1.

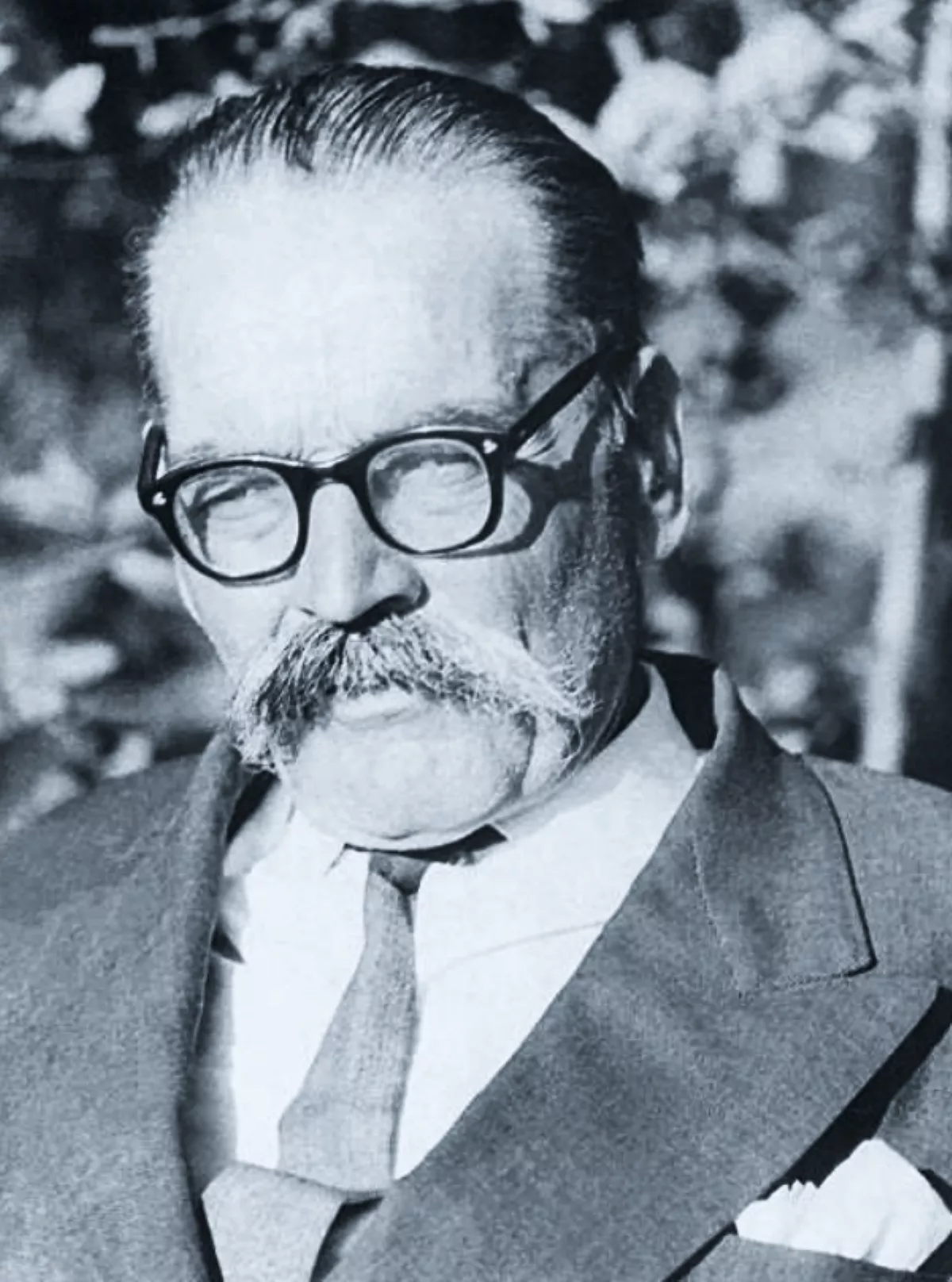

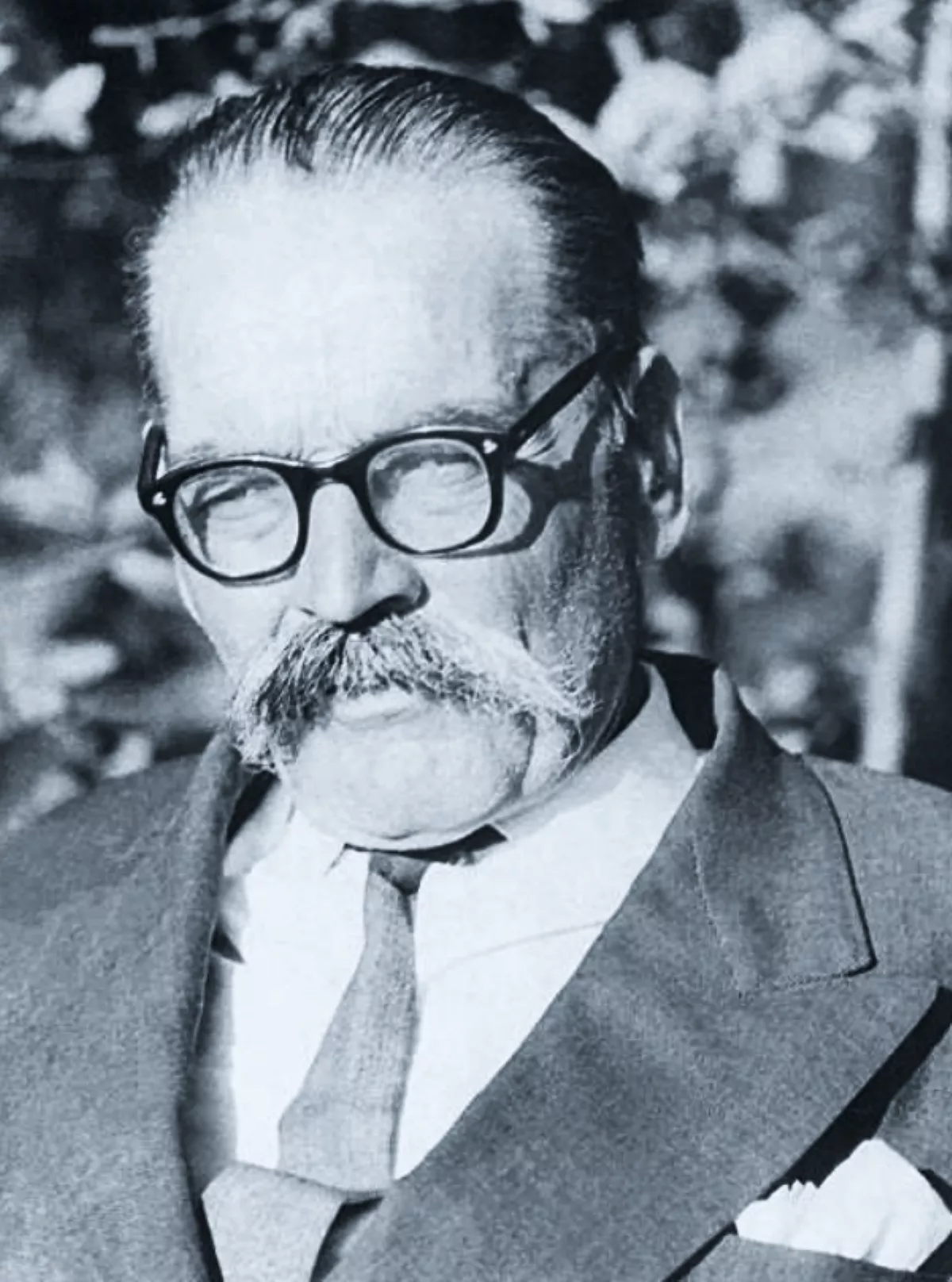

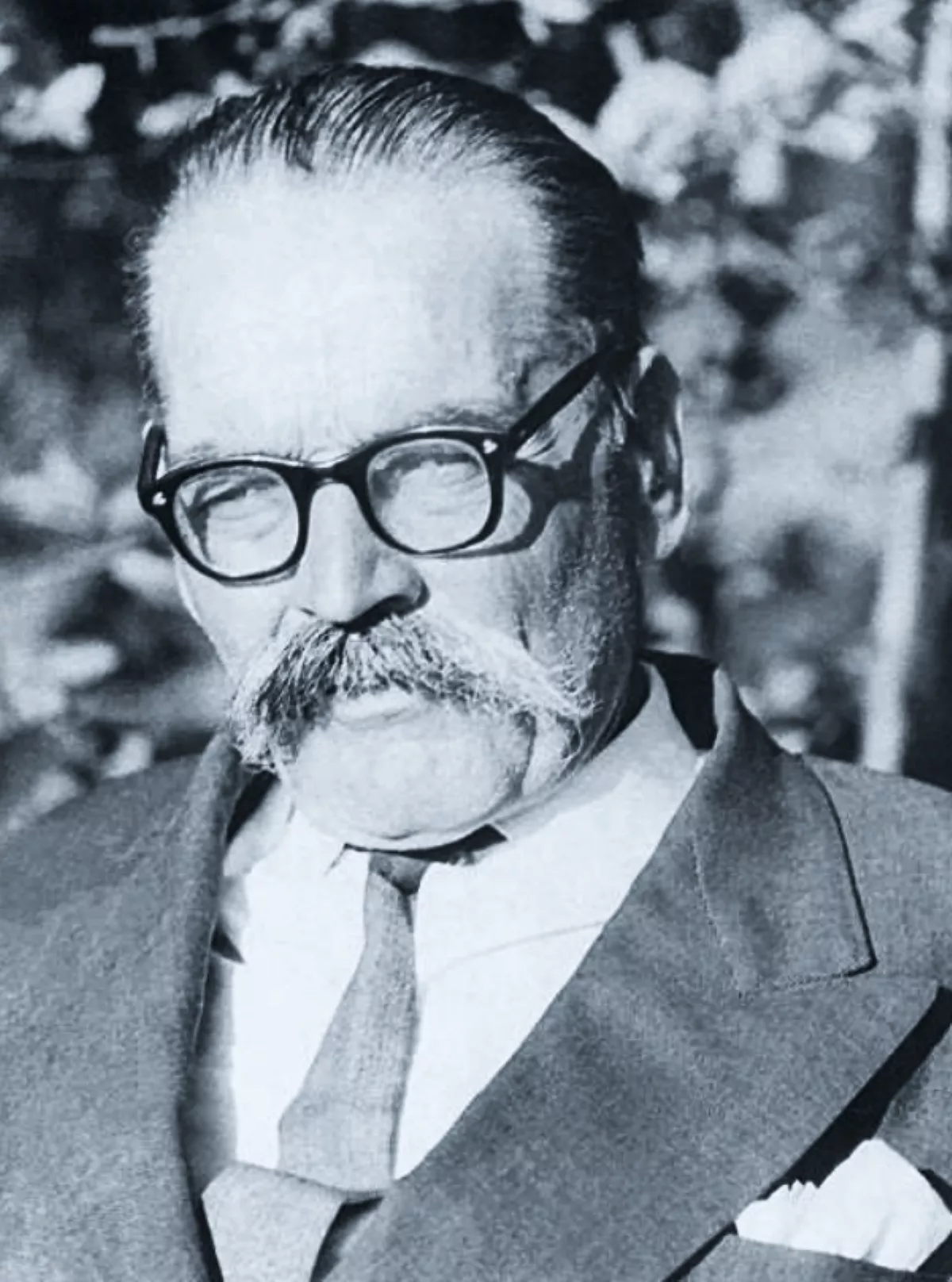

1. Petre Pandrea, pen name of Petre Ion Marcu, known as Petru Marcu Bals, was a Romanian social philosopher, lawyer, and political activist, noted as an essayist, journalist, and memoirist.

1.

1. Petre Pandrea, pen name of Petre Ion Marcu, known as Petru Marcu Bals, was a Romanian social philosopher, lawyer, and political activist, noted as an essayist, journalist, and memoirist.

Petre Pandrea riled up the cultural establishment of Greater Romania in 1928, when, with Ion Nestor and Sorin Pavel, he produced the "White Lily" manifesto.

In early 1938, while serving in the Assembly of Deputies, Petre Pandrea caused uproar by joining the far-right National Christian Party.

Petre Pandrea was himself arrested by Siguranta agents on several occasions, but not prosecuted by the regime.

Petre Pandrea provoked the communists, including his brother in law, by seeking fair treatment for prosecuted fascists and Peasantists; he drafted plans for Romania's "Helvetization" and integration with a larger Balkan Federation, both of which contrasted with the Soviet Union's regional agenda.

Petre Pandrea was held without trial at various facilities, including Ocnele Mari, for almost five years, returning to civilian life as a committed anti-communist and a penitent son of the Romanian Orthodox Church.

