1.

1. Nichiren declared that the Lotus Sutra alone contains the highest truth of Buddhism and that it is the only sutra suited for the Age of Dharma Decline.

1.

1. Nichiren declared that the Lotus Sutra alone contains the highest truth of Buddhism and that it is the only sutra suited for the Age of Dharma Decline.

Nichiren insisted that the sovereign of Japan and its people should support only this form of Buddhism and eradicate all others, or they would face social collapse and environmental disasters.

Nichiren advocated the faithful recitation of the title of the Lotus Sutra, Namu Myoho-renge-kyo, as the only effective path to Buddhahood in this very life, a path which he saw as accessible to all people regardless of class, education or ability.

Nichiren held that Shakyamuni and all other Buddhist deities were manifestations of the Original Eternal Buddha of the Lotus Sutra, which he equated with the Lotus Sutra itself and its title.

Nichiren declared that believers of the Sutra must propagate it even though this would lead to many difficulties and even persecution, which Nichiren understood as a way of "reading" the Lotus Sutra with one's very body.

Nichiren believed that the spread of the Lotus Sutra teachings would lead to the creation of a pure buddhaland on earth.

Nichiren was a prolific writer and his biography, temperament, and the evolution of his beliefs has been gleaned primarily from his writings.

Nichiren claimed to be the reincarnation of bodhisattva Visistacaritra, and designated six senior disciples, which later led to much disagreement after his death.

Nichiren was exiled twice and some of his followers were imprisoned or killed.

Nichiren was posthumously bestowed the title by the Emperor Go-Kogon in 1358.

Some see Nichiren as being the Bodhisattva Visistacaritra, while other sects claim that Nichiren was actually the Primordial or "True Buddha".

The main narrative of Nichiren's life has been constructed from extant letters and treatises he wrote, counted in one collection as 523 complete writings and 248 fragments.

