1.

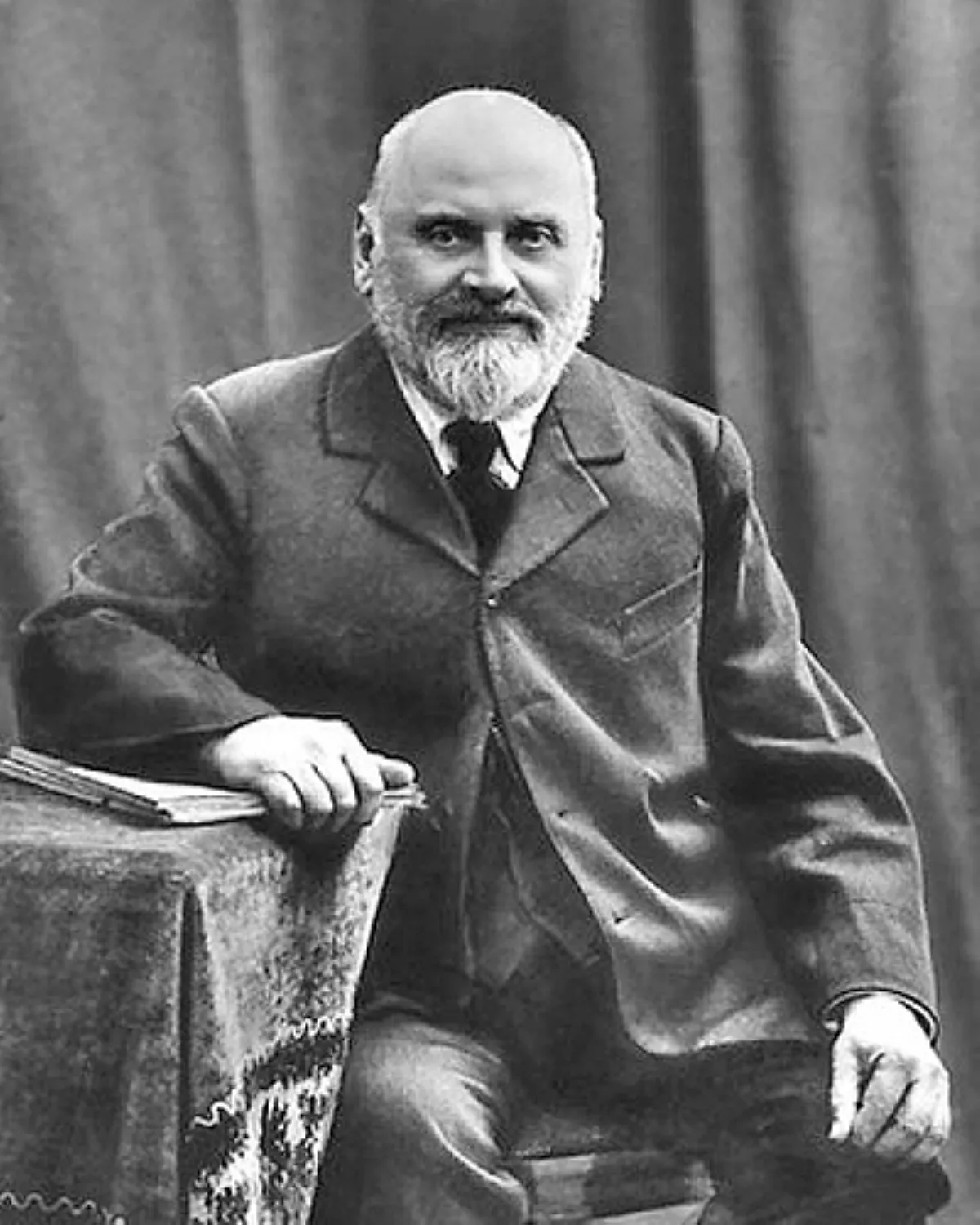

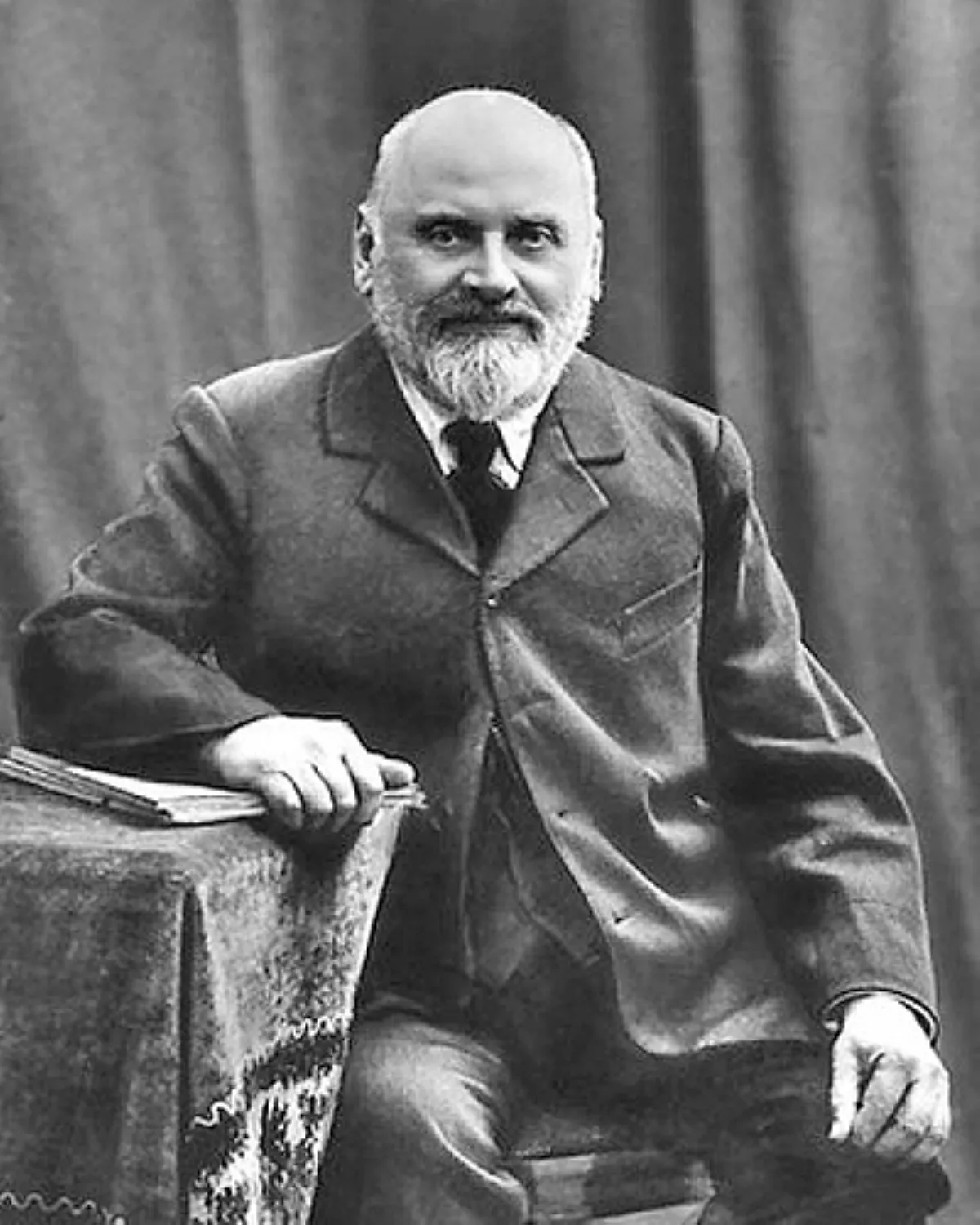

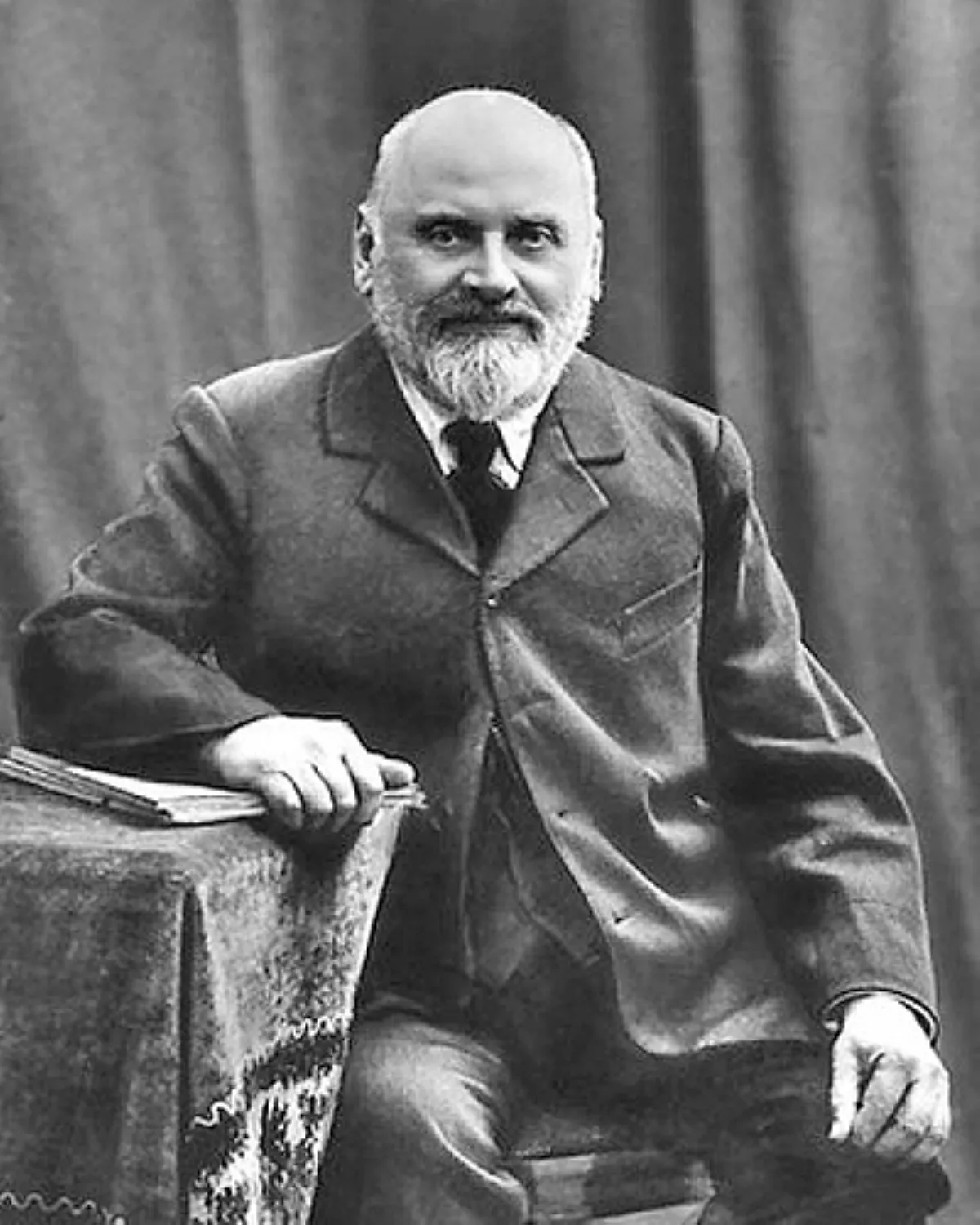

1. Mily Balakirev began his career as a pivotal figure, extending the fusion of traditional folk music and experimental classical music practices begun by composer Mikhail Glinka.

1.

1. Mily Balakirev began his career as a pivotal figure, extending the fusion of traditional folk music and experimental classical music practices begun by composer Mikhail Glinka.

For several years, Mily Balakirev was the only professional musician of the group; the others were amateurs limited in musical education.

Mily Balakirev imparted to them his musical beliefs, which continued to underlie their thinking long after he left the group in 1871, and encouraged their compositional efforts.

Mily Balakirev began work on a second symphony, Symphony No 2 in D minor in 1900, but did not complete the work until 1908.

Mily Balakirev's father, Alexey Konstantinovich Balakirev, was a titular councillor who belonged to the ancient dynasty founded by Ivan Vasilievich Balakirev, a Moscow boyar and voivode who led the Russian army against the Khanate of Kazan during the 1544 expedition.

The name Mily Balakirev was a traditional male name in her family.

Mily Balakirev gave piano lessons to her son since the age of four, and when he turned ten she took him to Moscow during the summer holidays for a course of ten piano lessons with Alexander Dubuque.

Eisrach and Ulybyshev allowed Mily Balakirev to rehearse the count's private orchestra in rehearsals of orchestral and choral works.

Mily Balakirev left the Alexandrovsky Institute in 1853 and entered the University of Kazan as a mathematics student, along with his friend Pyotr Boborykin, who later became a novelist.