Unexpectedly reintegrated as a lawyer, Petre Pandrea again provoked the authorities, as well as church hierarchs, by agreeing to defend marginalized Christian communities, including the nuns of Vladimiresti.

Petre Pandrea was rearrested by the Securitate in 1958, leading to the discovery and confiscation of his secret memoirs, with their unflattering musings about the communists' real-life personas.

Petre Pandrea was selected for the final, least violent, experiment of re-education, and allowed to write controversial diaries detailing his experience.

Petre Pandrea was granted a rehabilitation months after his death; his ethnographer son Andrei fled abroad in 1979, and was sentenced to a prison term in absentia.

Petre Pandrea Marcu hailed from the ethnographic region of Oltenia, in what was back then the Kingdom of Romania.

Petre Pandrea was born on 26 June 1904, at Bals, to a middle-income peasant father, Ion Marcu, and his wife Ana.

Petre Pandrea allowed impoverished Romanies to settle on his land, and, during the peasants' revolt of 1907, personally intervened to reduce the damages on both sides.

Petre Pandrea described himself as an admirer of the 1821 Oltenian rebels, led into battle by Tudor Vladimirescu.

Petre Pandrea was generally welcoming of Jewish intellectuals, as long as they were Oltenian: he once described painter Medi Dinu, who was born in Valcea County, as a "superior Jewess"; he identified Vladimirescu's spirit in novelist Felix Aderca, celebrated by Pandrea as Romania's most important Jewish novelist.

From 1915 to 1922, Petre Pandrea was a student at Dealu Monastery high school, preparing for a career in the Land Forces.

Petre Pandrea was instead close to another schoolmate, Nicholas of Romania, the junior son of King Ferdinand I This friendship gave him his first glimpses of life at the Romanian court.

Petre Pandrea remained active in the press after that date, though some of his early contributions remain inscrutable.

Researchers are divided about its authorship: some see it as a hoax by Petre Pandrea, who presented it as composed by George Bacovia, while others agree that it was in fact a genuine Bacovian piece.

Ibraileanu, who had been impressed upon discovering that Petre Pandrea had talent, took his side, inviting him to move to Iasi, and adding him to the list of permanent contributors.

Petre Pandrea was however shy about his contributions, and for the next forty years prevented anyone from publishing his photograph.

Petre Pandrea was accepted by the University of Bucharest, where he heard lectures by Ionescu, Dimitrie Gusti, and Vasile Parvan, with the latter becoming his lifelong model.

Petre Pandrea then took courses at Heidelberg University and Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, and from 1928 or 1929 was employed as a press attache by the Romanian legation in Berlin.

Petre Pandrea was reportedly an "honorary correspondent" of the right-wing Bucharest daily, Curentul.

Petre Pandrea traveled about, attending lectures at the Universities of Paris, Vienna, Rome, Prague, and Budapest.

Briefly involved in historical research, Petre Pandrea traced down and publish a medieval manuscript by Albertus Schendl, detaling the life and times of Stephen the Great.

Petre Pandrea's effort was rewarded by Iorga, who was serving as Prime Minister of Romania, and who granted him 1,000 Reichsmark.

Petre Pandrea kept informed about cultural events in Greater Romania, initially declaring himself opposed to the rationalist, left-liberal, Francophile bent that had emerged as dominant in the 1920s.

Petre Pandrea was disgusted by literary theorists such as Eugen Lovinescu and Paul Zarifopol, writing them off as unoriginal, the "anemic offshoots" of Jules Lemaitre and Emile Faguet.

Similarly, historian Radu Ioanid proposes that Petre Pandrea had been genuinely transformed by Crainic, and further influenced by Charles Maurras, in fully rejecting the tenets of Romanian liberalism.

The latter was especially derisive of Petre Pandrea's religiousness, calling him out as a Romanian "Rasputin".

Petre Pandrea was offered initiation into the Freemasonry, but rejected it on his father's advice.

Stanomir, who equates this stance with atheism, notes that Petre Pandrea was rare among Romanian interwar figures in his voluntary embrace of Marxism, albeit as an "unfaithful and impure" disciple.

Petre Pandrea is known for his contradictory status, as one who, with his resounding gestures, had crossed over from the right to the radical left in 1931.