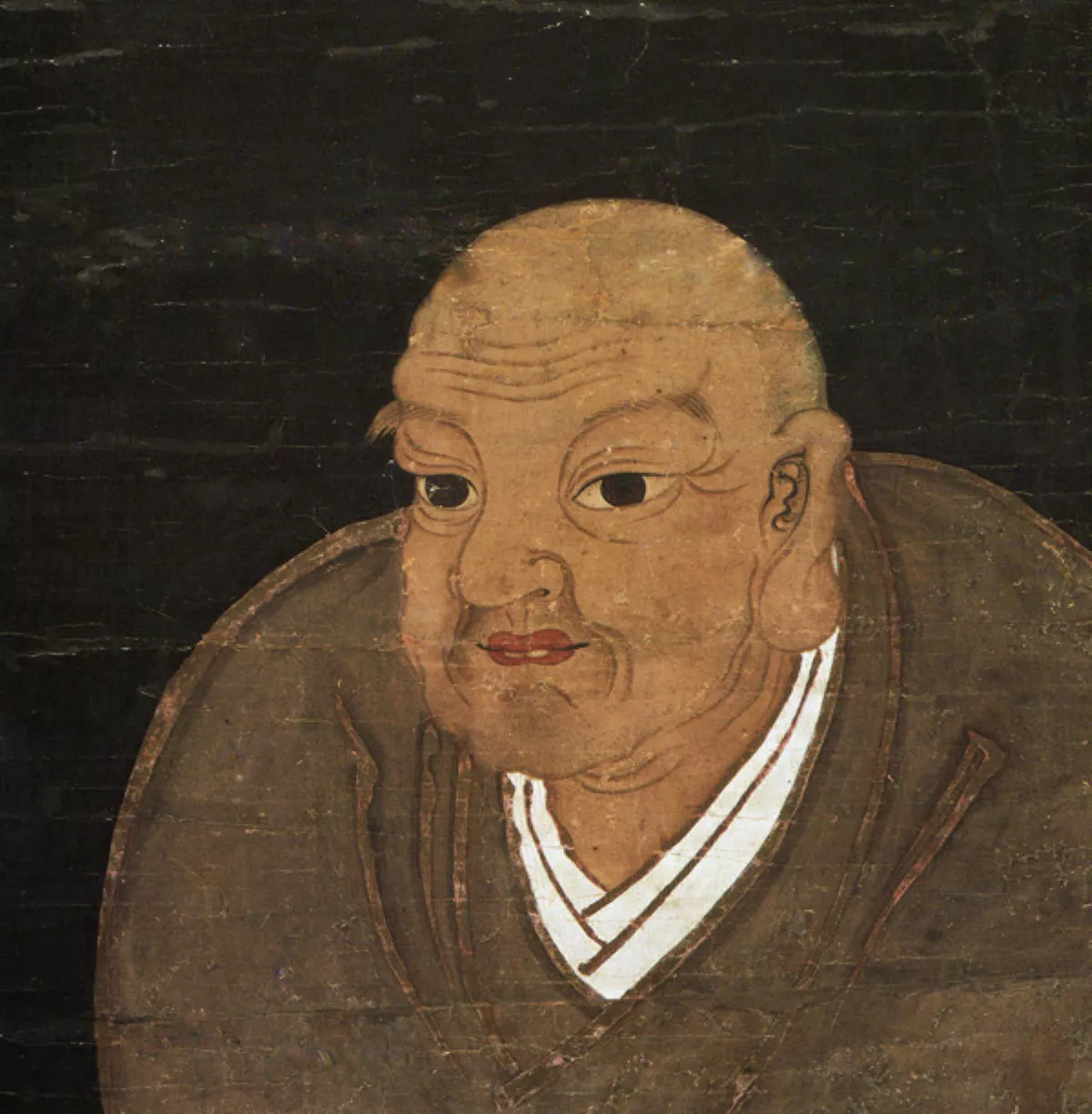

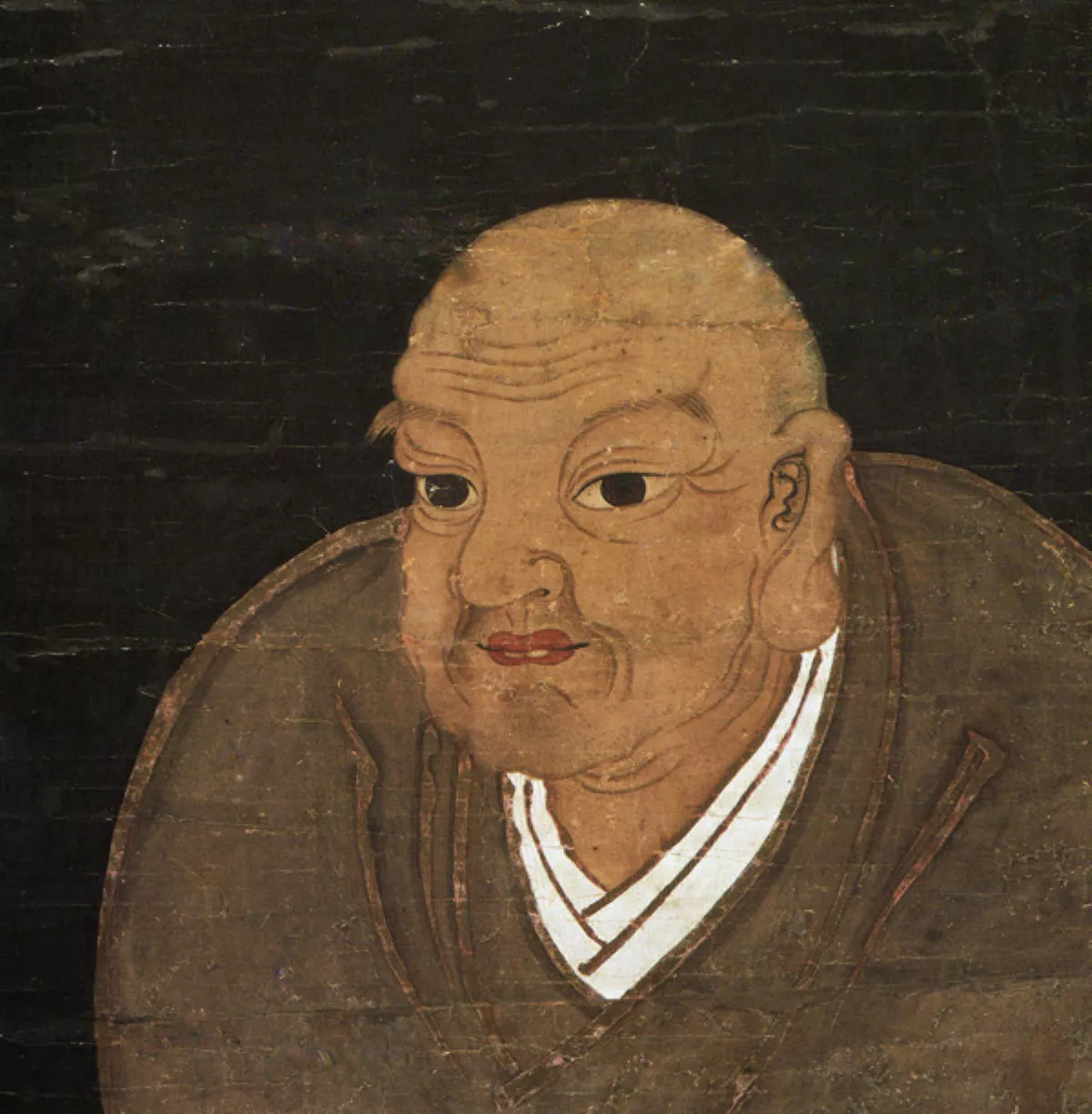

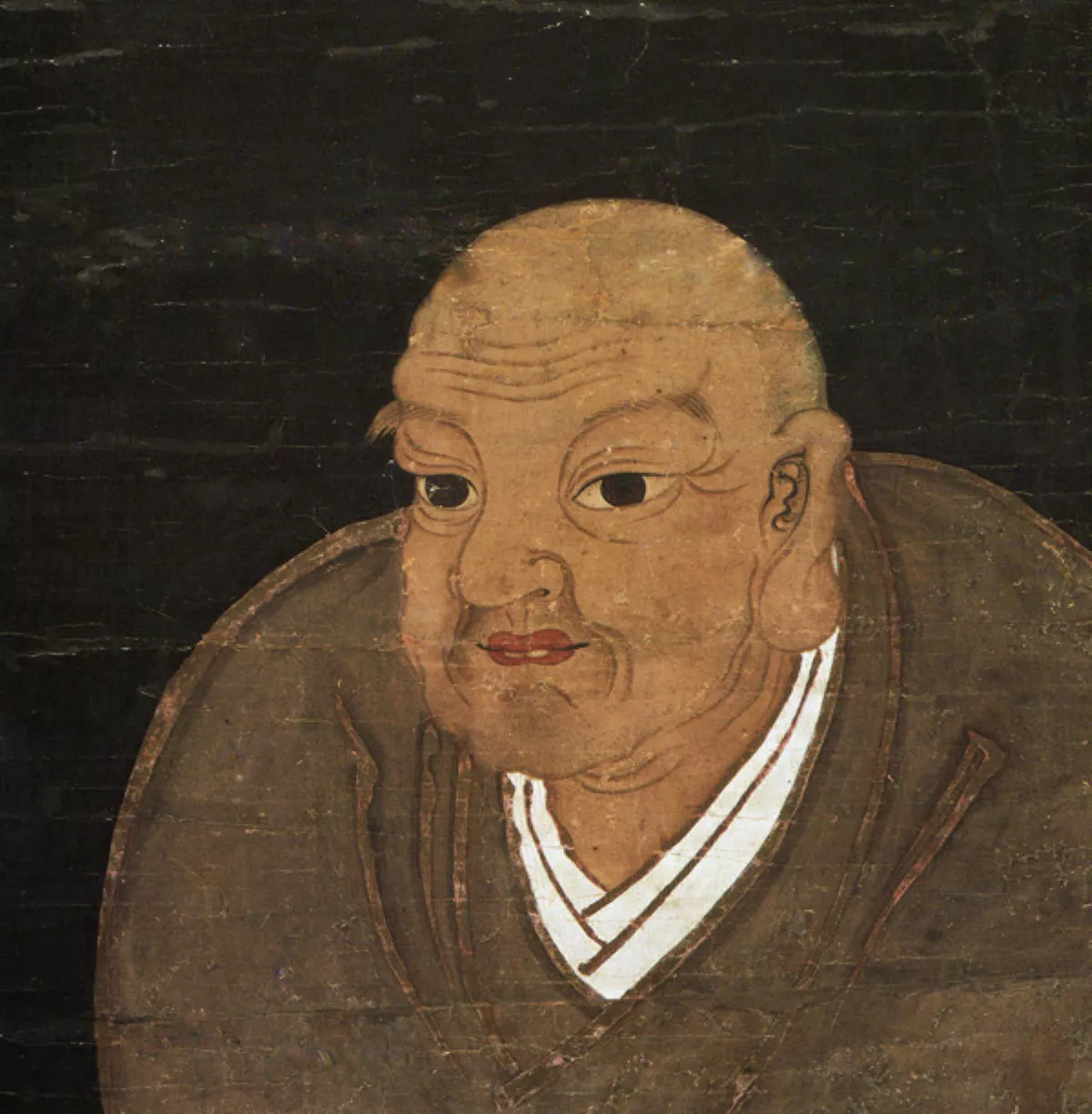

Several hagiographies about Nichiren and are reflected in various pieces of artwork about incidents in his life.

Nichiren is most well known for his promotion of Lotus Sutra devotion over and above all other Buddhist scriptures and teachings.

Nichiren held that reciting the title of the Lotus Sutra encompassed all Buddhist teachings, and thus it could lead to enlightenment in this life.

Nichiren remains a controversial figure among scholars who cast him as either a fervent nationalist or a social reformer with a transnational religious vision.

Nichiren is often compared to other religious figures who shared similar rebellious and revolutionary drives to reform degeneration in their respective societies or schools.

Nichiren was born in the village of Kominato, Nagase District, Awa Province.

Nichiren described himself as "the son of a Sendara, "a son born of the lowly people living on a rocky strand of the out-of-the-way sea," and "the son of a sea-diver.

Nichiren's father was Mikuni-no-Tayu Shigetada, known as Nukina Shigetada Jiro ; and his mother was Umegiku-nyo.

The exact site of Nichiren's birth is believed to be currently submerged off the shore from present-day Kominato-zan Tanjo-ji near a temple in Kominato that commemorates his birth.

