1.

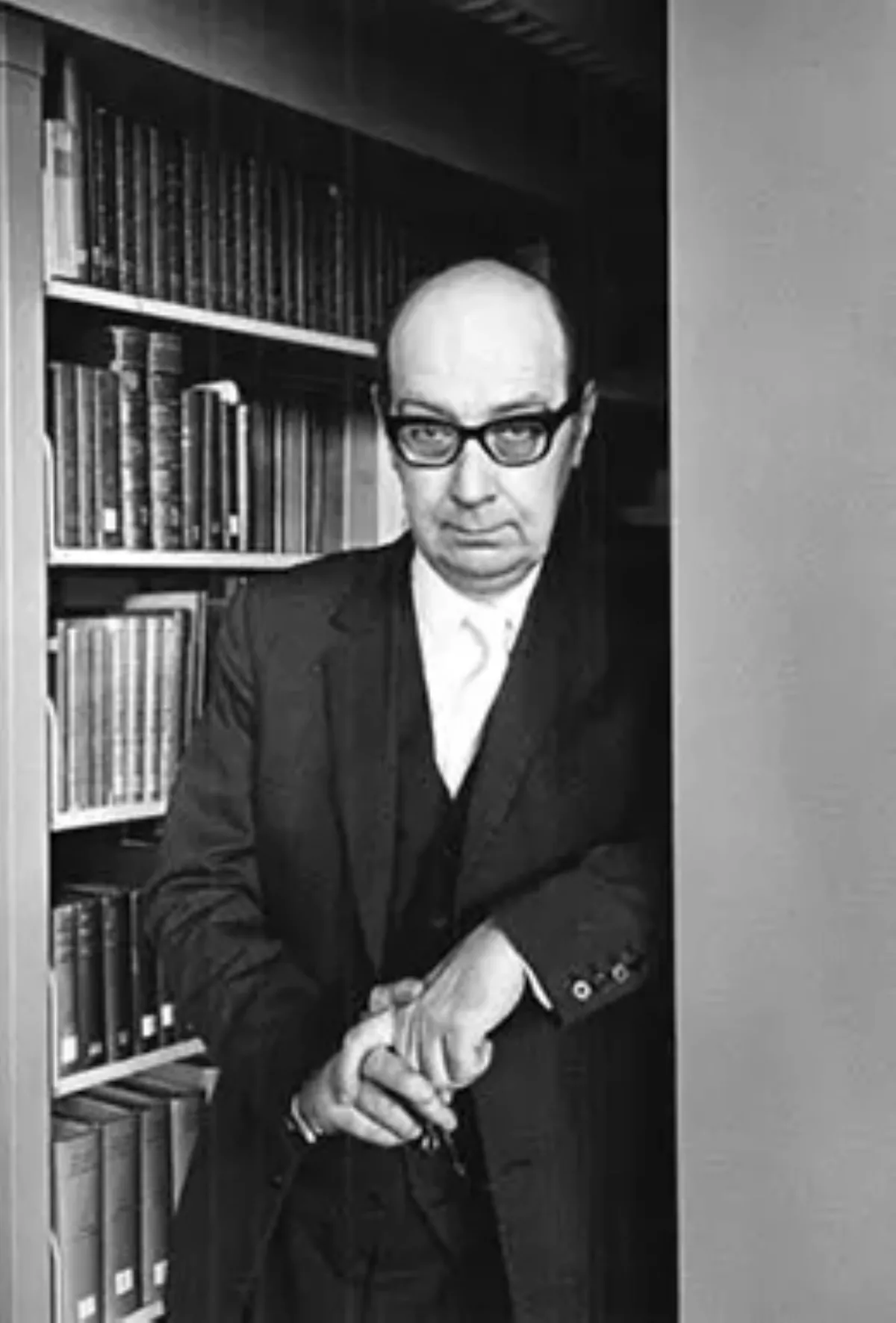

1. Philip Arthur Larkin was an English poet, novelist, and librarian.

1.

1. Philip Arthur Larkin was an English poet, novelist, and librarian.

Philip Larkin came to prominence in 1955 with the publication of his second collection of poems, The Less Deceived, followed by The Whitsun Weddings and High Windows.

Philip Larkin was offered, but declined, the position of Poet Laureate in 1984, following the death of Sir John Betjeman.

Philip Larkin's poems are marked by what Andrew Motion calls "a very English, glum accuracy" about emotions, places, and relationships, and what Donald Davie described as "lowered sights and diminished expectations".

