1.

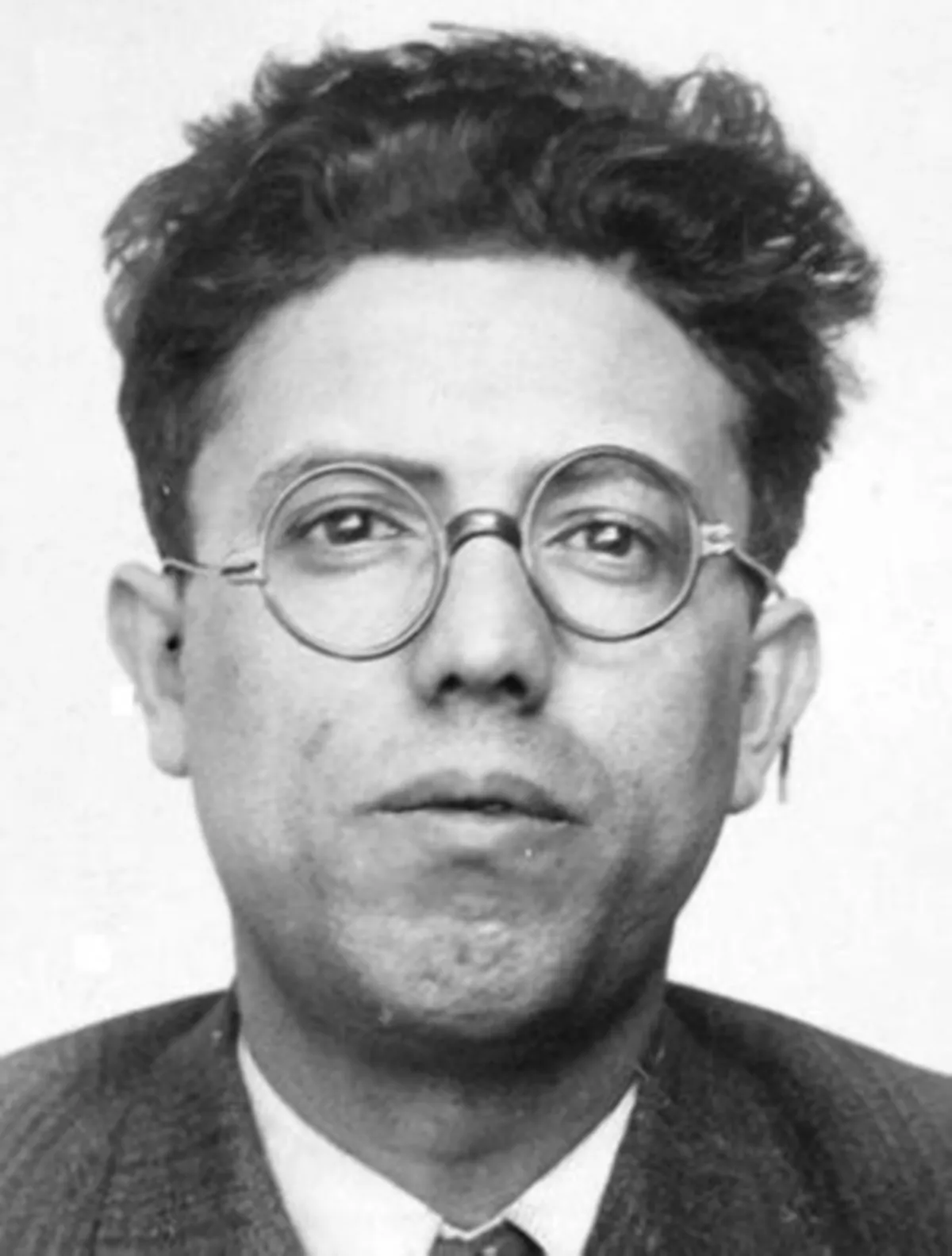

1. Mihail Roller collaborated with the Agitprop leaders Leonte Rautu and Iosif Chisinevschi, spent time in prison for his communist activity, and ultimately exiled himself to the Soviet Union, where he trained in Marxist historiography.

1.

1. Mihail Roller collaborated with the Agitprop leaders Leonte Rautu and Iosif Chisinevschi, spent time in prison for his communist activity, and ultimately exiled himself to the Soviet Union, where he trained in Marxist historiography.

Mihail Roller was branded a deviationist by the party leadership members, probably because he had unwittingly exposed their secondary roles in early communist history.

Mihail Roller died in mysterious circumstances, which do not exclude the possibility of suicide.

Mihail Roller was born in Buhusi, then a commune in Neamt County, to a Jewish family; as reported by Mihail Roller himself, his father was a rabbi, though some sources identify him as a functionary.

Mihail Roller joined the Communist Party of Germany in 1926 and the French Communist Party in 1928, working on their publications.

Mihail Roller described his beginnings with the party's Agitprop section as the start of his life as a "professional revolutionary".

Frunza believes that Mihail Roller was one of the young men working under senior activist Ana Pauker; the others were Rautu, Chisinevschi, Vasile Luca, Gheorghe Stoica, Sorin Toma, Gheorghe Vasilichi and Stefan Voicu.

Mihail Roller was again arrested in 1934 and 1938, although never sentenced due to lack of evidence.

Mihail Roller, who supervised the creation of workers' antifascist sections in Bucharest in September 1934, is mentioned as one of the PCdR and PSU activists who signed a formal protest against "the numerous abusive and illegal acts perpetrated by the organs of repression".

Mihail Roller was them moved to another position, serving as the party secretary for the Lower Danube committee, following which he served on the Committee of Defense for Antifascist Prisoners, part of the International Red Aid network.

Mihail Roller, suffering from a chronic disease later diagnosed as diabetes insipidus, would drain one of the buckets himself and fill the other.

