1.

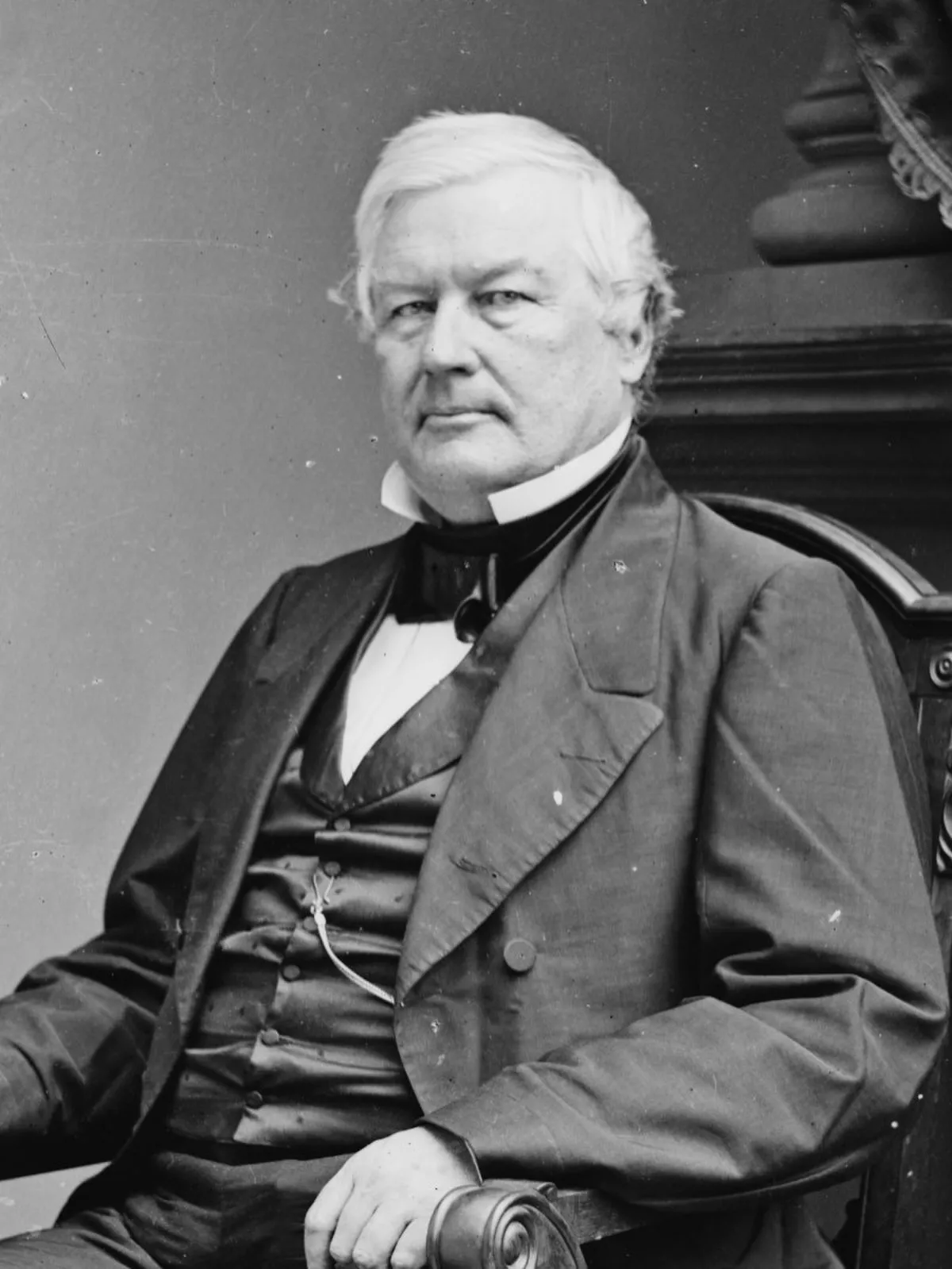

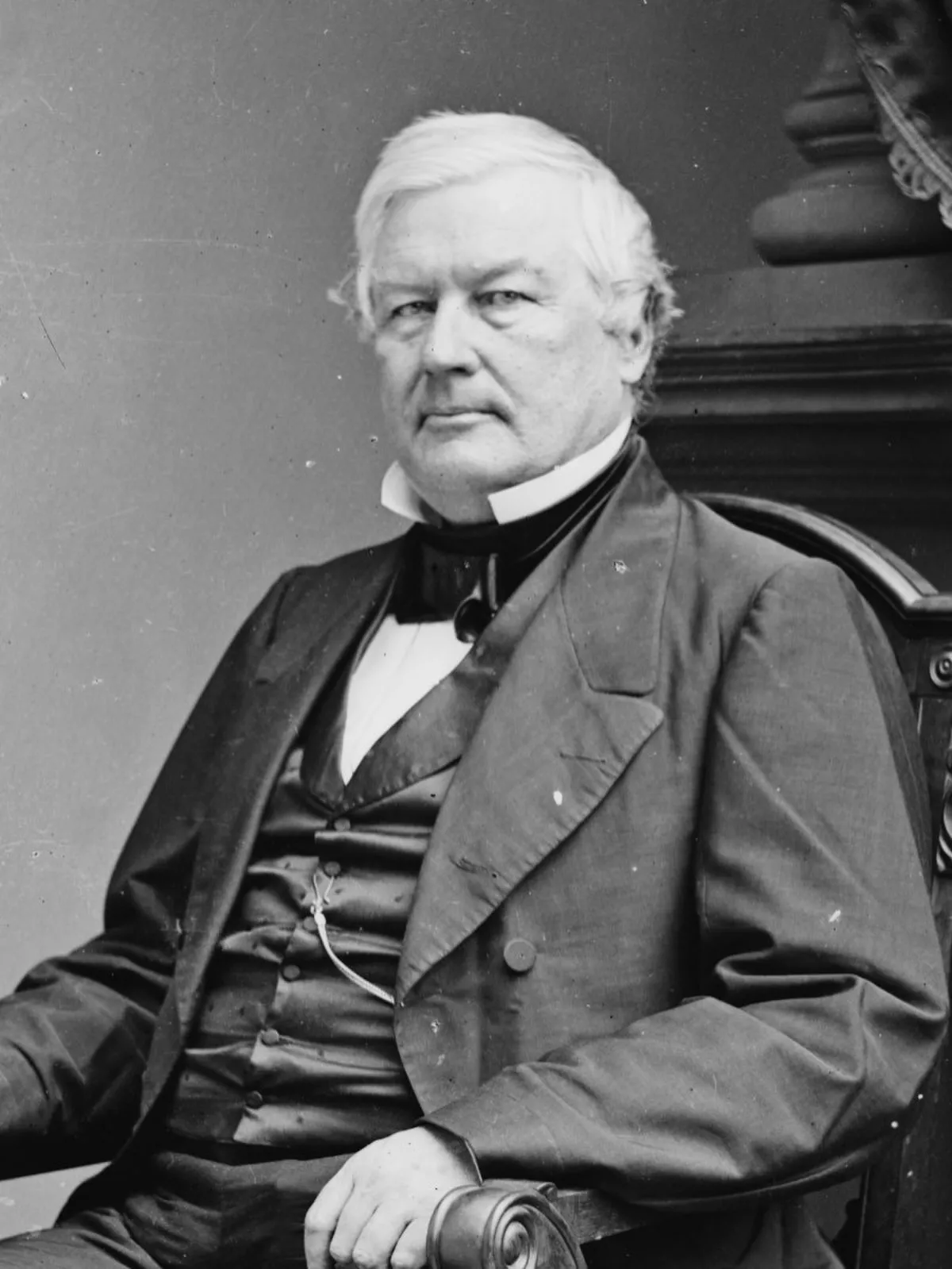

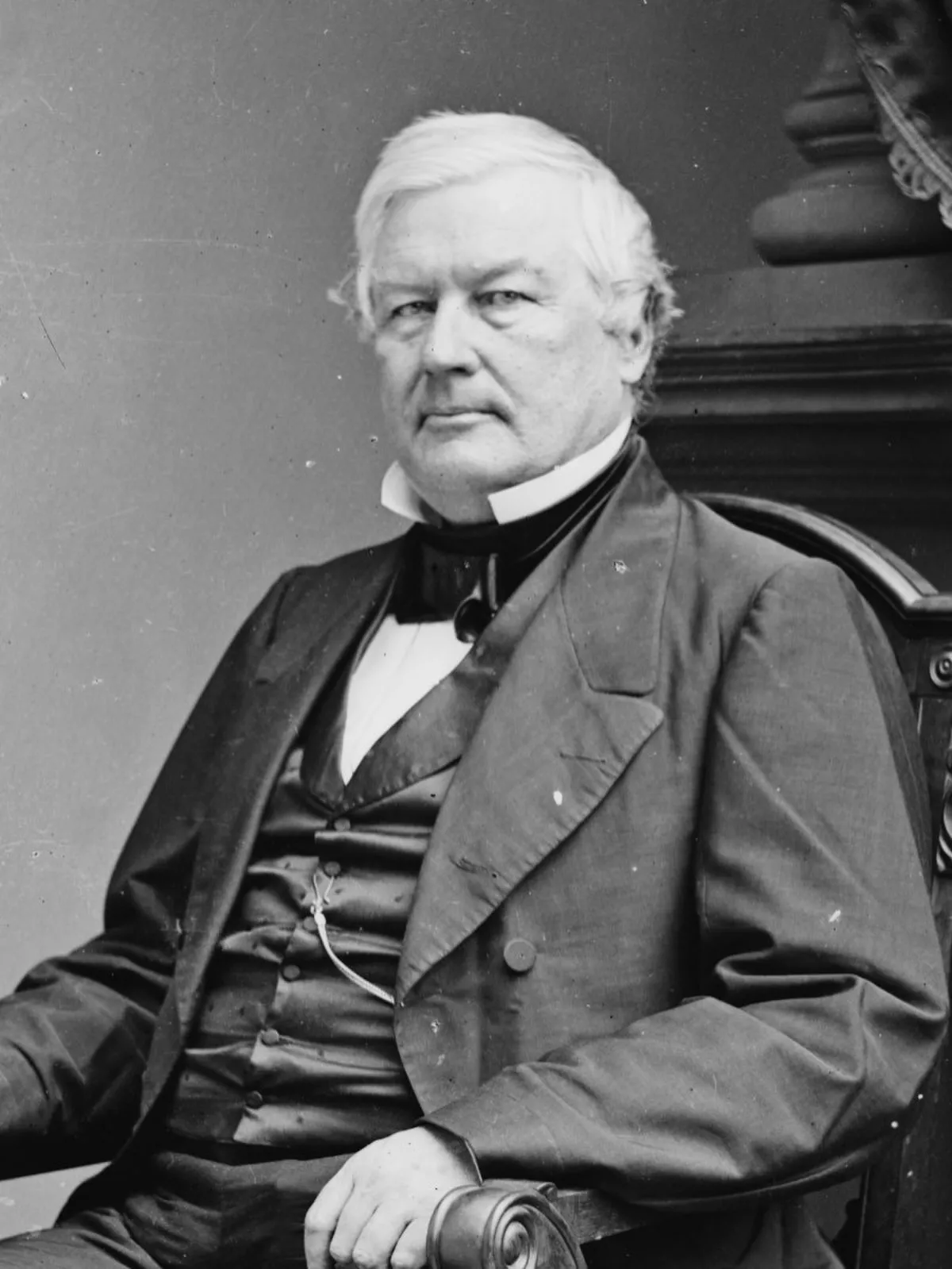

1. Millard Fillmore was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853.

1.

1. Millard Fillmore was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853.

Millard Fillmore was the last president to be a member of the Whig Party, and the last to be neither a Democrat nor a Republican.

Millard Fillmore was instrumental in passing the Compromise of 1850, which led to a brief truce in the battle over the expansion of slavery.

Millard Fillmore was born into poverty in the Finger Lakes area of upstate New York.

Millard Fillmore became prominent in the Buffalo area as an attorney and politician, and was elected to the New York Assembly in 1828 and the House of Representatives in 1832.

Millard Fillmore initially belonged to the Anti-Masonic Party, but became a member of the Whig Party as it formed in the mid-1830s.

Millard Fillmore was a rival for the state party leadership with Thurlow Weed and his protege William H Seward.

Millard Fillmore was an unsuccessful candidate for Speaker of the US House of Representatives when the Whigs took control of the chamber in 1841, but was made chairman of the Ways and Means Committee.

