1.

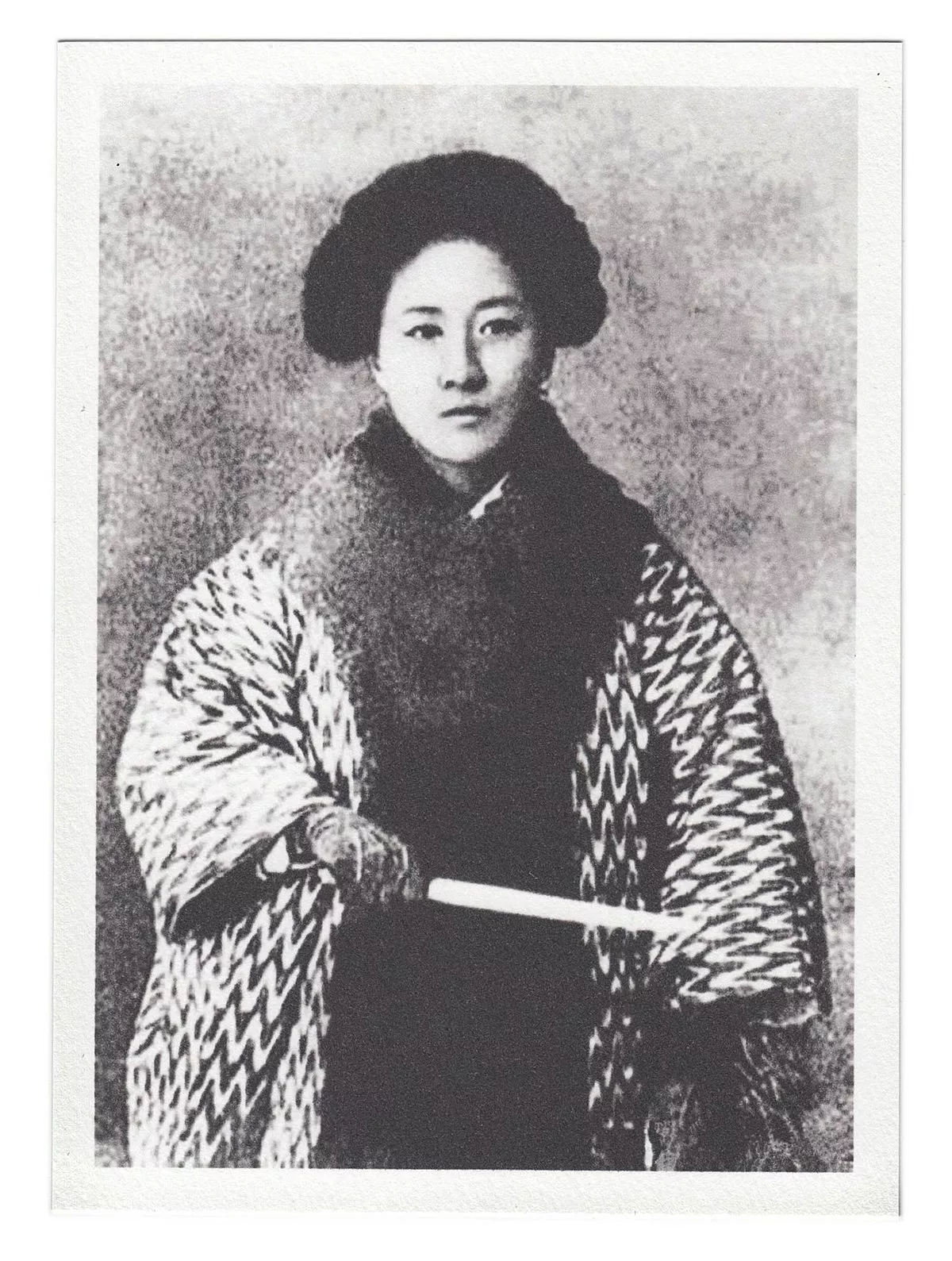

1. Qiu Jin was a Chinese revolutionary, feminist, and writer.

1.

1. Qiu Jin was a Chinese revolutionary, feminist, and writer.

Qiu Jin's grandfather worked in the Xiamen city government and was responsible for the city's defense.

Zhejiang province was famous for female education, and Qiu Jin had support from her family when she was young to pursue her educational interests.

Qiu Jin's father, Qiu Shounan, was a government official and her mother came from a distinguished literati-official family.

Qiu Jin was one of these elites that got the chance to study overseas.

Qiu Jin had her feet bound and began writing poetry at an early age.

Qiu Jin's father arranged her marriage to Wang Tingjun, the youngest son of a wealthy merchant in Hunan province.

Qiu Jin did not get along well with her husband, as her husband only cared about enjoying himself.

Unhappy in her marriage, Qiu Jin sought personal and intellectual fulfillment by obtaining education in Japan.

Qiu Jin was one of the girls who got the chance to study overseas as these opportunities were only given to the children of higher social class.

Qiu Jin initially entered a Japanese language school in Surugadai, but later transferred to the Girls' Practical School in Kojimachi, run by Shimoda Utako.

Qiu Jin was very fond of martial arts, and she was known by her acquaintances for wearing Western male dress and for her nationalist, anti-Manchu ideology.

Qiu Jin joined the anti-Qing society Guangfuhui, led by Cai Yuanpei, which in 1905 joined with a variety of overseas Chinese revolutionary groups to form the Tongmenghui, led by Sun Yat-sen.

In one issue, Qiu Jin wrote A Respectful Proclamation to China's 200 Million Women Comrades, a manifesto within which she lamented the problems caused by bound feet and oppressive marriages.

Qiu Jin joined forces with her cousin Xu Xilin and together they worked to unite many secret revolutionary societies to work together for the overthrow of the Qing dynasty.

Between 1905 and 1907, Qiu Jin was writing a novel called Stones of the Jingwei Bird in traditional ballad form, a type of literature often composed by women for women audiences.

Qiu Jin was known as an eloquent orator who spoke out for women's rights, such as the freedom to marry, freedom of education, and abolishment of the practice of foot binding.

Qiu Jin was tortured but refused to admit her involvement in the plot.

Qiu Jin's last written words, her death poem, uses the literal meaning of her name, Autumn Gem, to lament of the failed revolution that she would never see take place:.

Qing officials soon ordered for her tomb to be razed, but Qiu Jin's brother managed to retrieve her body in time.

Qiu Jin's death was a major topic in late Qing era newspapers.

Newspapers with a range of political perspectives described her treatment as unjust and compared her to a contemporary Dou E These media discussions of Qiu focused on her mistreatment in the justice system of a corrupt government; while they acknowledged her advocacy for women, they denied her revolutionary activities.

Qiu Jin inspired literary works in the years immediately following her death.

The Shenzhou Daily's serialized fiction Resurrection at Xuanting depicts Qiu Jin being revived under the name Xia Yu.

Qiu Jin was posthumously immortalized in the Republic of China's popular consciousness and literature.

Nationalist era plays written about Qiu Jin include Xia Yan's The Spirit of Freedom and Yan Yiyan's Qiu Jin.

One film, simply titled Qiu Jin, was released in 1983 and directed by Xie Jin.

Qiu Jin is briefly shown in the beginning of 1911, being led to the execution ground to be beheaded.

Qiu Jin's writing reflects an exceptional education in classical literature, and she writes traditional poetry.

Qiu Jin composes verse with a wide range of metaphors and allusions that mix classical mythology with revolutionary rhetoric.