1.

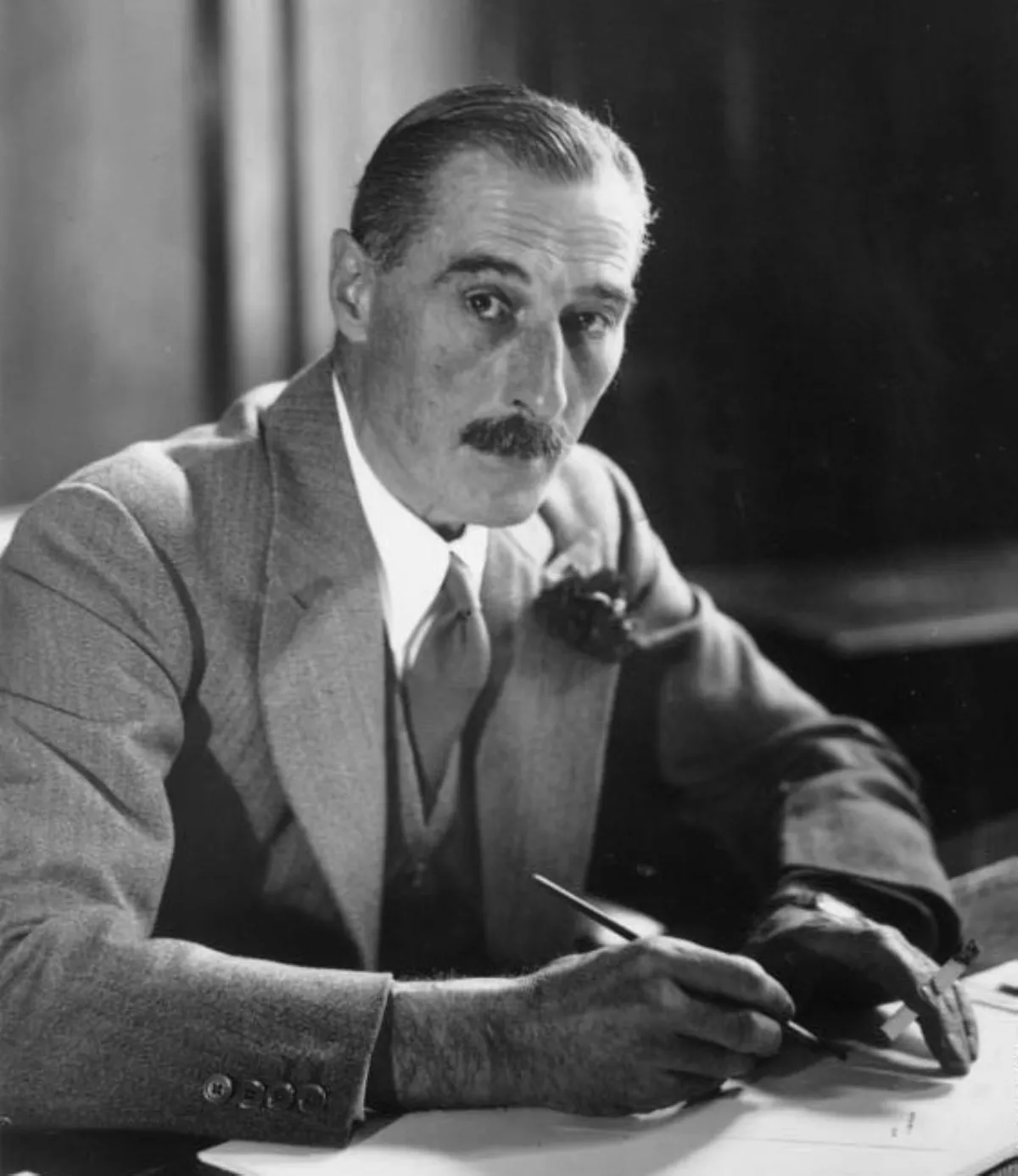

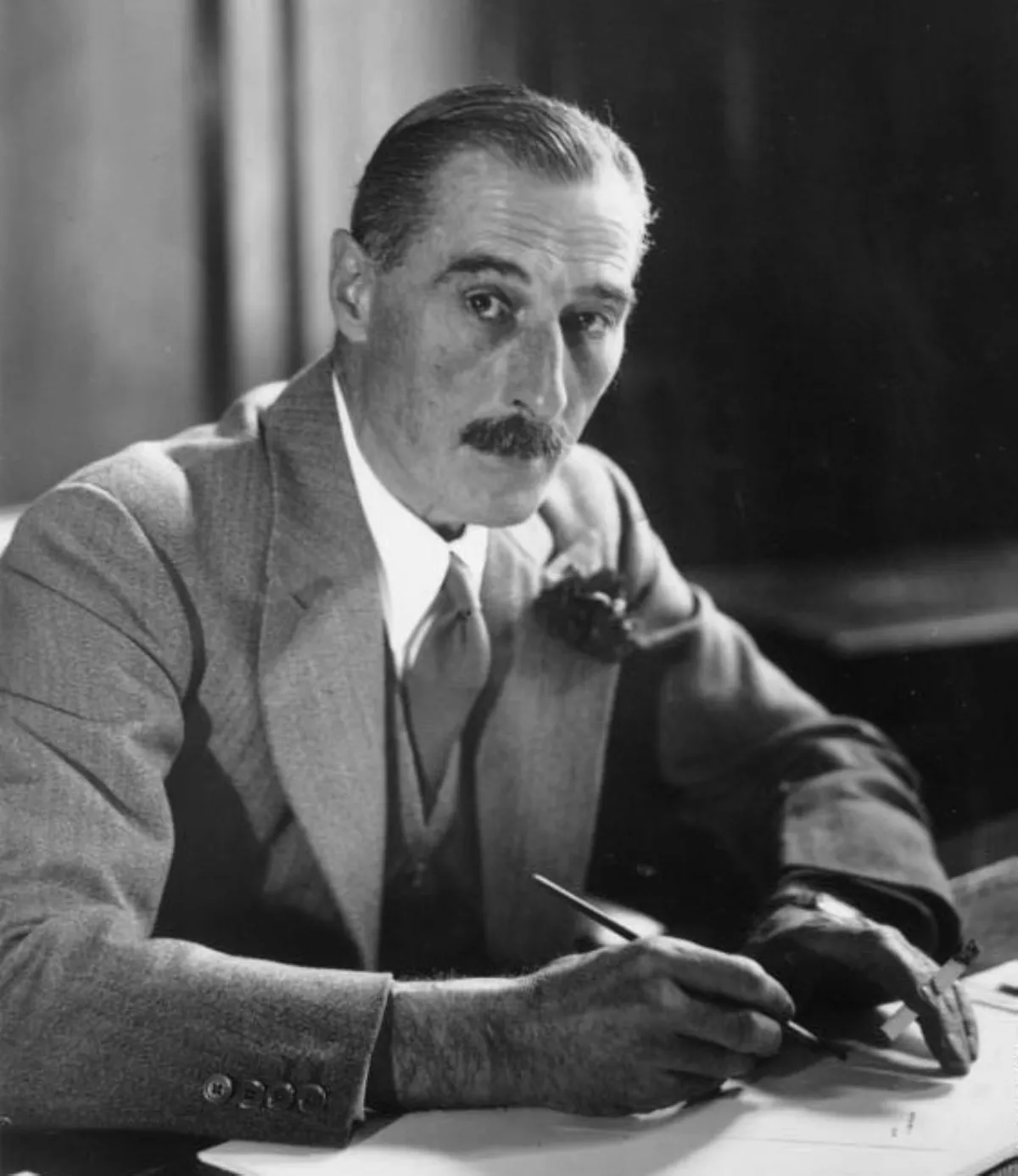

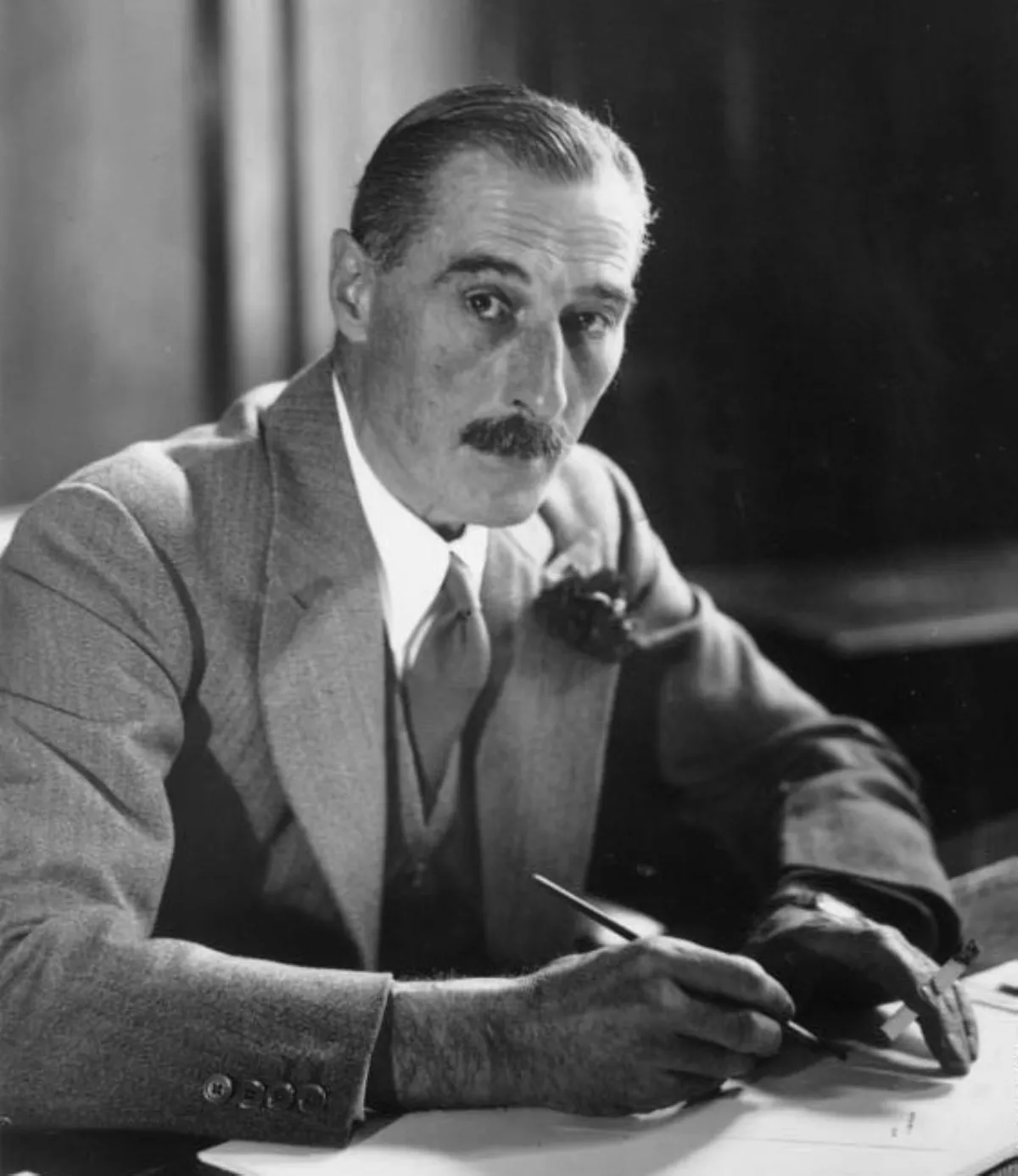

1. Sir Nevile Meyrick Henderson was a British diplomat who served as the ambassador of the United Kingdom to Germany from 1937 to 1939.

1.

1. Sir Nevile Meyrick Henderson was a British diplomat who served as the ambassador of the United Kingdom to Germany from 1937 to 1939.

Nevile Henderson's uncle was Reginald Hargreaves, who married Alice Liddell, the original of Alice in Wonderland.

Nevile Henderson was very attached to the countryside of Sussex, especially his home of Sedgwick, and wrote in 1940: "Each time that I returned to England the white cliffs of Dover meant Sedgwick for me, and when my mother died in 1931 and my home was sold by my elder brother's wife, something went out of my life which nothing can replace".

Nevile Henderson was extremely close to his mother, Emma, a strong-willed woman who had successfully managed the estate at Sedgwick after her husband's death in 1895 and developed the gardens of Sedgwick so well that they were photographed by Country Life magazine in 1901.

Nevile Henderson called his mother "the presiding genius of Sedgwick" who was a "wonderful and masterful woman if ever there was one".

Nevile Henderson was educated at Eton and joined the Diplomatic Service in 1905.

Nevile Henderson was, as one historian notes, "something of a snob", although another historian states that his snobbishness mostly derived from the death of his mother.

Nevile Henderson had a great love of sports, guns and hunting, and those who knew him noted he was always most happy when he was out on the hunt.

Nevile Henderson was known for his love of clothing and always wore the most expensive Savile Row suits and a red carnation.

Nevile Henderson was considered to be one of the best-dressed men in the Foreign Office, being obsessed with the proper fashion even during long-distance rail voyages.