Mily Balakirev was noted in local society as a pianist and was able to supplement his limited finances by taking pupils.

Mily Balakirev's holidays were spent either at Nizhny Novgorod or on the Ulybyshev country estate at Lukino, where he played numerous Beethoven sonatas to help his patron with his book on the composer.

Mily Balakirev made his debut in a university concert in February 1856, playing the completed movement from his First Piano Concerto.

Nevertheless, his time with Glinka had sparked a passion for Russian nationalism within Mily Balakirev, leading him to adopt the stance that Russia should have its own distinct school of music, free from Southern and Western European influences.

Mily Balakirev had started meeting other important figures who would abet him in this goal in 1856, including Cesar Cui, Alexander Serov, the Stasov brothers and Alexander Dargomyzhsky.

Mily Balakirev now gathered around him composers with similar ideals, whom he promised to train according to his own principles.

Mily Balakirev had been trained as a pianist and had to discover his own way to becoming a composer.

Mily Balakirev, who had never had any systematic course in harmony and counterpoint and had not even superficially applied himself to them, evidently thought such studies quite unnecessary.

Mily Balakirev instantly felt every technical imperfection or error, he grasped a defect in form at once.

Mily Balakirev's eventual undoing was his demand that his students' musical tastes coincide exactly with his own, with the slightest deviation prohibited.

The other members of The Five became interested in writing opera, a genre Mily Balakirev did not consider highly, after the success of Alexander Serov's opera Judith in 1863, and gravitated toward Alexander Dargomyzhsky as a mentor in this field.

Mily Balakirev was outspoken in his opposition to Anton Rubinstein's efforts.

Anton Rubinstein was at that time the only Russian able to live on his art, while Mily Balakirev had to live on income from piano lessons and recitals played in the salons of the aristocracy.

Mily Balakirev attacked Rubinstein for his conservative musical tastes, especially for his leaning on German masters such as Mendelssohn and Beethoven, and for his insistence on professional musical training.

Glinka had taken the article badly, and Mily Balakirev likewise took Rubinstein's criticism personally.

Lomakin was appointed director, with Mily Balakirev serving as his assistant.

Mily Balakirev spent the summer of 1862 in the Caucasus, mainly in Essentuki, and was impressed enough by the region to return there the following year and in 1868.

Mily Balakirev noted down folk tunes from that region and from Georgia and Iran; these tunes would play an important part in his musical development.

In 1864, Mily Balakirev considered writing an opera based on the folk legend of the Firebird, but abandoned the project due to the lack of a suitable libretto.

Mily Balakirev completed his Second Overture on Russian Themes that same year, which was performed that April at a Free School concert and published in 1869 as a "musical picture" with the title 1000 Years.

Mily Balakirev started a Symphony in C major, of which he completed much of the first movement, scherzo and finale by 1866.

Mily Balakirev began a second piano concerto in the summer of 1861, with a slow movement thematically connected with a requiem that occupied him at the same time.

Mily Balakirev did not finish the opening movement until the following year, then set aside the work for 50 years.

Mily Balakirev suffered from periods of acute depression, longed for death and thought about destroying all his manuscripts.

Mily Balakirev was still able to complete some works quickly.

Mily Balakirev began the original version of Islamey in August 1869, finishing it a month later.

Mily Balakirev intermittently spent time editing Glinka's works for publication, on behalf of the composer's sister, Lyudmilla Shestakova.

Mily Balakirev suspected Smetana and others were influenced by pro-Polish elements of the Czech press, which labeled the production a "Tsarist intrigue" paid for by the Russian government.

Mily Balakirev had difficulties with the production of Ruslan and Lyudmila under his direction, with the Czechs initially refusing to pay for the cost of copying the orchestral parts, and the piano reduction of the score, from which Balakirev was conducting rehearsals, mysteriously disappearing.

Mily Balakirev encouraged Rimsky-Korsakov and Borodin to complete their first symphonies, whose premieres he conducted in December 1865 and January 1869 respectively.

Mily Balakirev conducted the first performance of Mussorgsky's The Destruction of Sennacherib in March 1867 and the Polonaise from Boris Godunov in April 1872.

The choice of Berlioz as foreign conductor was widely lauded, but Mily Balakirev's appointment was seen less enthusiastically.

Mily Balakirev had conducted Tchaikovsky's symphonic poem Fatum and the "Characteristic Dances" from his opera The Voyevoda at the RMS, and Fatum had been dedicated to Mily Balakirev.