Lisa Jardine called him a "casual, habitual racist, and an easy misogynist", but the academic John Osborne argued in 2008 that "the worst that anyone has discovered about Philip Larkin are some crass letters and a taste for porn softer than what passes for mainstream entertainment".

On 2 December 2016, the 31st anniversary of his death, a floor stone memorial for Philip Larkin was unveiled at Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey.

Philip Larkin was born on 9 August 1922 at 2 Poultney Road, Radford, Coventry, the only son and younger child of Sydney Larkin and his wife Eva Emily, daughter of first-class excise officer William James Day.

Sydney Philip Larkin's family originated in Kent, but had lived since at least the eighteenth century at Lichfield, Staffordshire, where they worked first as tailors, then as coach-builders and shoe-makers.

Philip Larkin's family lived in the district of Radford, Coventry, until Philip Larkin was five years old, before moving to a large three-storey middle-class house complete with servants' quarters near Coventry railway station and King Henry VIII School, in Manor Road.

Philip Larkin fared quite poorly when he sat his School Certificate exam at the age of 16.

Philip Larkin began at Oxford University in October 1940, a year after the outbreak of the Second World War.

In 1943 Philip Larkin was appointed librarian of the public library in Wellington, Shropshire.

Six weeks after his father's death from cancer in March 1948, Philip Larkin proposed to Ruth, and that summer the couple spent their annual holiday touring Hardy country.

In June 1950 Philip Larkin was appointed sub-librarian at The Queen's University of Belfast, a post he took up that September.

Philip Larkin spent five years in Belfast, which appear to have been the most contented of his life.

From 1951 onwards Philip Larkin holidayed with Jones in various locations around the British Isles.

In 1955 Philip Larkin became University Librarian at the University of Hull, a post he held until his death.

When Philip Larkin took up his appointment there, the plans for a new university library were already far advanced.

Philip Larkin made a great effort in just a few months to familiarize himself with them before they were placed before the University Grants Committee; he suggested a number of emendations, some major and structural, all of which were adopted.

Ten years after the new library's completion, Philip Larkin computerized records for the entire library stock, making it the first library in Europe to install a Geac computer system, an automated online circulation system.

Richard Goodman wrote that Philip Larkin excelled as an administrator, committee man and arbitrator.

From 1957 until his death, Philip Larkin's secretary was Betty Mackereth.

All access to him by his colleagues was through her, and she came to know as much about Philip Larkin's compartmentalized life as anyone.

Philip Larkin's poem "Show Saturday" is a description of the 1973 Bellingham show in the North Tyne valley.

In 1964, following the publication of The Whitsun Weddings, Philip Larkin was the subject of an edition of the arts programme Monitor, directed by Patrick Garland.

In 1968, Philip Larkin was offered the OBE, which he declined.

Philip Larkin was awarded a Visiting Fellowship at All Souls College, Oxford, for two academic terms, allowing him to consult Oxford's Bodleian Library, a copyright library.

Philip Larkin was a major contributor to the re-evaluation of the poetry of Thomas Hardy, which, in comparison to his novels, had been overlooked; in Philip Larkin's "idiosyncratic" and "controversial" anthology, Hardy was the poet most generously represented.

In 1971, Philip Larkin regained contact with his schoolfriend Colin Gunner, who had led a picaresque life.

Shortly after splitting up with Maeve Brennan in August 1973, Larkin attended W H Auden's memorial service at Christ Church, Oxford, with Monica Jones as his official partner.

In 1976, Philip Larkin was the guest of Roy Plomley on BBC's Desert Island Discs.

At the memorial service for John Betjeman, who died in July 1984, Philip Larkin was asked if he would accept the post of Poet Laureate.

Philip Larkin declined, not least because he felt he had long since ceased to be a writer of poetry in a meaningful sense.

Philip Larkin died four days later, on 2 December 1985, at the age of 63, and was buried at Cottingham municipal cemetery near Hull.

Philip Larkin had asked on his deathbed that his diaries be destroyed.

Philip Larkin's will was found to be contradictory regarding his other private papers and unpublished work; legal advice left the issue to the discretion of his literary executors, who decided the material should not be destroyed.

Philip Larkin is commemorated with a green plaque on The Avenues, Kingston upon Hull.

From his mid-teens, Larkin "wrote ceaselessly", producing both poetry, initially modelled on Eliot and W H Auden, and fiction: he wrote five full-length novels, each of which he destroyed shortly after their completion.