Nichiren was formally ordained at sixteen years old and took the Buddhist name, Rencho meaning "Lotus Growth".

Between the years 1233 and 1253 Nichiren studied the major Buddhist traditions in Japan at that time, including Tendai, Pure Land Buddhism and Shingon.

Nichiren later left Seicho-ji for Kamakura where he studied Pure Land Buddhism, a school that stressed salvation through the invocation of the name Amitabha, a practiced called nembutsu.

Nichiren studied Zen which had been growing in popularity in both Kamakura and Kyoto.

Nichiren next traveled to Mount Hiei, the center of Japanese Tendai Buddhism, where he scrutinized the school's original doctrines, including Pure Land and Tendai Esoteric Buddhism.

Nichiren envisioned Japan as the country where the true teaching of Buddhism would be revived and the starting point for its worldwide spread.

At his lecture, it is construed, Nichiren vehemently attacked Honen, the founder of Pure Land Buddhism, and its practice of chanting the Nembutsu.

In so doing he earned the animosity of the local steward, Tojo Kagenobu, and eventually Nichiren was forced to leave the temple.

Nichiren then moved to a hermitage in the hills around Kamakura.

Nichiren sought scriptural references to explain the unfolding of natural disasters and then wrote a series of works which, based on the Buddhist theory of the non-duality of the human mind and the environment, attributed the sufferings to the weakened spiritual condition of people, thereby causing the Kami to abandon the nation.

Nichiren was challenged to a religious debate with leading Kamakura prelates in which, by his account, they were swiftly dispatched.

Nichiren's critics had influence with key governmental figures and spread slanderous rumors about him.

Nichiren began to emphasize the purpose of human existence as being the practice of the bodhisattva ideal in the real world which entails undertaking struggle and manifesting endurance.

Nichiren suggested that he is a model of this behavior, a "votary" of the Lotus Sutra.

Nichiren suffered a broken arm and a sword cut across his forehead, and one of his followers was killed.

Nichiren sent 11 letters to influential leaders reminding them about his predictions in the Rissho Ankoku Ron.

Nichiren redoubled his efforts and continued to give regular lectures as more people joined the movement.

Nichiren accelerated his polemics against the non-Lotus teachings the government had been patronizing at the very time it was attempting to solidify national unity and resolve.

Nichiren's claims drew the ire of the influential religious figures of the time and their followers, especially the Shingon priest Ryokan.