Petre Pandrea's analysis featured a derisive quote from Nae Ionescu, who had defined nationhood as a "community of love and of life", adding to it his own comment: A se slabi.

Petre Pandrea endorsed the group's front organization, called Peasant Workers' Bloc.

Petre Pandrea, who responded through columns in Dreptatea, was upset that his adversary still viewed him as a disciple; he professed his belief that Ionescu's Orthodox-supremacist ideology was aping political Catholicism, adding only a touch of "Byzantinism".

On his trips back to Bucharest, Petre Pandrea carried Dimitrov's clandestine propaganda, which ultimately reached Bulgaria.

Petre Pandrea was in any case kept under watch by the old-regime secret police, called Siguranta, as one of the intellectuals who seemed to be serving the communist agenda.

Petre Pandrea once confessed that Nazi racial theories had affected his own career choices, in that he decided to quit Germany for good after a native student had called him a "filthy Balkanoid" to his face.

The civil ceremony took place in April 1932, just before Petre Pandrea fulfilled his service in the Land Forces, with an infantry regiment stationed at Caracal; their son, Andrei Dumitru Marcu, was born in March 1936.

Petre Pandrea was a full-time reporter at Adevarul, with his domicile registered as 2 Alba Street.

Petre Pandrea consolidated his left-wing affiliations with "vitriolic" articles in Adevarul, Dimineata, Azi and Bluze Albastre, using pseudonyms such as Petre Albota, Gaius, Petre Dragu, Dr Petru Ionica, Dr X, and Dr P, as well as his consecrated pen name.

Petre Pandrea reportedly enjoyed "extraordinary success" with this book, and continued to write about the topic, enough to have been able to put together a second volume.

Petre Pandrea was co-opted to serve on the editorial team at Cuvantul Liber.

Petre Pandrea announced that he was working on a "social novel", Tractorul, fragments of which were published by Vremea daily in October 1932.

Petre Pandrea penned a treatise on economic doctrines as applied to the Great Depression in Romania.

In October 1934, Petre Pandrea was among the founding members of a Bucharest branch of Amicii URSS society, supporting a detente between Romania and the Soviet Union.

Petre Pandrea was among those attending the funeral, which was organized by an Iron Guard dissidence, the "Crusade of Romanianism".

Petre Pandrea himself was greatly alarmed by the Moscow trials, and especially by the public humiliation of Nikolai Bukharin and Christian Rakovsky, whom he admired.

The article was signed by Petre Pandrea, but, according to communist militant Stefan Voicu, it was entirely authored by Patrascanu.

Petre Pandrea was similarly involved in supporting the communist academic Petre Constantinescu-Iasi, who was facing trial at Chisinau.

Petre Pandrea soon attracted negative attention from the Iron Guard's daily, Porunca Vremii, which described him as a "communist dandy"; a Guardist ideologue, Vasile Marin, listed him among the enemies of the Romanian nation.

In June 1936, Petre Pandrea had returned to Caracal, where he inaugurated a PNT "school for propagandists".

Petre Pandrea's rival responded in a Vremea article during September 1934.

Petre Pandrea explained himself as motivated by his enduring belief in a "national, monarchic, peasant State", which the PNT leader Iuliu Maniu had betrayed.

Petre Pandrea was concurrently expelled from the PNT, who noted that he had formally registered with the PNC.

Petre Pandrea was privately disgusted by this political change, and especially infuriated by Carol's co-operation with the Orthodox Patriarch, Miron Cristea, since it had destroyed the Church's good reputation.

Petre Pandrea has appeared at trials of repressed communists, and cited the new legal provisions to their advantage.

Also in 1938, Petre Pandrea published his translation of Aurel Popovici's Vereinigten Staaten von Gross-Osterreich.

Petre Pandrea supported the notion that Popovici had wanted to include Romania-proper into a regional union, formed around the Habsburg monarchy.

Historian Theodor Rascanu argued that, in order to highlight such claims, Petre Pandrea had falsified portions of Popovici's text, replacing the word "Bukovina" with "Romania".

Petre Pandrea especially deplored Nae Ionescu's death, and circulated rumors according to which his erstwhile mentor had been discreetly killed on Carol's orders, either with poisoned cigarettes or a lethal injection.

The Guardists settled their scores with old-regime figures, including Iorga; according to Petre Pandrea, Iorga was responsible for his own death, since his brand of nationalism and antisemitism had produced the Guard.