Nevile Henderson never married, but his biographer, Peter Neville, wrote that "women played an important role in his life".

Nevile Henderson had wanted a posting in France, rather than Turkey, where he constantly complained to his superiors about being sent.

Nevile Henderson was forceful in upholding the British claim to the region, but was prepared to yield to Turkish demands for Constantinople.

Nevile Henderson argued that Britain had been shown to have a very weak hand by the Chanak Crisis in 1922, which revealed that public opinion in Britain and its dominions was unwilling go to war over the issue.

Nevile Henderson served as an envoy to France in 1928 to 1929 and as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia between 1929 and 1935.

Nevile Henderson did not want the latter post, whose British legation was considered to be an unglamorous post, compared to the "grand embassies" in Paris, Berlin, Rome, Moscow, Vienna, Madrid and Washington.

Nevile Henderson had been lobbying for a major post in the Paris embassy and, expecting to move back to Paris soon, continued to pay the rent for his apartment there for some time after moving to Belgrade.

Nevile Henderson was in close confidence with Prince Paul, the regent of Yugoslavia on behalf of Alexander's son, Peter II, who was only a boy.

In January 1935, the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, Sir Robert "Van" Vansittart sharply rebuked him for a letter he had written to Paul in which Nevile Henderson strongly supported Yugoslavia's complaints against Italy.

On 28 May 1937, Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden appointed Nevile Henderson to be ambassador in Berlin.

Nevile Henderson's promotion from being the ambassador in Buenos Aires to being the ambassador in Berlin, which was regarded as one of the "grand embassies" in the Foreign Office, was a major boost to his ego.

Nevile Henderson wrote at the time that he believed he had been "specially selected by Providence for the definite mission of, I trusted, helping to preserve the peace of the world".

Nevile Henderson wrote in his 1940 The Failure of a Mission that he was determined "to see the good side of the Nazi regime as well as the bad, and to explain as objectively as I could its aspirations and viewpoint to His Majesty's Government".

Nevile Henderson was to say that Chamberlain had authorised him to commit "calculated indiscretions" in the pursuit of peace, but the German-born American historian Abraham Ascher wrote that no evidence has emerged to support that claim.

Neville wrote that the charge that Nevile Henderson was pro-Nazi was incorrect since Nevile Henderson had advocated the revision of Versailles in Germany's favour long before Hitler had come to power.

Nevile Henderson first met Goring on 24 May 1937 and admitted to having a "real personal liking" for him.

In one of his "calculated indiscretions", Nevile Henderson broke with the unwritten rule in the Foreign Office that ambassadors should never criticise their predecessors by telling Goring that Sir Eric Phipps had been too insensitive towards German concerns.

Nevile Henderson detested Ribbentrop and wrote to King George VI that Ribbentrop was "eaten up with conceit".

Nevile Henderson argued that the Nazi regime was divided into factions, which he called the "moderates" and the "extremists".

Nevile Henderson regarded Goring as the leader of the "moderates", which included the Wehrmacht officer corps, the Reichsbank officials, the professional diplomats of the Foreign Office and the officials of the Reich Ministry of Economy, and the "extremists" were Ribbentrop, Josef Goebbels and Heinrich Himmler.

Nevile Henderson argued that Britain should work to revise the international system established by the Treaty of Versailles in favour of Germany, which would strengthen the "moderates" in Germany and weaken the "extremists", as the best way of preventing another world war.

Nevile Henderson regarded all aims of the "moderates", such as the return of the Free City of Danzig, the Polish Corridor, Upper Silesia, the lost colonies in Africa, the Anschluss with Austria and the Sudetenland joining Germany as being reasonable and just.

Nevile Henderson called the rally a most impressive event attended by some 140,000 Germans, who were full of enthusiasm for the regime.

Nevile Henderson wrote that his hosts in Nuremberg went out of their way to be friendly towards him by giving him a luxurious apartment to stay in and inviting him to sumptuous meals with the best German food and wine being served.

On 16 March 1938, Nevile Henderson wrote to the Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, to set out his view: "British interests and the standard of morality can only be combined if we insist upon the fullest possible equality for the Sudeten minority of Czechoslovakia".

Unlike Basil Newton, the British minister in Prague, Nevile Henderson initially advocated plans to turn Czechoslovakia into a federation and wrote to Halifax "how to secure, if we can, the integrity of Czechoslovakia".