Nichiren considered this as his second remonstration to the government.

Whatever the case, Nichiren himself believed he had undergone a transformative experience.

Nichiren was then exiled to a second location, on Sado Island in the Sea of Japan.

Nichiren was accompanied by a few disciples and in the first winter they endured terrible cold, food deprivation, and threats from local inhabitants.

Nichiren scholars describe a clear shift in both tone and message in letters written before his Sado exile and those written during and after.

The tactics of the bakufu suppression of the Nichiren community included exile, imprisonment, land confiscation, or ousting from clan membership.

In some of his writings during a second exile, Nichiren began to identify himself with two major Lotus Sutra bodhisattvas: Sadaparibhuta and Visistacaritra.

Nichiren identified himself with the bodhisattva Visistacaritra to whom Shakyamuni entrusted the future propagation of the Lotus Sutra, seeing himself in the role of leading a vast outpouring of Bodhisattvas of the Earth who pledged to liberate the oppressed.

Nichiren had attracted a small band of followers in Sado who provided him with support and disciples from the mainland began visiting him and providing supplies.

At this point Nichiren was transferred to much better accommodations.

Nichiren found doctrinal rational for this in the 16th chapter of the Lotus Sutra.

In 1274, after his two predictions of foreign invasion and political strife were seemingly actualized by the first attempted Mongol invasion of Japan along with an unsuccessful coup within the Hojo clan, Nichiren was pardoned by the Shogunate authorities.

Nichiren wrote that his innocence and the accuracy of his predictions caused the regent Hojo Tokimune to intercede on his behalf.

Nichiren used the audience as yet another opportunity to remonstrate with the government.

Nichiren led a widespread movement of followers in Kanto and Sado mainly through his prolific letter-writing.

Nichiren showed the ability to provide a compelling narrative of events that gave his followers a broad perspective of what was unfolding.

Nichiren's followers encouraged him to travel to the hot springs in Hitachi for their medicinal benefits.

Nichiren was encouraged by his disciples to travel there for the warmer weather, and to use the land offered by Hagiri Sanenaga for recuperation.

Nichiren's teachings developed over the course of his career and their evolution can be seen through the study of his writings as well as in the annotations he made in his personal copy of the Lotus Sutra, the so-called Chu-hokekyo.

Nichiren set a precedent for Buddhist activism centuries before its emergence in other Buddhist schools.

Nichiren held adamantly that his teachings would permit a nation to right itself and ultimately lead to world peace.

Nichiren held that since Japan had entered Mappo, teachings like nembutsu, Zen and esoteric practices were no longer effective - only Lotus Sutra practices were effective.

Nichiren believed that the world had entered the final age of degeneration.

Furthermore, Nichiren held that due to their lack of virtue, Japan was being abandoned by the gods, leading to the natural disasters which were occurring and to the threat of Mongol invasion.

Nichiren argued that the various protective deities had abandoned Japan because the court and the people had turned away from the true Dharma of the Lotus Sutra to false teachings.

Nichiren asserted, in contrast to other schools, Mappo was the best possible time to be alive, since now the Bodhisattvas of the Earth would appear teach and spread the Lotus Sutra.

Nichiren taught Five Principles or five criteria for evaluating Buddhist teachings and establishing the supremacy of the Lotus Sutra as the highest and best teaching for Japan at his time.

Nichiren stressed the idea that the Buddha's pure land is immanent in this present Saha world and that all beings have the innate potential to attain Buddhahood in this very body, though this can only be achieved by relying on the Lotus Sutra.

Nichiren was influenced by earlier ideas taught by Kukai and Saicho, who had taught the possibility of becoming a Buddha in this life and the belief all beings are "originally enlightened".

Nichiren saw ichinen sanzen as pointing to the potential for Buddhahood in all beings and to the actualization of Buddhahood itself, which encompasses and illuminates all other realms.

Nichiren associated these with the "trace" teaching of the first half of the Lotus Sutra and with the "origin" teaching of the latter half of the sutra respectively.

Nichiren saw ichinen sanzen as the ultimate truth and the heart of the Lotus Sutra, writing that "only the Tiantai ichinen sanzen is the path of attaining Buddhahood".