Petre Pandrea blamed this debacle on Ralea, who had arranged the defense, and on Istrate Micescu, who joined the team of attorneys only to betray them.

Petre Pandrea again tested official dogmas by acting as a public defender for the imprisoned Guardists.

Petre Pandrea was again friends with the now-captive Gyr, describing him as a fellow "Mandarin" of Romanian culture.

Petre Pandrea still published a number of brochures on legal topics, commissioning a printing press manned by the inmates of Vacaresti Prison.

Petre Pandrea visited frequently with Patrascanu, who had been placed under house arrest at his villa in Poiana Tapului, on the Prahova Valley.

Petre Pandrea brought him virtually all the books that Patrascanu used in writing his own sociological tracts.

Petre Pandrea confessed that he financed himself by overcharging his other clients, who were mainly Oltenian traders, facing trial in Bucharest for "economic sabotage and price gouging".

Petre Pandrea claimed that in early 1941, using funds extorted from a "tanner out of Calafat", he established the Meridian group, formally led by Alexandru Balaci, Mihnea Gheorghiu, and Tiberiu Iliescu, and disguising itself as a "literary society".

When I first met [Petre Pandrea] he was on one of his regular visits to Craiova.

Petre Pandrea always had multicolored girl typists by his side.

Petre Pandrea was vaguely interested in the lawsuits, and cared more about cultural affairs.

Petre Pandrea was all smiles, perky, original, and always on his way to Bals, his hometown.

Petre Pandrea was all wasteful, except when it came to his immediate interests.

Petre Pandrea had this funny way of not adhering to anything.

Petre Pandrea ensured the legal defense for communist militant Francisc Panet and his wife Lili, but was unable to obtain that they be spared execution.

Petre Pandrea successfully argued that simply holding out gold in one's possession was not a breach of Antonescu's legislation regarding "sabotage".

Petre Pandrea joined the Romanian Society for Friendship with the Soviet Union and its Sociological Section, whose chairman was Sabin Manuila.

Petre Pandrea contributed two volumes of Portrete si controverse, seen by Ornea as "charmingly enticing", "learned without being doctoral".

Also here, Petre Pandrea completed his Marxist study of Romanian nationalism, and of antisemitism in general, describing both as bygone tools for distracting the proletariat.

Petre Pandrea expanded on "localism" with a 1946 volume, Pomul vietii, which is a philosophical diary of the two previous years.

Petre Pandrea was additionally interviewed by Ion Biberi for a 1945 book on "the world of tomorrow", which saw him elaborating his ideas on the inevitable advent of a "socialist morality", but his discussing poetics and the typology of Romanian poets.

Petre Pandrea takes his reader on an adventure, with every page as a new act in this total spectacle.

Petre Pandrea had parted ways with his in-laws, and, upon being confronted by the "Tamadau Affair", decided to act as a public defender for his National Peasantist colleagues, including Ghita Popp.

Petre Pandrea was by then unabashedly anti-Stalinist, and increasingly anti-Soviet, arguing that the "dictatorship of the proletariat", an inherently "romantic" notion of limited use, had been transformed into a justification for permanent totalitarian control.

Petre Pandrea soon produced designs for Romania's "Helvetization" within a larger bloc of Balkan states, alongside Yugoslavia and Bulgaria.

Petre Pandrea spent four years and seven months in jail, under circumstances described by Moisa as "dreadful".

Petre Pandrea was held at Aiud, and eventually moved to Ocnele Mari.

Petre Pandrea claimed that he been dropped out of the Patrascanu trial because of Dimitrov, who had asked about his friend, even prompting the authorities to release him for a short interval.

Petre Pandrea tried to help a colleague, Savel Radulescu, who was being framed for conspiracy against the state, with advise on how to best organize his legal defense.

Petre Pandrea describes in some detail the living conditions, noting that, after months and years of malnutrition, the entire prison population struggled with vitamin deficiency, periodontal disease, and oliguria, and fed itself on linden leaves to prevent additional damage.

Petre Pandrea was operated on for dacryocystitis, but after his eyes had been permanently damaged.

Petre Pandrea could talk back, mocking his interrogators for having "licked Ana Pauker in her cunt".

Petre Pandrea's father had never seen him during the interval, and could not recognize him when they eventually reunited; in their first conversation, they discussed Andrei's clandestine attempts to finish school.

