starting presumptions, despite its inability to give absolute answers.

Max Weber defined politics as having been divided into three aspects: passion, judgement, and responsibility.

Max Weber divided legitimate authority into the three categories of traditional, charismatic, and rational-legal authority.

Ultimately, Max Weber thought that the political issues of his day required consistent effort to resolve, rather than the quick solutions that the students preferred.

Max Weber primarily regarded himself as an economist, and all of his professorial appointments were in economics, but his contributions to that field were largely overshadowed by his role as a founder of modern sociology.

Max Weber's Economy and Society is an essay collection that he was working on at the time of his death in 1920.

The resulting volume included a wide range of essays dealing with Max Weber's views regarding sociology, social philosophy, politics, social stratification, world religion, diplomacy, and other subjects.

Unlike other historicists, Max Weber accepted marginal utility and taught it to his students.

In 1908, Max Weber published an article, "Marginal Utility Theory and 'The Fundamental Law of Psychophysics'", in which he argued that marginal utility and economics were not based on psychology.

Max Weber rejected the idea that marginal utility and economics were dependent on psychophysics.

In general, Max Weber disagreed with the idea that economics relied on another field.

Max Weber included a similar discussion of marginal utility in the second chapter of Economy and Society.

Max Weber wrote that the value of goods had to be determined in a socialist economy.

Max Weber himself had a significant influence on Mises, whom he had befriended when they were both at the University of Vienna in the spring of 1918.

Max Weber was strongly influenced by German idealism, particularly by neo-Kantianism.

Max Weber was exposed to it by Heinrich Rickert, who was his professorial colleague at the University of Freiburg.

Max Weber's opinions regarding social scientific methodology showed parallels with the work of contemporary neo-Kantian philosopher and sociologist Georg Simmel.

Max Weber was influenced by Kantian ethics more generally, but he came to think of it as being obsolete in a modern age that lacked religious certainties.

Max Weber was responding to Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophy's effect on modern thought.

Max Weber disliked Nietzsche's emotional approach to the subject and did not interpret it as having been a type of slave morality that was derived from Judaism.

Max Weber thought that Goethe, his Faust, and Nietzsche's Zarathustra were figures that represented the and expressed the quality of human action by ceaselessly striving for knowledge.

Marx viewed capitalism through the lens of alienation, while Max Weber used the concept of rationalisation to interpret it.

Max Weber expanded Marx's interpretation of alienation from the specific idea of the worker who was alienated from his work to similar situations that involved intellectuals and bureaucrats.

Scholars during the Cold War frequently interpreted Max Weber as having been "a bourgeois answer to Marx", but he was instead responding to the issues that were relevant to the bourgeoisie in Wilhelmine Germany.

Max Weber was instrumental in developing an antipositivist, hermeneutic, tradition in the social sciences.

Max Weber obtained permission from Marianne Weber to publish a translation of The Protestant Work Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism in his 1930 essay collection, the Collected Essays on the Sociology of Religion.

Max Weber then published a translation of Economy and Society as The Theory of Social and Economic Organization.

In 1968, a complete translation of Marianne Max Weber's prepared version of Economy and Society was published.