Nichiren held that this teaching of the interfusion of all reality, the ultimate meaning of the Lotus Sutra, could now be realized solely through devotion to the sutra, especially by the practice of faithfully chanting the title of the sutra.

Nichiren thus tasked his future followers with a mandate to accomplish it.

Nichiren appropriated the structure of a universally accessible single practice but substituted the nembutsu with the recitation of the daimoku, while affirming that this practice could lead to Buddhahood in this life, instead of just leading to birth in a pure land.

Since Nichiren deemed the world to be in a degenerate age where most teachings were ineffective, he held that people required a simple and effective method to attain Buddhahood.

Nichiren held that these three Dharmas are the concrete manifestations of "the actualization of ichinen sanzen" specific to the age of Dharma Decline.

The first proof is "documentary," whether the religion's fundamental texts, here the writings of Nichiren, make a lucid case for the eminence of the religion.

Nichiren sees this as the only truly effective practice, the superior Buddhist practice for this time.

Nichiren was influenced by Zhiyi, who argued in his Profound Meaning of the Lotus Sutra that the title of the sutra contains the meaning of the entire sutra.

Nichiren held that the term Renge represents how the cause and the effect are one.

Furthermore, Nichiren saw this practice as going beyong the self-power other-power dichotomy used by Pure Land Buddhism:.

Nichiren saw the daimoku as granting worldly benefits, such as healing and protection from harm.

Nichiren created a unique honzon style in the form of a calligraphic mandala representing the entire cosmos, specifically centered around the Lotus Sutras ceremony in the air above Vulture Peak.

Nichiren inscribed many of these mandalas as personal honzon for his followers.

Nichiren drew on earlier visual representations of the Lotus Sutra and was influenced by contemporary figures like Myoe and Shinran who created calligraphic honzon for their disciples.

Nichiren's gohonzons contain the daimoku written vertically in the center.

Nichiren discusses the ordination platform or place of worship, less frequently than the other great secret Dharmas for the mappo era.

However, Nichiren held that the merit of the precepts was already contained within the daimoku, and that embracing the Lotus Sutra was the only true precept in the final Dharma age.

Nichiren left the fulfillment of the kaidan to his successors and its interpretation has been a matter of heated debate.

Nichiren urged his followers to "quickly reform the tenets you hold in your heart", and to reflect on their behavior as human beings.

Nichiren made a "great vow" that he and all his followers would create the conditions for a peaceful Dharmic nation.

Nichiren's teachings embraced a new view which held that "nation" referred to the land and the people.

Nichiren was unique among his contemporaries in charging the actual government in power, as responsible for peace and for the thriving of Dharma.

Nichiren saw his struggles to spread the Lotus as reflecting and re-enacting the efforts of the bodhisattvas which appear in the Lotus Sutra, mainly Sadaparibhuta and Visistacaritra.

Nichiren constantly enjoined his followers to continue to spread the teaching of the Lotus and to keep working to create a buddha-land in this world in the future.

Nichiren's ideas were vociferously attacked by many authors including Myoe and Jokei.

Nichiren himself saw countering slander of the Dharma as a key pillar of Buddhist practice.

At age 32, Nichiren began a career of denouncing several Mahayana schools of his time and declaring what he asserted was the correct teaching.

Nichiren remained non-violent even while experiencing persecution and living in a world in which established sects like the Tendai school wielded armies of warrior monks to attack their critics.

Nichiren held that depending on the time and place, one could use either of these.

Nichiren believed that since Japan was a Buddhist country that had entered the Final Dharma age in which people were discarding the Lotus Sutra, it was necessary to make use of confrontational shakubuku when encountering certain people.

Nichiren saw his critiques as a compassionate act, since he was convinced only the Lotus could lead to liberation in this age.

Nichiren's polemics included sharp criticisms of the Pure Land, Shingon, Zen, and Ritsu schools.

The core of Nichiren's critique was that these schools had turned people away from the Lotus Sutra, making them focus on other thing like a postmortem destination, secret and elitist master disciple transmissions and monastic rules.

Nichiren critiqued the Japanese Tendai school for its appropriation of esoteric elements.

Nichiren held that Zen was devilish in its belief that attaining enlightenment was possible through a "secret transmission outside the scriptures", and that Ritsu was thievery because it hid behind token deeds such as public works.

In spite of his critiques, Nichiren did not reject all other Buddhist traditions or practices in full.