Petre Pandrea was reactivated as a translator by Biblioteca pentru toti, and in 1956 produced a version of Dimitrie Cantemir's geographical tract, Descriptio Moldaviae.

Philologist Dimitrie Florea-Rariste criticized the choice, in particular since Petre Pandrea had worked from a German version rather than from the Neo-Latin original, resulting in various errors and inconsistencies.

Petre Pandrea was eventually, and unusually, allowed to return to the legal profession.

Petre Pandrea took pride in his subsequent activity, which involved appearing in "tens of rayon-and-region-level tribunals".

Petre Pandrea was involved in the legal representation for the mainstream monks of Ploscuteni and for the unrecognized Lipovan Church.

Petre Pandrea was rearrested by the Securitate on 23 October 1958.

Petre Pandrea was eventually allowed to work as a country doctor in Boisoara.

Petre Pandrea was moved to Jilava Prison in mid-1959, and, by his own account, was again beaten up, in a variety of ways and for no discernible reason.

Petre Pandrea experienced hunger pangs throughout the day, continuously so from 1959 to 1962.

Petre Pandrea later wrote about these as a special form of gastritis, but argued that the diet had its advantages, since it induced deep restful sleep in the victim.

At around that time, Petre Pandrea witnessed the death of a fellow inmate, George Manu, who had presided upon a moderate but uncooperative faction of the Iron Guard.

Petre Pandrea's account was challenged by several other inmates, who contrarily reported that Manu had been passively euthanized by prison guards after having refused to undergo re-education.

Petre Pandrea managed to obtain access to writing tools, and began work on an autobiographical novel, called Tragedia de la Margaritesti, totaling some 200 pages in its manuscript.

Petre Pandrea was only released in spring 1964, after a general amnesty of all political prisoners, and had arrived at Poiana Tapului by 1 June.

Petre Pandrea was however granted a small state pension, and progressively allowed to reconnect with his peers in the literary world.

Eugen Barbu, who was putting out Luceafarul in Bucharest, recalls being visited by "Petre Pandrea, morally exhausted by some great injustice and seeking typographic space for reuniting himself with a public that had just about forgotten him".

Petre Pandrea was living at 96 Sandu Aldea Street, in northern Bucharest, but vacationing with his daughter at Poiana Tapului and in Peris.

Petre Pandrea was meanwhile turning to full-blown conservatism, consciously modeled on 19th-century Junimism; as noted by Stanomir, his manuscript memoirs fold back on anti-rationalism, reconnecting Pandrea with his first-ever mentor, Nae Ionescu.

Petre Pandrea declared himself irreconcilable with the new justice-system, which drove lawyers into a "fraternization with the prosecutors", allowing them to plead against their own clients.

Petre Pandrea made his children promise that they would only bury him in "my tiny homeland" of Oltenia.

Petre Pandrea made a return trip to Craiova in November 1967, but only managed to meet Nicolaescu-Plopsor.

Petre Pandrea died in Bucharest on 8 July 1968, shortly after having turned 64.

The dying Petre Pandrea had sent Rusu one of his final manuscripts, which was a sentimental record of his encounters with Garabet Ibraileanu.

In late 1968, Ceausescu and the PCR's permanent presidium issued a resolution that posthumously rehabilitated "Marcu Petre Pandrea", noting that the testimonies against him had been collected from unreliable witnesses, including members of the Iron Guard, and that some of them had since recanted.

Also that year, the official Marxist scholar Miron Constantinescu, whom Petre Pandrea had regarded as an uneducated tool of Pauker's "genocidal" faction, published an overview of recoverable sociology.

Crohmalniceanu's short memoir of his encounters with Petre Pandrea was put out by Romania Literara in July 1978.

An audio recording of Petre Pandrea reading from his Brancusi-themed book had been aired by the Romanian Radio Broadcasting Company in July 1979.

At the time of his father's death, Andrei Petre Pandrea was a lecturer of literary history at Stefan Gheorghiu Academy and an adviser on rural medicine for the Romanian Ministry of Health.

Petre Pandrea's books were refused by several publishing houses, which had continued to publish his father's works.

Petre Pandrea was joined in Paris by his elderly mother, and by his sister.

Andrei Petre Pandrea only made brief returns to Romania after the Romanian Revolution of 1989, when the peasants of Boisoara voted to award him a plot of land.