Unlike Taylor, Millard Fillmore supported Henry Clay's omnibus bill, the basis of the 1850 Compromise.

Millard Fillmore felt duty-bound to enforce it, though it damaged his popularity and the Whig Party, which was torn between its Northern and Southern factions.

Millard Fillmore failed to win the Whig nomination for president in 1852.

Millard Fillmore remained involved in civic interests after his presidency, including as chancellor of the University of Buffalo, which he had helped found in 1846.

Millard Fillmore was born on January 7,1800, in a log cabin, on a farm in what is Moravia, in the Finger Lakes region of New York.

Millard Fillmore's parents were Phoebe Millard and Nathaniel Fillmore; he was the second of eight children and the oldest son.

Nathaniel Fillmore and Phoebe Millard moved from Vermont in 1799 and sought better opportunities than were available on Nathaniel's stony farm, but the title to their Cayuga County land proved defective, and the Fillmore family moved to nearby Sempronius, where they leased land as tenant farmers, and Nathaniel occasionally taught school.

Millard Fillmore was relegated to menial labor, and unhappy at not learning any skills, he left Hungerford's employ.

Millard Fillmore's father placed him in the same trade at a mill in New Hope.

Millard Fillmore earned money teaching school for three months and bought out his mill apprenticeship.

Millard Fillmore left Wood after eighteen months; the judge had paid him almost nothing, and both quarreled after Fillmore had, unaided, earned a small sum by advising a farmer in a minor lawsuit.

Nathaniel again moved the family, and Millard Fillmore accompanied it west to East Aurora, near Buffalo, where Nathaniel purchased a farm that became prosperous.

Millard Fillmore taught school in East Aurora and accepted a few cases in justice of the peace courts, which did not require the practitioner to be a licensed attorney.

Millard Fillmore moved to Buffalo the following year and continued his study of law, first while he taught school and then in the law office of Asa Rice and Joseph Clary.

Later in life, Millard Fillmore said he initially lacked the self-confidence to practice in the larger city of Buffalo.

Millard Fillmore became interested in politics, and the rise of the Anti-Masonic Party in the late 1820s provided his entry.

Millard Fillmore was a delegate to the New York convention that endorsed President John Quincy Adams for reelection and served at two Anti-Masonic conventions in the summer of 1828.

At the conventions, Millard Fillmore first met political boss and future rival Thurlow Weed, then a newspaper editor, where they reportedly impressed one another.

Millard Fillmore was the leading citizen in East Aurora, having successfully sought election to the New York State Assembly, and served in Albany for three one-year terms.

Millard Fillmore proved effective anyway by promoting legislation to provide court witnesses the option of taking a non-religious oath, and in 1830, abolishing imprisonment for debt.

Millard Fillmore took his lifelong friend Nathan K Hall as a law clerk in East Aurora.

Buffalo was legally a village when Millard Fillmore arrived; although the bill to incorporate it as a city passed the legislature after he had left the Assembly, Millard Fillmore helped draft the city charter.

Millard Fillmore helped found the Buffalo High School Association, joined the lyceum, attended the local Unitarian church, and became a leading citizen of Buffalo.

Millard Fillmore was active in the New York Militia and attained the rank of major as inspector of the 47th Brigade.

In 1832 Millard Fillmore ran successfully for the US House of Representatives.

Millard Fillmore, Weed, and others realized that opposition to Masonry was too narrow a foundation to build a national party.

Weed's anti-slavery views were stronger than those of Millard Fillmore, who disliked slavery but considered the federal government powerless over it.

In Washington Millard Fillmore urged the expansion of Buffalo harbor, a decision under federal jurisdiction, and he privately lobbied Albany for the expansion of the state-owned Erie Canal.

Millard Fillmore came to the notice of the influential Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster, who took the new representative under his wing.

Millard Fillmore became a firm supporter, and they continued their close relationship until Webster's death late in Millard Fillmore's presidency.

Millard Fillmore supported building infrastructure by voting in favor of navigation improvements on the Hudson River and constructing a bridge across the Potomac River.

Millard Fillmore spent his time out of office building his law practice and boosting the Whig Party, which gradually absorbed most of the Anti-Masons.

Millard Fillmore supported the leading Whig vice-presidential candidate from 1836, Francis Granger, but Weed preferred Seward.