Philip Larkin developed a pseudonymous alter ego in this period for his prose: Brunette Coleman.

Immediately after completing Jill, Philip Larkin started work on the novel A Girl in Winter, completing it in 1945.

Poems by Philip Larkin were included in a 1953 PEN Anthology that featured poems by Amis and Robert Conquest, and Philip Larkin was seen to be a part of this grouping.

In 1951, Philip Larkin compiled a collection called XX Poems which he had privately printed in a run of just 100 copies.

In 1963, Faber and Faber reissued Jill, with the addition of a long introduction by Philip Larkin that included much information about his time at Oxford University and his friendship with Kingsley Amis.

In 1972, Philip Larkin wrote the oft-quoted "Going, Going", a poem which expresses a romantic fatalism in its view of England that was typical of his later years.

Philip Larkin's style is bound up with his recurring themes and subjects, which include death and fatalism, as in his final major poem "Aubade".

Philip Larkin was a critic of modernism in contemporary art and literature.

Philip Larkin's scepticism is at its most nuanced and illuminating in Required Writing, a collection of his book reviews and essays, and at its most inflamed and polemical in his introduction to his collected jazz reviews, All What Jazz, drawn from the 126 record-review columns he wrote for The Daily Telegraph between 1961 and 1971, which contains an attack on modern jazz that widens into a wholesale critique of modernism in the arts.

Philip Larkin acquired a reputation as an enemy of modernism, but recent critical assessments of Philip Larkin's writings have identified them as possessing some modernist characteristics.

Fraser, referring to Philip Larkin's perceived association with The Movement felt that Philip Larkin exemplified "everything that is good in this 'new movement' and none of its faults".

In 1980, Neil Powell wrote: "It is probably fair to say that Philip Larkin is less highly regarded in academic circles than either Thom Gunn or Donald Davie".

Robert Sheppard asserts: "It is by general consent that the work of Philip Larkin is taken to be exemplary".

Chatterjee's view of Philip Larkin is grounded in a detailed analysis of his poetic style.

For Chatterjee, Philip Larkin's poetry responds strongly to changing "economic, socio-political, literary and cultural factors".

The view that Philip Larkin is not a nihilist or pessimist, but actually displays optimism in his works, is certainly not universally endorsed, but Chatterjee's study suggests the degree to which old stereotypes of Philip Larkin are now being transcended.

The debate about Philip Larkin is summed up by Matthew Johnson, who observes that in most evaluations of Philip Larkin "one is not really discussing the man, but actually reading a coded and implicit discussion of the supposed values of 'Englishness' that he is held to represent".

The letters and Motion's biography fuelled further assessments of this kind, such as Lisa Jardine's comment in The Guardian that "The Britishness of Philip Larkin's poetry carries a baggage of attitudes which the Selected Letters now make explicit".

In 2003, almost two decades after his death, Philip Larkin was chosen as "the nation's best-loved poet" in a survey by the Poetry Book Society, and in 2008 The Times named Philip Larkin as the greatest British post-war writer.

Media interest in Philip Larkin has increased in the twenty-first century.

In 1959, the Marvell Press published Listen presents Philip Larkin reading The Less Deceived, an LP record on which Larkin recites all the poems from The Less Deceived in the order they appear in the printed volume.

Once again the poems are read in the order in which they appear in the printed volume, but with Philip Larkin including introductory remarks to many of the poems.

In 1980, Philip Larkin was invited by the Poets' Audio Center, Washington, to record a selection of poems from the full range of his poetic output for publication on a Watershed Foundation cassette tape.

In contrast to the number of audio recordings of Philip Larkin reading his own work, there are very few appearances by Philip Larkin on television.

The only programme in which he agreed to be filmed taking part is Down Cemetery Road, from the BBC Monitor series, in which Philip Larkin was interviewed by John Betjeman.

In 1981, Philip Larkin was part of a group of poets who surprised John Betjeman on his seventy-fifth birthday by turning up on his doorstep with gifts and greetings.

In 1982, as part of the celebrations for his sixtieth birthday, Philip Larkin was the subject of The South Bank Show.

The Philip Larkin Society is a charitable organization dedicated to preserving the memory and works of Philip Larkin.

The unveiling was accompanied by Nathaniel Seaman's Fanfare for Philip Larkin, composed for the occasion.

Five plaques containing Philip Larkin's poems were added to the floor near the statue in 2011.

In June 2015, it was announced that Philip Larkin would be honoured with a floor stone memorial at Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey.