1.

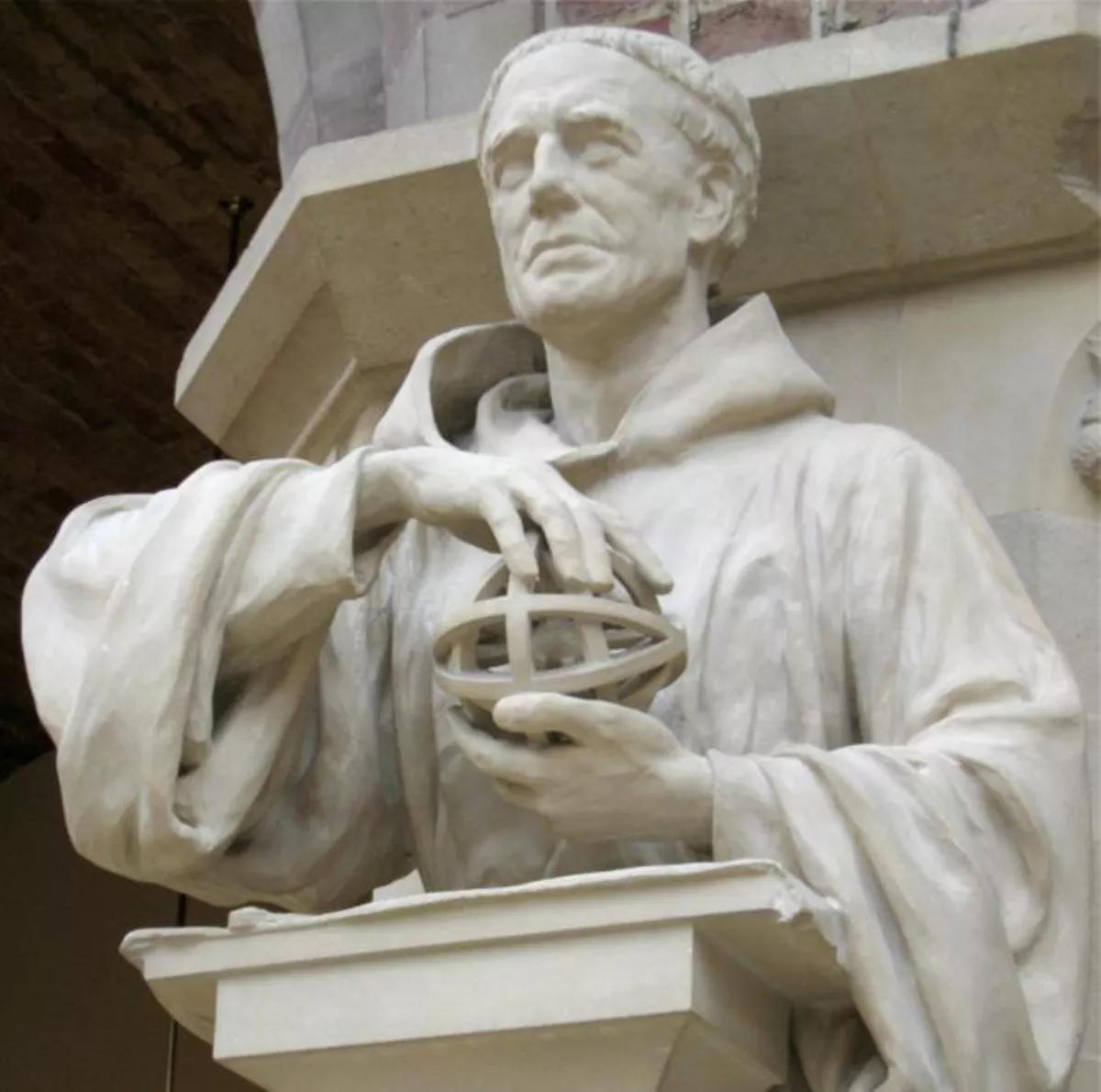

1. Intertwining his Catholic faith with scientific thinking, Roger Bacon is considered one of the greatest polymaths of the medieval period.

1.

1. Intertwining his Catholic faith with scientific thinking, Roger Bacon is considered one of the greatest polymaths of the medieval period.

Roger Bacon is credited as one of the earliest European advocates of the modern scientific method, along with his teacher Robert Grosseteste.

Roger Bacon discovered the importance of empirical testing when the results he obtained were different from those that would have been predicted by Aristotle.

Roger Bacon was partially responsible for a revision of the medieval university curriculum, which saw the addition of optics to the traditional.

Roger Bacon was born in Ilchester in Somerset, England, in the early 13th century.

Roger Bacon's birth is sometimes narrowed down to 1210,1213 or 1214,1215 or 1220.

The latest dates assume this referred to the alphabet itself, but elsewhere in the it is clear that Roger Bacon uses the term to refer to rudimentary studies, the trivium or quadrivium that formed the medieval curriculum.

Roger Bacon seems to have studied most of the known Greek and Arabic works on optics.

Roger Bacon was likely kept at constant menial tasks to limit his time for contemplation and came to view his treatment as an enforced absence from scholarly life.

In 1267 or '68, Roger Bacon sent the Pope his, which presented his views on how to incorporate Aristotelian logic and science into a new theology, supporting Grosseteste's text-based approach against the "sentence method" then fashionable.

The entire process has been called "one of the most remarkable single efforts of literary productivity", with Roger Bacon composing referenced works of around a million words in about a year.

Pope Clement died in 1268 and Roger Bacon lost his protector.

Some time within the next two years, Roger Bacon was apparently imprisoned or placed under house arrest.