Millard Fillmore was embittered when Weed got the nomination for Seward but campaigned loyally, Seward was elected, and Millard Fillmore won another term in the House.

Millard Fillmore was active in the discussions of presidential candidates which preceded the Whig National Convention for the 1840 race.

Millard Fillmore initially supported General Winfield Scott but really wanted to defeat Kentucky Senator Henry Clay, a slaveholder who he felt could not carry New York State.

Millard Fillmore did not attend the convention but was gratified when it nominated General William Henry Harrison for president, with former Virginia Senator John Tyler his running mate.

Millard Fillmore organized Western New York for the Harrison campaign, and the national ticket was elected, and Millard Fillmore easily gained a fourth term in the House.

Millard Fillmore was made chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee.

Millard Fillmore remained on the fringes of that conflict by generally supporting the congressional Whig position, but his chief achievement as Ways and Means chairman was the Tariff of 1842.

Millard Fillmore prepared a bill raising tariff rates that was popular in the country, but the continuation of distribution assured Tyler's veto and much political advantage for the Whigs.

Millard Fillmore received praise for the tariff, but in July 1842, aged 42, he announced he would not seek reelection.

Tired of Washington life and the conflict that had revolved around Tyler, Millard Fillmore sought to return to his life and law practice in Buffalo.

Millard Fillmore continued to be active in the lame duck session of Congress that followed the 1842 elections and returned to Buffalo in April 1843, at age 43.

Out of office, Millard Fillmore continued his law practice and made long-neglected repairs to his Buffalo home.

Millard Fillmore remained a major political figure and led the committee that welcomed John Quincy Adams to Buffalo.

Some urged Millard Fillmore to run for vice president with Clay, the consensus Whig choice for president in 1844.

Millard Fillmore hoped to gain the endorsement of the New York delegation to the national convention, but Weed wanted the vice presidency for Seward, with Millard Fillmore as governor.

Millard Fillmore had stated that a convention had the right to draft anyone for political service, and Weed got the convention to choose Millard Fillmore, who had broad support, despite his reluctance.

Millard Fillmore was not friendly to immigrants and blamed his defeat on "foreign Catholics".

In 1846 Millard Fillmore was involved in the founding of the University of Buffalo, became its first chancellor, and served until his death in 1874.

Millard Fillmore actually came within one vote of it while he maneuvered to get the nomination for his supporter, John Young, who was elected.

The comptroller regulated the banks, and Millard Fillmore stabilized the currency by requiring that state-chartered banks keep New York and federal bonds to the value of the banknotes they issued.

Millard Fillmore persuaded Fillmore to support an uncommitted ticket but did not reveal his hopes for Seward.

Millard Fillmore eloquently described the grief of the Clay supporters, frustrated again in their battle to make Clay president.

Millard Fillmore actually agreed with many of Clay's positions but did not back him for president and was not in Philadelphia.

Under the political customs of the time, if Taylor and Millard Fillmore were elected, no one else from New York could be named to the Cabinet, meaning Weed's ambitions for Seward were frustrated, at least temporarily.

Millard Fillmore was accused of complicity in Collier's actions, but that was never substantiated.

Nevertheless, there were sound reasons for Millard Fillmore's selection, as he was a proven vote-getter from electorally crucial New York, and his track record in Congress and as a candidate showed his devotion to Whig doctrine, allaying fears he might be another Tyler were something to happen to Taylor.

Millard Fillmore thus remained at the comptroller's office in Albany and made no speeches.

Millard Fillmore interceded with Weed and assured him that Taylor was loyal to the party.

Northerners assumed that Millard Fillmore, hailing from a free state, opposed the spread of slavery.

Millard Fillmore responded to one Alabamian in a widely published letter that slavery was an evil, but the federal government had no authority over it.

Millard Fillmore assured his running mate that the electoral prospects for the ticket looked good, especially in the Northeast.

Millard Fillmore was sworn in as vice president on March 5,1849, in the Senate Chamber.

Millard Fillmore had spent the four months between the election and the swearing-in being feted by the New York Whigs and winding up affairs in the comptroller's office.

In exchange for support, Seward and Weed were allowed to designate who was to fill federal jobs in New York, and Millard Fillmore was given far less influence than had been agreed.

When Millard Fillmore discovered that after the election, he went to Taylor, which only made the warfare against Millard Fillmore's influence more open.