At a meeting with Vojtech Mastny, the Czechoslovak minister in Berlin, on 30 March 1938, Nevile Henderson admitted that Czechoslovakia had the best record for the treatment of its minorities in Eastern Europe but criticised Czechoslovakia for being a unitary state, which he argued caused too many problems in a state made up of Czechs, Slovaks, Magyars, Germans, Poles and Ukrainians.

Weizsacker and Nevile Henderson both wanted a peaceful "chemical dissolution of Czechoslovakia", instead of the "mechanical dissolution" of war, which was favoured by Hitler and Ribbentrop.

Nevile Henderson spoke with Hitler after he gave his speech at the rally and reported that Hitler "even while addressing the Hitler Youth" was so nervous that he could not relax, which led to Nevile Henderson to conclude, "His abnormality seemed to me even greater than ever".

Nevile Henderson did not believe that Hitler wanted all of Czechoslovakia and wrote to Halifax that all that Hitler wanted was to secure "fair and honorable treatment for the Austro- and Sudeten Germans", even at the price of war, but Hitler "hates war as much as anyone".

Nevile Henderson was ambassador at the time of the 1938 Munich Agreement and counselled Chamberlain to agree to it.

Sir Oliver Harvey, Halifax's Principal Private Secretary, wrote in September 1938, "Nevile Henderson's very presence here is a danger as he infects the Cabinet with his gibber".

In October 1938, Nevile Henderson was diagnosed with cancer, which caused him to leave for London.

Unlike Nevile Henderson, who tended to gloss over the sufferings of German Jews, Ogilvie-Forbes gave far more attention to Nazi anti-Semitism.

When Nevile Henderson returned to Berlin on 13 February 1939, his first action was to call a meeting of the senior staff of the British embassy, where he castigated Ogilvie-Forbes for his negative tone in his dispatches during his absence and announced that all dispatches to London would have to conform to his views, and that any diplomat who reported otherwise would be removed from the Foreign Office.

In February 1939, Nevile Henderson cabled the Foreign Office in London:.

On 6 March 1939, Nevile Henderson sent a lengthy dispatch to Lord Halifax that attacked almost everything that Ogilvie-Forbes had written while he was in charge of the British embassy.

Besides disallowing Ogilvie-Forbes, Nevile Henderson attacked British newspapers for negative coverage of Nazi Germany, especially the Kristallnacht, and demanded that the Chamberlain government impose censorship to end all negative coverage of the Third Reich.

Nevile Henderson praised Hitler for his "sentimentality" and wrote "the humiliation of the Czechs [at the Munich conference] was a tragedy", but it was Benes's own fault for failing to give autonomy to the Sudeten Germans while he still had the chance.

Nevile Henderson handed over a protest note and was intermittently recalled to London.

The US State Department made it clear to the Foreign Office that it felt that Nevile Henderson would be an embarrassment in Washington.

When Nevile Henderson asked for leave to visit Canada in the spring of 1939, he was told that he would have to give to the Foreign Office copies of any planned lectures before he gave them since no-one in the Chamberlain government still trusted Nevile Henderson to "speak sensibly" about Germany.

Coulondre added that Nevile Henderson had told him that the German demand for the Free City of Danzig to be allowed to rejoin Germany was justified in his view and that the introduction of conscription in Britain did not mean that British policies towards Germany were changing.

However, Nevile Henderson believed that Britain needed to deter Germany from attacking Poland while Britain pressured Poland into concessions and so favoured the "peace front" with the Soviet Union, despite his distrust, as the best form of deterrence.

Nevile Henderson argued that Britain should rearm secretly, as public rearming would encourage the belief that Britain planned to go to war against Germany.

Ambassador Nevile Henderson, who had long advocated concessions to Germany, recognised that here was a deliberately conceived alibi the German government had prepared for a war it was determined to start.

Nevile Henderson had to deliver Britain's final ultimatum on the morning of 3 September 1939 to Ribbentrop that if hostilities between Germany and Poland did not cease by 11 am that day, a state of war would exist between Britain and Germany.

Nevile Henderson spoke highly of some members of the Nazi regime, including Reichsmarschall Hermann Goring but not Ribbentrop.

Nevile Henderson had been on friendly terms with members of the Astors' Cliveden set, which supported appeasement.

Nevile Henderson wrote in his memoirs how eager Prince Paul of Yugoslavia had been to illustrate his military plans to counter Mussolini's projected assault on Dalmatia when the main body of the Italian Royal Army had been sent overseas.

Nevile Henderson was then staying at the Dorchester Hotel, in London.