Sometime after 1278, Roger Bacon returned to the Franciscan House at Oxford, where he continued his studies and is presumed to have spent most of the remainder of his life.

Roger Bacon seems to have died shortly afterwards and been buried at Oxford.

Roger Bacon argued that, rather than training to debate minor philosophical distinctions, theologians should focus their attention primarily on the Bible itself, learning the languages of its original sources thoroughly.

Roger Bacon was fluent in several of these languages and was able to note and bemoan several corruptions of scripture, and of the works of the Greek philosophers that had been mistranslated or misinterpreted by scholars working in Latin.

Roger Bacon argued for the education of theologians in science and its addition to the medieval curriculum.

Roger Bacon's arguments supporting the idea that dry land formed the larger proportion of the globe were apparently similar to those which later guided Columbus.

In Part I of the Opus Majus Roger Bacon recognises some philosophers as the Sapientes, or gifted few, and saw their knowledge in philosophy and theology as superior to the vulgus philosophantium, or common herd of philosophers.

Roger Bacon held Islamic thinkers between 1210 and 1265 in especially high regard calling them "both philosophers and sacred writers" and defended the integration of philosophy from apostate philosopher of the Islamic world into Christian learning.

In Part IV of the, Roger Bacon proposed a calendrical reform similar to the later system introduced in 1582 under Pope Gregory XIII.

Roger Bacon charged that this meant the computation of Easter had shifted forward by 9 days since the First Council of Nicaea in 325.

In Part V of the, Roger Bacon discusses physiology of eyesight and the anatomy of the eye and the brain, considering light, distance, position, and size, direct and reflected vision, refraction, mirrors, and lenses.

Roger Bacon's treatment was primarily oriented by the Latin translation of Alhazen's Book of Optics.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Henry William Lovett Hime of the Royal Artillery published the theory that Roger Bacon's contained a cryptogram giving a recipe for the gunpowder he witnessed.

Roger Bacon attributed the Secret of Secrets, the Islamic "Mirror of Princes", to Aristotle, thinking that he had composed it for Alexander the Great.

Roger Bacon produced an edition of Philip of Tripoli's Latin translation, complete with his own introduction and notes; and his writings of the 1260s and 1270s cite it far more than his contemporaries did.

Roger Bacon has been credited with a number of alchemical texts.

The Letter on the Secret Workings of Art and Nature and on the Vanity of Magic, known as On the Wonderful Powers of Art and Nature, a likely-forged letter to an unknown "William of Paris," dismisses practices such as necromancy but contains most of the alchemical formulae attributed to Roger Bacon, including one for a philosopher's stone and another possibly for gunpowder.

Roger Bacon wrote on the medicine of Galen, referring to the translations of Avicenna.

Roger Bacon believed that the medicine of Galen belonged to an ancient tradition passed through Chaldeans, Greeks and Arabs.

The importance of Hermetic philosophy in Roger Bacon's work is evident through his citations of classic Hermetic literature such as the Corpus Hermeticum.

However, this is somewhat paradoxical as what Roger Bacon was specifically trying to prove in the Opus Majus and subsequent works, was that spirituality and science were the same entity.

Roger Bacon believed that by using science, certain aspects of spirituality such as the attainment of "Sapientia" or "Divine Wisdom" could be logically explained using tangible evidence.

Roger Bacon placed considerable emphasis on alchemy and even went so far as to state that alchemy was the most important science.

The reason why Roger Bacon kept the topic of alchemy vague for the most part, is due to the need for secrecy about esoteric topics in England at the time as well as his dedication to remaining in line with the alchemical tradition of speaking in symbols and metaphors.

Roger Bacon is less interested in a full practical mastery of the other languages than on a theoretical understanding of their grammatical rules, ensuring that a Latin reader will not misunderstand passages' original meaning.

Roger Bacon was partially responsible for the addition of optics to the medieval university curriculum.

Greene's Roger Bacon spent seven years creating a brass head that would speak "strange and uncouth aphorisms" to enable him to encircle Britain with a wall of brass that would make it impossible to conquer.

Roger Bacon had praised a "self-activated working model of the heavens" as "the greatest of all things which have been devised".

In particular, Roger Bacon often mentioned his debt to the work of Robert Grosseteste: his work on optics and the calendar followed Grosseteste's lead, as did his idea that inductively-derived conclusions should be submitted for verification through experimental testing.

Roger Bacon is seen as part of his age: a leading figure in the beginnings of the medieval universities at Paris and Oxford but one joined in the development of the philosophy of science by Robert Grosseteste, William of Auvergne, Henry of Ghent, Albert Magnus, Thomas Aquinas, John Duns Scotus, and William of Ockham.

Roger Bacon was not a modern, out of step with his age, or a harbinger of things to come, but a brilliant, combative, and somewhat eccentric schoolman of the thirteenth century, endeavoring to take advantage of the new learning just becoming available while remaining true to traditional notions.

Roger Bacon's was a plea for reform addressed to the supreme spiritual head of the Christian faith, written against a background of apocalyptic expectation and informed by the driving concerns of the friars.

In Oxford lore, Roger Bacon is credited as the namesake of Folly Bridge for having been placed under house arrest nearby.

Roger Bacon is honoured at Oxford by a plaque affixed to the wall of the new Westgate shopping centre.

Roger Bacon serves as a mentor to the protagonists of Thomas Costain's 1945 The Black Rose, and Umberto Eco's 1980 The Name of the Rose.

Roger Bacon appears in Rudyard Kipling's 1926 story 'The Eye of Allah'.