Millard Fillmore enjoyed one aspect of his office because of his lifelong love of learning: he became deeply involved in the administration of the Smithsonian Institution as a member ex officio of its Board of Regents.

Millard Fillmore countered the Weed machine by building a network of like-minded Whigs in New York State.

All pretense at friendship between Millard Fillmore and Weed vanished in November 1849 when they happened to meet in New York City and exchanged accusations.

Millard Fillmore presided over some of the most momentous and passionate debates in American history as the Senate debated whether to allow slavery in the territories.

The cabinet officers, as was customary when a new president took over, submitted their resignations but expected Millard Fillmore to refuse and allow them to continue in office.

Millard Fillmore had been marginalized by the cabinet members, and he accepted the resignations though he asked them to stay on for a month, which most refused to do.

Millard Fillmore is the only president who succeeded by death or resignation not to retain, at least initially, his predecessor's cabinet.

Millard Fillmore appointed his old law partner, Nathan Hall, as Postmaster General, a cabinet position that controlled many patronage appointments.

Millard Fillmore reinforced federal troops in the area and warned Bell to keep the peace.

Millard Fillmore endorsed that strategy, which eventually divided the compromise into five bills.

Millard Fillmore sent a special message to Congress on August 6,1850; disclosed the letter from Governor Bell and his reply; warned that armed Texans would be viewed as intruders; and urged Congress to defuse sectional tensions by passing the Compromise.

Millard Fillmore applied pressure to get Northern Whigs, including New Yorkers, to abstain, rather than to oppose the bill.

Nevertheless, Millard Fillmore believed himself bound by his oath as president and by the bargain that had been made in the Compromise to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act.

Millard Fillmore did so even though some prosecutions or attempts to return slaves ended badly for the government; there were acquittals, and in one incident a slave was taken from federal custody and freed by a Boston mob.

In September 1850 Millard Fillmore appointed the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints leader Brigham Young as the first governor of Utah Territory.

Millard Fillmore made many speeches along the way from the train's rear platform, urged acceptance of the Compromise, and later went on a tour of New England with his Southern cabinet members.

Millard Fillmore appointed one justice to the Supreme Court of the United States and four to United States district courts, including his law partner and cabinet officer, Nathan Hall, to the federal district court in Buffalo.

When Supreme Court Justice Levi Woodbury died in September 1851 with the Senate not in session, Millard Fillmore made a recess appointment of Benjamin Robbins Curtis to the Court.

Millard Fillmore oversaw two highly competent Secretaries of State: Daniel Webster, and after Webster's 1852 death, Edward Everett.

Millard Fillmore was particularly active in Asia and the Pacific, especially with regard to Japan, which then still prohibited nearly all foreign contact.

Millard Fillmore was a staunch opponent of European influence in Hawaii.

Taylor had pressed Portugal for payment of American claims dating as far back as the War of 1812 and had refused offers of arbitration, but Millard Fillmore gained a favorable settlement.

Millard Fillmore had difficulties regarding the Spanish colony of Cuba since many Southerners hoped to see the island as an American slave territory.

The historian Elbert B Smith, who wrote of the Taylor and the Fillmore presidencies, suggested that Fillmore could have had war against Spain had he wanted.

Many Southerners, including Whigs, supported the filibusters, and Millard Fillmore's response helped to divide his party as the 1852 election approached.

Kossuth was feted by Congress, and Millard Fillmore allowed a White House meeting after he had received word that Kossuth would not try to politicize it.

Millard Fillmore refused to change the American policy of remaining neutral.

Millard Fillmore had become unpopular with northern Whigs for signing and enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act but still had considerable support from the South, where he was seen as the only candidate capable of uniting the party.

Once the convention passed a party platform endorsing the Compromise as a final settlement of the slavery question, Millard Fillmore was willing to withdraw.

Millard Fillmore found that many of his supporters could not accept Webster and that his action would nominate Scott.

Webster was far more unhappy at the outcome than was Millard Fillmore, who refused the secretary's resignation.

Webster died in October 1852, but during his final illness, Millard Fillmore effectively acted as his own Secretary of State without incident, and Everett stepped competently into Webster's shoes.

Millard Fillmore contented himself with pointing out the prosperity of the nation and expressing gratitude for the opportunity to serve.