Nichiren's combative preaching led to many attacks and persecutions against him and his followers.

Nichiren saw these attacks as signifying his role as a "votary of the Lotus Sutra", one who bears witness to the truth of the sutra through their own life and is thus assured of enlightenment.

Nichiren claimed to be "reading [the Lotus Sutra] with his body", that is directly and physically experiencing the words of the sutra instead of just reciting or thinking about it.

Nichiren saw it as his personal mission to actively face these trials, and claimed he found great meaning and joy in them.

Nichiren even expressed appreciation to his tormentors for giving him the opportunity to serve as an envoy of the Buddha.

Furthermore, for Nichiren, experiencing trials and even death in service to the Lotus Sutra was a way to attain Buddhahood.

Nichiren saw his sufferings as redemptive opportunities to quickly transform his karma and repay his debts to the triple gem, to one's parents, nation, and to all of beings.

Nichiren further held that encountering great trials for the sake of the Lotus guaranteed one's future Buddhahood, and he compared this to the radical acts of self-sacrifice found in the Mahayana sutras.

Nichiren was well aware of the struggles his followers faced in their lives.

Nichiren taught them that facing these challenges would lead to a sense of inner freedom, peace of mind, and to an understanding of the Dharma.

Nichiren accepted the classic Buddhist views on karma which taught that a person's current conditions were the cumulative effect of past thoughts, words, and actions.

Nichiren thus taught that when confronting difficult karmic situations, chanting of the daimoku would open the wisdom of the Buddha and transform one's karma, awakening a universal concern for one's society.

In some of his letters, Nichiren extended his theory of facing persecution for the Lotus Sutra to personal problems like familial discord or illness.

Nichiren encouraged his followers to take ownership of negative life events, and to view them as opportunities to repay karmic debts and to practice Dharma, which help could shorten the length of these events.

For Nichiren, finding joy in experiencing the Lotus Sutra through one's personal life experience was of paramount in importance.

Nichiren held that peace of mind in the face of life's challenges is precisely what the Lotus Sutra meant by its statement that those to uphold the sutra will have peace and security.

Nichiren defends a profound nonduality between subjective existence and the surrounding world, the non-separation of subjective experience and environmental karmic effects.

Nichiren envisioned this transformed world as a tangible outcome of faith and practice, though he rarely detailed its specific characteristics.

Nichiren taught that anyone who embraced the Lotus Sutra and had faith in it would enter the "pure land of Vulture Peak", associated with the Lotus Sutra's assembly in the air.

However, Nichiren did not regard this pure land as realm separate from this world.

Nichiren taught that all beings had the same capacity to attain Buddhahood.

Nichiren held that the Lotus Sutra teaches the equality of all beings.

Nichiren taught that neither social class nor gender were barriers to one's Buddhahood.

Nichiren was a charismatic leader who attracted many followers during both his missionary trips and his exiles.

Nichiren taught his followers that women were equally able to attain enlightenment.

Nichiren wrote to them often, sharing his rationale and strategies with them, openly urging them to share his conviction and struggles.

Nichiren claimed the precedent for shitei funi is a core theme of the Lotus Sutra, especially in chapters 21 and 22 where the Buddha entrusts the future propagation of the sutra to the gathered bodhisattvas.

The Institute of Nichiren Buddhist Studies at Rissho University is a major Japanese institution which focuses on Nichiren studies.

Nichiren has drawn less attention from Western scholars than other Japanese Buddhist figures, and he was intially stereotyped as intolerant or militant.

Nichiren's collected works in four volumes contains up to five hundred writings.

Nichiren kept a copy of the Lotus Sutra which he annotated profusely and has been published.

Nichiren's existing works number over 700 manuscripts in total, including transcriptions of orally delivered lectures, letters of remonstration and illustrations.

Collectively these letters demonstrate that Nichiren was a master of providing both comfort and challenge befitting the unique personalities and situations of each individual.

Nichiren incorporated several hundred of these anecdotes and took liberty to freely embellish some of them; a few of the stories he provided do not appear in other collections and could be original.

Nichiren used his letters as a means to inspire key supporters.

Against a backdrop of earlier Buddhist teachings that deny the possibility of enlightenment to women or reserve that possibility for life after death, Nichiren is highly sympathetic to women.