Mihail Roller finally checked himself out of hospital and resumed clandestine work against his colleagues' advice.

Mihail Roller returned to campaigning among the workers of the Green Sector, and was appointed co-editor of an illegal newspaper, Viata Muncitoare.

In July 1940, Mihail Roller, having narrowly escaped re-arrest by the Romanian authorities, left for Bessarabia, which had been recently occupied by the Soviets.

Mihail Roller was for a while at Reni, in the Ukrainian SSR.

Mihail Roller subsequently moved to the Moldavian SSR, at Chisinau, where he began working for the city's Tobacco Plant.

Mihail Roller attended the History faculty of Moscow State University.

Mihail Roller signaled his return to Romanian historiography with the 1945 essay.

Also then, Frunza notes, Mihail Roller took part in the semi-compulsory Russification campaign, launching the agitprop slogan.

Reputedly, Mihail Roller is responsible for the refusal to accept a gift of Constantin Brancusi's modernist sculptures, thus depriving the Romanian state of a major art collection.

Mihail Roller made a controversial contribution to the field of communist censorship, joining up with Chisinevschi in the task of supervising Romanian cinema.

Mihail Roller was part of a wave of new academicians; as noted by various authors, most of these were of peripheral importance in their fields, but were staunch adherents of communism and ready to act as ideological enforcers.

Mihail Roller believed the academy should shift from its former position of "a feudal caste, a closed circle, isolated from the masses and the people's needs" into "a living and active factor in the development of our science and culture".

From 1948 to 1955, Mihail Roller was professor as well as chairman of the Romanian History department at the Political Military Academy.

Mihail Roller was a "historical reviewer" for a propaganda film retelling the 1848 events, with Geo Bogza as the screenwriter.

That year, Mihail Roller rose to head the Agitprop section's education committee.

Mihail Roller was himself supported by a number of young researchers whom he had promoted and sent to study in the Soviet Union.

Mihail Roller focused keenly on introducing ideology into higher education and party control over universities, and his general duties included supervision over science as a whole, not only history.

Mihail Roller's words indicated the limits within which historians could practice their craft.

The Mihail Roller directives are infamous for emphasizing the supposed grandeur of the Soviet Union under Stalin, but for praising Tsarist Russia and the Slavic peoples.

Plesa does give credit to Mihail Roller for ordering publication of documents from the country's medieval period, previously missing from print nearly in their entirety, and of an index to the Hurmuzachi collection that had become virtually unusable.

Mihail Roller helped plan the Romanian-Russian Museum in Bucharest and the Maxim Gorky Institute of Higher Education, devoted to training teachers of Russian language and literature.

Mihail Roller reiterated that pre-communist historians served the "bourgeois-landowning" regimes dominated by "foreign imperialists", who wished the Romanian people to remain ignorant of their history so they could more easily be exploited.

The rise of Mihail Roller coincided with a concerted effort by the new regime to wipe away traces of previous writers, so that works by historians including Giurescu, Victor Papacostea and Nicolae Benescu were eliminated from the curriculum, while some historians, such as Gheorghe Bratianu and Ion Nistor died in prison, their works hidden from public view.

Mihail Roller saw enemies among the ranks of older teachers he believed blocked the "cultural revolution", and promoted "re-education of the teaching staff".

Mihail Roller sought to imbue the educational system with a class character and make it serve the interests of workers, peasants and "progressive intellectuals", including those who had rushed to the new regime's side.

In one instance, Mihail Roller explained that, as long as the old teaching staff could include a "war criminal" such as Ion Petrovici, his own colleagues, Rautu and Chisinevschi, were fit to lecture in Marxism-Leninism at the University of Bucharest.

Mihail Roller continued to have a plenary take on education, and insisted that music should form part of schooling.

One particular area into which Mihail Roller injected communist ideology was Romanian archaeology.

Mihail Roller shifted the emphasis from Roman Dacia to pre- and post-Roman periods, reflecting Marx' and Engels' view of the Roman Empire as supremely exploitative.

Mihail Roller adapted Stalin's remarks on the "unscientific position of old bourgeois historians" whose study of Russia reportedly began with Kievan Rus' and ignored what came before.

Mihail Roller emphasized Gheorghiu-Dej's position that Romanian territory had for over a millennium been robbed by Romans and barbarians, just as it had been by French, British or German imperialists.

Mihail Roller instructed that "we must mercilessly unmask the enemies of science and the lackeys of the former bourgeois-landowning regime".

Tugui, by explaining Mihail Roller's errors, managed to attract Gheorghe Apostol and Nicolae Ceausescu as supporters.

Mihail Roller drew to his side the Romanian Academy members Constantin Daicoviciu, David Prodan and Andrei Otetea, as well as education minister Ilie Murgulescu, and later some of Roller's former collaborators, including Vasile Maciu, Victor Cherestesiu and Barbu Campina.

One effect of the moves against Mihail Roller was the 1955 firing of Aurel Roman as editor of Studii and his replacement with Otetea, so that articles started to appear without Mihail Roller's approval.

Mihail Roller died on 21 June 1958, and Plesa believes he most likely committed suicide.

Mihail Roller had married Sara Zighelboim, whose brothers Avram and Strul were communist activists during the 1930s.

Mihail Roller was originally from Bessarabia, and had returned there in 1940, shortly before Roller himself.

An urn containing Mihail Roller's ashes is housed at the Cenusa Crematorium in Bucharest.

Tismaneanu and historian Cristian Vasile note that Mihail Roller's downfall was a sacrificial offering by Leonte Rautu, who survived the "unmasking" period and was still a culture boss under the national communism of the 1960s.

Mihail Roller's contribution was reevaluated again after the Romanian Revolution of 1989 toppled communism.