Millard Fillmore left office on March 4,1853, succeeded by Pierce.

Millard Fillmore was the first president to return to private life without independent wealth or possession of a landed estate.

Millard Fillmore was bereaved again on July 26,1854, when his only daughter, Mary, died of cholera.

Millard Fillmore retained many supporters, planned an ostensibly nonpolitical national tour, and privately rallied disaffected Whig politicians to preserve the Union and to back him in a run for president.

Millard Fillmore made public appearances opening railroads and visiting the grave of Senator Clay but met with politicians outside the public eye during the late winter and spring of 1854.

Many northern foes of slavery, such as Seward, gravitated toward the new Republican Party, but Millard Fillmore saw no home for himself there.

Millard Fillmore was encouraged by the success of the Know Nothings in the 1854 midterm elections in which they won in several states of the Northeast and showed strength in the South.

Later that year Millard Fillmore went abroad, and stated publicly that as he lacked office he might as well travel.

Millard Fillmore spent March 1855 to June 1856 in Europe and the Middle East.

Millard Fillmore carefully weighed the political pros and cons of meeting with Pius.

Millard Fillmore nearly withdrew from the meeting when he was told that he would have to kneel and kiss the Pope's hand.

Millard Fillmore's allies were in full control of the American Party and arranged for him to get its presidential nomination while he was in Europe.

The Know Nothing convention chose Millard Fillmore's running mate: Andrew Donelson of Kentucky, the nephew by marriage and once-ward of President Jackson.

Millard Fillmore made a celebrated return in June 1856 by speaking at a series of welcomes, beginning with his arrival at a huge reception in New York City and continuing across the state to Buffalo.

Millard Fillmore rarely spoke about the immigration question, focused on the sectional divide, and urged the preservation of the Union.

Once Millard Fillmore was back home in Buffalo, he had no excuse to make speeches, and his campaign stagnated through the summer and fall of 1856.

The historian Allan Nevins wrote that Millard Fillmore was not a Know Nothing or a nativist, offering as support that Millard Fillmore was out of the country when the nomination came and had not been consulted about running.

Millard Fillmore considered his political career to have ended with his defeat in 1856.

Millard Fillmore again felt inhibited from returning to the practice of law.

Millard Fillmore decried Buchanan's inaction as states left the Union and wrote that although the federal government could not coerce a state, those advocating secession should be regarded as traitors.

When Lincoln came to Buffalo en route to his inauguration, Millard Fillmore led the committee selected to receive him, hosted him at his mansion, and took him to church.

Once the Civil War began, Millard Fillmore supported Lincoln's efforts to preserve the Union.

Millard Fillmore commanded the Union Continentals, a corps of home guards of men over 45 from upstate New York.

Millard Fillmore was criticized in many newspapers and called a Copperhead and even a traitor.

Millard Fillmore retained his position as Buffalo's leading citizen and was among those selected to escort the body when Lincoln's funeral train passed through Buffalo, but many remained angry at him for his wartime positions.

Millard Fillmore supported President Andrew Johnson's Reconstruction policies since he felt that the nation needed to be reconciled as quickly as possible.

Millard Fillmore devoted most of his time to civic activities.

Millard Fillmore aided Buffalo in becoming the third American city to have a permanent art gallery, the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy.

Millard Fillmore stayed in good health almost to the end of his life.

Millard Fillmore had a stroke in February 1874, and died on March 8, at age 74, after a second stroke.

The US Senate sent three of its members to honor Millard Fillmore, including former vice president Hannibal Hamlin.

Millard Fillmore is ranked by historians and political scientists as one of the worst US presidents.

Millard Fillmore's handling of major political issues, such as slavery, has led many historians to describe him as weak and inept.

Millard Fillmore's name has become a byword in popular culture for easily forgotten and inconsequential presidents.

The Millard Fillmore administration resolved a controversy with Portugal left over from the Taylor administration, smoothed over a disagreement with Peru over guano islands, and peacefully resolved disputes with Britain, France, and Spain over Cuba, all without the US going to war or losing face.

Grayson applauds Millard Fillmore's firm stand against Texas's ambitions in New Mexico during the 1850 crisis.

When, as President, Millard Fillmore sided with proslavery elements in ordering enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, he all but guaranteed that he would be the last Whig President.