Mily Balakirev sent two notes to Balakirev; the first alerted him to Elena Pavlovna's planned presence in Moscow, and the second thanked Balakirev for criticisms he had made about Fatum just after conducting it.

In 1880, Mily Balakirev received a copy of the final version of the score of Romeo from Tchaikovsky, care of the music publisher Besel.

Tchaikovsky initially refused, but two years later changed his mind, partly due to Mily Balakirev's continued prodding over the project.

When Lomakin resigned as director of the Free Music School in February 1868, Mily Balakirev took his place there.

Mily Balakirev decided to recruit popular soloists and found Nikolai Rubinstein ready to help.

Mily Balakirev decided to raise the social level of the RMS concerts by attending them personally with her court.

Mily Balakirev then hoped that a solo recital in his hometown of Nizhny Novgorod in September 1870 would restore his reputation and prove profitable.

Borodin wrote to Rimsky-Korsakov that he wondered whether Mily Balakirev's condition was little better than insanity.

Mily Balakirev was especially concerned about Balakirev's coolness toward musical matters, and hoped he would not follow the example of author Nikolai Gogol and destroy his manuscripts.

Mily Balakirev took a five-year break from music, and withdrew from his musical friends, but did not destroy his manuscripts; instead he stacked them neatly in one corner of his house.

Mily Balakirev finally resigned in 1874 and was replaced by Rimsky-Korsakov.

Financial distress forced Mily Balakirev to become a railway clerk on the Warsaw railroad line in July 1872.

In 1876, Mily Balakirev slowly began reemerging into the music world, but without the intensity of his former years.

In 1881, Mily Balakirev was offered the directorship of the Moscow Conservatory, along with the conductorship of the Moscow branch of the Russian Musical Society.

Mily Balakirev held this post until 1895, when he took his final retirement and composed in earnest.

Mily Balakirev did not take advantage of Belyayev's services in these areas, as he felt that they promoted inferior music, and lowered the quality of Russian music.

Musicologist Richard Taruskin asserted that another reason Mily Balakirev did not participate with the Belyayev circle was that he was not comfortable participating in a group at which he was not at its center.

Unlike his earlier days, when he played works in progress at gatherings of The Five, Mily Balakirev composed in isolation.

Mily Balakirev was aware that younger composers now considered his compositional style old-fashioned.

Except initially for Glazunov, whom he brought to Rimsky-Korsakov as a prodigy, and his later acolyte Sergei Lyapunov, Mily Balakirev was ignored by the younger generation of Russian composers.

Mily Balakirev died on 29 May 1910 and was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in Saint Petersburg.

Mily Balakirev became belligerent in his religious conversations with friends, insistent that they cross themselves and attend church with him.

Mily Balakirev became important in the history of Russian music through both his works and his leadership.

Mily Balakirev wrote in all the genres cultivated by Frederic Chopin except the Ballade, cultivating a comparable charm.

The other keyboard composer who influenced Mily Balakirev was Franz Liszt, apparent in Islamey as well as in his transcriptions of works by other composers and the symphonic poem Tamara.

Between his two Overtures on Russian Themes, Mily Balakirev became involved with folk song collecting and arranging.

Mily Balakirev chose his themes from folk song collections available at the time he composed the piece, taking Glinka's Kamarinskaya as a model in taking a slow song for the introduction, then for the fast section choosing two songs compatible in structure with the ostinato pattern of the Kamarinskaya dance song.

Mily Balakirev's use of two songs in this section was an important departure from the model, as it allowed him to link the symphonic process of symphonic form with Glinka's variations on an ostinato pattern, and in contrasting them treat the songs symphonically instead of merely decoratively.

The Second Overture on Russian Themes shows an increased sophistication as Mily Balakirev utilizes Beethoven's technique of deriving short motifs from longer themes so that those motifs can be combined into a convincing contrapuntal fabric.

Mily Balakirev began his First Symphony after completing the Second Overture but cut work short to concentrate on the Overture on Czech Themes, recommencing on the symphony only 30 years later and not finishing it until 1897.

Mily Balakirev further cultivated the orientalism of Glinka's opera Ruslan and Lyudmila, making it a more consistent style.

Mily Balakirev evokes both the poem's setting of the mountains and gorges of the Caucasus and the angelic and demonically seductive power of the title character.